What would it mean if we knew how to successfully engage with the unknown, the uncomfortable, the unprecedented so that our organizations and communities could thrive?

Many of our current cultural stories seem to reinforce a belief that challenge and conflict lead to collapsing systems. Stories of breakdown are everywhere — a struggling economy, political polarization, declining high school graduation rates. Yet even as these systems falter, new beginnings are all around us. The more we look for stories of innovations launched and challenges overcome, the more visible they become.

When we allow ourselves to look through this lens, we see that a renewal is under way, a modern renaissance fueled by the passion and commitment of many who have dared to pursue a dream. In communities, organizations, industries, and other social systems, new ways of living and working are flourishing. For example, many consider journalism to be an industry in decline. But even as traditional forms of journalism are dying — because they aren’t serving us well — I see signs of rebirth every day. Bold experiments are underway. Spot.us uses “crowdfunding,” in which community members pool money to support investigative reporting. News Trust, which rates the news for accuracy, fairness, and other criteria, is drawing increasing readership and participation to its site. Similar innovations are arising in other areas, ranging from healthcare to politics.

Given these parallel dynamics of collapse and rebirth, what can we do to help the systems of which we are part move toward productivity and resilience?

For more than 50 years, experiments in organizations and communities and across social systems have shaped practices for “whole systems change” — methods for engaging the diverse people of a system in ways that lead to unexpected breakthroughs. In 1992, Margaret Wheatley’s groundbreaking Leadership and the New Science contributed to theory by connecting our changing understanding of science to human systems. As the current generation of whole systems change practitioners mix and match methods such as Open Space Technology, The World Café, Future Search, and Appreciative Inquiry, many of us have been seeking a deeper understanding of the patterns that make these practices work.

My quest to unlock the mystery of what is involved in changing whole systems began in the late 1980s. I thought that understanding how change works was key to creating a world that works for all. I still do. I started noticing shifts in how change occurs when using whole systems change practices. See “Traditional and Emerging Ideas About Change” for examples.

Born from my own practice, my interactions with friends and colleagues, and my immersion in what science has taught us about chaos, complexity, and networks, I noticed a pattern of change through the lens of emergence — increasingly complex order self-organizing out of disorder. What follows describes that pattern, along with questions, principles, and practices for successfully engaging with upheaval.

The Nature of Emergence

Emergence is nature’s way of changing. We see it all the time in its cousin, emergencies. What happens?

A disturbance interrupts ordinary life. In addition to natural responses, like grief or fear or anger, people differentiate — take on different tasks. For example, in an earthquake, while many are immobilized, some care for the injured, others look for food and water, a few care for the animals. Someone creates a “find your loved ones” site on the Internet. A few blaze the trails and others follow. They see what’s needed and bring their unique gifts to the situation. A new order begins to arise.

