These comments came from production workers at Rhino Foods, a specialty dessert producer in Vermont. Although I have worked with many companies, the spirit at Rhino strikes me as unusually friendly, personal, and accepting. The workers feel that they are supported and valued, and the company culture exhibits a high level of trust and collaboration.

How did the people at Rhino Foods create such an atmosphere? What actually goes on within and between people that fosters “healthy connection” or “community?” And how will this “community” help Rhino Foods become a learning organization?

In order to become a community of learners, we must be willing to inquire into our deepest assumptions. As we take those initial steps outside of our comfort zone and begin learning how to work and be together in new ways, we may find that building community is one of the most challenging aspects of the learning organization journey.

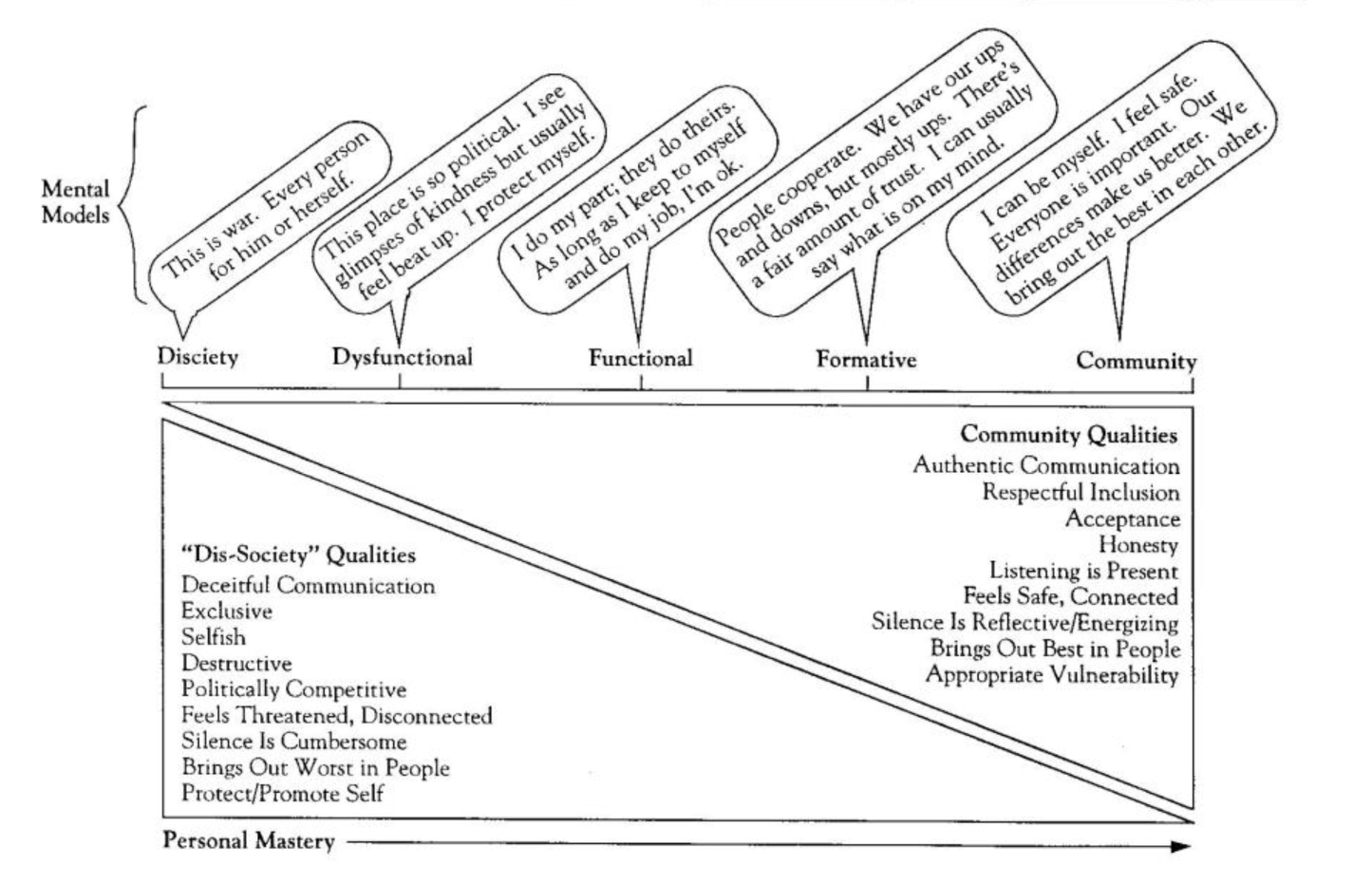

Many traditional, hierarchical organizations are struggling with long histories of distrust, detachment, and little companionship. Unfortunately, these patterns of alienation are a lot more common in organizations than patterns of community. Yet, even in organizations characterized by alienation, some pockets of healthy relationships and behavior endure. Consequently, community is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon. All groups, including Rhino Foods, exist somewhere along the continuum of “living in community” — and their placement on that continuum shifts continuously. Determining the location of your team or organization on that continuum is the first step in building a community of learners.

