Today’s workforce represents a broad range of age groups. As a result of college internships, modern healthcare, antidiscrimination laws, and a plethora of lifestyle choices, the workplace is a convergence of people aged anywhere from 18 to 78, spanning four generations. This multigenerational workforce has tremendous systemic implications for leaders and their organizations. It presents challenges in managing the inevitable tensions arising from conflicting values and divergent perspectives, but also offers tremendous, untapped, complementary potential within the dissonant mix.

This article will explore the manifestation of generations in the workplace through the lens of a compelling model that considers generational “personas” throughout history and their cyclical relationship to each other. By examining the dynamics of the generations present in today’s organizations, including their collective strengths, limitations, and the generational biases they may hold, I hope to provide a fresh perspective on workplace conflicts, leadership blind spots, and the promise of intergenerational collaboration as a means to elevate organizational potential and future success.

TEAM TIP

As a group, use this article to evaluate your work relationships from a generational perspective. Do you find evidence of generational biases? Where and why? How can you combat negative stereotypes about the different cohorts? Does your organization enlist Boomers in mentoring Xers and Millennials in assuming leadership roles as the older generation heads toward retirement? If not, what steps could be taken?

Generations Theory

There are a number of research studies, articles, and books that describe the historical and socioeconomic trends that influence the traits of different generations. Foremost, however, is the research conducted by historians William Strauss and Neil Howe. Strauss and Howe’s seminal book, Generations: A History of America’s Future 1584 to 2069 (William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1991), examines the socioeconomic, cultural, and political conditions throughout American history and their impact on the formation of distinct generational characterizations, or “peer personalities.” A number of factors influence peer personalities, including the cultural norms for childrearing at the time, the perception of the world as members of the generation start to come of age, and the common experiences the generation encounters as it enters the adult world. In this way, a generational identity is formed that has distinct effects on the environment and, in turn, younger generations.

