Why can’t we all just get along?” asked Rodney King famously, echoing the sentiments of many of us who have at some point or another wondered about the seeming intractability of human conflict. While issues of race, ethnicity, religion, class, sexual orientation, and gender can lead to strife at home, in the community, and on a national and global scale, thankfully we most often find ways to navigate and negotiate through these otherwise daunting differences.

In our organizations too, although we sometimes disagree with our coworkers based on our different roles, perspectives, or styles, we generally reach mutually agreeable and often creative resolutions without coming to literal or figurative blows. We don’t always do so fully or based on a deep understanding of the complexities involved. Neither do we always arrive at agreements that are entirely satisfying to both parties. Nevertheless, daily life would be intolerable and our organizations would grind to a halt if we were unable to compromise well enough to coexist with each other in a state of relative tolerance and truce.

A World of Contradictions

It is usually a mark of social maturity (and not inconsiderable relief) when we can find ways to live and work with each other despite our differences. Sometimes, though, one of the parties may choose to steer clear of those they are in conflict with (avoid the person), circumvent the difficult circumstances (avoid the conflict), or just take themselves out of the situation by moving on (change their environment through flight). This can happen because of imbalances of power between the parties, insufficient communication or conflict-resolution skills, or a lack of incentive for or investment in continuing the relationship.

“Why can’t we all just get along?” asked Rodney King famously, echoing the sentiments of many of us who have at some point or another wondered about the seeming intractability of human conflict.

When employees find a work situation unbearable, they can almost always change their environment and leave for greener pastures. In the days when the economy was booming and opportunities seemed unlimited, unhappy employees merely called a headhunter, sent out a dozen resumes, and were soon swamped with job offers. Employers, on the other hand, found themselves in the position of needing to offer stock options, casual Fridays, flextime, daycare facilities, foosball, and other company perks to attract and retain the best-skilled workers in the market.

Today, while the economy is looking far better than it has in the past couple of years, the employment market is, particularly in some industries, still very tight. In an uncertain economy or an exceptionally tight job market, when good, well-paying jobs are at a premium, even if an individual wishes to flee a challenging work situation, he or she may find it difficult to do so. Beyond a weak economy there may be many other reasons why employees may be forced to stay in jobs that they are unhappy in. They may do so because of health issues, the diminishing market for their specific skills, or a desire not to disrupt their family stability. Disgruntled workers may also stay where they are to protect their pensions or simply because they are unmotivated or lack the confidence to start afresh in a new environment.

Whatever their particular circumstances, in my work as a conflict resolution professional, I sometimes come across individuals who are unhappy in their present jobs as well as people who see themselves as “a bad fit,” philosophically and operationally, with their organizations or their coworkers. As a result, they can’t maintain their customary level of performance and feel demoralized. Disaffected workers in this situation end up living in a world of contradictions, at once fearful of losing their jobs because of sub-par performance, yet dreading going into the office each day. Managers on the other hand, while sensing dissatisfaction and affected by a loss of morale in their teams, are not always able to fire employees who, while evidently unhappy, are still productive.

The costs involved in replacing employees, the possibility of wrongful termination and discrimination suits, and the fear of stoking further dissent in the teams discourages them from ending the relationship.

The impact of this dynamic on the organization is considerable. When disgruntled employees stay for want of other viable options, they are often unable or unwilling to pull their weight. This behavior in turn diminishes organizational morale, because others become resentful at having to pick up the slack. Communication is affected across the board as unhappy employees become sullen and uncooperative. Teamwork suffers because of the forming of cliques and the creating of “in” and “out” groups. If management doesn’t address the problem, dissatisfaction can spread to other employees, productivity and performance may soon be compromised, and, in extreme cases, the company’s survival could be at stake (see “Growing Worker Dissatisfaction”). Again, even as these employees hang in during the tough economic times, as soon as the economy and the job market improve, they are generally out the door like a shot.

From Collaborator to Contrarian

Take the case of Nancy Miller*. When she took the position of vice president of marketing at New England Computers Inc. (NECI) in March 2001, she was confident that her career was on the upswing. For the first year or so, the challenges of the new job and the prospects of making her mark in the company brought out the best in her. By the middle of 2002, however, things had changed. NECI merged with a larger company operating out of Texas, becoming Nexus Telecom Inc. A new president replaced the one who had hired her, bringing a completely different style to the organization. Then the economic downturn and the bankruptcies of two of the company’s best customers put immense pressure on the marketing team.

