The establishment of a goal is generally based on a place or state one wants to be at in the future, as compared to where one is currently in the present. The variance, or gap, between the current state and the desired future state is then used to create motivation for the activity required to transform the current state into the future state.

TEAM TIP

When you set a goal, consider whether you’re focusing on “closing the gap,” “progress,” or “raising the bar.” The latter will more consistently produce ongoing success.

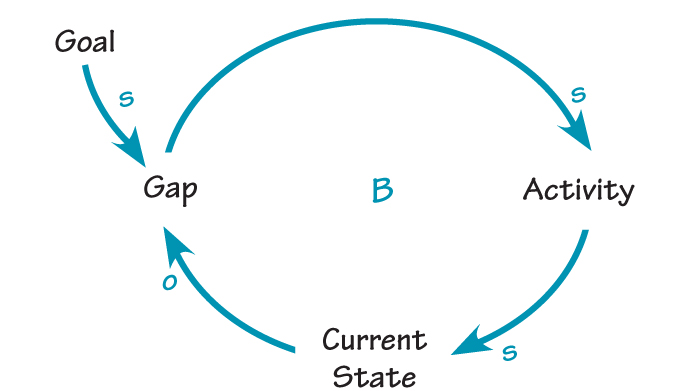

Nevertheless, this tendency to stop short generally accompanies goal setting. When you establish a goal, you essentially create a balancing structure (see “Goal Setting Loop”). In this structure, the difference between the goal and the current state creates a gap that promotes activity. The activity tends to move the current state toward the goal. As the current state moves closer and closer to the goal, the gap gets smaller and smaller. And as the gap gets smaller and smaller, less of an inducement exists for further activity to move the current state toward the goal. Over time, the rate of progress declines. It’s like trying to walk to a doorway, and each step you take is half the remaining distance to the door. Each step brings you a bit closer, yet you never really reach the door.

Goal Setting Loop

Raising the Bar

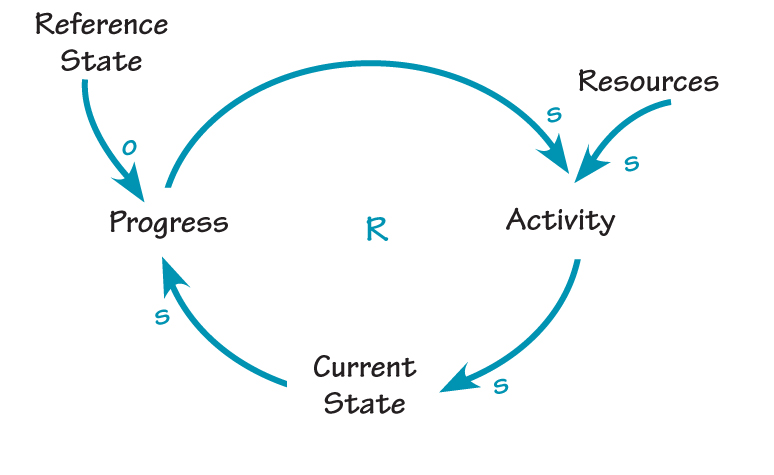

Suppose we change the structure so that rather than base activity on the gap between the goal and the current state, we base activity on progress, that is, how far we’ve advanced from the initial state. Using our 100-yard dash analogy, a runner following this strategy would push even harder as she headed through the finish line rather than slowing down and stopping. The structure should then look more like the diagram “Progress Loop.”

In this scenario, as activity increases, the current state moves closer to the goal. As the current state moves closer to the goal, progress increases. And finally, as progress increases, activity increases. We gone full circle and have produced a reinforcing loop rather than a self-limiting balancing structure.

However, all this activity isn’t for free. Activity is the result of applying available resources to produce movement. By including limited resources (see the “Resources” variable in “Progress Loop”), we create a more realistic situation. Activity is relatively limited for some period due to limited progress. Once progress begins to be produced and sensed, activity begins an exponential climb, at least until it runs into a resource limit. At this point, activity becomes flat, and progress continues at a rather linear rate. This will continue until progress runs into some other limiting factor. There are always limits to growth along the way somewhere, and sometimes they are not always tangible.

Goal Setting Loop

The best way to overcome this situation is to alter the structure so that rather than consider progress based on a single reference point that doesn’t change, you periodically reset the reference point—a continual raising of the bar. Even so, progress is likely to become more difficult in time. The actors in the system will have to evolve their approach to creating progress from incrementally changing, to redesigning, to rethinking their methods. Vision should be used to continually assess movement of the current state to ensure progress is in an appropriate direction.

Gene Bellinger is the cofounder of OutSights, Inc. He has guided numerous clients through successful conceptual development and adoption of their knowledge architecture. Additionally, Gene is the author of numerous articles on knowledge management, organizational development, and systems thinking. Please refer to his website at www.systems-thinking.org/.