Truck sales are on a roll…. US sales of light trucks stormed ahead 24% in January, to 416,828 vehicles, easily outpacing a 7.8% rise in car sales. … Call it too much of a good thing. Suddenly, Detroit is scrambling to meet demand for its hot-selling trucks—pickups, minivans, and sport-utility vehicles such as the Ford Explorer. … The big worry now: that Motown will let quality slip as it expands production.” (“Detroit: Highballing it into Trucks,” Business Week, March 7 1994).

• • •

Drifting Quality

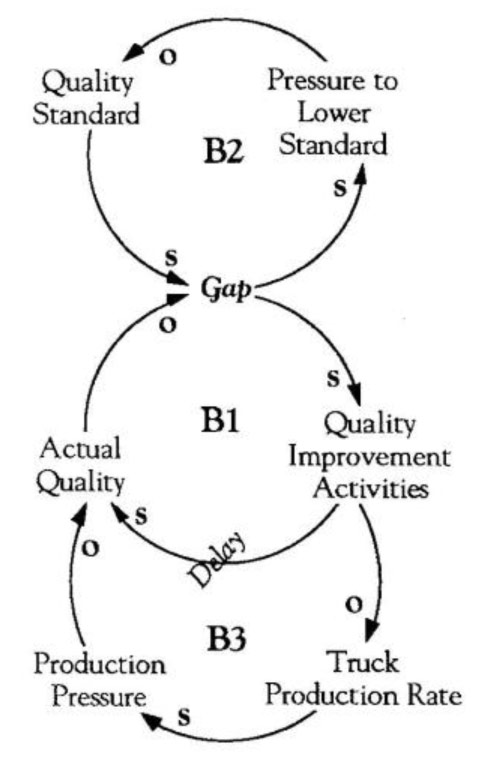

A gap between the quality standard and actual quality can be resolved by implementing quality improvement activities (BI), but delays inherent in this process often compel organizations to let, the standard “erode” (B2). Improvement activities are also likely to lower production rates in the short term, which can then lead to higher production pressure and quality (B3).

The Big Three automakers are investing heavily to meet demand as truck sales rise to 39% of the U.S. light vehicles market. Chrysler — with 59% of its vehicle sales in trucks — has actively focused on this market, and Ford and GM are following suit.

The payoff comes from the generous margins that truck sales provide. According to Business Week, Chrysler earns an average of more than $7,000 on its Jeep Grand Cherokee and $5,000 on its minivans, versus a Detroit average of $4,000 on a midsize sedan.

But the question facing the Big Three is how to meet the strong demand for trucks without investing in new plants—a strategy that could become disastrous if the market turns down. General Motors is increasing production by running some of its factories around the clock. Meanwhile, Ford Motor Company spent over $650 million to add the F-Series pickup to its Louisville plant.

This drive to expand production may create new problems, however, if the rush to produce vehicles compromises the quality of the trucks. According to Business Week, Chrysler has already recalled its Ram pickup twice and the Grand Cherokee four times, creating concerns about quality.

If the Big Three allow the quality of their products to slip, they may fall into a “Drifting Goals” structure (see “‘Drifting Goals:’ The Boiled Frog Syndrome,” October 1990). In a “Drifting Goals” structure, one of two balancing processes can close the gap between a goal and current reality. One way to reduce a quality gap is to implement improvement activities which will bring the actual quality more in line with the standard (B1 in “Drifting Quality”). Inherent delays, however, often compel organizations to look for other alternatives that bring more immediate results—such as letting the standard “drift” or “erode” to become more in line with the actual (B2). By alleviating the gap in that way, the pressure to continue quality improvement activities declines. But over time, this dynamic creates a downward spiral of ever-decreasing quality.

The pressure to just “get the trucks out” to the waiting buyers can lead to a deterioration in actual quality as workers are pressed to boost production. In an environment where there is high production pressure, it becomes even more difficult to stay focused on improving quality because improvement activities (e.g., preventive maintenance) are likely to lower production rates in the short term, which then leads to more production pressure and lower quality (B3). As the gap grows wider, the pressure to lower the standards increases, leading to an erosion of those standards. This erosion process is usually not a conscious act, but rather a gradual process of daily adjustments made by the workers themselves. The standard represents their view of “how things are really done around here” and not the explicit quality goals often mandated by management.

The car manufacturers need to keep their standards high for competitive reasons. Not only do trucks provide better margins, but according to Business Week, “Trucks are a key to Detroit’s quest to lock in market-share gains against Japan. … Truck sales may help the Big Three continue their gains against Japan — but only if they avoid past mistakes.”

Detroit’s challenge is to maximize quantity without sacrificing quality. In the short term, tough choices have to be made between building current market share and building a long-term reputation of quality. If building market share is a priority, giving explicit reasons and time tables about its negative impact on improvement activities in the short term may help protect against a long-term erosion in standards.