While Nancy and Billy Wayne, the new president, shared a common interest in the profitability and growth of the company, their approaches to marketing seemed remarkably different. Also, whereas Nancy once had the president’s ear, she now had to go through Wayne’s executive assistant, Sandra, a brilliant young Ivy-league MBA who was evidently being groomed for bigger things. In the beginning, Nancy had tried to be friendly and welcoming to Sandra, but over time it became clear that they didn’t have much in common. The loss of access to the president, the frustration at not being able to guide the marketing direction of the company, and the increasing sense that she was being marginalized contributed to Nancy’s assessment that perhaps the time had come for her to change jobs.

Nevertheless, after a couple of months of casual networking and many discreet inquiries, Nancy found that there were few jobs on the market. At networking events, she kept running into former colleagues, now unemployed, who had been unable to find comparable positions for more than six months. Nancy’s husband and friends advised her to wait until the economy improved before making a change. Unable to move to a job that would better suit her needs, skills, and style, she remained frustrated.

Thus Nancy, who prided herself on being collaborative and a “people” person and who prized a positive attitude above all else, found herself increasingly unhappy and dreading the thought of going into work each day. Being a consummate professional, she tried to hide her feelings and function in a reasonably civil manner with her colleagues. However, her heart was not in the job anymore, and her frustrations came out in small ways. Her relations with the president’s assistant became cold and veered toward hostility. With the president, whom she had difficulty trusting, she became even more detached.

Even with her own colleagues in marketing, Nancy was unable to summon the kind of passion and humor that she brought to all her previous positions. She became less forgiving of minor administrative infractions, easily upset when things didn’t go according to plan, nervous about closing deals, and paranoid about losing her remaining accounts. She took to speaking disparagingly to her friends outside the company about the “boys from Texas.” Soon her negativity and frustration found expression with some of her staff and especially her friends in human resources, some of whom, like her, were less than enamored about the changes that came with the merger.

GROWING WORKER DISSATISFACTION

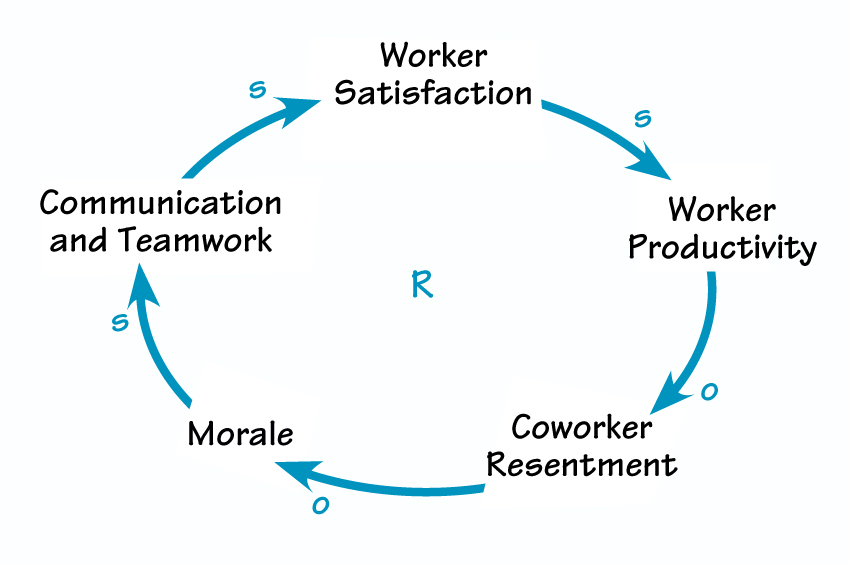

When disgruntled employees stay for want of other viable options, they often set off a vicious cycle of growing discontent in the organization. If management doesn’t address the problem, dissatisfaction can spread to other employees, productivity and performance may soon be compromised, and, in extreme cases, the company’s survival could be at stake.

In a matter of a couple of short months, the atmosphere in the organization, especially on the fifth floor where the marketing department shared space with the president’s staff and human resources, had become unbearably toxic. Cliques formed where there once had been a general sense of camaraderie; morale plummeted in the face of gossip; and productivity slipped as working groups and individuals became less forthcoming with information and pursued different and often competing agendas.