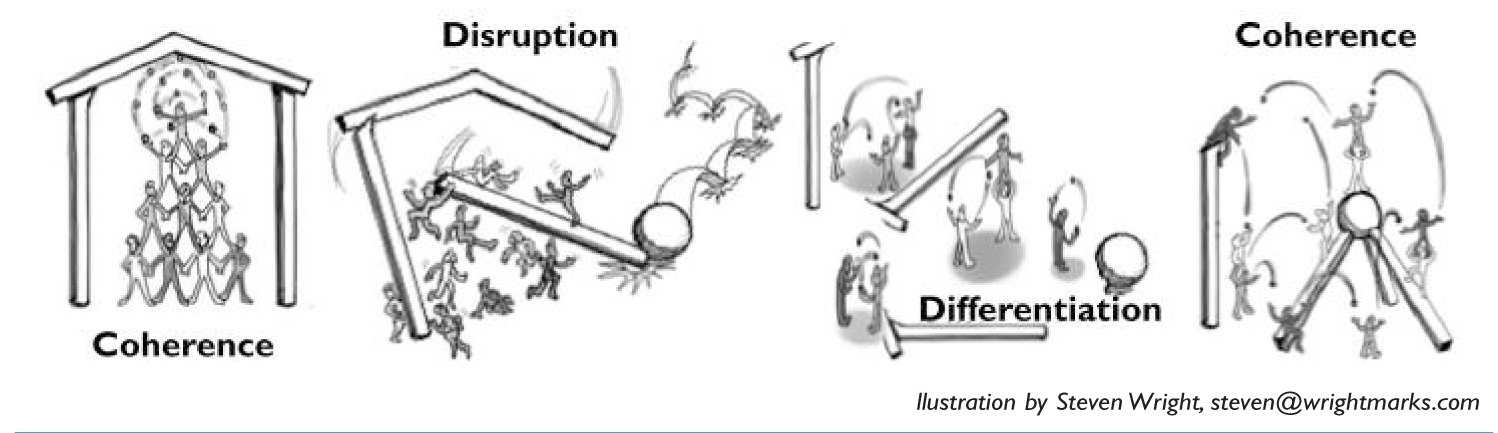

This pattern of change flows as follows:

- Disruption breaks apart the status quo.

- The system differentiates, surfacing innovations and distinctions among its parts.

- As different parts interact, a new, more complex coherence arises.

(See “A Pattern of Change.”)

A PATTERN OF CHANGE

In journalism, cracks began to appear in the 1990s as newspaper readership declined. This disruption was generally correlated with the rise of the Internet. Worse, advertisers, who provide a principle source of revenue for journalism, started to leave. When the economy came to the precipice in 2008, the decline became an avalanche (Johnny Ryan, Newspaper circulation decline).

With the ability for anyone to publish made possible through increasingly sophisticated online tools, the assumptions about what journalism is and how it is done are in flux. A myriad of experiments are testing those assumptions — the relationship between journalist and audience, the economic model, even the purpose of journalism itself. These experiments shed light on what to conserve from traditional journalism that still serves us well and what to embrace that wasn’t possible before. Journalism is differentiating into its elemental nature, helping us understand new ways in which news and information is created, distributed, and digested.

While a new coherence has not yet arisen and likely won’t for a while, we do have clues. We know it is more of a conversation than a lecture. It still is about making sense of our complex world so that we can make wise individual and collective decisions. And it calls for a broad-based digital literacy movement, similar to the literacy movement sparked by the coming of age of newspapers that served the formation of democracy in the U. S.

People often speak of a magical quality to emergence, in part, because we can’t predetermine specific outcomes. Emergence can’t be manufactured. It often arises by drawing from individual and collective intuition — instinctive and unconscious knowing or sensing without deduction, reasoning, or using rational processes. It can be fueled by strong emotions — excitement, longing, anger, fear, grief. And it rarely follows a logical, orderly path. It feels much more like a leap of faith.

Emergence is always happening. If we don’t work with it, it will work us over. In human systems, it often shows itself when strong emotions are ignored or suppressed for too long. While emergence is natural, we don’t always experience it as positive. Erupting volcanoes, crashing meteorites, and wars have brought emergent change. Yet even wars can leave exciting offspring of novel, higher-order systems. The League of Nations and United Nations were unprecedented social innovations from their respective world wars. New species or cultures fill the void left by those made extinct.

Emergence seems disorderly because we can’t discern meaningful patterns, just unpredictable interactions that make no sense. But order is accessible when diverse people facing intractable challenges uncover and implement ideas that none could have predicted or accomplished on their own. Emergence can’t be forced. It can, however, be fostered.

Why Does Engaging Emergence Matter?

Emergence isn’t just a metaphor for what we are experiencing. Complexity increases as more diversity, connectivity, interdependence, or interactions become part of a system. The disruptive shifts occurring in our current systems are signs that these characteristics are on the rise.

Today’s unprecedented conditions could lead to chaos and collapse, but they also contain the seeds of renewal. We can choose to face our seemingly intractable challenges by coalescing into a vibrant, inclusive society characterized by creative interactions among diverse people. In many ways, this path is counterintuitive. It breaks with traditional thinking about change, including the ideas that it occurs top-down and that it follows an orderly plan, one step at a time.

We don’t control emergence. Nor can we fully predict how it arises. It can be violent, overwhelming. Yet we can engage it, confident that unexpected and valuable breakthroughs can occur.

