The first part of this article, which appeared in the previous issue of The Systems Thinker (May 2010, Vol. 21 N. 4), introduced the “people-in-context” lens for understanding organizational interaction. It presented four common system contexts, or roles, that occur in all organizations: Top, Middle, Bottom, and Customer. In addition, Part I defined two principles. According to Principle 1, when we are blind to others’ contexts, we are likely to misunderstand their actions. Principle 2 shows that, when we are blind to our own contexts, we respond without awareness or choice. Part II of this article continues on to define principles 3 and 4, to examine a case study, and to examine implications for leadership development.

Groups in Context

We exist as members in organizational peer groups: in Top Executive groups, Middle Management and Staff groups, and Bottom groups. We also bring our personal bias to our group relationships, to our affinities and antipathies. When things go wrong in our groups, our tendency is to explain these difficulties in terms of personal issues: there is something wrong with you or me, or maybe we are just an unfortunate mix. And when our diagnoses are personal, so also are our usual remedies: fix, fire, rotate, separate, divorce, or recommend coaching or therapy for one or more parties.

In fact, many of the peer group breakdowns that occur are not personal at all; they become personal, but their roots lie in context blindness.

TEAM TIP

Principle 3: When We Are Blind to Our Peer Group’s Context

Principle 3: When we are blind to the contexts in which our peer groups are functioning, we are vulnerable to falling into dysfunctional scenarios that cause us personal stress, weaken if not end our relationships with our peers, and detract from the contributions our peer groups could be making to the system:

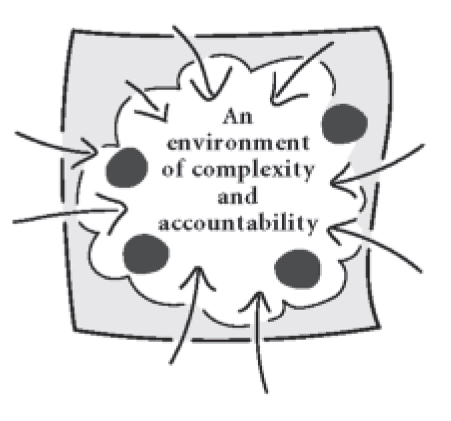

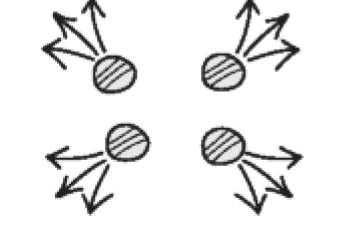

- Territorial Tops. Members of Top peer groups may see themselves as just people with a job to do, but they are more than that; they are a group existing in a context of complexity and accountability (“Four Persons in a Top Context”).

FOUR PERSONS IN A TOP CONTEXT

Without awareness and mastery of that context, they are vulnerable to falling into dysfunctional territoriality. The process goes something like this. As members of Top teams, we reflexively adapt to the complexity and accountability of our context by differentiating, with each of us handling our own areas of responsibility. Differentiation is an essential process; without it, we would not be able to cope with the complexity and responsibility of our situation. But then a familiar process unfolds; we harden in our differentiations. Differentiations become territories. Each of us becomes increasingly knowledgeable and responsible for our area and decreasingly knowledgeable and responsible for others’ areas. We develop a ‘‘mine’’ mentality. We become protective and defensive of our territory. And we face uncertainties about the form and future of the system: What kind of culture do we want to create? Do we want to expand in new directions or stick to our knitting? Are we going to take financial risks or play it cautiously?

These are complex questions with no textbook answers, yet we gradually polarize around fixed positions: the Riskers versus the Cautionaries; the Loose/Democratic System Builders versus the Bureaucratic/Authoritarian System Builders. Relationships fray. There are issues about who are the really important members of this team. Members feel they are not respected for their contributions. There are feelings about who is holding up their piece of the action. There are battles for control. Silos develop, sending mixed, confusing messages down through the system. There is redundant building up of resources in the silos; potential synergies across silos are blocked. Tensions among the Tops are high, and it all feels so personal.

