The lessons we learn by studying the “Fixes That Fail” and “Shifting the Burden” archetypes revolve around the kinds of actions that we choose to take and the consequences of those actions over the long term. In “Escalation,” the situation becomes more complex, because our actions directly affect the actions that others take. But unlike what we learned in physics—where every action produces an equal and opposite reaction—our actions are amplified with each round, leading to a phenomenon known as escalation. If left unchecked, the escalation dynamic can spiral out of control, going far beyond what either side may have intended.

The Eye of the Beholder

In the U. S., the expression “keeping up with the Joneses” describes the rivalry that some homeowners fall into with their neighbors. So, if the Joneses buy a new car, the Smiths feel compelled to replace their old vehicle with the latest model. When the Joneses have their yard landscaped, the Smiths do the same. And on it goes.

In this case, escalation occurs when we equate acquiring material things with success. Once we become involved in a competition- whether it’s over which neighbor has a neater lawn or which airline is the lowest fares—we unconsciously raise the ante with each additional action that we take. For example, even though the Smiths believe they are merely “keeping up” when they buy their new car, they may choose one with bells and whistles that the Joneses’ car doesn’t have, triggering another round of escalating conspicuous consumption.

Because parity is in the eye of the be holder, escalation dynamics can erupt in any relationship that involves even the slightest hint of rivalry. On the playground, we have all seen how an accidental bump quickly escalates into a shoving match and then into an all-out fight. On a larger scale, we have lived through perhaps the largest escalation dynamic in human history—the nuclear arms race between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Innocuous Beginnings, Destructive Endings

Why does escalation often spin out of control? One reason is that delays contribute to distortions in the information flowing between the two sides. One delay occurs between the actions that each party takes and the results of those actions. The other is between the relative position of each participant vis-à-vis the other and the perceived threat that this positioning causes the parties to feel. Information gets distorted along every link in the system; however, the second delay may have the greatest effect, in that it leads each side to overestimate the impact of its rivals’ activities on their relative position.

