Imagine getting a knock at the door from a social worker telling you that you’re being investigated for abusing your child, and at the same time being asked to partner with the social service agency to ensure your child’s safety in your home. “It’s no surprise that right off the bat we get an adversarial reaction from the parent,” says Lewis H. (Harry) Spence, commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Social Services (DSS). “One of the deepest wounds any adult can experience is around their parenting capacity. Yet our social workers have to inflict this wound every day in order to help families keep their children safe.”

Since his appointment in November 2001, Spence has been thinking deeply about the paradoxical nature of the child welfare system. Chosen for his long and impressive record of advocating for children and families, providing fiscal stewardship, and understanding complex systems, he says that one of the first things he initiated for himself was “an analysis of the coherence among the organization’s values, structure, process, praxis, and content.” In the course of his analysis, Spence came upon studies that showed that the gap in child welfare agencies between espoused theory and theory in practice is as great as any recorded in organizations that have been studied.

He attributes this gap in part to the enormous stress the child welfare system is under at any given time— particularly the stress that frontline workers face by constantly having to make life and death decisions with little real support from their own organizational culture or the culture at large. People don’t automatically consider child welfare in the same category of heroic public service as police and fire departments. And, unlike those institutions, when something goes wrong, such as when a child dies, the public immediately blames DSS.

Aligned Values

People don’t automatically consider child welfare in the same category of heroic public service as police and fire departments. And, unlike those institutions, when something goes wrong, such as when a child dies, the public immediately blames DSS.

One of the first steps Spence and his staff took to close the gap was to draft six clear, aligned statements that help people understand and agree on what constitutes good work. They have called these statements “practice values” for the agency’s work: it is child-driven, family-centered, strength-based, community-focused, committed to diversity and cultural competence, and committed to continuous learning. “These values are not radical in the child welfare world,” says Harry. “What would be radical is actually figuring out how to achieve them, which is what we’re trying to do.”

After they drafted the value statements, he and his staff set about building consensus around and commitment to achieving them at every level of the organization. First, they met with senior managers in Boston to revise and hone them; then they took the discussion to all senior managers throughout the state. Next they conducted their first statewide DSS leadership conference to include parent and family representatives, many of whom had been found to place their children at risk through abuse and neglect, in the conversation. Now DSS is planning to hold discussions at the local level. The reason for developing the value statements in a collaborative way — that is, in dialogue with DSS leaders and client representatives — is to link the value statements powerfully to daily practice.

Another step has been to recognize and make explicit the three levels of child welfare practice: clinical (the frontline social workers working with particular families), managerial (the management system that oversees, guides, supports, evaluates, and organizes the work of those social workers), and system of care (the organization’s partnership with other public services such as mental health systems, school systems, and private providers, including foster families and adoptive parents). Spence asserts, “To create coherence among these three, we need to drive the same agenda at each level and constantly maintain awareness of how they work together and reinforce one another. Otherwise, signals and incentives to everyone in the system become confused.”

Quality Improvement

Simultaneously, Harry has been working to implement quality improvement systems. He observes, “The big challenge here is that child welfare involves immense discretion all the time. I learned early in my life that no matter how many bureaucratic categories you create, the next case you take up will immediately confound those categories. The varieties of human misery are simply too complex to be captured in 10, 100, or 1,000 boxes.”

Acknowledging that regulation does play a foundational role in setting minimum standards, the commissioner believes that to truly succeed, the real work has to go beyond regulation. He fosters excellence by advocating for a mutual accountability system, which he defines as the responsibility each of us has to help others above and below us in the organization to do their very best work. He’s also careful not to impose solutions that worked elsewhere. “While certain things we learn about organizations and their management are transferable,” he explains, “this learning is only of value to the new organization you enter if it’s linked to a deep and profound regard for the craft of that organization. Otherwise, the systems you put in place can be powerfully destructive.”

One system in the queue for improvement is the current individual accountability model for social workers, which Spence believes runs counter to DSS practice values. After observing the disparity between the level of support that social workers need to do their jobs and the actual support they get, he initiated research into moving toward a team-based accountability system. In the process, he discovered that every state in the country works on the solo practitioner model, in which single social workers are responsible for an enormous number of children. These caseloads range from 11 cases per day in New York to 18 cases in Massachusetts to roughly 35 cases in Florida. Interestingly, the teams that do appear in child welfare are “expert” teams, composed of child psychiatrists, pediatricians, lawyers, and other specialists. The results of this research prompted DSS to apply for a substantial grant from a foundation (which they recently received) to develop and test a team-based model for social workers.

“To realize continuous improvement, we have to be able to identify, safely acknowledge, and learn from error as quickly as possible, and then build systems to insulate against the damaging consequences of inevitable mistakes while reducing the frequency of those mistakes.”

—Lewis H. (Harry) Spence

What the commissioner considers the linchpin of the child welfare accountability problem, however, is public pressure. He notes that, in general, child welfare appears on our radar screen when we read about the death of a child in DSS custody. The public then puts pressure on the agency to fire the “guilty” social worker so we can assure ourselves that we’re not culpable for that death. “Within child welfare, that is an experience of deep betrayal,” Spence says. “What yesterday was perfectly acceptable work today becomes grounds for firing because suddenly the boss, to remove himself from the public spotlight, needs to find someone to take responsibility for the death of the child. He usually turns a perfectly innocent party into a sacrificial lamb.”

