There is a lot of talk in the business community about “people being our most important assets.” It sounds like a good idea — recognizing people as valuable assets as opposed to line item expenses. But has the idea been translated into fundamentally new actions and policies? A quick glance through the financial statements of any organization reveals that, when it comes to the bottom line, we have not changed our thinking about people as expenses. “People” only show up as a cost of sales, a selling expense or an R&D expense. On the balance sheet, they appear as payroll liabilities.

If people really are a company’s most important asset, it is strange that most companies do so little to keep track of, understand, and benefit from their full capabilities. Aside from things like number of employees, payroll costs, and headcount by department or function, there is little information available for assessing the intellectual capital of an organization. Yet there is an abundance of usable information for managing capital equipment, patents, inventories, and other physical (or financial) assets.

If financial statements were merely used as snapshots for reporting an organization’s status to its stock-holders, this omission would not be a problem. Unfortunately, financial accounting data is also used for managing the business (see “Double-loop Accounting: A Language for the Learning Organization, February 1992). As long as we manage our organizations according to current financial accounting measures, people are likely to be treated as variable costs and nothing more.

Redefining “Assets”

If you were to ask a coach or a conductor about the capacity of a team or orchestra, he or she would be able to tell you in great detail about the capability of each individual. Their job is to understand and build upon those individual capabilities to enhance the capacity of the whole group. They create synergy by making the whole performance more than the sum of the individual parts.

“In our current system, “as employees grow more productive, they show up as higher expenses. When times are good, the higher expenses are ‘covered.’ But when times get bad, people tend to be seen as expenses that can be cut.”

A lot of good managers see their job as precisely that of coach and mentor. They understand the organizational needs and recognize the importance of developing people who can meet and exceed those needs. But how does that normally get translated into an organization’s financial statement? The people who are “appreciating” are given promotions and raises which show up on financial statements as higher expenses — without a concomitant visible increase in the asset base of the company. As employees grow more productive, they show up as higher expenses. When times are good, the higher expenses are “covered.” But when times get bad, people tend to be seen as expenses that can be cut.

A football team does not lay off half of its starting players because it had a bad season and revenues were down. To try to go through a season with half as many players is not going to improve its chances of winning. Of course, it is a lot clearer what capabilities are necessary to create a winning football team than those of a successful company. In the absence of such clarity, we hire and fire people as if only the total number of people is important and not their capabilities. What if we really treated employees as assets — not just in words but on our financial statements? For starters, we would add another category in the asset column and devise a way to assess the value of the intellectual capital of the organization. Unlike physical assets, people assets could appreciate over time. We would still account for people’s salaries, benefits, and other employee-related costs as expenses, but we would also have a corresponding valuation for the people-capacity of the organization. The people-asset column would provide corporate visibility that the people-capacity was being enhanced.

New Internal Measures

How should the belief that employees are a company’s most important asset be translated into visible actions? How can an organization actually operationalize that value into something that can make a strategic difference? To address these questions, we need a framework for identifying what “people-capacity” is and how that capacity can support the needs of the organization.