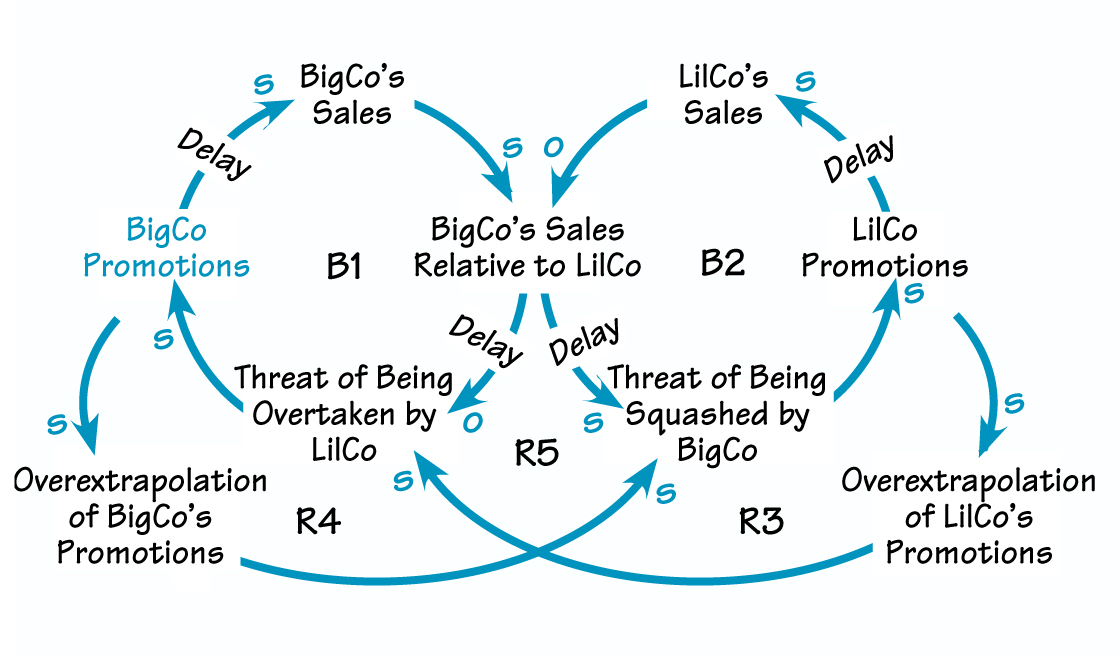

THE STRUCTURE OF ESCALATION DYNAMICS

When BigCo increases its promotions (B1), it takes time for the effects to show up. Thus, LilCo does not feel threatened initially. When LilCo finally realizes that it has fallen behind, it tries to catch up (B2). BigCo feel threatened by these aggressive actions and over extrapolates the impact of LilCo’s promotions (R3). In turn, LilCo sees BigCo’s efforts as an even worse threat and again increases its own promotional activity (R4).

Thus, when BigCo increases its level of promotions, the results of these activities do not show up immediately in higher sales (B1 in “The Structure of Escalation Dynamics”). For this reason, BigCo may engage in more promotions than it originally intended; for instance, by prolonging a special offer. This delay contributes to the escalation dynamics, because LilCo then perceives BigCo as aggressively promoting its products. In the short-term, LilCo may respond by engaging in simple “Tit-for-Tat” behavior (see “Three Regions of Escalation”).

Eventually, the results of BigCo’s actions do become visible (B2). But, because of the delay between relative results and feelings of being threatened, LilCo remains complacent about its level of activity relative to BigCo. When LilCo finally realizes that it has fallen behind, the gap between BigCo’s sales and LilCo’s sales is wider than it might have been if LilCo had seen the relative impact of BigCo’s actions sooner. When LilCo takes action, it does so from a heightened state of threat and tries to catch up to BigCo as fast as it can. BigCo then interprets this increased level of activity as an attempt by LilCo to raise the stakes. So, BigCo now over-extrapolates LilCo’s catch-up activity as a threat to its own position and, in turn, increases its activities (R4). LilCo sees BigCo’s increased market- ing efforts as an even worse threat and again increases its own promotional activity (R3). Both sides are fast approaching the turbo-charged region of All-Out Escalation.