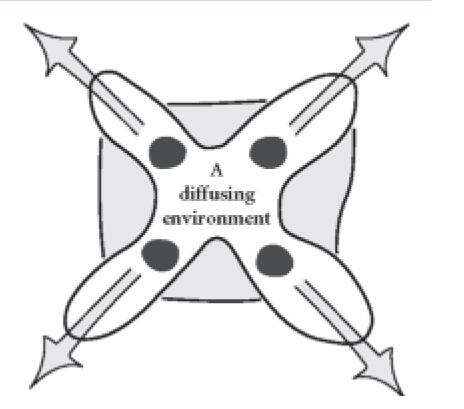

FOUR PERSONS IN A MIDDLE CONTEXT

- Fractionated Middles. Middle peer groups, whether first-line supervisors or middle managers or staff groups, may think of one another as just people and attribute their feelings about one another as simply reflections of one another’s personality, temperament, motives, values, and such. But Middle peer groups exist in a tearing context, one that draws them away from one another and out toward those individuals they are to supervise, lead, manage, coach, or service (“Four Persons in a Middle Context”).Dispersing is an adaptive response to that tearing context; that is what Middles are hired to do. But in time, we harden in our separateness. We develop an ‘‘I’’ mentality in which our separateness from one another predominates; our competitiveness with one another intensifies, as does our tendency to evaluate one another on relative surface issues: emotionality, manner of speech, skin color, gender, clothes we wear, and such. This fractionation of Middles isolates them, leaving them unsupported, without a peer group, able to be surprised, and often feeling undercut by actions taken by other Middles. It leaves the system uncoordinated, and it works against potential synergies among Middles or any collective influence by Middles.

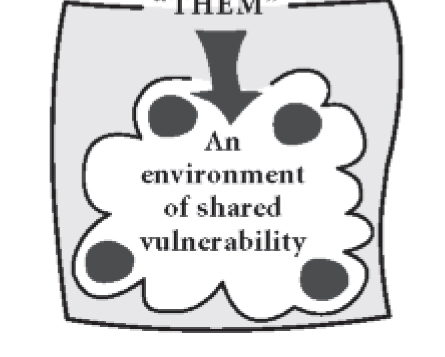

FOUR PERSONS IN A BOTTOM CONTEXT

- Conforming Bottoms. Bottom peer groups exist in a context of shared vulnerability (“Four Persons in a Bottom Context”). The reflexive response is to coalesce. In coalescing, we feel (and, in fact, may be) less vulnerable. We develop a ‘‘we’’ mentality in which our differences are submerged and we feel connected to one another, supporting and being supported by one another. But then we harden in our we-ness — our closeness to one another and our separateness from all others, from ‘‘them.’’ In our we-ness we become wary of all others, resistant to them, and at times antagonistic to them. In our we-ness, there is pressure from one another as well as self-inflicted pressure to maintain unity. Difference is experienced as threatening to the we, and those expressing difference are pressured to come back into line. Individual action is experienced as threatening to the we and is discouraged. The pressure toward conformity is intense. The cost to individuals is the suppression of their freedom and the opportunity to develop their individuality; the cost to the system is resistance to even the best-intentioned change initiatives and the suppression of energy that could be focused on system business.Each of these scenarios results in stress for individual group members, causes the quality of their relationships to deteriorate, and diminishes the group’s contribution to the overall system. And each of these scenarios is avoidable. Transformation becomes possible with context awareness and choice:

Leadership strategy 3: Recognize the context your peer group is in; adapt to that context without allowing adaptation to harden into dysfunctionality. Develop your peer group into a Robust System, one that strengthens individual members, their relations with one another, and their contribution to the system.

