For 10 years now, Peter Senge’s articulation of the five disciplines of organizational learning have revolutionized the business and healthcare arenas. The practice of personal mastery, shared vision, team learning, mental models, and systems thinking (the “fifth discipline,” or cornerstone, of organizational learning) have helped organizations worldwide to improve their ability to create the future they desire.

As with any important effort, the road has been rocky. In The Dance of Change (Currency/Doubleday, 1999), a volume in the Fifth Discipline Fieldbook series, the authors address this reality head on. They explore the systemic dynamics behind common obstacles to transformative change, and offer suggestions for working with these forces instead of against them (see “Change as Challenge: Taking Stock of Organizational Learning,” THE SYSTEMS THINKERV10N2).

A New Arena

Introducing the tools and principles of organizational learning to the corporate world made perfect sense. After all, in many ways business is the most powerful institution today in many parts of the world. And as globalization proceeds apace, the need for more systemic thinking and problem solving in the world of work grows with it. Companies, cultures, and economies are so thoroughly intertwined now that businesspeople everywhere must learn to think more than ever in terms of interrelationships rather than separate entities.

But all along, these same tools and principles have had just as much relevance—if not more—for the educational arena. The obvious reason is that young people who know how to grasp and work with systemic forces will later become professionals with much needed problem-solving and management skills. By teaching systems thinking and organizational learning principles and tools to schoolchildren —the very source of future work forces—educators take a truly systemic approach to addressing many of the problems that plague the rest of society.

Bringing organizational learning into the classroom makes sense for another reason as well: Children find it much easier to think in fresh ways than adults do. Theorists cite many possible reasons for this—including social and biological explanations. The important point is that educators who introduce organizational learning into the classroom are building on young people’s existing strengths and proclivities.

The Legacy of Industrial Age Thinking

This isn’t to say that school systems have ignored the concepts behind organizational learning until now. In a number of pockets throughout the United States—including grammar schools, high schools, and business schools within colleges and universities—students, teachers, and administrators have been familiarizing themselves with computer simulation models, causal loop and stock and flow diagrams, behavior over time graphs, mental models, and other tools and disciplines from this field.

However, many of these pioneers have had to struggle forward in relative isolation. The educational arena is notoriously slow in embracing change. Some teachers who have introduced organizational learning in the classroom have faced the same resistance to new ways of thinking that their counterparts in the business world have encountered.

With Schools That Learn: A Fifth Discipline Fieldbook for Educators, Parents, and Everyone Who Cares About Education (Currency/Doubleday, 2000), Peter Senge et al. offer a new resource designed to support and encourage educational pioneers. Like earlier volumes in the Fifth Discipline Fieldbook series, the book starts off by establishing the context in which to understand current challenges. In an essay early in the book, Senge shows how Industrial Age principles have led to “assembly-line” schools. Specifically, mechanistic concepts like standardization and command-and control leadership, along with isolation of schools away from larger society, “have created many of the most intractable problems with which students, teachers, and parents struggle to this day.”

As Senge explains, machine-age thinking in the classroom has “operationally defined smart kids and dumb kids. Those who did not learn at the speed of the assembly line either fell off or were forced . . . to keep pace.” Moreover, Industrial Age thinking assumes that all children learn in the same way. Educators have become controllers and inspectors, rather than mentors, and learning has become teacher-centered rather than student-centered. (That is, teachers—not young people themselves—are responsible for generating motivation in the classroom.)

A Learning System

But the coauthors of Schools That Learn contrast this troubling picture with a strikingly different one: classrooms that embrace children’s diverse learning styles; that engage students’ minds, hearts, and bodies; that show kids how what they learn in school has relevance to the world around them; and that acknowledge and support forms of intelligence beyond traditional “book learning.” In short, these authors offer a vision of schools in which educators assume not only that all children can learn, but that they want to learn.