GENERATIONAL CYCLES

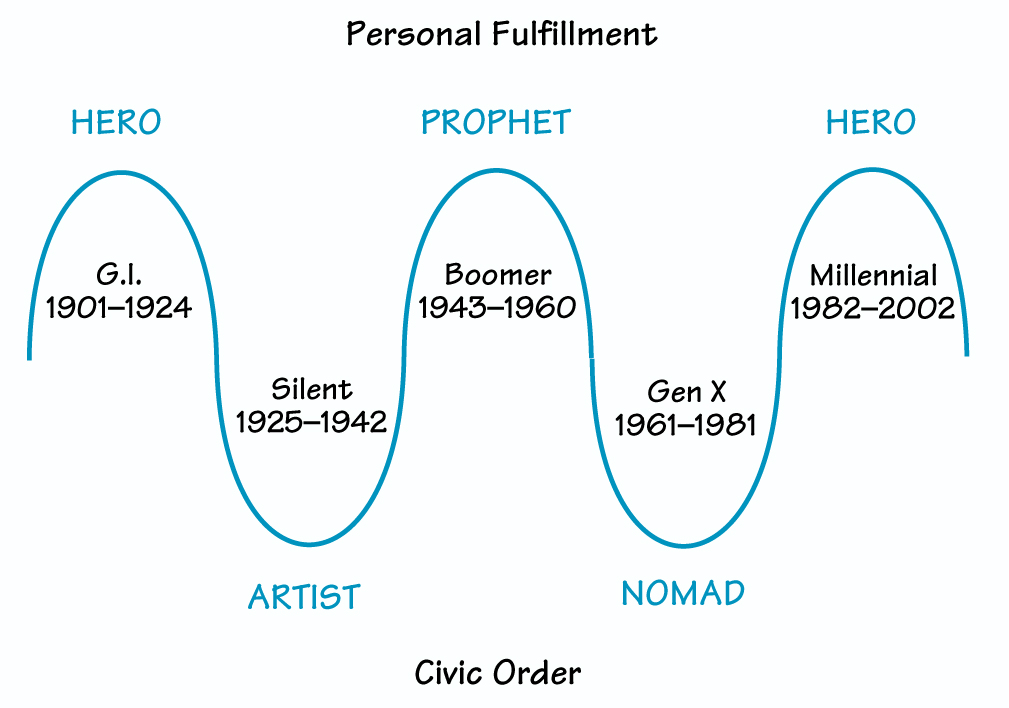

After examining the history of the United States, Strauss and Howe maintain that each generation falls into one of four archetypes that repeat in a fixed, cyclical pattern, roughly every 80 years. The archetypes are Prophet, Nomad, Hero, and Artist (see “Generational Archetypes”). At a macro level, generations in each archetype tend to share similar experiences and have comparable impacts on the culture as they move through the four stages of maturity: childhood, young adult, midlife leader, and elder. For instance, Prophet generations tend to be indulged as children, immersed in spiritual self-discovery as young adults, preoccupied with moral principles as midlife leaders, and vision-driven as elders. Artist generations, on the other hand, are inclined to be smothered and overprotected as children, sensitive and conforming as young adults, tolerant and indecisive as midlife leaders, and empathetic to younger generations as elders. These archetypal tendencies impact the culture as they surface in social activism, leadership styles, organizational priorities, and national policy.

GENERATIONAL ARCHETYPES

Prophet Archetype

(example, Baby Boom Generation): Wants to transform the world, not simply maintain what was handed to them. Remembered most for their coming-of-age passion, their key endowments are in the realm of vision, values, and religion. Prophet generations of the past have been principled moralists, proponents of human sacrifice, and wagers of righteous wars. As children, they are nurtured and indulged during times of prosperity and hope; as young adults, they self-righteously challenge the moral fortitude of elder-built institutions, initiating a spiritual awakening; as mid-lifers they become judgmental and fixated on their moral principles and intractable convictions; as elders, they provide the vision to resolve the moral dilemmas of the day, making way for the secular goals of the young.

Nomad Archetype

(example, X Generation): Relies on cunning and practical skills for survival. Remembered most for their midlife years of practical, hands-on leadership, with key endowments in the realm of liberty, survival, and honor. As children, they are under-protected, often during a time of social convulsion and adult self-discovery; as young adults, they are alienated and shameless free agents, independent and realistic during a time of social turmoil; as mid-lifers, they are pragmatic, resolute, and tough, defending society and safeguarding the interests of the young during social crisis; as elders, they are exhausted, favoring survival and simplicity during safe and optimistic times.

Hero Archetype

(examples, G. I. and Millennial Generations): First fights for, then rebuilds, the secular order. Known for their coming-of-age triumphs (usually wars) and hubristic elder accomplishments, their chief endowments are in the realm of community, affluence, and technology. Past Hero generations have been grand builders of institutions and proponents of economic prosperity. They have maintained a reputation for civic energy well into old age. As children, they are protected and nurtured in a pessimistic and insecure environment; as young adults, they collectively challenge the political failure of elder-led crusades, galvanizing a secular crisis; as mid-lifers, they establish a positive and powerful ethic of social discipline to rebuild order; as elders, they push for larger and more grandiose secular constructions, bringing on the spiritual goals of the young.

Artist Archetype

(examples, Silent and the very young Homeland Generations): Quietly seeks to refine and harmonize social forces. Known for flexible, consensus-building leadership during their mid-life years, their chief endowments are in the realm of pluralism, expertise, and due process. They have been advocates of fairness and inclusion, are competent social technicians, and are highly credentialed. As children, they are overprotected during a time of political chaos and adult self-sacrifice; as young adults, they are conformists, lending their expertise to an era of growing social calm; as mid-lifers, they are indecisive and strive to refine processes to improve society while seeking to calm the flaring passions of the young; as elders, they become empathetic to the changes of the day and shun the old in favor of complexity and sensitivity.