” Disciety “

When people in a group feel secure, trusted, and connected, and consider themselves partners in creating a learning environment, that group can be characterized as having a high level of community. On the other hand, when people feel threatened, misled, and undervalued in a group, and act in ways that make others feel the same, the relationships are devoid of companionship or community. This far end of the continuum represents society at its worst — what I call a “disciety” (dis-society).

We may find that building community is one of the most Challenging aspects of the learning organization journey.

In a company that operates in disciety, individuals or teams may exaggerate budget requests to get more resources, or lie about their results, skills, or abilities in order to look good. A common sentiment is, “I have to be political in order to survive.” Employees spend a great deal of time and energy determining which side they need to be on, who their allies are, and how they can best protect themselves. The goal is not to pursue what is most beneficial for the team or company, but how to look impressive or get ahead.

Because of the huge energy drain this creates, people do not push themselves unless they see the potential for personal gain; they do the minimum just to get by. Over time, dysfunctional relationships between individuals and departments develop. These differences can lead to conflict and tension, and it becomes more important to make a good point than to listen and understand. As a result, meetings resemble a battlefield where more energy is spent pulling and tugging than reflecting or comprehending.

Qualities of Community

In contrast, a community such as the one at Rhino Foods can bring out the best in people. Such a community is characterized by mutual service, encouragement, and support. It is based, first and foremost, on authentic communication — a natural, truthful, and honest revealing of one person to another in an open and accepting relationship (see “Community-Building Dynamics”).

Because people feel safe, they can feel comfortable expressing their concerns, desires, expectations, and accomplishments, even if they fall short of personal or company expectations.

For example, in the midst of a dilemma at Rhino Roods, founder and CEO Ted Castle employed the values of community to work collectively on a solution. An anticipated drop in orders had led to production overcapacity. Rather than lay off workers, he chose to disclose the problem to all of the employees at a company meeting.

At this meeting, Ted asked for a task force to develop solutions consistent with the company’s stated vision: “Rhino Foods is a company whose actions are inspired by the spirit of discovery, innovation, and creativity. Our purpose is to impact the manner in which business is done.” He allowed the group significant autonomy, which increased their security and encouraged them to be honest and vulnerable.

The result was a unique alternative: instead of downsizing, Rhino Foods initiated an exchange program in which certain Rhino employees would temporarily go to work for other companies. This enabled the partner companies to fill their personnel needs with skilled workers on a short-term basis, while Rhino workers continued to receive paychecks. This creative solution allowed Rhino to maintain internal morale and avoid significant financial losses.