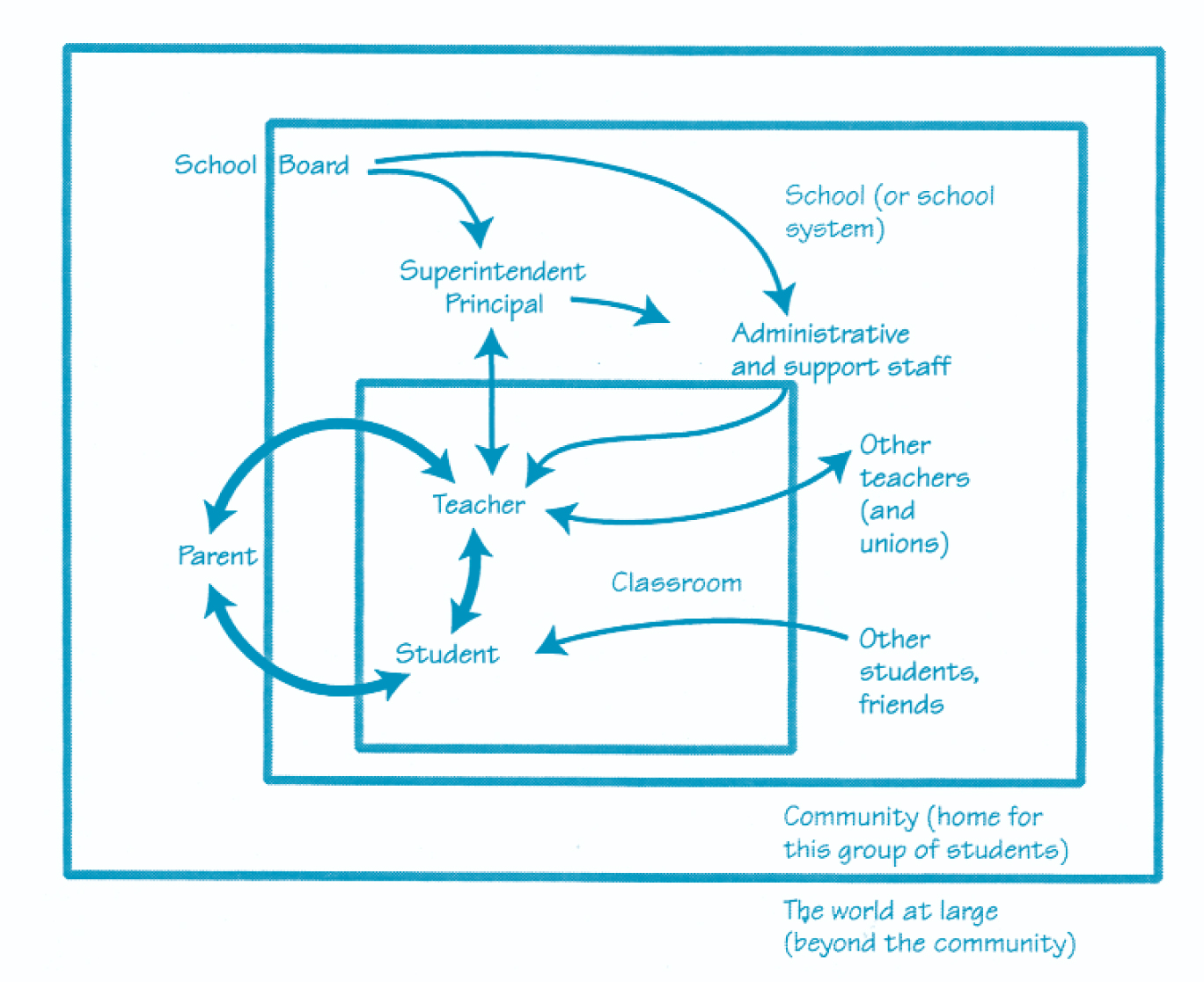

Moreover, the authors paint a picture of a learning system (see “The Learning System”). In this system, teachers, students, parents, principals and superintendents, school boards, neighborhoods, and administrative and support staff all mutually influence one another in ways that support the vision described above.

Learning Schools in Action

To show that this vision is possible and to describe strategies for bringing it to life, the authors have invited working teachers, theorists, and educational consultants from around the globe to contribute their ideas and stories to the book. The selections are organized into three main sections: Classroom, School, and Community. Within each section, the pieces range from practical advice on implementing change and accounts of successful innovation from actual classrooms, to personal essays about contributors’ own experiences as students, to descriptions of hands-on exercises and techniques.

In all three sections, the five disciplines of organizational learning are woven into the section themes. For example, within Classroom, education researcher Linda Booth Sweeney explains how parents and teachers can identify powerful systems thinking lessons in children’s books from around the world. In another selection, teacher and administrator (and coauthor) Tim Lucas describes tools and exercises that he uses in the classroom to encourage students to map their mental models, or their assumptions about how the world works. Within the School section, education professor and coauthor Nelda Cambron-McCabe outlines a process for clarifying education’s core purpose and defining what it means to be a school leader. And in the Community section, Tan Soon Yong describes a “learning-nation initiative” that is currently unfolding in Singapore— with striking results.

Schools That Learn as a Tool for Change

Like earlier Fifth Discipline Fieldbook volumes, Schools That Learn is not intended to be read sequentially from front cover to back cover. Instead, the authors encourage users to browse according to their interests, and to make use of the cross-references that point out meaningful links to follow. Margin icons—such as a lighthouse for “guiding idea,” a hammer and wrench for “tool kit,” and a tandem bicycle for “team exercise”—cue readers as to the nature of each selection.

THE LEARNING SYSTEM

In this learning system, each individual and organization mutually influences one another in ways that support the vision of a learning school. Source: Schools That Learn: A Fifth Discipline Fieldbook for Educators, Parents, and Everyone Who Cares About Education, by Peter M. Senge, et. al. (Currency/Doubleday, 2000), p. 15. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

The authors also offer guidelines for crafting an organizational-change strategy. For instance, they recommend introducing any change strategy on all three levels of classroom, school, and community. They also urge readers to focus on “one or two new priorities for change, not twelve,” and to involve students, parents, and educators in change efforts.

As in business and healthcare, the educational world faces a challenge in rethinking the nature of learning and in implementing change. Yet realizing the vision that Senge and his coauthors describe isn’t impossible. As Schools That Learn makes clear, some classrooms, schools, and communities are changing in a positive direction already. For those just starting out, this book offers a road map for navigating the journey.

Schools That Learn is available from Pegasus Communications at www.pegasuscom.com.

Lauren Keller Johnson is principal of Ghost in the Machine, a writing-and-editing-services company based in Lincoln, Massachusetts