Bijou Bottling Company is a fictitous beverage bottler with an all too real problem: chronic late shipments. Its customers—major chain retailers—are looking for orders shipped complete and on time. About five years ago, in a U. S. region covering about six states, this problem reached crisis proportions…

In the face of day-to-day pressures, groups often leap to solutions after only a modest amount of brainstorming. A systemic approach, however, provides a structured problem-solving process for digging deeper into our most vexing problems.

To get a sense for how systems thinking can be used for problem identification, problem solving, and solution testing, we have outlined a six-step process. To use this process on a problem in your workplace, try the worksheet on page 9.

1. Tell the Story

The starting point for a systems thinking analysis is to get your head above water enough to start thinking about the problem instead of just acting on it. An effective way to do this is to gather together all of the important players in the situation and have each one describe the problem from his or her point of view.

At Bijou Bottling Company, the problem was usually a customer complaint: “Where were the 40 cases of 2-litre Baseball tie-in product that were ordered last week?!” Somehow Bijou would get the goods there on time, whatever it took—including air shipping heavy soda in glass bottles at enormous costs. But this crisis management led to a culture where people built their careers on coming in at the 11th hour and turning around a customer complaint.

2. Draw “Behavior Over Time” Graphs

In the storytelling stage, most of the energy is focused on the pressures of the current moment. When we move to “Behavior Over Time” (BOT) graphs, however, we begin to connect the present to the past and move from seeing events to recognizing patterns over time.

Draw only one variable per graph on a Post-it™ note so it can be easily moved around in the steps that follow. The time frame should span from past up to the present—but it can also include future projections (see “Bijou Over Time”).

3. Create a Focusing Statement

At this point, you want to create a statement that will help channel energy during the rest of the process. This statement may involve a picture of what people want, or a question about why certain problems are occurring. At Bijou, for example, the focusing statement was: “We’re pretty good at solving each problem as it arises. But why are these problems recurring with greater frequency and intensity? What is causing them?”

