Carver Corp. was on its way up.

During the mid-1980s, like many other organizations, this company boasted rapid growth and increased revenues. A manufacturer of special audio-electronics products, Carver Corp. serviced a growing core of clients who were willing to pay a higher price for better-sounding, better-quality innovations. Its products were well-received for two reasons: experts said Carver products really did sound better, and owner Robert Carver labeled his innovations in ways that made them seem “as special as they were” (“Eliminating the Static,” Nation’s Business, September, 1989).

With a solid reputation, a strong client base, and a network of 460 dealers, Bob Carver went public in 1985. But problems associated with the subsequent rapid growth soon led the company into financial trouble.

Although Carver says going public did not distract the company, subsequent problems suggest otherwise. Carver had promised the investment banking community that immediately after going public the company would develop in-depth management. Carver, however, did not bring in new people from the outside until about a year after the public offering. When they finally did bring in experienced management talent to develop better systems, the move did not allow Bob Carver to allocate as much time to R&D as he had hoped. Instead, corporate expenses exploded, and productivity went down. The problem was attributed in part to the fact that the new managers did not fully understand how Carver Corp. worked and took actions that were counterproductive.

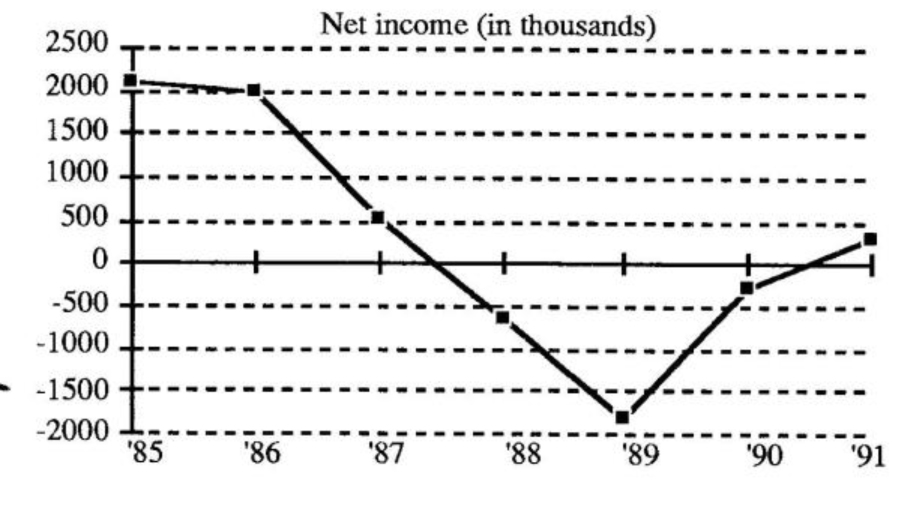

Carver's Income Slide

Meanwhile, the company was losing market strength partly because of their resistance to introducing models with simple cosmetic changes. As the company was not introducing enough new products to keep customers interested, their dealer base began to deteriorate. In 1989 Carver had 230 dealers — half as many as it had in 1986. Marketing also suffered from a lack of attention. Carver stopped pushing for product reviews — even as he acknowledged that “no reviews mean customers forget about you and your products.”

The diversions took their toll on the company’s financial health. Net income skidded sharply after 1986 (sec “Carver’s Income Slide”), followed by a heavy sales slump in 1988. A short-sighted executive cut costs by laying off one-third of the workforce, but when sales rebounded, the company could not rebuild its staff fast enough. Manufacturing problems also became evident as operating losses increased despite a $3 million increase in sales. (“Growing Pains Almost Killed Carver,” Industry Week, July 2, 1990, p.30)

During the second half of 1989, Carver tried to get back on track by developing and releasing 18 new products. But while developing these new product lines, the core products became dated. In September, Bob Johnson came to Carver Corp. to try to turn the company around — by investing in productivity and implementing quality measures. Johnson also worked on reducing materials costs, reorganizing design processes, and expediting costs. But he only stayed until the end of the year, leaving Carver’s financial future in doubt.

Bob Carver took over once again in 1990, and during that year he saw net income rebound and sales increase 27.4 percent over those in 1989. Under his direction, Carver Corp. improved purchasing practices, increased operating efficiencies, and cut expenses. This time, Carver hoped the quality improvements would make a lasting difference. But the continuing cycle of ups and downs that followed Carver’s rapid growth suggest an uncertain future for the company.

Discussion Questions

- What was Carver’s growth engine?

- As Carver grew, what internal limits created problems?

- How did the delay in hiring additional outside management talent exacerbate the capacity problem?

- In “Growth and Underinvestment,” delays play an important role. What were the significant delays experienced by Carver?

- How can you know whether your organization is a victim of its own underinvestment tendencies?