Benefits of Engaging Emergence

Although specific outcomes from emergence are unpredictable, by engaging with it some benefits are foreseeable. To illustrate these benefits, I draw from Journalism That Matters, an initiative that convenes conversations among the diverse people who are shaping the emerging news and information ecosystem.

Individually, we are stretched and refreshed. We feel more courageous and inspired to pursue what matters to us. With a myriad of new ideas and confident of the support of mentors, collaborators, and fans, we act. At an early Journalism That Matters gathering, a recent college graduate arrived with the seed of an idea: putting a human face on international reporting for U. S. audiences. At the meeting, she found support for the idea. Deeply experienced people coached her and gave her entrée to their contacts. Today, the Common Language Project is thriving, having received multiple awards.

New and unlikely partnerships form. When we connect with people whom we don’t normally meet, sparks may fly. Creative conditions make room for our differences, fostering lively and productive interactions.

A reluctant veteran investigative reporter was teamed with a young digital journalist. They created a multimedia website for a story based on a two-year investigation. Not only did the community embrace the story, but the veteran is pursuing additional interactive projects. And the digital journalist is learning how to do investigative reporting.

Breakthrough projects surface. Experiments are inspired by interactions among diverse people.

The Poynter Institute, an educational institution serving the mainstream media, was seeking new directions because its traditional constituency was shrinking. Because Poynter served as a cohost for a JTM gathering, a number of staff members participated in the event. They listened broadly and deeply to the diverse people present. An idea emerged that builds on who they are and takes them into new territory: supporting the training needs of entrepreneurial journalists.

Community is strengthened. We discover kindred spirits among a diverse mix of strangers. Lasting connections form, and a sense of relationship grows. We realize that we share an intention—a purpose or calling guided by some deeper source of wisdom. Knowing that our work serves not just ourselves but a larger whole increases our confidence to act.

As a community blogger who attended a JTM conference put it, “I’m no longer alone. I’ve discovered people asking similar questions, aspiring to a similar future for journalism. Now I have friends I can bounce ideas off of, knowing we share a common cause.”

The culture begins to change. With time and continued interaction, a new narrative of who we are takes shape.

When Journalism That Matters began, we hoped to discover new possibilities for a struggling field so that it could better serve democracy. As mainstream media, particularly newspapers, began failing, the work became more vital. We see an old story of journalism dying and provide a place for it to be mourned. We also see the glimmers of a new and vital story being born. In it, journalism is a conversation rather than a lecture. Stories inspire rather than discourage their audience. Journalism That Matters has become a vibrant and open conversational space where innovations emerge. New language, such as news ecosystem — the information exchange among the public, government, and institutions that can inform, inspire, engage, and activate — makes it easier to understand what’s changing. People say, “I didn’t know I could be effective without a big organization behind me. Now I do.”

These experiences show that working with emergence can create great initiatives, the energy to act, a sense of community, and a greater view of the whole — a collectively intelligent system at work.

As more people engage emergence, something fundamental changes about who we are, what we are doing, how we are with each other, and perhaps what it all means. In the process, we tear apart familiar and comfortable notions about how change works. We bring together unlikely bedfellows and re-imagine and re-create the organizations, communities, and social systems that serve us well.

Three Questions for Engaging Emergence

Three questions can help us think about how to work with change:

- How do we disrupt coherence compassionately?

- How do we engage disruption creatively?

- How do we renew coherence wisely?

Like all appreciative questions, these direct our attention toward possibilities and open us to exploration. They are posed as questions rather than statements to remind us that when the terrain is uncertain, focus and fluidity both support us to be nimble in our response.

You can use them as you might an affirmation. Just as affirmations help us attend to what we wish to create, these questions help us adapt to the specifics of our situation. We can connect our circumstances with the flow of change by prefacing each question with, “In this situation…”

These questions create temporary shelter for us to consider the challenges of a changing system. They help us experience and offer compassion in disruption, engage creatively with difference, and support both personal and collective renewal while potentially wise responses coalesce.

If you are familiar with Zen Buddhism, think of the questions as koans — paradoxical riddles or anecdotes that have no solution. They may — if you seek to understand them in an intuitive way and work with them in your life — provide flashes of insight into what’s going on and how to engage it.