In order to develop powerful peer groups, we need to

A SYSTEM DIFFERENTIATING

A SYSTEM HOMOGENIZING

A SYSTEM INDIVIDUATING

(1) understand the fundamental systemic processes underlying Robust Systems, that is, systems with outstanding capacities to survive and develop in their environments;

(2) recognize how these processes are influenced by context in ways that can limit peer group effectiveness, and

(3) master the processes. Any peer group — Top, Middle, or Bottom — can become a Robust System.

A SYSTEM INTEGRATING

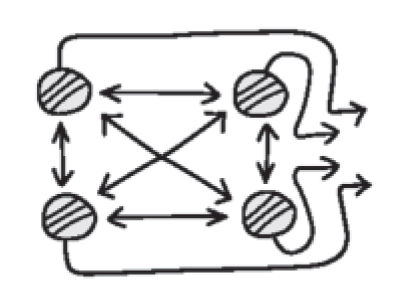

A Robust System differentiates, homogenizes, individuates, and integrates (see “A System Differentiating,” “A System Homogenizing, “A System Individuating” and “A System Integrating”). ‘‘Differentiates’’ refers to the fact that the system develops variety in form and function, thus enabling it to interact complexly with its environment.

‘‘Homogenizes’’ means developing processes for sharing information and capacity across the system. ‘‘Individuates’’ means encouraging individuals and groups to function separately and make independent forays into the environment, experimenting, testing, developing their potential. ‘‘Integrates’’ means enabling a process in which parts — individuals and units — come together, share information, feed and support one another, and modulate one another’s actions in the service of the whole.

Whether we see context or are blind to it, our groups will reflexively adapt. But some reflexive patterns of adaptation actually diminish peer group effectiveness by relying on certain processes while ignoring or suppressing others. When we see and understand context, we can strengthen our groups by bringing the ignored or suppressed processes back into the mix.

- The formula for falling into Top Territoriality is differentiation and individuation without homogenization and integration.For Top groups in the context of complexity and accountability, the reflexive response is to differentiate and individuate, that is, to develop a variety of forms and processes for coping with complexity and for the parts to function independently of one another in the pursuit of these separate strategies and approaches. Thus far, this is all to the good. It is when Top groups fail to balance differentiation and individuation with homogenization and integration that they fall into destructive territoriality. In light of this peril, how can leaders develop a robust Top peer group? The leadership challenge for Top groups is not to differentiate less but to homogenize and integrate more, to share high quality information with one another, to spend time walking in one another’s shoes, to work together on projects other than their specialized arenas, to function as mutual coaches to one another in which all Tops are committed to one another’s success. Such forms of homogenizing and integrating activities serve to strengthen the group’s capacity. The new formula for Top peer power becomes: Homogenization and integration strengthen differentiation and integration.

- The formula for falling into Middle Alienation is individuation without integration. For Middle groups in the tearing context, the reflexive response is to individuate: to separate and function independently as they supervise, manage, lead, coach, or otherwise service the groups they are charged with serving. This is an adaptive response to the tearing context. It is when individuation is not strengthened by integration that the fractionated pattern described previously develops. In light of this peril, how can leaders develop a robust Middle peer group? The leadership challenge for Middle peers is not to individuate less but to integrate more: meet together regularly with just Middle peers, share information gleaned from across the system, use their shared intelligence to diagnose system issues, share best practices, solve problems, work collectively to create changes that individually they are unable to achieve. The new formula for Middle peer power becomes: Integration strengthens individuation.

- The formula for falling into Bottom Conformity is homogenization and integration without individuation and differentiation. For Bottom groups in the context of shared vulnerability, the reflexive response is to coalesce. Coalescence is a process in which unity is maintained by homogenizing (emphasizing commonality while suppressing differences that could divide) and integrating, that is, sharing resources and supporting one another in common cause. Coalescence is an adaptive response to shared vulnerability; it is when homogenization and integration are not balanced by individuation and differentiation that the groups fall into stifling and destructive conformity. So how to develop a robust Bottom peer group? The leadership challenge for Bottom peers is to strengthen themselves by encouraging differentiation (Let’s explore multiple approaches to coping with our vulnerability) and individuation (Go out there and see what unique contribution you can make). Differentiation and individuation are not experienced as threats to unity as long as they are pursued with the goal of strengthening the we rather than weakening it. The formula of, In unity there is strength, is changed to, In diversity there is strength. In the language of group processes, the new formula for Bottom peer power becomes: Individuation and differentiation strengthen homogenization and integration.