Each generation overcorrects what it perceives to be the excesses of its predecessors. Accordingly, at any given time in history, each archetype’s collective reaction to the social climate of the times, together with its related influence on those times, creates a predictable and repetitive pattern of both generational personas and social phases (see “Generational Cycles,” p. 2). In essence, the cyclical recurrence of the four archetypes serves as a natural balancing process that manages the inevitable tension between two powerful and polar social forces — civic order and personal fulfillment. The effect of this loop is to impel the evolution of society forward in a spiral process not unlike the seasonal changes of nature: from summer’s heat to autumn’s harvest, followed by the cold of winter and the eventual germination of spring (for more information, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strauss_and_ Howe).

The Strauss and Howe model asserts the possibility that, at some level, we as a society have been here before. If history repeats itself, it does so because of the complex tensions and ongoing negotiations between the equally important human precepts of order and freedom, secular stability and spiritual fulfillment, communal good and individual rights. If our relationship to these core principles is informed by our generational experience, then many of our own mental models, biases, and behaviors will, to some degree, be tied to our place in time and reinforced by our peers. In addition, this model suggests that each generation has a crucial place in this evolutionary cycle, a particular contribution to make, one that may not be obvious to those blinded by their generation’s limited perspective. Generational theory and the data that supports it can expose the intergenerational biases that covertly occupy our workplace and illuminate the cooperative potential that exists in our current place in time, as we confront the future and strive to tackle the looming issues of our day.

With the implications of this theory in mind, let’s take a closer look at the four generations currently in the workforce.

The Generations of Today’s Workplace

The landscape in today’s workplace includes four different generations, each with a distinct set of defining experiences and attributes — both strengths and limitations — that characterize its overall leadership and cultural impact. There are of course individual exceptions to and variations from this big-picture model; nonetheless, I invite you to consider how your generation’s collective characteristics might, in some respects, be true for you, and whether that insight can inform the way you perceive and interact with others.

There are differing opinions on the birth years that define the generations; however, the dates given below reflect those published by Strauss and Howe, who present strong justification and sociological relevance for the ranges they cite.

Silent Generation (Artist Archetype) Born: 1925–1942

The Silent Generation still maintains a small presence in the workforce, although most make up today’s senior citizen demographic. Silents were children during the Great Depression and World War II. Largely overprotected by their parents, they were quiet and obedient, living with food rationing and the daily fear of bad news, be it a foreclosure, a layoff, or a war casualty. Outflanked in both numbers and stature on one end by the great sacrificing war heroes of the older G. I. generation, and on the other end by the indulged new generation of postwar “victory babies,” Silents were expected to do little more than tow the line of progress. As a generation, they married early, had children quickly, and subsequently endured the highest divorce rate in history. Nonetheless, many Silents went from penniless children to affluent elders. Committed to public interest advocacy, the Silent Generation produced Civil Rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, and while they still hold approximately 25 percent of national leadership positions in state and federal government, they have yet to produce a U. S. president.

As leaders, Silents tend to focus on process and protocol, endlessly refining approaches, mediating differences, and seeking elegant ways to build compromise. They were the fine-tuning engineers who put Neil Armstrong on the moon, the expert proponents of Total Quality Management, and the tolerant designers of integrated school systems. Often viewed by other generations as timid, unconfident, and ineffective, the Silent generation nonetheless exhibits the kind of modesty and poise that serves as a quiet reminder of the enduring virtues of respectful process, genteel behavior, and inclusive conduct, standards that will likely have a crucial role in our global future.

Baby Boom Generation (Prophet Archetype) Born: 1943–1960

Both in size and prowess, the Baby Boom is the dominant generation of our time. Boomers grew up in an era of indulgent parenting and prosperous times. As “Leave It to Beaver” youth, they were expected to follow in the G. I.s’ footsteps and build the next golden age. Confident and filled with the potential of creative independence, Boomers have not, however, embraced the grand civic destiny that their parents envisioned for them. Rather, the “Me” generation has rebelled against authority, resisted conforming to the status quo, and taken the notions of individualism and generational identity to a new level. From the “consciousness revolution” of the 1960s and 1970s, to the “yuppies” of the 1980s, to the polarized culture wars of today, the Baby Boomers as a generation are known for their fixation on self, youth, individual expression, and intractable moral convictions about right and wrong. Communal and well-networked, their collective passions and values have become a mainstay in our culture and are squarely reflected in our nation’s consumer, corporate, and leadership trends.