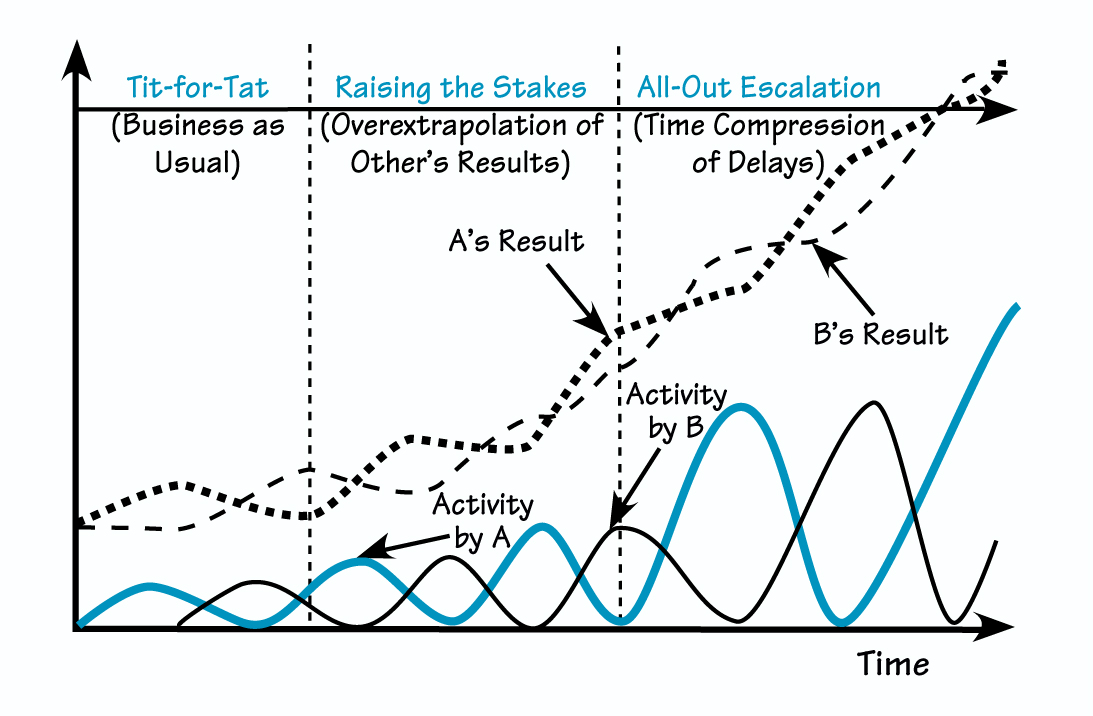

THREE REGIONS OF ESCALATION

In the early stage of “Escalation,” the parties engage in “Tit-for-Tat” behavior. As each company over-extrapolates the other’s activities, they “Raise the Stakes” with each action. When the rivals reach “All- Out Escalation,” they act with ever-increasing speed and volatility until something devastating happens.

In All-Out Escalation, time delays become compressed. Because the par- ties have previously been caught off- guard as a result of delays, neither side wants to wait for additional results to materialize before taking action. The problem is that those sub- sequent actions are based on each party’s extrapolations—usually inflated—of the other’s activities (R5). When escalation reaches this level, activity by one party begets more activity by the other with ever- increasing speed and volatility until something devastating happens.

In the case of BigCo and LilCo, it may appear that there is nothing wrong because sales continue to rise for both companies. However, pro- motional costs are rising faster than sales, so margins are shrinking even while sales are growing. Companies have engaged in these kinds of dynamics to the point where they sell their products at a loss because they are so focused on not being “outsold” by their competition!

Early Warning Systems

Escalation dynamics can occur in numerous business settings, such as price-cutting wars, promotional competitions, and product-feature battles. So, how can you keep from getting lured into these dynamics in the first place?

As with almost all conflicts, the best time to deal with escalation is early in the process, before the dynamics take on a life of their own. For the “Escalation” archetype, this means paying attention to the interplay between you and your rival while you are still in the relatively harmless Tit-for-Tat stage. Take the first rumblings of an escalation dynamic as your early warning to proceed with caution. Immediately assess the value proposition that you are offering your customers. For instance, when a competitor begins to target your customers by emphasizing a lower price, it is easy to respond by lowering your price as well. But perhaps your competitor picked price as the variable because that is the only thing that they can compete on.

The problem with responding in kind to this gambit is that you allow your competitor to set the ground rules. This proved to be a costly mis- take for Texas Instruments, when it allowed Commodore to choose price as the competing variable for the home computer. Instead of emphasizing the superiority of its product, Texas Instruments lowered its prices. Price cuts followed price cuts until TI ultimately admitted defeat, writing off the TI 99/4A computer, which cost the company hundreds of millions of dollars.

Instead of letting the competition dictate your strategy, refocus your business strategy. When FedEx was experiencing stiffer competition in the overnight delivery business and others began to lower their prices, FedEx could have joined he fray by cutting its own prices. However, it chose to emphasize a value proposition that was even more important to customers who used overnight delivery services than price: reliability. By doing so, the company reestablished its leadership role in the overnight delivery business and was able to maintain higher pricing than its competitors.

Ending the War Games

In the hit movie “War Games,” a Defense Department computer assumed control of all U. S. nuclear warheads. As the computer was in the process of cracking the security code that would allow it to launch the entire U. S. nuclear arsenal at the U. S. S. R, the programmer-hero engaged it in playing tic-tac-toe over and over again, hoping it would learn that trying to win the game was futile. In the end, the computer did learn that lesson and concluded that all thermonuclear war scenarios would lead to a no- win situation. Even though “War Games” was fictional, it accurately captured the potentially destructive quality of escalation. More individuals, companies, and countries embroiled in escalating struggles could learn a valuable lesson from understanding the pitfalls of this structure.

Daniel H. Kim, Ph. D., is publisher of The Systems Thinker and a member of the governing council of the Society for Organizational Learning.

Editorial support for this article was provided by Janice Molloy.