Community-Building Dynamics

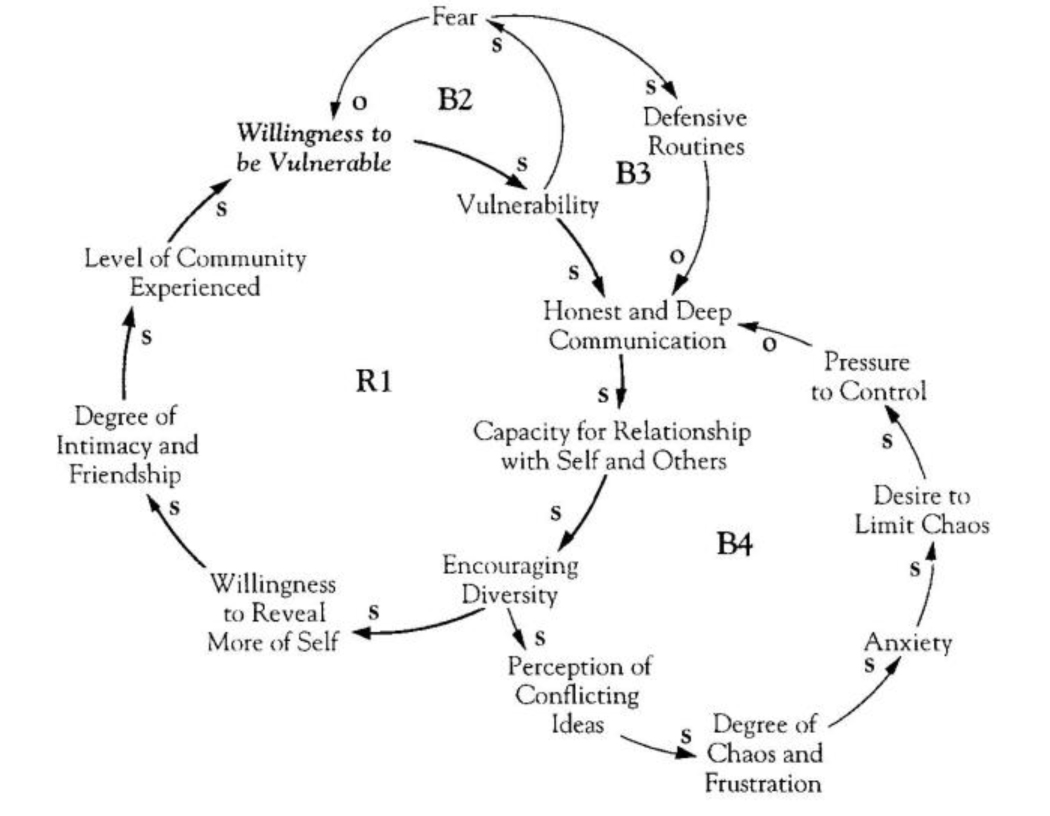

The reinforcing process of community-building begins with individuals’ willingness to be vulnerable. Becoming more vulnerable opens up honest and deep communication, which expands one’s capacity for relationship with self and others and encourages greater diversity. With increased diversity comes a greater willingness to reveal more of one’s self, which deepens intimacy and heightens the experience of community, further reinforcing people’s ability to be vulnerable (R1).

There are, however, balancing forces that can thwart community-building efforts and kick the reinforcing process in reverse. Increasing one’s vulnerability can lead to heightened fear, which can decrease one’s willingness to be vulnerable (B2), and/or the fear can trigger defensive routines that shut down honest communication (B3). In addition, increased diversity can lead to conflict and increased frustration, followed by a desire to limit chaos and to control — all of which counter efforts for honest and deep communication (B4).

Community Spectrum

No group is ever continually in community. The continuum between community and disciety depicts the different stages people experience when moving in and out of community (see “Community/Disciety Continuum”). In order to enhance learning in organizations, it is important to work toward fostering an environment that is consistently closer to the “community” end of the continuum.

There are three stages of development between Disciety and Community — Dysfunctional, Functional, and Formative. The Dysfunctional stage is the one closest to Disciety, and is characterized by politics and pain. In the Functional stage, people are basically left alone as long as they do their job. The Formative stage, however, is where people begin to cooperate and share their personal thoughts. Finally, Community is a place of safety in which diverse views and individuals are accepted.

In order to move a group toward community, individuals need to begin or further their practice of the disciplines of community (see Community Qualities in “Community/Disciety Continuum”). Practicing these disciplines can help move a company’s culture from one place on the continuum to the next. For example, “Listening is Present” may mean that the person in charge of a meeting provides time for workers CO share whatever is on their mind. “Respectful Inclusion” might mean that a manager shares information received from superiors, or includes constituents in the decision-making process. Each of these disciplines of community has an opposite quality that promotes disciety; the challenge is to recognize which qualities are being expressed at any one time and purposefully work toward developing those that enhance community.

Whatever your current reality, living the journey of community building is more natural and important than attempting to preserve a specific condition. Over time, as a group practices the disciplines of healthy relationships, it may one day find itself “in” community, a space characterized by support and safety. This is a peak experience occasionally felt during the process. Like any feeling, however, it continually changes. Therefore, a mature group may bask in, but never cling to, the feeling of being “in” community. Instead, it learns to continue practicing the disciplines of healthy relationships while accepting its present condition.

Whom Do You Want to Be?

Where is your company on the community continuum? Where do you want to be? There are three factors to consider in determining a group’s placement on the community continuum: condition, intention, and action. These factors represent a group’s current reality, its vision, and what it is doing to close the gap. To determine a group’s condition, we need to survey the group’s experience of safety, authenticity, connectedness, and respect. The greater the number of individuals who are experiencing these characteristics, the healthier the relationships. Second, intention reveals what a group wants or desires. Questions that surface a group’s intentions include, “Do we want to overcome our disagreements?” and “Are we willing to be honest and work to resolve this issuer’ The group’s actions determine its present ability. By observing communication patterns such as behavior at meetings, etc., it is possible to see what a group is currently able to do and where it needs to work more.