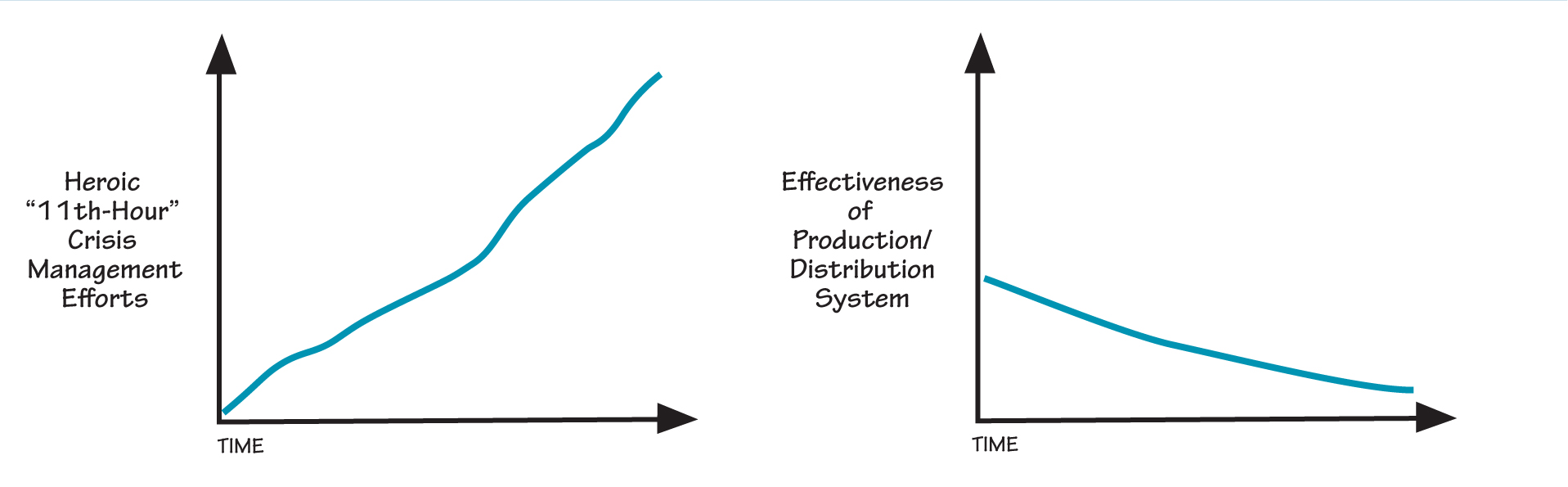

BIJOU OVER TIME

At Bijou, crisis management efforts had increased over time, while the effectiveness of the production/distribution system had decreased.

4. Identify the Structure

You now want to describe the systemic structures that are creating the behavior patterns you identified. The systems archetypes are an easy way to begin building a theory of why and how things are happening (see “Systems Archetypes at a Glance,” V22N6, August 2011).

Begin by reviewing the story, graphs, and focusing statement to see if they follow the storyline of an archetype. If so, draw the loop diagram for that archetype, place the Post-its of the variables in the diagram, and move them around on a flip chart until you have a diagram that seems to capture what is going on.