What can the company do at this point? Firing Nancy would be difficult, because she continues to be productive and meet her targets. Also, this kind of staff change would likely increase workers’ feelings of insecurity and contribute to distrust of the new leadership. In any case, although Nancy is near the eye of the conflict, she probably is not the problem herself. The issue of employee dissatisfaction and breakdown of communication is widespread and systemic within the merged organization.

Creating Trust and Open Communication

To begin to address this kind of growing crisis, top managers must first try to understand where some of the conflicts are coming from and to reestablish healthy and useful communication horizontally and vertically within the organization. By doing so, the organization can work toward a common vision with a sense of purpose, building trust and team spirit between the staff and management and across divisions and departments.

This can seem like a chicken-and-egg situation, since honest and open communication requires an environment of trust, while some will have difficulty trusting until the other party has demonstrated their ability to communicate honestly and openly. The manager, under these circumstances, needs to put in place confidence-building measures to improve communication, review existing mechanisms for dealing with grievances, and make whatever changes are necessary to create a better climate within the organization.

Regardless of whether this process is done internally or through the services of an external consultant, the inquiry needs to focus on the reasons for the disaffection and the possible differences in goals that may have evolved between employer and employee. Once both parties recognize where the disagreements are, if any, they need to be able to navigate and negotiate through them, bearing in mind the larger goals and mission of the organization. During this process, the facilitator can help participants find ways to hear and meet the legitimate needs of the other party, while ensuring that their own needs and those of the organizations are honored.

After the initial anxieties that are brought to the fore by the shock of honest expression are resolved, this process can create a powerful and open climate where people are listened to and feel understood, and can strive to achieve common goals. Another important benefit of this approach is the creation of a more relaxed and trusting work atmosphere and the building of stronger organizational loyalties. In some situations in which the divide between individual and organizational goals proves insurmountable, management will have to move that person to a more appropriate job within the organization or assist him or her in transitioning out.

When an organization invests in this process, it demonstrates its responsible, caring, and humane side. Employees reciprocate by feeling happier, more secure, and more cooperative than before.

It is useful to think of conflict as an early warning sign that tells of an impending disconnect between the systems that we have in place and the changing circumstances.

Listed below are some specific steps that managers can take to address the issue either through marshaling its own internal resources or by calling in an outside consultant. These can be divided into “Problem Specific” actions, which address immediate needs and concerns, and “Systemic” actions, which focus on developing long-term solutions.

Problem-Specific Approaches

1. Communicating: The first thing a manager can do is to initiate a private conversation with the employee with a view to listening carefully, without judgment, to his or her complaints.

2. Understanding the Other’s Interests: The manager needs to understand the employee’s basic interests (needs, desires, and concerns), differentiating these from positions he or she may be taking from a place of fear or frustration.

3. Articulating One’s Own Interests: After having clearly understood where the employee is coming from, the manager can try to make clear his or her own basic interests and those of the organization.

4. Appreciating Similarities and Differences: Once both parties understand each other’s interests, they have a better handle on where the differences exist and on the true nature of the conflict.

5. Negotiating: The manager can now try to meet some of the employee’s genuine needs. This might require some creative problem solving (increasing the size of the pie!) as well as negotiation.

6. Agreeing: This conversation might result in agreements that include accommodations and compromises that both parties can live with.

7. Maintaining the Relationship: Once the negotiation is complete and agreements have been made, periodic check-ins are necessary to ensure that the agreements are working and the lines of communication remain open.

Systemic Approaches

1. Assessing the Conflict: Management (either internally or by bringing in a consultant) needs to assess the organizational climate and study the nature and source of the conflicts within the organization.

2. Designing an Intervention: Based on the findings in the assessment phase, a team makes recommendations for strategies or interventions to be implemented.

3. Training and Education: It is possible that the first intervention may be to offer a communication and conflict-resolution training program for all employees to help develop some organization-wide capacity in this arena.

4. Mediating: Managers who have significant interpersonal issues to deal with could be offered an opportunity to meet with a mediator.

5. Revisiting the Mission and Vision: In some cases, it might be necessary to reexamine the corporate vision and mission in light of the changed internal and external circumstances, the needs and goals of the larger organization, and those of the individual employees.