Baby Boomers inhabit the most powerful leadership positions throughout the United States — including the presidency — and hold much of the experiential, institutional, and political knowledge in the workplace. As leaders, Boomers tend to be vision- and mission-focused, sometimes to the point of being unwilling to move ahead without a highly principled course of action in place. As transformers, they frequently seek to reorganize, redefine, or overhaul their organizations. In every sector, Boomers often want to make their mark through an improvement, distinction, or change. Many lack the discipline, however, to see transitions through or are intolerant to the resistance that comes with change.

Often married to their work, Boomers have embraced the 24/7, driven, competitive work ethic and, as a result, tend to remain short-term focused — be it the end of the quarter, the budget cycle, or their term. For many, this pressure-driven mentality can trigger reactive decision-making, trumping more systemic, long-term strategic thinking. As they retire, the Baby Boom generation will enter their Elderhood — the phase of life during which past Prophet generations have made their most potent leadership contributions.

X Generation (Nomad Archetype) Born: 1961–1981

Xers came of age in the 1970s and 1980s, when the prevailing message of the day was to grow up fast. Primarily children to working, in many cases divorced parents from the Silent generation, Xers were deemed “latch-key kids” for the adult-centric childrearing practices that left many youngsters largely unsupervised by today’s standards. Self-reliant and street-wise at an early age, leading-edge Xers graduated from college in greater debt than any previous generation. Many were forced to take low-level, low-paying “McJobs” as they sought entry into the Boomer dominated, “leaner and meaner,” competitive marketplace. Criticized as “slackers” by the media, Xers learned to rely on their finely honed survival skills and comfort with the fast-paced, changing landscape of the Information Age. Independent, pragmatic, and technologically resourceful, Xers are currently some of the most sought-after employees in the workforce.

As casualties of the era of corporate downsizing, Xers tend to be skeptical of promises and grand policy visions and, hence, demonstrate little organizational loyalty. Their pragmatism leads them to measure their success on their most recent accomplishments or acquired skills versus contributions to a greater vision. There are relatively few Xers in leadership positions today, with the exception of the high-tech industry and entrepreneurial ventures. Xers tend to be highly pragmatic, no-nonsense, action-oriented, good at learning on the fly, and opportunistic (which can appear to Boomers as unprincipled). They can be good team collaborators when not bogged down with idealistic debates and tend to be proficient with deliverables and project management. Accustomed to fending for themselves, most Xers prefer to focus on their own sphere of influence — family and friends. Many aren’t willing to embrace the 24/7 work ethic, and often put work-life balance over income and career advancement. Xers have little awareness of their greater collective force as a generation, and as such often lack the networks and connections needed to influence institutions and the power to make beneficial changes.

Most organizations have failed to recognize the need to prepare Xers to take the lead in the coming generational shift. Lacking much formal leadership training or mentoring, Xers often struggle with the subtle nuances of leadership and can appear draconian when making decisions. History, however, holds a promise to leaders who strive to earn the trust of this talented generation. The X generation’s collective life skills and deep devotion to the future welfare of their children will arouse for many the courage to commit to meaningful challenges and the endurance to see through hard times.

Millennial (Y) Generation (Hero Archetype) Born: 1982–2002

The oldest Millennials (or “Gen Y,” as some call them) are just now entering the workforce. They have a different set of childhood experiences than the other three generations, and while they are still quite young, they are nonetheless making themselves known. Largely children of Baby Boomers, Millennials were born at a time when there was a tremendous social investment in children and childhood programming. From “baby on board” stickers announcing their presence to fully scheduled days being bustled from one adult-led activity to another, Millennials have led highly protected and programmed lives. They were indoctrinated into the paradigm of standardized testing and are byproducts of the self-esteem movement that infiltrated school curricula in the 1990s, proclaiming all children to be “winners.” As such, Millennials are accustomed to frequent praise for all activities and accomplishments. The digital communication age is their birth right, and they are technologically superior to older generations, including Xers. Because of the on demand capability to access information, many Millennials have a global understanding of the world and value diverse cultures, experiences, and environments. They tend to be accepting of differences and measure people on the quality of their talent and output, rather than on physical or cultural characteristics (for additional details, see Managing Generation Y by Carolyn A. Martin and Bruce Tulgan, HRD Press, 2001).