Rather than ruthlessly penalize individuals, Spence wants the community to hold DSS accountable for instituting strong learning systems, similar to what the healthcare system has been developing in the last few years around fatalities in hospitals. “To realize continuous improvement,” he says, “we have to be able to identify, safely acknowledge, and learn from error as quickly as possible, and then build systems to insulate against the damaging consequences of inevitable mistakes while reducing the frequency of those mistakes. We cannot accomplish this by constantly punishing ordinary human error. Certainly, there need to be consequences for negligence or dereliction of duty, but if I were held to an error-free standard, I wouldn’t survive a single day of work here, nor would anyone else.”

In the face of these long-standing challenges, Harry knows he cannot expect his staff to immediately trust the new systems he’s striving to put in place. Instead, he asks them to maintain a healthy skepticism while he tries to give voice to their hope of making a real difference in child welfare. He says, “We all struggle with questions such as, ‘Do I act on the thing that first brought me here—a genuine desire to help parents and families?’ or ‘Do I drive my practice on what I know about the punitive accountability system — the risk of being publicly flayed alive?’ All I’ve tried to do is operationalize the part that says, ‘I came here to deeply care for children and families.’”

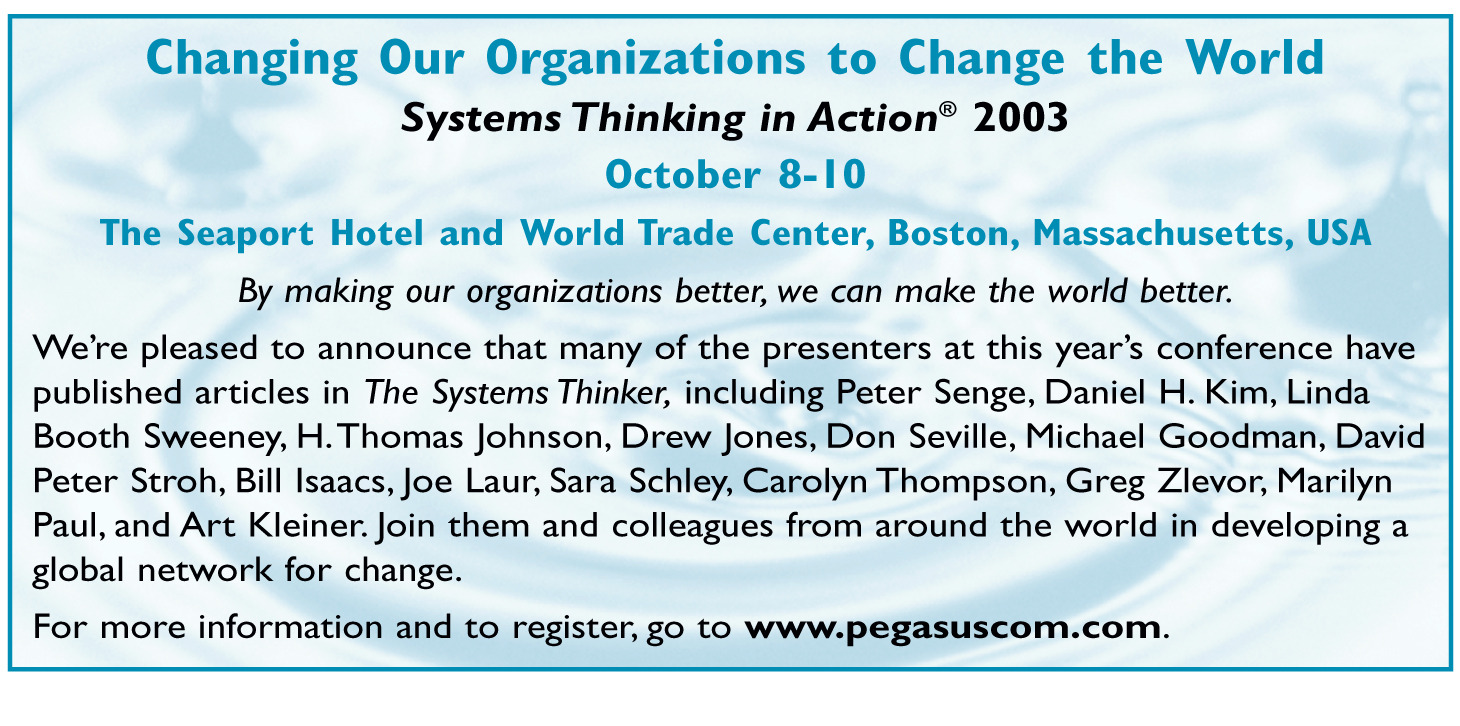

Kali Saposnick is publications editor at Pegasus Communications. Harry Spence will be a keynote speaker and session presenter at this year’s 2003 Pegasus Conference in October, where he will share the learnings that he acquired at DSS as well as in his previous positions as deputy chancellor for operations for the New York City Public Schools; governor-appointed receiver for the bankrupt city of Chelsea, Massachusetts; and court-appointed receiver of the Boston Housing Authority.