6. Designing Procedures and Protocols: Organizations need to design and put in place a conflict-response and management system, such as sophisticated grievance procedures and reporting protocols, that gives the organization the tools and mechanisms to deal with disputes and conflicts when they arise.

7. Institutionalizing an Ombudsman: The organization may find it useful to appoint from within or hire an ombudsman who can objectively weigh in on contentious issues.

8. Coaching: The organization can also ensure that all senior managers, especially those in leadership positions, have access to individualized executive coaching services to enable them to function at optimum levels.

Organizations may, depending on the context and their specific needs, build into their system some or all of these mechanisms and procedures. Beyond the challenges of dealing with unhappy employees who won’t leave and whom you cannot or choose not to terminate, this approach also has broad applicability in most any interpersonal conflict that occurs in the workplace.

Creative Opportunities in Limited Choice

Immigrants whose right to live in this country is tied to their job have long experienced the challenges of not being able to leave a difficult work situation. Because of the many restrictions inherent in the employment visa, newcomers who come to the United States on an employer-sponsored work permit (such as the H1B visa) often have less flexibility than their colleagues who are citizens or permanent residents. Changing jobs for them entails not just getting a job offer, but the legal hassles and the expense of switching sponsorship from one employee to another.

Some of the frustrations that these workers experience are similar to Nancy’s; however, they are exacerbated by the additional insecurity of being at risk of having to leave the country should they lose their job. Sometimes, though, such situations can present creative opportunities that, strangely enough, come from having limited choice.

In one case, a new immigrant, Rathin, had major conflicts with his supervisor, John. He was so miserable that he considered quitting his job. However he knew that were he to leave the job, he would most likely have to leave the country too, having been sponsored for employment by his company. Not willing to completely disrupt his life, Rathin was forced to adopt innovative ways in which to rebuild his relationship with John, something he might not have tried were he able to easily move on to another job. He decided to ask for an opportunity to go in for mediation with John.

The company agreed to the expense, and both John and Rathin met with a mediator for a couple of sessions. As a result, both employee and manager gained a better understanding of where each of them was coming from, each other’s needs, and the possible causes for frustration.

They were able to communicate better with each other, and they became more sophisticated in dealing with difficult and potentially contentious matters. They were also able to resolve many of the tensions that had prevented them from working well together. Rathin and John now have worked their way to a good professional relationship, and Rathin enjoys his job tremendously.

In this context, conflict is not something to be avoided; it is simply a sign of problems within the organization. In our increasingly complex and ever-shifting world, it is useful to think of conflict as an early warning sign that tells of an impending disconnect between the systems that we have in place and the changing circumstances. It can also tell us of the possible need to reexamine our own philosophies, assumptions, and biases, however well they may have served us in the past.

While conflicts often cause discomfort, are unpleasant, and illuminate the cracks in the system, they also present opportunities for deeper learning, growth, and meaningful change, if we address them creatively and with skill. Today these skills are available to organizations in the shape of a wealth of research, knowledge, and literature on the subject and through access to professionals who have been trained to help individuals and organizations deal with conflict.

Ashok Panikkar (apanikkar@vantagepartners.com) is a communication and conflict-resolution professional. He is presently employed at Vantage Partners, a management consulting firm specializing in building both organizational and individual expertise in negotiations and managing critical relationships.

NEXT STEPS

- Employee dissatisfaction often festers and remains hidden because people don’t feel comfortable openly raising their concerns with their managers. As a first step to ensuring that these conversations can happen, evaluate the levels of trust and open communication in your organization. Ways for conducting the assessment include anonymous employee surveys, interviews with a neutral (often outside) party, or careful observation of the dynamics that take place in group settings, such as meetings.

- If levels of trust are low, plan a strategy for creating a more open, more trusting culture. The steps listed in “Systemic Approaches” on pages 4 and 5 are a good place to start.

- Even if levels of trust are high, create a forum in which employees can regularly express their concerns and observations. These shouldn’t be “complaint sessions” but rather a place for constructive conversation to take place. Tools such as the “Ladder of Inference,” “Lefthand/Righthand Column,” and “Advocacy and Inquiry” can be useful (for resources on these and other tools, go to www.pegasuscom.com, look in the column on the left, and click on “Conflict Management”).