As they enter the workplace, Millennials bring enthusiasm along with a sense of entitlement. Many expect career-track guidance, supervisory oversight, and regular, appreciative acknowledgement. They are confident, bold, and willing to speak up for what they want. As employees, they will seek environments that address their needs for structure and adequate direction, balance between personal and professional pursuits, up-to-date technology, and a socially conscious mission.

The challenge of this generation lies in their heavy reliance on external stimuli and direction from above. They tend to lack the self-reliant skills of the Xers, and have little internal aptitude to process and effectively learn from failure. Given the demographic reality of the workforce over the next 20 years — according to the American Society of Training and Development, 76 million retiring and 46 million entering — skilled Millennials will have their choice of employers. Optimistic, technologically masterful, and civically focused, the Millennial generation promises to be a competent and highly productive workforce; however, they will need sufficient oversight, on-the-job training, and clear direction from older leaders—and they have the demographic power to demand it!

BOOMER AND XER BIASES

Intergenerational Conflicts in the Workplace

When considering the diverse perspectives, values, and competencies that exist in our multigenerational workforce, it becomes easier to glimpse the many possibilities for collaboration and cooperation that may be present. But collaboration of this magnitude will require some changes in the status quo. Before we can move into a productive future of shared vision for an intergenerational workplace, the two groups with the greatest leadership leverage— Boomers and Xers — must each take stock of the biases and mental models they hold in order to discover their intergenerational synergy.

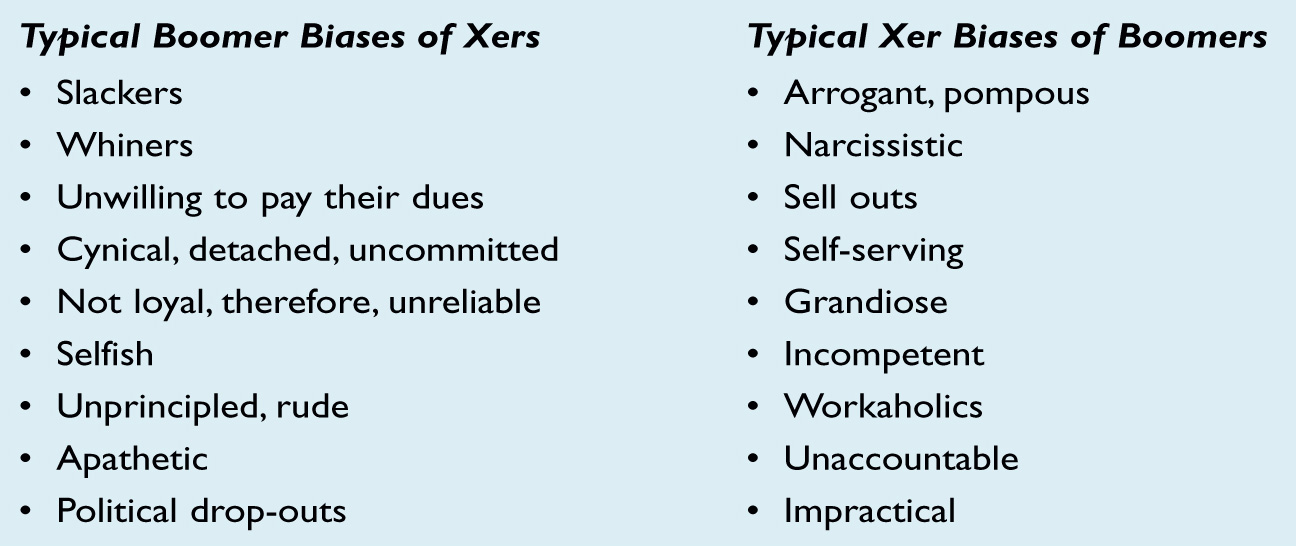

Generational Biases. Intergenerational conflicts arise primarily from the biases that each peer group has about the others. Individually, we may be unaware of the insidiousness of these biases. Left unacknowledged, they have a profound effect on our ability to recognize areas of compatibility and work toward common purposes. Focusing on the Boom and X generations, “Boomer and Xer Biases” gives examples of commonly held biases each has of the other.