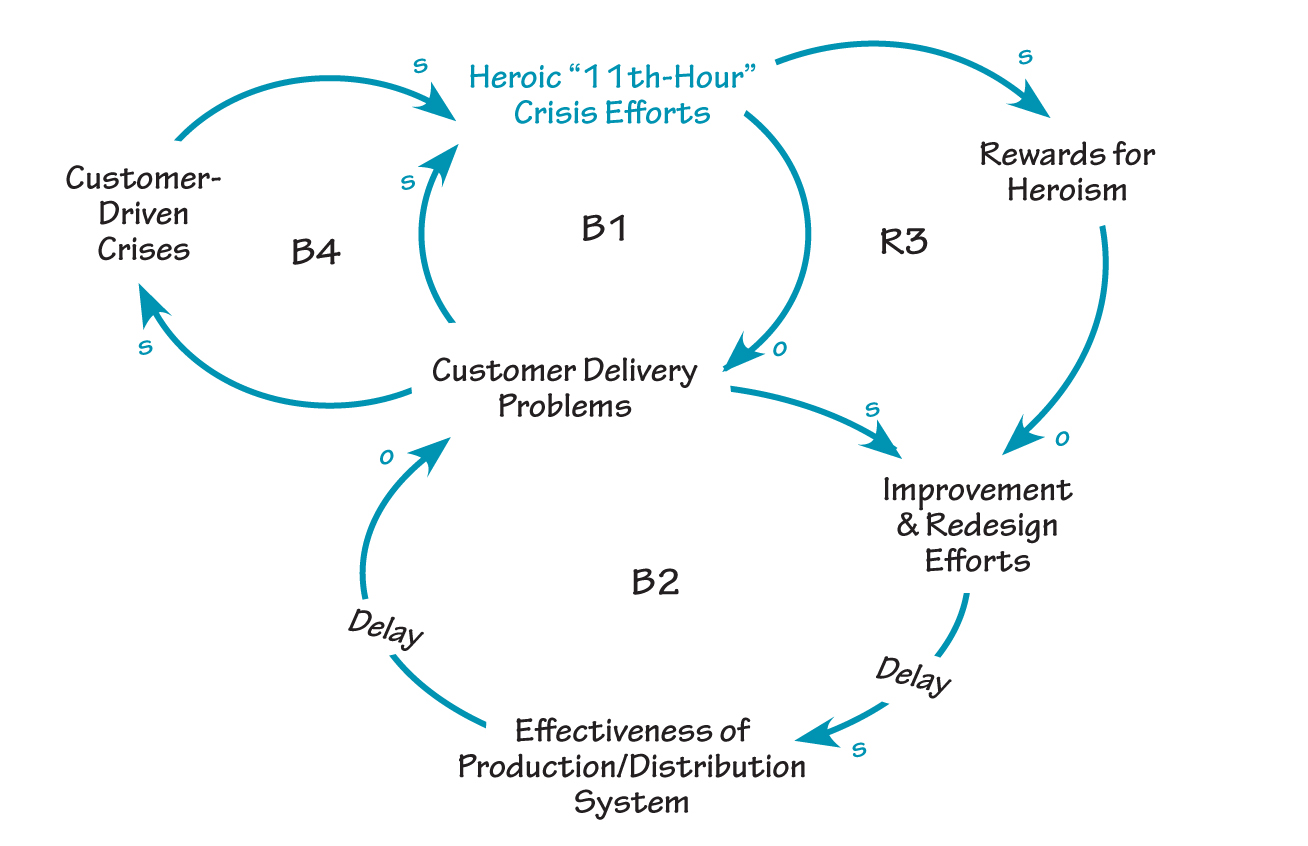

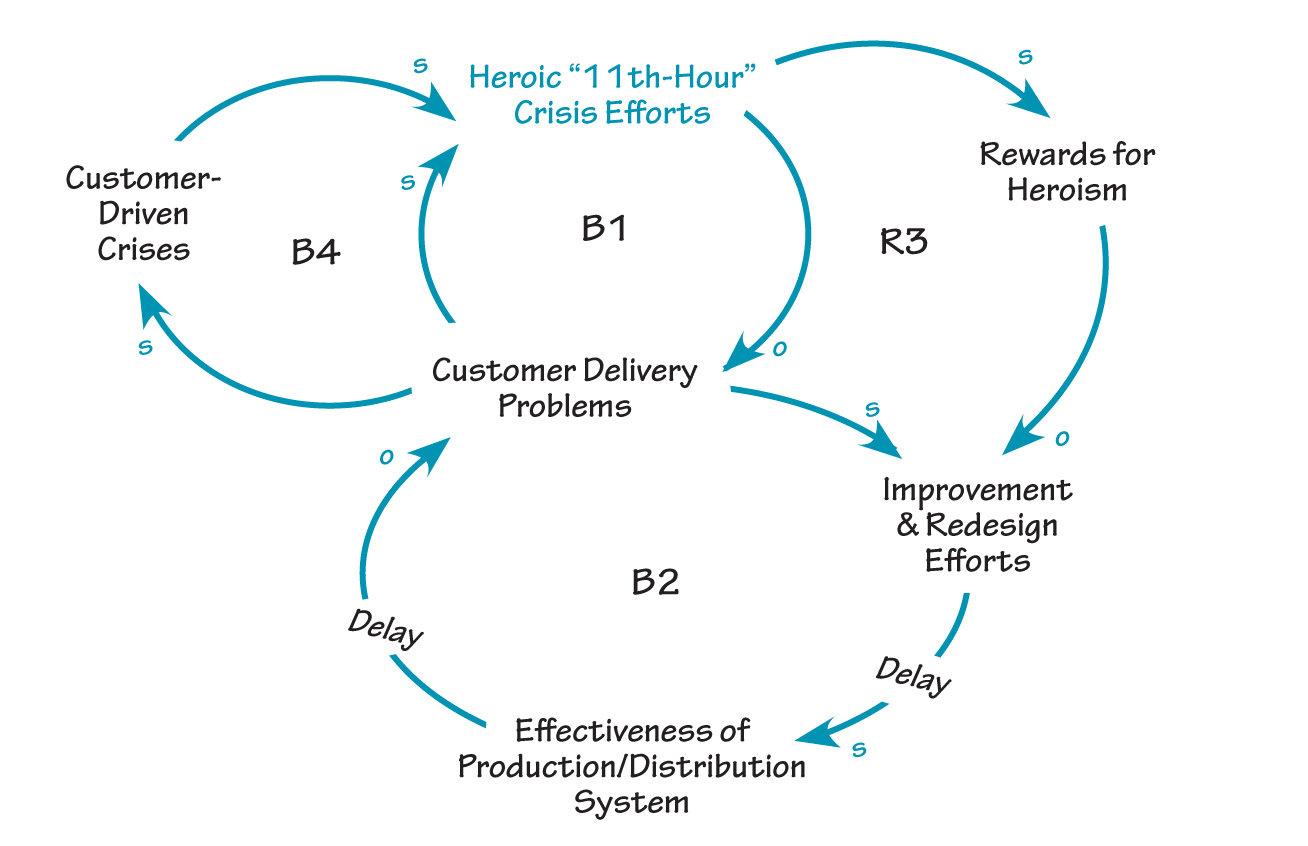

The group at Bijou decided that their problem matched the “Shifting the Burden” storyline, in which a problem is “solved” by applying a short-term solution that takes attention away from more fundamental improvements. They identified a balancing loop that described how customer problems were solved with heroic “11th-Hour” efforts (the symptomatic solution) at the expense of improvement and redesign of the production/distribution system (the fundamental solution). As people “learned” over time that heroism is rewarded, their willingness and ability to address system-wide problems decreased (see “Shifting the Burden to Heroism”).

SHIFTING THE BURDEN TO HEROISM

At Bijou, customer problems were solved with heroic “11th-Hour” efforts (B1) rather than with improvements in the production/distribution system (B2). Over time, people at Bijou “learned” that heroism is rewarded, which reduced their willingness and ability to address system-wide problems and increased the company’s dependence on heroic efforts (R3). One negative side-effect of Bijou’s “heroism” attitude was that customers were taking problem situations and escalating them to crises in order to get the company’s attention (B4).

5. Going Deeper™ into the Issues

Once you have a reasonably good theory of what is happening, it is time to take a deeper look at the underlying issues in order to move from understanding to action. There are four areas you should clarify:

- Purpose of the System. Ask yourself, “In the larger context, what do we really want here?”

- Mental Models. Begin the exploration of mental models by adding “thought bubbles” to those links in the diagram that represent choices being made (see “Mental Models and Systems Thinking: Going Deeper into Systemic Issues,” V23N5, June/July 2012).

- The Larger System. Add links and loops to enrich the story and connect the relationships to the larger system.

- Personal Role. Acknowledge and clarify your own role in the situation.