Principles for Engaging Emergence

A principle is a fundamental assumption that guides further understanding or action. Principles help us make order out of chaos. They describe the landscape, enabling us to discern useful characteristics so that we can make useful choices. Principles support us in designing our initiatives, organizing our work and ourselves, determining what to do and how best to do it. For example, a commonly cited medical principle is “first, do no harm.” This fundamental understanding guides life-and-death decisions without prescribing a specific approach.

I derived the principles for engaging emergence listed below by connecting my understanding of whole systems change processes with what science tells us about the dynamics of emergence (see “Principles for Engaging Emergence”). In short, scientists frequently cite four dynamics of emergence:

- No one is in charge. No conductor is orchestrating orderly activity (ecosystems, economic systems, activity in a city).

- Simple rules engender complex behavior. Randomness becomes coherent as individuals, each following a few basic principles or assumptions, interact with their neighbors (birds flock; traffic flows).

- Feedback. Systems grow and self-regulate as the output from one interaction influences the next interaction. (We talk to a neighbor, who talks to a neighbor, and suddenly everyone in town knows a story.)

- Clustering. As we interact, feeding back to each other, like attracts like, bonding around a shared characteristic. (Small groups of women meeting in living rooms grow into the women’s movement.)So if emergence occurs through these dynamics, what are the implications for how we engage with it?