For example, after someone makes a suggestion or offers a new idea in a meeting, do you hear, “Yeah, but…” or “Maybe, but I think…” or “I disagree. I believe…”? If so, the group members may need to practice suspending judgments in order to improve their listening. On the other hand, if you hear “Why do you suggest that?” or “Say more about your idea,” and members take the time to respectfully listen and understand one another, then deeper and more authentic communication is being practiced.

Community/Disciety Continuum

It is critical to remember, however, that actions alone do not reveal a group’s direction or condition. Community is not determined by the presence or absence of pain or conflict, but by a group’s ability to deal with those issues. A group of people who are experiencing conflict or pain may appear to be moving toward disciety, but if their overall intent is one of care, concern, and commitment, this experience is a likely step toward community. On the other hand, people in a similar situation who are working toward individual gain at the expense of the whole are probably moving toward disciety. Consequently, both intention and action arc critical determinants.

Community in a Learning Organization

The process of developing a learning community touches upon all of the disciplines of a learning organization. For example, a shared vision provides the purpose, coherence, and energy for the organization. But in order to uncover what visions matter to people, the people themselves need to matter. Therefore, a genuine respect and concern for personal visions is one of the building blocks for a shared vision.

The process of building a learning organization also promotes continual examination, reflection, learning, and growth. It strives to uncover limiting behaviors and attitudes, while developing a deeper awareness of the structures and events that foster them. In order to receive honest input and personal commitment from employees, a relative level of security must exist. When people feel comfortable, it is easier for them to risk “not knowing” and there-fore to open themselves to learning.

For example, Rhino Foods stimulates input and deepens trust by scheduling “listening” sessions before each production shift begins. This session allows all personnel to voice concerns and hopes for the upcoming day. The position of listening session leader rotates among all experienced workers; because of the rotating leadership, a degree of trust has been built over time.

Pitfalls, Illusions, and Stumbling Blocks on the Road to Community

Before we embark on the process of building community, it is important to be aware of the potential dangers. The path toward building authentic learning communities is dotted with land mines and stumbling blocks. Many of them are merely myths that we must challenge if we are to achieve true community:

Myth #1: “If we build community, money will follow.” Not so. It is possible to do all the right things, live with integrity, and not necessarily make more money. Community and profitability are not synonymous — but employees who find greater meaning and purpose, develop better communication, and work more easily together will naturally be drawn to organizations with a high level of commitment to community. Organizations with employees committed to a common vision, team-work, and honest communication are an enviable resource. This resource often improves the health and profits of an organization over the long term.

Myth #2: “Community and hierarchy are incompatible.” An organization with leaders who are willing to listen, respect, and serve employees can go further in creating community than a group of equals who are unwilling, unable, or both. The presence and practice of community-building disciplines is thus more critical than the presence or absence of hierarchy.

Myth #3: “Building community is the responsibility of top management.” The idea of building community may start of the top, but how far it spreads depends on the drive and commitment of people at all levels. If management “railroads” the community initiative through the organization, it is doomed to fail. The more mutual the endeavor, the better the results.

Myth #4: “A community building program will create community.” Programs or initiatives do not create community, people’s desires and actions do. Developing healthier relationships takes time, energy, and commitment. It is better to start small and build momentum than to create high expectations and be disillusioned.

Rhino Foods also recognizes that community is an important factor for nourishing “personal mastery” or personal growth. Rhino encourages employees to increase their personal mastery through its WANTS program, in which Rhino employees facilitate other employees on achieving personal goals. The goals do not need to deal with improving Rhino — and the specific wants an employee works on with his or her facilitator, on company time, is confidential and up to the employee. The employees who facilitate this process with others arc trained by the company. Marlene Dailey, director of Human Resources, points to the WANTS program as a contributing factor in the company’s high morale and low employee turnover.

Knowledge and Commitment to Community

To know about community and to know community are quite different. The first implies that building a community is simply about learning a few concepts, designing a series of trainings, and charting the impact on performance to determine whether the initiative is successful. The latter, to “know” community, requires being personally committed to and involved in a deeper and more profound process.

Knowing community means committing your whole self to a way of interacting with people that promotes respect, tolerance, and growth; to a process of living that begins but never ends; and to relationships that go deeper than simple appearances.

Community is thus both a process (directed by intention and action) and a place (a particular condition). The more people work at being together in the process, the better they become at being a community. Ultimately, community is both a way of being and a place to be — a journey and a destination.

Greg Zlevor is president of Westwood International (Westwood, MA), a consulting firm. Firm regularly leads community budding workshops for the Foundation for Community Encouragement, and has worked with M. Scott Peck on the theory and practice of group work. Editorial support for this article was provided by Kellie T. Wardman. The “Community Building Dynamics” diagram was developed with assistance from Stephanie Ryan and Craig Fleck.