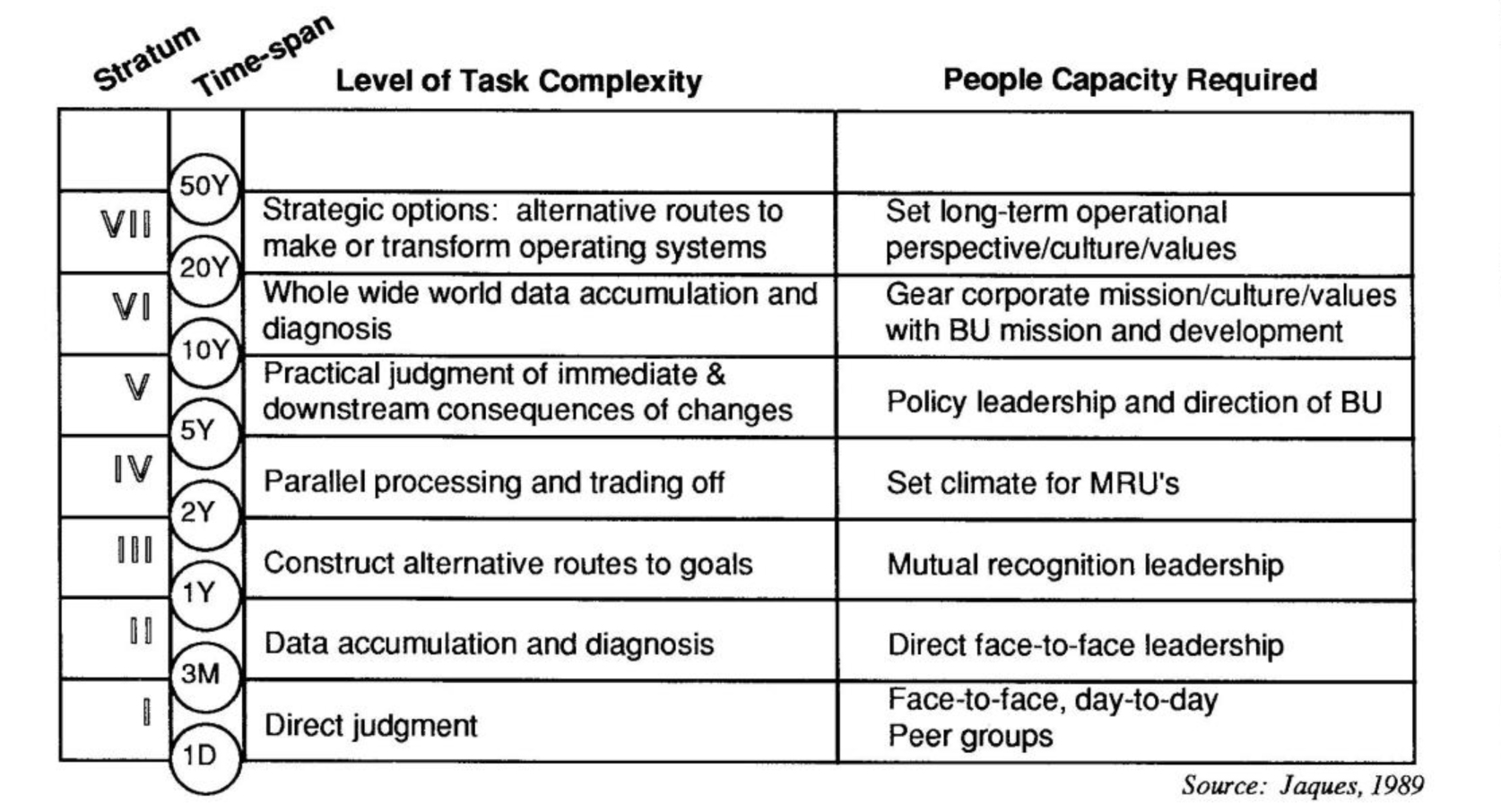

One possibility can be found in the book The Requisite Organization by Elliott Jaques (Cason Hall, 1989). Jaques proposes that the work of any organization falls into eight different strata, each corresponding to a specific time-span. For the learning organization, the eight levels can serve as broad categories in which one would want to develop their people-assets. Internal measures could be developed to see how well one is progressing on developing people’s effectiveness within each stratum. Jaques even proposes an equation for evaluating people’s “working capacity” as a function of cognitive power, skills, and task type.

The nature of the work, as defined by the time-span measure, could determine the compensation as well as the fit of a person to fill that position. A person who is capable of constructing alternative mutes to goals (level 3), for example, may have great difficulty moving into level 4, which requires parallel processing and trading off among alternatives. When the actual working capacity in any of the strata exceeds the required working capacity, some people can be redeployed either within the organization or outside the organization (perhaps to nonprofit companies).

Putting employees on the balance sheet as assets could also change the way we think about cost-cutting. Training would be viewed as an investment and would not be automatically cut when times get tough. Vacation days would be considered vital investments that help our most important assets become even more productive. Employees would not be seen as expenses to be cut out, but assets which we could invest in and expect to get a return in terms of higher productivity, new products, better quality, and a myriad of other possibilities that we have not yet begun to identify.

The Learning Organization’s Dilemma

Being able to track the appreciating value of people-assets could help address a dilemma that arises out of continual learning and improvement in worker productivity. A Vice President of Quality at a semiconductor manufacturer posed the dilemma this way: If a company is pursuing quality improvement and the productivity of the workforce is continuously improving, either the company has to keep growing at the same rate or it has to continually reduce its workforce.

His experience told him that an annual improvement of 20% was reasonable and sustainable over a long period of time. But if the company improves productivity by 20% (that is, the same number of people can produce 20% more than before), what should they do with the additional people that are freed up? He argued that the only options were to keep growing the company (by expanding current business or redeploying the people into new markets) or layoff the workers (and distribute the additional profits to the stockholders). When his own company was unable to expand during a drawn-out industry slump, people were laid off. The message to the employees was that they were improving themselves out of a job. Improvement rates slowed considerably.

A learning organization faces a similar problem as it learns to become more effective on all fronts. The rate of improvement can be substantially higher than 20% per year, which may make the pain of the productivity growth even more acute. What happens as people “learn” themselves out of their current jobs? If they are redeployed into new markets, continually expanding the company, the organization as a whole could either hit diminishing returns as it expands and loses focus, or it might have to lay off its workers. Neither alternative is very attractive.

