In the last few years, the nation’s largest hotel chains have loosened the reins on employees. The industry, which was badly overbuilt in the 1980s, has had $16 billion in losses in the past three years and desperately needs to cut costs while improving service. One answer: Lay off managers who used to supervise the front-line staff, and give those employees authority to better serve customers.

“Critics say employee-sponsored largesse can be very costly, particularly if workers are not given sufficient training on how far to go to accommodate guests. What’s more, these critics contend, giving employees greater authority to correct mistakes can be used to mask deeper problems. ‘Hotel companies are using front-line employees for damage control and calling it empowerment,’ says Chekitan Dev, assistant professor of hotel marketing at Cornell University.” (“Now Hotel Clerks Provide More Than Keys,” The Wall Street Journal, March 5, 1993)

Side-Effects of Empowerment

With this shift in authority, the ability to do whatever it takes to satisfy customers extends not only to people at the front desk, but to all hotel employees. At the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco, where an empowerment program was adopted two years ago, employees can give away almost anything to ensure customer loyalty, from a free terry-cloth robe to bill write-offs for unhappy customers. Recently, the Fairmont Hotel paid over $3,000 for clothes, toiletries and other necessities for a Uruguayan couple who accidentally had a bellman place their luggage in another guest’s rental car (which was headed for Oregon).

While employee “empowerment” programs have been crucial to the success of companies such as WalMart, Inc., oftentimes the only authority hotel industry employees have is to satisfy disgruntled customers. When the goal be-comes pleasing the customer at any cost, the focus is taken away from finding a cost-effective and efficient way to run the hotel, especially if employees are given responsibility with little or no training regarding appropriate resolutions. The result: a potential “Shifting the Burden” situation.

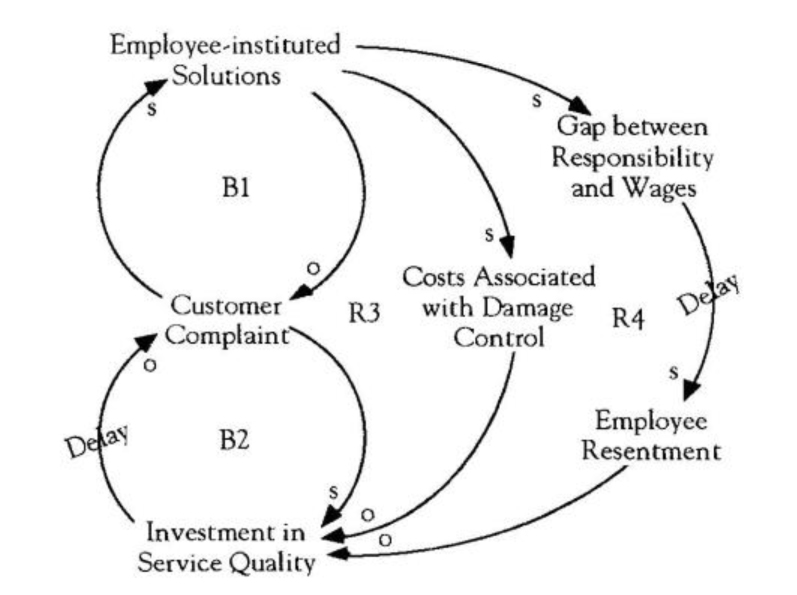

As is common in a “Shifting the Burden” structure, the underlying problem generates symptoms that demand attention, resulting in quick fixes to satisfy disgruntled customers (see “Side-Effects of Empowerment”). Over time these short-term solutions begin to cause more problems, which erode the hotel’s ability to invest in long-term solutions.

In the hotel industry, the need to cut costs and maintain quality service in order to remain strong competitively has led to workforce scale-downs and a shift in power to front-line workers who can respond to customer complaints more quickly (BI). Empowering front-line workers to provide quick fixes could, however, take attention away from finding ways to provide quality service up-front at lower cost (B2). The focus then becomes one of keeping customers happy after-the-fact, regardless of the expense. Employees may have little comprehension of the bottom-line impact of their actions, resulting in high costs associated with damage control (R3). This may eventually affect the quality of overall service. Meanwhile, the gradual erosion of service quality is masked by happy customers, as well as employees who presumably perform better as a result of their increased authority. However, if wages do not increase along with responsibilities, a rise in employee resentment could occur. Over time, this could jeopardize the very service that empowerment programs were intended to improve (R4).