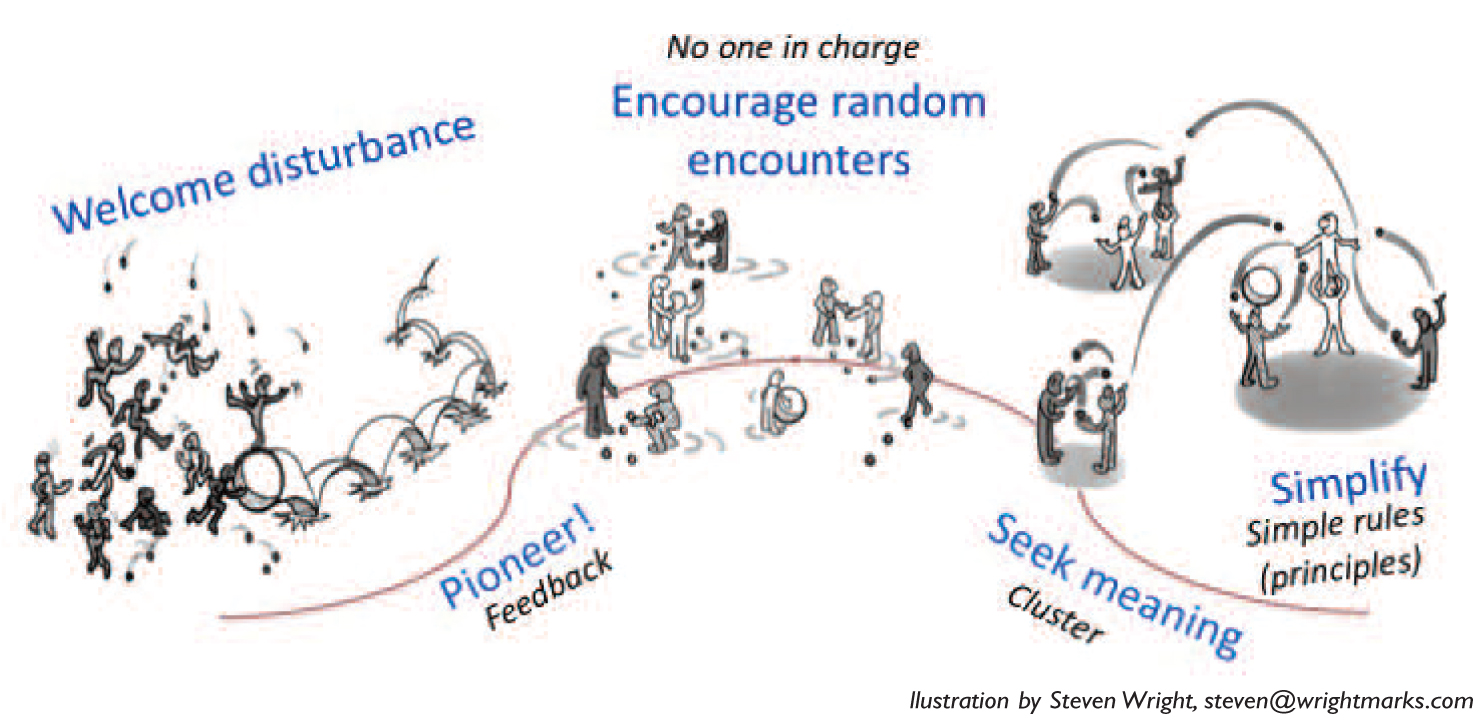

PRINCIPLES FOR ENGAGING EMERGENCE

These five principles are my answer to this question:

- Welcome disturbance. Disruption indicates that the normal behavior of a system has been interrupted. If we ignore the disturbance, chances are conditions will get worse. If we get curious about it, the disruption could lead to breakthroughs.

- Pioneer! Break habits by doing something different. Prepare and jump into the mystery, working with the feedback that comes.

- Encourage random encounters. Remember, no one is in charge. More accurately, we never know which interactions will catalyze innovation. Maximize interactions among diverse agents, knowing unexpected encounters will likely trigger a shift.

- Seek meaning. Meaning energizes us. As we discover mutuality in what is personally meaningful, we come together. Like clusters with like. Shared meaning draws us to common awareness and action. When shared meaning is central, we organize resilient, synergistic networks that serve our individual and collective needs.

- Simplify. Principles — simple rules — equip us to work with complexity. When principles break down and the situation grows chaotic, what is essential? What serves now? As answers coalesce, we become a more diverse, complex system around re-formed principles at the heart of the matter.

These principles help us work with the flow of emergence. Welcoming disturbance encourages us to begin, knowing all change starts with disruption. To support differentiation, pioneering guides us in thinking about what to do. Encouraging random encounters reminds us to consider who to involve. Seeking meaning provides a thread of coherence by helping us clarify why. And simplifying helps coherence emerge by guiding us to the how.