For example, when the people at Bijou looked at the larger system, they wondered what role their customers played in the system. They theorized that customers were taking problem situations and escalating them into crises in order to get the company’s attention (B4).

6. Plan an Intervention

When planning an intervention, use your knowledge of the system to design a solution that will structurally change it to produce the results you want. This might take the form of adding a new link or loop that will produce desirable behavior, breaking a link or loop that produces undesirable behavior, or a combination of the two. The most powerful interventions often involve changing the thinking of the people involved in the system.

At Bijou, the key to change was realizing that the problems were largely self-inflicted. They realized that they had to make progress on production/distribution system improvements while still doing enough fire-fighting to keep things afloat. In the longer term, they would need to change the reward systems that promoted heroic behavior. They also recognized the need to sustain the improvement efforts even when the pressure came off—otherwise the problems would be back again soon.

Part of a Cycle

Even as systems thinkers, it is easy to fall back into a linear process. But learning is a cycle—not a once-through process with a beginning and an end. Once you have designed and tested an intervention, it is time to shift into the active side of the learning cycle. This process includes taking action, seeing the results, and then coming back to examine the outcomes from a systemic perspective.

Michael Goodman is an internationally recognized speaker, author, and practitioner in the fields of systems thinking, organizational learning and change, and leadership.

Richard Karash is a founding trustee of the Society for Organizational Learning, a founding member of the SoL Coaching Community of Practice, and a co-creator of “Coaching from a Systems Perspective.”

Editorial support for this article was provided by Colleen Lannon.

SIX