Principle 4: Overcoming the Illusions of System Blindness

Principle 4: Our consciousness — particularly how we experience others — is shaped by our relationship to them. Change the relationship, and we experience them quite differently.

One reaction to any of the group strategies described could be: Very interesting, but it won’t work with my people. And why won’t it work with your people? Well, it’s because of their temperament, or needs, or motives, or level of maturity, and so forth. We find ourselves back into experiencing others through a personal rather than systemic lens. When Tops are in the ‘‘mine’’ mentality, Middles in the ‘‘I’’ mentality, and Bottoms in the ‘‘we’’ mentality, the feelings they have toward others feel solid, firmly grounded in the characteristics of these others. Simply a matter of who they are. And any notion that you might feel differently toward them feels far-fetched. Yet these solid, firmly grounded experiences are in fact the illusions of systemic blindness. Change the relationship, and the feelings change.

In the Power Lab experience (described in Part I of this article), we demonstrate this illusion quite dramatically. A central feature of the program is a multiple-day intensive societal experience in which participants are randomly assigned to Top, Middle, and Bottom positions. With great regularity, Tops fall into territorial issues, Middles become alienated from one another, and Bottoms become a powerfully connected we. And all relationships seem firmly grounded in the reality of who the people are. Then there is a second experience in which all roles are shifted; the powerfully bonded Bottoms are now in different contexts: some as Tops, others as Middles, and others as Customers. And in short order, love is transformed into impatience, annoyance, competition, aggression. Previously territorial Tops and alienated Middles are now bonded Bottoms. They all experience the power of context. That can and should be a humbling experience.

There may be many roads leading to systemic understanding. As an educator, my favorite is this: I prefer to come to a system intentionally knowing nothing about it: reading no reports, interviewing no one. And then I give a talk on Top Teams and Middle Peer Relationships and Bottom Group think. The presentation is about context and how context shapes our experiences of ourselves and others, and the dysfunctional scenarios that can follow. The power comes when people identify themselves and their system in this pure abstraction. How does he know this about us? Clearly whatever is happening to us is not simply about us or our particular organization. Something else must be going on. And that questioning creates the opening for systemic understanding and intervention: for Tops to pay more attention to homogenizing and integrating activities, for Middles to regularly integrate with one another, and for Bottoms to strengthen themselves by building individuation and differentiation into their survival strategies. The challenge for all is to see, understand, and master systemic context.

Systems in Practice: The Case of the Rigid Manager

The following case illustrates the people-in-context ideas I’ve described in this chapter, and it also supports what could be regarded as a fifth principle toward developing system insight:

Principle 5: Seeing people opens up deep but potentially limited personal interventions; seeing context opens up comprehensive systemic interventions.

A change intervention that has been successful in division A of Ace Manufacturing is being introduced into division B with the help of a team of consultants. One snag is that B’s division head is less than enthusiastic about the project. Our department managers are having enough trouble keeping up with day-to-day demands without dealing with the complexity of a whole new initiative. Still, the initiative has been introduced, and five of the six department managers seem invested in making it work despite its apparent difficulties. Charles, the sixth manager, has been ignoring the initiative. To him, it is as if it doesn’t exist. Charles is clear about his boss’s priorities, and his boss’s priorities are Charles’s priorities.

The consultants have attempted to work with Charles, with little success. They interpret Charles’s apparent resistance from a personal developmental framework: seeing him as being stuck at a developmental level at which he is unable to separate himself from the demands of authority. If Charles and the initiative are to be successful, Charles needs to be helped to move through that stage of development and acquire greater independence.