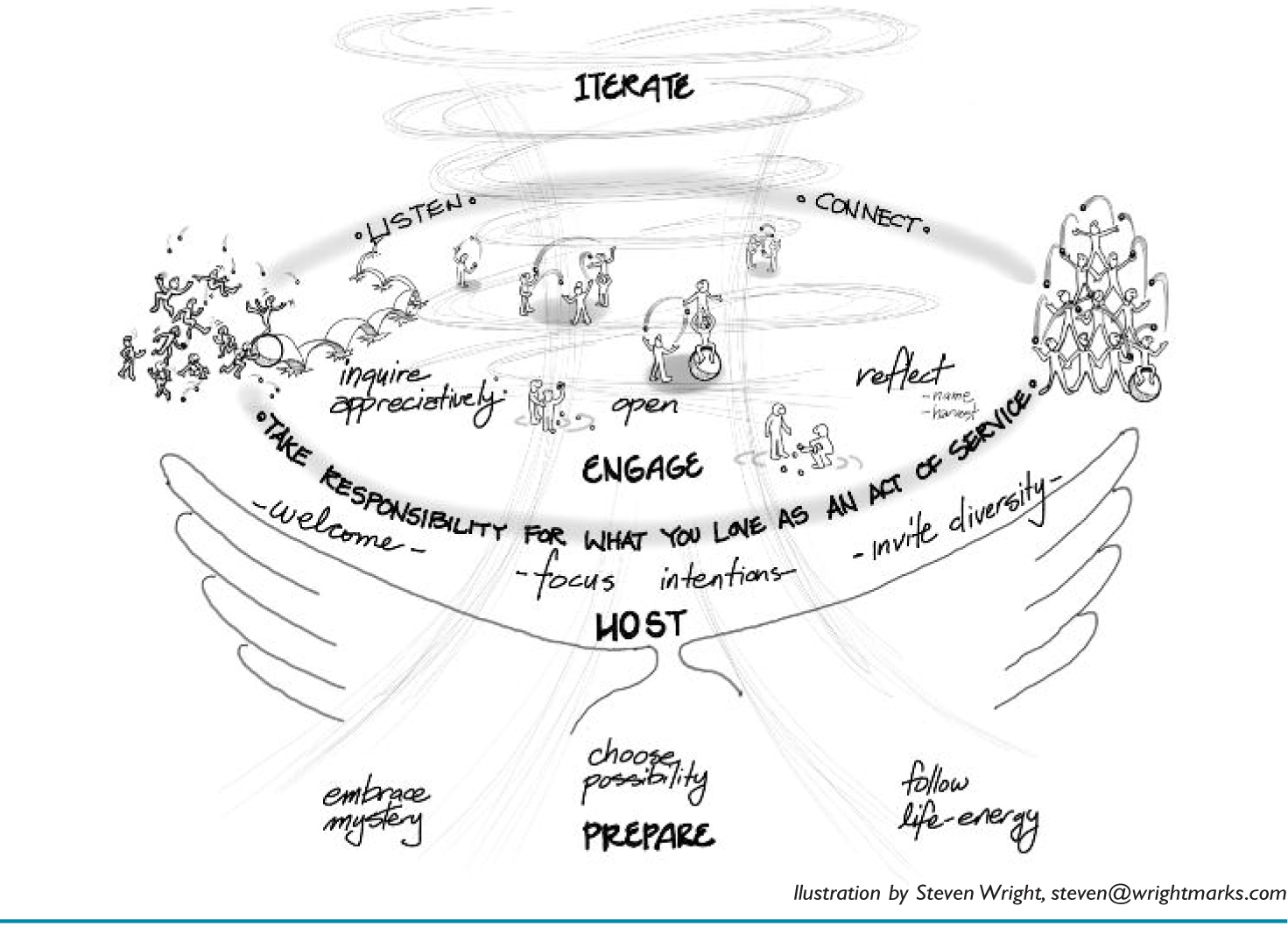

Practices for Engaging Emergence

If principles help us sort through what to do, practices guide us in how to do something. A practice is a skill honed through study and experimentation. The practices for engaging emergence are rooted in the skills of everyday conversation (see “Practices for Engaging Emergence”). As such, we all know something about them. They are our birthright. When issues are complex, stakes are high, and emotions are right below the surface, these practices help us engage with each other.

Because working with emergence has nothing A-to-B-to-C about it, no one right way exists to use these practices. They help us identify what to notice, what to explore, what to try. They are helpful hints for flying by the seat of our pants.

Just as scales prepare a musician and drills train an athlete, these practices equip us for the challenging conversations, the ones that involve disruption, difference, and the unknown. They are the conversational backbone for improvisation, enabling us to stay in the flow even if we don’t know the specific path we’re taking. Honing these conversational skills is a great way to engage emergence.

PRACTICES FOR ENGAGING EMERGENCE

I organize the practices into four groups:

Prepare to Engage Emergence

- Embrace mystery, choose possibility, and follow life-energy to cultivate a composed state of mind, alert to aliveness and potential. This enables us to face whatever shows up with equanimity or even delight.

Host Emergence

- Clarify intentions and welcome people. These are skills of being a good host. In exercising them, you create a “container” — a hospitable space for working with whatever arises. These practices are the yin and yang of hosting. One provides focus — clear direction and purpose. The other ensures fertile ground for relationships and connection.

- Invite diversity to encourage people to look beyond our habitual definitions of who and what makes up a system. Doing so prepares us for innovation by increasing the likelihood of productive connections among people with different beliefs and operating assumptions. Inviting diversity is one of the most time consuming, challenging, and critical activities of engaging emergence.

Engage

- Take responsibility for what you love as an act of service. This practice is a game-changing skill. It liberates our hearts, minds, and spirits. It calls us to notice what deeply matters to us and to put our unique gifts to use for ourselves, others, and the systems in which we live and work. The more this practice becomes our operating norm, the more innovation, joy, solidarity, generosity, and other qualities of well-being appear. The capacities for listening and connecting grow through this practice.

