Imagine that you’re sitting in the company cafeteria with some colleagues, munching sandwiches and discussing the latest resignation from the customer service group. “I don’t get it,” you say. “Why do people keep leaving?” Marina, one of the few people left in customer service, adds, “This is getting bad—I don’t see how the rest of us can deal.” “Hmmph,” grumbles Thomas, from order processing. “It’s worse than that—nobody can ask you folks for anything these days without getting their heads bitten off!” You glance back at Marina’s tense face and find yourself wondering whether she’ll be the next one to go.

After lunch, you all decide to sketch out a causal loop diagram of the situation. You’ve heard that as one of the basic tools of systems thinking, CLDs can open up new insights into a problem; you’ve also heard that they work best when you state the variable names in certain ways.

Getting Started

But what makes good variable names, and how do you identify them from a gripe session like the one described above? Here are a few guidelines to get you started (also see “Will the Real Variable Name Please Stand Up,” V9N1):

- Use nouns instead of verbs, action terms, or words suggesting a direction of change.

Example: Number of Products Sold NOT Sell Revenue NOT Increasing Profits By using nouns, you let the CLD arrows show the action.

- Use a neutral or positive term whenever possible.

Example: Morale NOT Bad Feelings Job Satisfaction NOT Job Dissatisfaction Such terms help you avoid confusing double-negatives that can happen when reading a CLD. (For example, “job satisfaction declines” is much easier to grasp conceptually than “job dissatisfaction declines.”)

- Identify hard-to-measure variables, such as “Experience Level” or “Trust,” as well as more concrete variables like “Orders” or “New Hires.” Those intangible variables are often just as important—if not more so—than the quantifiable ones.

Once you’ve properly named the key variables in your problem situation, you can start to identify the causal relationships between them and link them in one or more balancing or reinforcing loops.

So, let’s return to your gripe session with Thomas and Marina. As the three of you prepare to identify key variables from the problem situation, you agree to act as the moderator for this part of the process. Your job is to ask questions that will help Thomas and Marina find potential variable names in your earlier conversation. But don’t stop with just the spoken words—sometimes you can detect perfectly good variable names in unspoken signals like facial expressions or tone of voice.

To begin, let’s work our way through the conversation. All the while, we’ll examine the various comments—and any important nonverbal happenings—for promising variable names. Look again at the first statement that was made: “I don’t get it. Why do people keep leaving?” Your question to Thomas and Marina might be: “What specific, neutral noun phrase could convey the meaning in this statement?” Possible answers could include “Customer Service Turnover” or “Number of Customer Service Resignations.” Congratulations—you’ve nailed down your first variable name!

Now let’s look at the second statement from the conversation, made by Marina: “This is getting bad—I don’t see how the rest of us can deal.” If you were to ask Marina, “What do you mean?” she might respond with, “Well, every time someone in customer service leaves, there are fewer of us left to process the incoming phone orders—our workload just gets worse.” Voilá! You can now formulate another variable name: “Workload.”

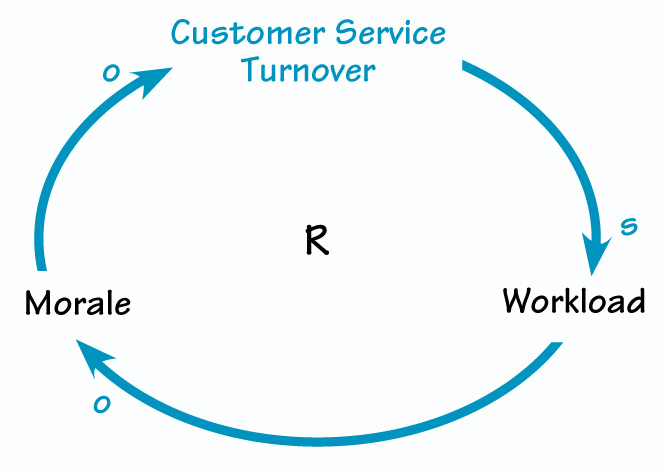

TURNOVER IN CUSTOMER SERVICE

As customer service representatives resign, the workload increases for the remaining staff. Morale falls, as the reps scramble to keep up with the incoming calls. Eventually, even more people resign, leading to yet bigger workloads and worse morale.

Let’s next take Thomas’s statement: “It’s worse than that—nobody can ask you folks for anything these days without getting their heads bitten off!” “What’s happening here?” you ask Thomas. He replies, “They’re so irritable!” You nudge him to think of a noun, and he comes up with another variable name: “Morale.” As you reflect on the tension that you sensed in Marina, and on Thomas’s observations about short tempers, these nonverbal clues confirm that morale is indeed a key variable.

From Variables to CLDs

Once you’ve properly named the key variables in your problem situation, you can start to identify the causal relationships between them and link them in one or more balancing or reinforcing loops (see “Causal Loop Construction: The Basics,” V7N3). When you have completed the diagram, walk through the loops and “tell the story” to be sure they accurately capture the behavior being described (see “Turnover in Customer Service” on p. 9).

In real life, identifying variable names involves many more iterations than we’ve shown in this case. However, it’s this very act of refining the names that lets you construct a powerful CLD—one that will yield rich insights into the problem and maybe even point the way to a solution. In this case, Marina might share the loop with others in her department. The group could brainstorm possible interventions, such as accelerating the hiring of replacement workers or temporarily reducing the workload by postponing nonessential tasks. Of course, they will want to map out the potential unintended consequences of each of these proposals as well, to make sure the solution doesn’t make the problem worse!

Lauren Keller Johnson is a freelance writer living in Lincoln, Massachusetts.