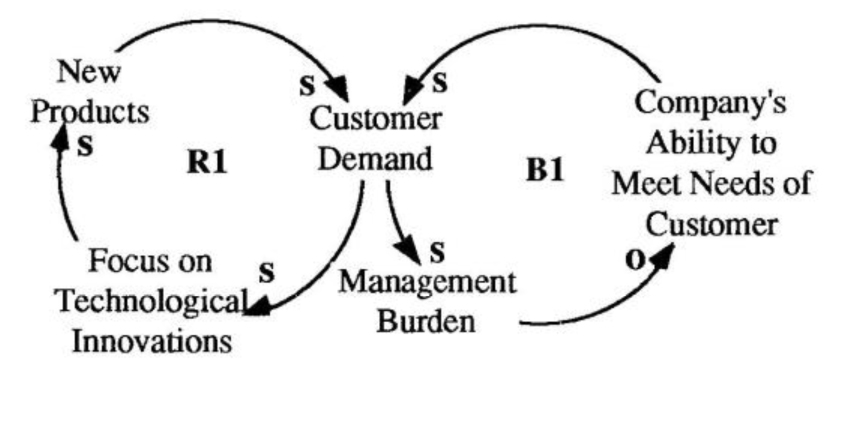

From the beginning, Carver Corp. developed a strong following by focusing on continual technological improvements, which allowed them to offer innovative high-fidelity products (see “Carver’s Limits to Success”). Carver established a strong market presence as more people discovered their high-quality products, encouraging them to continue a strategy of pursuing technological innovation (RI).

As customer demand continued to grow, so did the managerial challenges of running the ever-expanding operation. The growing management burden began to affect the company’s overall ability to meet the needs of the customer, leading to a drop-off in customer demand (B1). As the company outgrew the capabilities of its existing management systems, areas such as R&D and marketing were neglected.

Carver's Limits Limits to Success

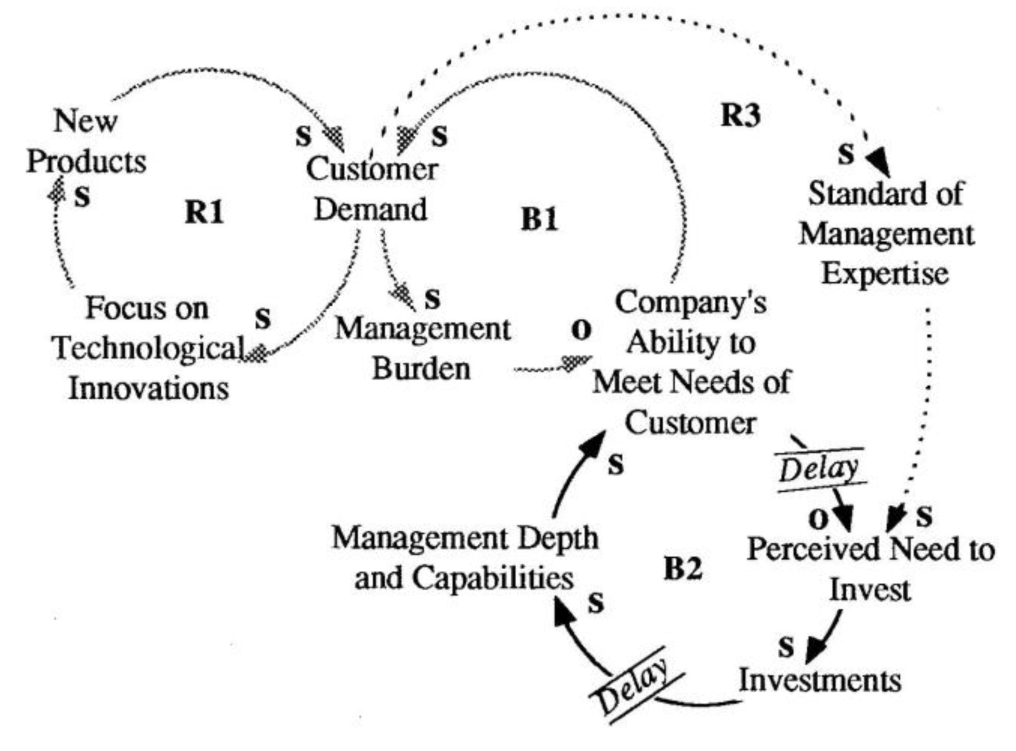

After the company went public in 1985, Carver did not invest in developing additional management talent right away (see “Underinvestment in Management Depth”). In the beginning, the need for such an investment did not seem very urgent to Bob Carver, since the company had always gotten along by recruiting management from within. The insistence of the investment community accelerated his decision to bring in outside experience — both to increase the management depth and improve the company’s ability to meet the needs of the customer (B2). Unfortunately, Carver underestimated the time delay required in actually developing that management depth. As a result, the situation worsened as productivity plummeted and costs soared. The deteriorating results further distracted them from attending to critical areas of the company.