- Stepping in to inquire appreciatively is a second game-changing skill. The questions we ask determine the answers we uncover, shaping our experience, actions, and outcomes. Typically, the more positive the inquiry, the more life-affirming the outcome.

- Open yourself to the unknown. This practice is an act of faith. Once open, we can’t go back. It may be the most counter-cultural practice of them all, requiring the courage to be vulnerable.

- Reflect, name, and harvest — these can be sacred acts. They call forth that which previously didn’t exist. The arts — music, movement, visual arts, poetry, film — often enhance the effectiveness and reach of these practices.

Iterate: Do It Again . . . and Again

This practice reminds us of the never-ending nature of change. It takes time and perseverance to make its mark. Because our attention tends to get caught in our routines, iteration is the most elusive of the practices. Together, these practices form a system for acting, providing insight into what our role is, how we support others, and what we can do together.

What’s Possible Now?

Whenever we work with this pattern of emergent change, a turning point occurs as coherence arises. We experience ourselves as part of something larger. Perhaps our voice rises in harmony, a sweet blend of each and all. Or we overcome an obstacle because we used our different skills and abilities to accomplish something together that none of us could have done alone. We change through such experiences. The principles and practices I’ve described help us break through habits of separation that keep us fragmented. Our personal stories become a doorway into the universal.

Joel de Rosnay, author of The Symbiotic Man: A New Understanding of the Organization of Life and a Vision of the Future (McGraw-Hill, 2000), introduced a notion I find promising called the macroscope. Just as microscopes help us to see the infinitely small and telescopes help us to see the infinitely far, macroscopes help us to see the infinitely complex. Rather than a single instrument, they are a class of tools for sensing complex interconnections among information, ideas, people, and experiences. Maps, stories, art, media, or some combination could be used as macroscopic tools that would help us to see ourselves in a larger context. For example, consider the brilliant use of technology in a sports stadium. We are able to experience the game from many angles. At a glance, the scoreboard tells us the state of play. Cameras zoom in so that we can see the action not just on the field but also in the audience. Television dramatically extends the reach of the event. And a history of statistics available online lets both professional commentators and ordinary people put the activities in perspective. We can immerse ourselves in the experience and understand it from many perspectives. Imagine applying such thoughtfulness to making the state of the economy, education, or a war visible to us all.

Both microscopes and telescopes sparked tremendous innovation. Macroscopes have such potential today. As we appreciate our interconnectedness, our sense of who is our community expands. The conditions for greater trust and courage emerge. We act, knowing something about the collective assumptions and intentions we share. We become better equipped to work with upheaval and change.

Let us put these notions to work so that we fully engage with the nascent renaissance that is underway. Begin simply, wherever you are. I offer three suggestions:

- Be compassionate disrupters, asking possibility-oriented questions.

- Creatively engage, interacting with people outside our comfort zone.

- Support wise renewal, telling stories of upheaval turned to opportunity.

Peggy Holman has designed and hosted meetings for diverse groups handling complex issues since 1992, including the National Institute of Corrections, Microsoft, and the Associated Press Managing Editors. In the second edition of The Change Handbook, Peggy and co-authors Tom Devane and Steven Cady profile 61 change methods, including Appreciative Inquiry, Open Space Technology, and the World Café. Her new book, Engaging Emergence: Turning Upheaval into Opportunity (Berrett-Koehler, 2010), dives beneath these change methods to make visible deeper patterns, principles, and practices for change that can guide us through turbulent times.

NEXT STEPS

Ask Possibility-Oriented Questions. Be a champion for the appreciative. Especially in unlikely places, inquire into what is working, what is possible given what is happening.

Interact with People Outside Your Comfort Zone. Discover how stimulating it is to experience difference. In the process, you may develop some unexpected partnerships for bringing together diverse groups who care about the same issues.

Seek More Nuanced Perspectives That Help Us to See Ourselves in Context. If you are faced with Aversus-B choices, open up the exploration. Seek out other points of view. Discover the deeper meaning that connects deeply felt needs.

Tell Stories of Upheaval Turned to Opportunity. Help take to scale what is possible when you engage emergence. Share your experiences of working with disruption. Explore using tools that offer a macroscopic view to expand your reach.