In essence, the biases each group has of the other reflect a generation centric perspective, one that fuels a belief that “my way is the right way” and “your way doesn’t measure up to my values.” These biases are further substantiated by peer reinforcement, as members of each generation talk among themselves about the way they see others. This dynamic interferes with the capacity of individuals to listen to and respect the perspectives and contributions of others, thereby blocking meaningful collaboration in teams, supervisory relationships, and between colleagues. Conducting candid discussions in mixed generational groups about the biases that exist can be an effective way to disarm the negative impacts they may have on collaborative thinking. Exposing biases can also illuminate important social issues that need to be addressed.

Generational Mental Models and Blind Spots. Our generational perspective contributes to the mental models we hold about ourselves, the world, and the way things “should” be. These beliefs create blind spots that can become our undoing as we pursue our values and seek to accomplish our goals. Likewise, they can have a powerful effect on our culture.

The generational mental models held by the Baby Boomers are clouded by the assumption that others see the world as they do. This is a typical perspective of powerful and dominant generations who, having had such a massive impact on the culture, are often unaware of how that impact is experienced by other generations. A prominent mental model shared by many Boomers is the tendency to view the rebellious era of their youth as their generation’s greatest contribution. This belief is reflected by Boomer obsessions with 1960s nostalgia, retro fashion, classic rock, and youthful enhancements like Botox and Viagra. There is a sense in which Boomers still view themselves as children, rather than the adult leaders and authorities that they are.

This self-immersion in the glories of the past — in which many Boomers “Questioned Authority” and waged adolescent wars against “The Man” — stands in stark contrast to the fact that, today, they are the establishment. The systemic impact of this reality is profound: If the collective attention of the leading generation appears to be focused on youthful notions of a time long gone, then who is attending to the present reality and the responsibilities of leading for the future? Certainly some individuals are doing so, but at the macro level, from the perspective of younger and older generations looking on, Boomers have all the positional and cultural power to affect change for the future. Yet as a generation, they appear fixated on preserving their youth, focused on competitive one-upmanship, mired in intractable positions, and inattentive to what is required for long-term sustainability. Such a perspective has eroded trust, respect, and confidence in Boomer leadership and colors the mental models of younger generations.

Accordingly, the mental models held by the X Generation are clouded by distrust and pessimism. As a less dominant and younger generation, they are naturally attuned to hypocrisy, and use any evidence of it to justify their cynicism and detachment. Disconnected from their own collective power, a mental model common to many Xers is the perception of themselves as loners who are on their own and have little in common with those outside of their intimate circles. As a result, most Xers see no point to activism and the spurring of institutional change. Rather, they prefer private solutions to public issues and seek to improve the quality of life within their own small sphere of influence. Practical and perhaps initially effective, the systemic impact of this perspective has its dysfunctional qualities. If this generation indeed has a deep commitment to family and the future of their children, yet remains apathetic about influencing the vision and direction of the institutions that affect them (employers, public schools, national agenda), then how will that bode for the future of their children? If Xers continue to opt out, they will in effect be leaving that future to chance.

Thinking Systemically About Workforce Demographics: A Case Study

Five years ago, the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) at the U. S. Food and Drug Administration surveyed its workforce and discovered that most employees had been there for more than 25 or less than 5 years, and that the Center would be facing large numbers of retirements in the near future. This data impelled CFSAN leadership to prioritize the task of preparing their organization for the future. A high-level task force was appointed to study the situation and come up with concrete recommendations for a credible succession plan. After a year of investigation and with strong commitment from the entire organization, CFSAN created a Leadership Legacy Steering Committee. This group became responsible for designing a leadership development program that accounted for the needed skill sets and demographic reality of the Center’s workforce.