Underinvestment in Management Depth

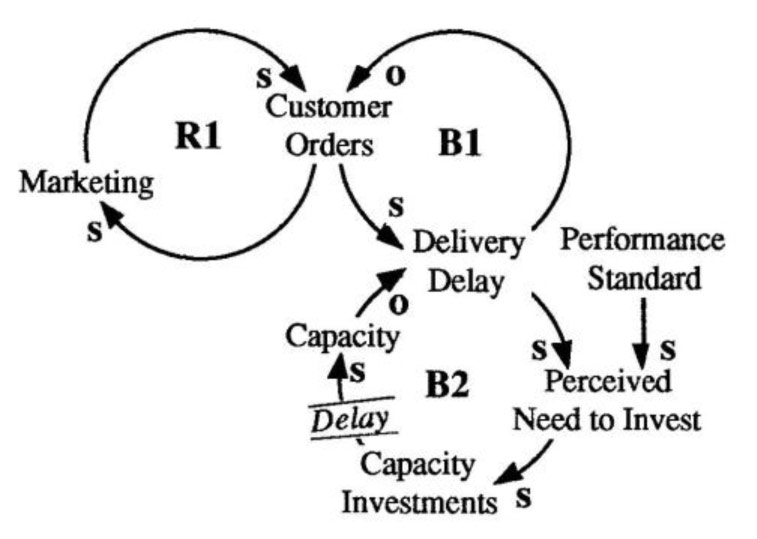

Hidden Danger

In “Growth and Underinvestment,” there is a classic systemic race between the two balancing loops (B 1 and B2). As growing customer demand puts stress on the organization, it creates a balancing effect which counters the growth in demand. At the same time, it sends a signal to those inside the organization that they need to invest in additional capacity of some kind. The question is whether one can bring on new capacity fast enough before the balancing effects of B1 drive away customers for good.

There is also another effect which is more subtle — the reinforcing loop that is traced out by a figure-8 formed by the two balancing loops (see “Unfolding the Underinvestment Cycle”). When the company’s ability to meet customer needs deteriorates, customer demand falls, which effectively decreases the management burden and seemingly improves the company’s ability to handle this lower level of demand. This leads one to believe that capacity investments are not necessary, so investments are not made (or decisions are made to reduce capacity). Consequently, the ability to meet customer needs suffers, thereby lowering demand even further (R2). Each cycle of non-investment leads to lower demand, which justifies the “no investment” action the next time around.

In the meantime, the initial engine of growth can also be kicked in reverse, accelerating the decline even more. In Carver’s case, as customer demand fell, Carver lost its focus on technological innovations, which led to fewer new products and lower demand (R1).

Double Delay

The key to managing this archetype lies in the ability to invest in the requisite capacity in a timely manner. The difficulty is that there are usually two sources of significant delay, either of which can hurt the outcome. The first is a perception delay — the time it takes to perceive that the current level of performance is deficient enough to take serious action.

In Carver’s case, management did not perceive the need to invest in management capacity right away because their current ability appeared to be in line with their previously established standards of management practice. It was not apparent that the underlying nature of the management challenge had changed as the company’s revenues topped the $20 million mark. The old performance standard on which they were basing their investment decisions was no longer appropriate. By trying to “make do” with their existing staff, they ended up spreading their attention too thinly. Consequently, product reviews were neglected (which hurt their market presence) and the lack of new products hurt their market attractiveness and image.

Once a decision is made to invest, however, a second delay — in capacity acquisition — means that the company’s performance will not improve immediately. In fact, things can get worse before they get better. Underestimating this delay can lead to taking premature countermeasures that might aggravate the situation. One could, for example, double the investment because the initial measures seem to be inadequate. This could result in overcapacity, which could lead to over fiddling, as well as more costly operations. Or capacity additions could be cancelled, due to a lack of understanding that more time was required for them to fully develop and provide payoffs. Both actions would further undermine the company’s ability to meet customer needs.

Carver apparently underestimated what it would take to get outside managers to work effectively. Hiring people who were technically competent but unfamiliar with how Carver worked proved to be a liability rather than an asset. The new managers took actions that undermined the close relationships developed between the company and the people who made their labor-intensive devices.

Capacity Constrained Growth

A key question that the “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype raises is “How do our own actions limit our own market potential?” When you review your organization’s performance, how can you tell whether the downturns you experienced were not of your own making? Traditional accounting measures and business performance indicators have been designed with the implicit assumption that the market is “out there” and the company responds as best as it can to external events.

In order for us to see how our actions create the environment we perceive as “out there,” we need to begin by identifying the feedback loops that connect the actions we take (or don’t take) to the market. This requires a much deeper understanding of what the customers really need and how well we are equipped to meet those needs. One of the cornerstones of the Total Quality Management (TQM) paradigm is a “market-in” philosophy versus a “product-out.” In terms of the “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype, this means making a link between customer demand and a company’s own internal standard of performance. As customer demand grows, standards of management expertise should increase. This sends an early warning signal that investments need to be made (shortening the perception delay). As the investments come online, the company is able to serve customer needs better — which helps to push demand higher (R3 in “Underinvestment in Management Depth”).

Unfolding the Underinvestment Cycle

Creating such a reinforcing loop can short-circuit the ill effects of the two balancing loops, but it often means making investments ahead of traditional signals that usually trigger such decisions (such as deteriorating performance in meeting customer needs). The challenge lies in understanding a customer base well enough to know whether the growth in demand is more dependent on your ability to deliver on your company’s reputation than on other factors beyond your control.