Direct Channel to the Community

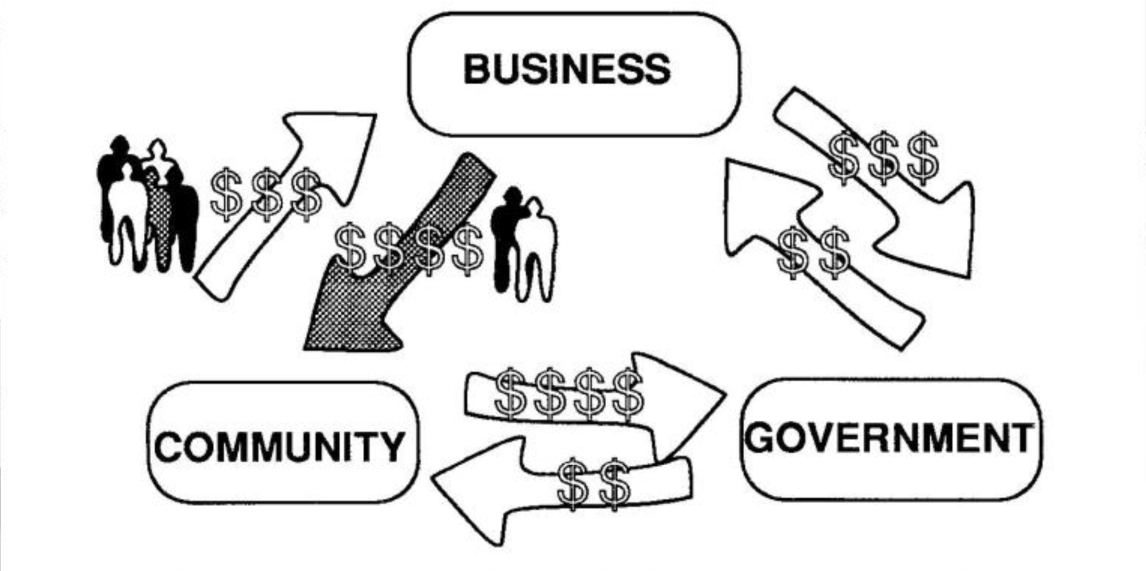

The ability to take “people-deductions” allows companies to deploy some of their workforce directly into the community. This short-circuits the usual flow of money: from companies through the government (social services, research funds, and grants), and — after much delay and many dollars chewed up in the process—to the community.

A Modest Proposal

One possible solution to this dilemma is to allow companies with appreciating people-assets to contribute those employees who wish to take on a new challenge to a non-profit organization for a period of time and take a tax deduction for it.

By allowing companies to redeploy their people-assets outside of the firm, a number of problems can be addressed. First, it gives companies an option other than endless expansion or layoffs. It can also provide employees with tremendous opportunities which they normally would have to leave the company to pursue. Second, it helps address non-profit companies’ need for technical expertise and experienced professional managers. Matching the asset of a knowledgeable worker with the needs of a nonprofit can be far more valuable than any monetary contributions. Third, corporations can become more directly involved in the role of distributor of wealth within their local communities. Corporations have always been wealth creators as well as wealth distributors, but the emphasis has been more on creation. Distribution of wealth has primarily come in the form of employment, dividend payments, and charitable donations.

Allowing such tax deductions for such actions begins to blur the artificial distinction between for profit and non-profit organizations. Both types of organizations are responsible for producing the maximum return to their stakeholders. From a systemic perspective, however, the distinction is artificial in the sense that we are all stakeholders to varying degrees in both types of enterprises.

Think Globally, Act Locally

Implementing this proposal could radically change the role of both business and government in community development (see “Direct Channel to the Community”). Currently, the U.S. federal government serves as the largest centralized institution for redeploying wealth back into the communities. The bureaucracy required to run such a system rivals the now-dismantled system of the former Soviet Union. The federal government’s role could shift toward providing the laws, incentives, guidelines, and information to work toward the common good. The people and organizations closest to the local conditions could have the freedom to act in their local interest — thinking globally, acting locally.

As the role of business becomes redefined as an active community player, perhaps a new corporate measure will become a standard by which a company will be assessed by society — its nonprofit-to-profit (N/P) Ratio. The ratio could serve as an indicator of how effectively an organization can develop its people-assets to create a surplus that would them support the work of nonprofits and social programs. The higher the ratio, the more effective the organization is in producing returns to society.

By giving a tax deduction for redeploying employees in nonprofits, much of the means and responsibility for community development and social work can be turned over to those who are local citizens (individuals and corporations). It will not only redefine the role of government, but also the purpose of business.

The scope and scale of change implicated by such a shift is enormous and would require a long time horizon. But then, the current system is in need of a serious overhaul. The Social Security system is basically bankrupt. Poverty and homelessness is on the rise. Bureaucratic inefficiencies continue to chew up millions of dollars (as well as people). Our education system is in a state of crisis and lags far behind that of most industrialized countries.

As Professor John Sterman of the MIT Sloan School of Management pointed out (“Not All Recessions Are Created Equal,” February 1991), the downturn of the economic long wave “is a time of radical change.” The imbalances it generates spill out into the social and political realm, creating new threats and opportunities — in effect, changing the rules of the game. Just as the seeds of the growth of the federal government were sown at the last trough of the long wave, perhaps a new direction can be plotted as we near the bottom of the current cycle.