Rather than starting at the top (as is more typical), CFSAN began training first-line supervisors in the art and skills of leading people. Not only did this decision address the greatest need, it also signaled to more junior employees that they mattered and that this initiative was not just another perk for top management. As well as a solid training component, the program features mentoring and shadowing opportunities with senior leaders, promoting deeper intergenerational relationships and increasing the transfer of vital institutional knowledge. In addition, participants have opportunities for developmental assignments in different units and special team projects, both of which enhance collaborative relationships across Center departments.

The second level, for middle managers, which began last year, is aimed at emerging leaders who demonstrate the savvy and potential to lead at an organizational level. The third level focuses on senior managers and will emphasize strategic leadership skills.

CFSAN is accomplishing this effort despite severe budget cuts and increasing workloads. The organization continues to be led by Baby Boomer administrators who have committed to securing the future of the organization. They recognize that the best hope for ongoing success will come from younger employees who are motivated to take on larger responsibilities and feel empowered by the earnest attention paid to their development.

History’s Promise: Intergenerational Collaboration?

Historical trends show that major secular crises recur every 80 years or so, the last one beginning with the Great Depression in 1928. The leadership combination of an elder Prophet generation, providing vision and a strong moral compass, together with a mid-life Nomad generation, fortified with sturdy persistence and expertise, was ideally suited for enduring the crisis and forging a new order. The Prophet and Nomad generations of that time were able to face the extreme difficulty through collaboration and generational cooperation. Their leaders found the courage to tell the truth, call forth needed sacrifice, and provide the hope that led the nation through the ordeal.

The challenges that face the nation’s institutions and communities today are deeply complex. No single generation can adequately address these issues without the cooperation and contributions of the others. The best hope for the future of our organizations and our culture rests on our capacity to form a shared vision that encompasses the best of what each generation values and has to offer. Whether Boomers and Xers can overcome the self-serving biases and limiting mental models that keep the two generations from collaborating for the future is unknown. It may require that external conditions worsen so that the stakes become higher. And perhaps the young Millennials — in seeking clear direction and oversight from leadership — will call the others to task, necessitating Boomers and Xers to come together to effectively lead this emboldened and demographically powerful workforce.

We have seen the systemic opportunities that can come from collaboration in communities, businesses, government offices, and nonprofits. By seeking to build the intergenerational connections that will lead to shared understanding, knowledge, and vision, we can elevate the potential of our organizations by harnessing the natural balancing forces inherent within the generational mix. This process, however, starts with a leader’s willingness to ask important questions about the future, questions that seek to understand the complexity and truth arising from diverse perspectives. In this way, the path forward will be much clearer and the solutions more promising.

Deborah Gilburg is a principle of Gilburg Leadership Institute, a leadership development firm specializing in generational dynamics and organizational succession planning. For more information, visit www.gilburgleadership.com. Deb will be presenting a concurrent session at this year’s Pegasus Conference.

NEXT STEPS

- 1. Start to look vertically at your employees, in your team, department, or organization. For example, consider the age, experience, and institutional longevity that exist at entry level, mid-level, and senior-level management.

- Take time to collect concrete data about the needs of employees and the organization, now and in the future. For example, get facts about potential knowledge loss from retirement, skill sets in younger employees, and key motivators of those in a position to advance in and enter the organization.

- Pay attention to generational diversity issues so you can address the biases and create credible programs and incentives. For example, make sure that you connect the information about what matters to your employees to the organizational goals for the future, and address the skill sets needed in training and development programs.

- Encourage intergenerational relationships by creating opportunities for project collaboration, focused conversation, and mentoring. Consider taking time to identify areas of strength, challenge, and compatibility. For example, implement a valid mentoring program in recognition that it takes leaders to develop leaders. This might mean creating a program to train mentors first!