Meanwhile, the other department managers, each operating independently of the others, are grappling with both the requirements of the new change initiative and the continuing demands of the division head, who is increasingly unhappy with them. They have been lax on their paperwork, reports not being timely or thorough, and there have been too many complaints from people in their operations. None of this is a problem for Charles. His paperwork is fine, his reports are timely and thorough, and as far as the division head is concerned, Charles’s operation is running smoothly.

Charles may in fact be stuck at this level of development, and it could be useful to help him move through that stage. But a richer understanding of this situation with more powerful intervention possibilities emerges when observed through a systems lens.

A Systemic Picture. Charles, with his apparent inability to separate himself from authority, is but one piece of a total system scenario involving the relations between and among the division head (Top) and the department managers (Middles). A deeper understanding of this situation and a more global intervention strategy emerges when we take into account the contexts in which people are functioning:

- Top Context: Complexity and Accountability. To the division head, this new initiative is being experienced as another complication in an already complex world. This feeling is reinforced by the lax reports from department managers and the complaints coming from their groups. Progress on the change initiative seems incoherent. The division head receives very different reports.

- Middle Context: Tearing. Charles is not the only Middle torn between the requirements of the new initiative and the day-to-day demands of the job. Department managers are coping with the tearing in different ways. Charles reduces the tearing by aligning up; the division head’s priorities are his priorities. The division head has no problem with Charles, but the consultants do because Charles’s priorities are not their priorities. Meanwhile, the other department managers are coping with the tearing differently. Some are aligning with the consultants’ priorities; the consultants are pleased with their efforts, but the division head is not. Others are attempting to please everyone with limited success.

- Middle Peer Group Context: Tearing. Each department manager faces this tearing alone. There is no Middle peer group with a coherent strategy for handling their tearing and implementing (or agreeing not to implement) the change initiative.

A Systemic Intervention. The key leverage point is the Middle peer group. Currently there is no Middle group with an independent perspective on the current situation or a coherent strategy for dealing with it. Middles, being in their independent, separate ‘‘I’’mentalities, do not experience the need or potential for collective power in their group. In fact, their competitiveness with and evaluations of one another, all consequences of the ‘‘I’’ mentality, support their not working collectively.

A first step in a systemic intervention is to develop system knowledge: education regarding context. Rather than approaching the situation head-on, a conceptual presentation or simulation would be aimed at illuminating context, primarily the Middle context and the challenges that context raises for individual Middles and the Middle peer group. The goal is for the abstract to illuminate the concrete current situation: why people are feeling the way they do and how the development of a powerful, independent Middle peer group can fundamentally transform the situation. Then it is up to department managers to work on developing such a group—one that meets regularly, in which members share information about what’s working for them and what’s not. They support one another, coach one another, and, most important, develop an agreed-on strategy for handling the change initiative.

If Middles are successful in that effort, a number of problems are resolved. The complexity of the Top (division head) is reduced; he is receiving more consistent information from his Middles, and the change initiative appears to be managed more uniformly. Individual Middles are less torn, alone, weak, unsupported; all Middles feel part of a powerful and effective peer group; the change initiative is pursued more consistently. And, one would hope, this change initiative, when implemented effectively, will have a positive effect on the lives of all system members. From this persons-in-context framework, the focus is less on ‘‘fixing’’ any one person than on helping all parties see, understand, and master the systemic contexts they are in.

Implications for Leadership Development

Seeing context is an unnatural act. We do not see others’ contexts; all we see directly are their actions or in actions. Nor do we see our own contexts; what we see and feel are specific events, actions, and conditions. So the challenge is how to educate leaders regarding context.

Conceptual Presentations. This article is one example of education in context. Leaders, like everyone else, welcome the opportunity to organize what appear to be random, chaotic phenomena into actionable abstractions — finding the simplicity in complexity. This framework of Top, Middle, Bottom, Customer does that. It resonates with leaders’ day to-day experiences; they can readily see themselves as moving in and out of these contexts; and those with at least minimal self-awareness can recognize the lure of the disempowering reflex responses. Along with awareness, the framework offers clear choice: alternative strategies for empowering self, others, relationships, and systems. In this sense, this is a teachable framework, whether through chapters and articles such as this, presentations, case studies, animations, theatrical dramatizations, or other media.

Executive Coaching. One-on-one coaching can be an important tool of education in context. This, of course, requires that coaches have a deep grasp of context first in their own lives and then in their ability to see it operating in others. The coach can help the leader take into account the context of others. What is their world like? What are they wrestling with? How are they likely to experience this initiative of yours? And what can you do to ease their condition in a way that makes it possible for them to do what you and the system need them to do? A coach can help leaders be aware of their own context and the choices available to them. Are you unnecessarily sucking responsibility for this up to yourself and away from others? What are the consequences of doing or not doing that? Are you sliding in between others’ issues? What are the consequences of your doing or not doing that? The coach’s job is not only to help create awareness and choice in the moment, but also to educate leaders such that context consciousness becomes a regular component of their analytical framework.

Experiential Education. Well-designed organization simulations enable leaders to experience directly the consequences of context blindness and the possibilities that come with seeing, understanding, and mastering context. There is a difference between knowing these concepts intellectually and experiencing them directly in the heat of action. In a stroke of synchronicity, as I was writing this article, I received an email from an Organization Workshop trainer who had just completed a workshop with the executives of his organization. He wrote:‘‘The best part of it was [that] the group has had a lot of prior exposure to [the concepts of] choice and responsibility. So this was for them a fantastic example of how the theory of choice/responsibility isn’t as easy as it sounds.’’ Experiential education can provide this kind of humbling experience that sets the stage for real knowing.

Conclusion

A missing leadership ingredient is the ability to see, understand, and master the systemic contexts in which we and others exist. In our person-centered orientation, we tend to be blind to context, and that blindness is costly.

When we are blind to others’ contexts, we misunderstand them, have little empathy for the challenges they are facing, misinterpret their actions, react inappropriately to them, and fall out of the potential for partnership with them. When we are blind to the contexts we are in, we are vulnerable to falling into patterns that are dysfunctional for ourselves and our systems as burdened Tops, torn Middles, oppressed Bottoms, and screwed Customers. And when we are blind to our groups’ contexts, we are vulnerable to falling into the dysfunctional patterns ofTop territoriality, Middle alienation, and Bottom group think.

With system sight, all of these dysfunctions can be avoided; we are able to interact more sensitively and strategically with others who are Tops, Middles, Bottoms, and Customers; we are able to create more thoughtful, creative, and productive responses when we are Top, Middle, Bottom, and Customer; and we are able to create peer groups whose members value and support one another and who collectively make powerful contributions to their systems. All of this can be taught — just as we know that the earth revolves around the sun even though our direct experience is the other way around. The other day, I heard my young grandson describing how the other kids in class were grousing about something their teacher had done. He said,‘‘Don’t they get it? She’s just a Middle.’’ So maybe early education would be a productive path to develop.

NEXT STEPS

A Framework for Total System Empowerment

Each of us, regardless of our position in the organization, needs to:

- see ourselves as constantly shifting in and out of Top, Bottom, Middle, and Customer conditions,

- know that in each condition we have the system power potential for strengthening the system’s ability to survive and develop, to cope with the dangers in its environment, and to prospect among its opportunities,

- recognize that when we’re in the Top condition, our system power potential is to function as Developers, in the Bottom condition as Fixers, in the Middle condition as Integrators, and in the Customer condition as Validators,

- and, in order to achieve the system power of these conditions, avoid the reflex responses: sucking up responsibility when we’re Top, holding higher-ups responsible when we’re Bottom, losing our connectivity when we’re Middle, and holding delivery systems responsible for delivery when we’re Customers.

These forms of system power enhance one another and together create Total System Power.