Karen was often irritated by Jenny when they worked together. It seemed to Karen that, whenever tensions rose between the two of them, she and Jenny expressed their feelings differently. Jenny stopped communicating and tried to sort things out on her own. On the other hand, Karen sought to share her thoughts and emotions. She preferred to work through their challenges together, even if the process sometimes got heated. Most troubling to Karen was that, whenever she started to convey how she felt, Jenny rolled her eyes, sighed, and gave every indication she thought she was superior.

Karen suspected that these conflicting styles had a lot to do with personality differences. She had once taken a survey that showed she was a “Feeler,” and she was pretty sure that Jenny was a “Thinker.” Knowing this, though, didn’t change the frustration she felt when problems arose.

Because the challenges with Jenny seemed so minor, Karen thought they should be easy to fix. It was obvious that Jenny shared Karen’s passion for their work. Plus, Jenny had brilliant ideas that often led to breakthroughs on tough issues. Karen only wished that Jenny weren’t so cold and distant.

Although they may seem trivial, the personal differences that Karen experienced in her relationship with Jenny had a significant impact on their working relationship. Fortunately, while these opposing styles may generate conflict, they also offer great richness in tackling complex issues. But in order to get out of counterproductive patterns of interaction that have created problems in the past, Karen needs a new way of viewing differences: one that enables her to live with the tensions differences generate, create a rich vision of what she wants to create, and be flexible in the pursuit of her vision. Otherwise, Karen’s current way of thinking will continue to limit her ability to respond constructively to Jenny and others.

No doubt you, too, are aware of differences between you and others in your organization. How can you deal with these differences in productive ways? And how can you use them to build your own self-knowledge and interpersonal skills? One promising approach stems from a school of thought known as “Dilemma Theory.”

A dilemma is a choice between two options, both of which are attractive but appear to be mutually exclusive: an “either/or” scenario.

Dilemma Theory

Differences have always been a basis for learning. When people travel, they find themselves stimulated by the cultural differences they encounter, often returning home with new understanding and appreciation of themselves and their communities. But differences can also serve as the basis for intractable conflict and struggle. When we encounter someone whose worldview is diametrically opposed to our own, we often fall into an “us” versus “them” and “good” versus “bad” dynamic.

Dilemma Theory, based on the work of researchers Charles Hampden-Turner and Fons Trompenaars, seeks to help us overcome these barriers and learn from differences. Hampden-Turner summarizes the philosophy as follows: “We can never grow to become great business leaders until we actively strive to embrace the behaviors and attitudes that feel most uncomfortable to us. The most effective management practices are those that gently force engineers, managers, and employees to embrace the unthinkable.” Hampden-Turner and Trompenaars focus primarily on cultural differences, but the concepts they developed can help to explain the dynamics associated with any kind of differences.

As they point out, a dilemma is a choice between two options, both of which are attractive but appear to be mutually exclusive: an “either/or” scenario. You face dilemmas every day: whether to work on a project alone or with others; whether to give attention to details or focus on the “big picture”; whether to confront someone’s inappropriate behavior or pass over it; whether to stay with what you know or try something new.

While such dilemmas may seem straightforward, they are rich with dynamic complexity. The dynamism stems not from the simple choice that a dilemma presents, but from the mechanisms that people and societies develop for making such decisions. How we become skilled at handling dilemmas has an enormous impact on the outcome. In this context, being skilled means competently performing a task without needing to consciously focus on it. When we repeatedly do something, we eventually reach the point when we no longer need to call to mind the steps it requires; we just do them. I have become skilled in the use of computer keyboards, so as I type, I do not have to deliberately hunt for the right keys to make words. I think of the word I want and my fingers make it happen without any apparent thought on my part.

Just as we become skilled at physical tasks such as typing, we gain mastery in handling dilemmas. If we repeatedly resolve dilemmas by choosing one option over the other, the option we choose becomes an unconscious preference. Over time, we stop being aware that we are making a choice — we simply assume it is the best course of action. These deeply internalized preferences become values that shape the decisions we make and the actions we take.

Many people believe that their way of dealing with something is obviously superior, even when they encounter others who routinely make the opposite choice. In this situation, it is easy to characterize different choices as absurd or based on ignorance. For Karen, the rightness of working collegially and expressing her emotions was something she felt from deep within and found hard to put into words. Little wonder she found it perplexing when Jenny worked in a contradictory way.

Personality differences also play an important role in the formation of values. We are each born with innate characteristics that shape our preferences and interests (Sandra Seagal and David Horne’s work on Human Dynamics is one framework for understanding variations). So both nature and nurture give rise to the differences we encounter.

Universal Dilemmas

Just as people develop a set of values based on the cumulative effect of the choices they make, so do communities. All communities encounter dilemmas, and some dilemmas are universal. Universal dilemmas include:

- Whether (a) rules should apply to everyone or (b) exceptions should be made depending on who is involved.

- Whether status should be awarded (a) on the basis of one’s position in the community or (b) on the basis of what one has achieved.

- Whether (a) the needs of the community should outweigh the rights of individual members or (b) vice versa.

While these dilemmas are universal, the ways in which communities resolve them are not. Each society will develop its own pattern of values, perhaps putting (a) ahead of (b) with one dilemma but (b) ahead of (a) with another.

What determines which values develop in a particular community? It depends on the conditions that exist when the community first encounters a dilemma. All manner of variables have an effect. The personality dynamics of influential community leaders — the “core group,” to use the term coined by Art Kleiner — play a key role. The history of the community and its present needs all shape how it resolves a dilemma. When a community repeatedly resolves an issue by giving priority to one option, what was once a conscious choice becomes an unconsciously held value.

We generally don’t examine taken-for-granted ways of doing things until we encounter someone who does things differently.

Values are self-perpetuating. For example, if we value achievement — rewarding people for what they accomplish rather than who they are — we are naturally interested in how we can measure it. Having established a way of measuring achievement, we start to do so. In this way, we create an infrastructure to support a value that started off as a preference for one way of acting over another. As we use the infrastructure, we reinforce the value and strengthen our preference for it.

On an individual level, when children grow up, they take for granted that the way their family operates is the norm — how they celebrate holidays, deal with money, resolve conflicts, and so on. In the same way, people do not usually question the values of the community in which they live. We generally don’t examine taken-for-granted ways of doing things until we encounter someone who does things differently, whether at an individual or group level.

Dynamics of Difference

What happens when people with opposite values — such as Jenny and Karen — interact? The outcome is typically not what we would hope. Because a dilemma involves options, both of which are advantageous, the values represented in the dilemma are also complementary. The more one of the values is expressed, the greater the need for the other becomes. Jenny and Karen have the potential to balance one another, making up for each other’s shortcomings and supporting each other’s strengths, and we might hope that they would find ways to capitalize on their complementary skills. But two phenomena often prevent that from happening: skilled incompetence and schismogenesis.

Skilled Incompetence. The reason a dilemma is challenging is that both options are attractive: Each provides real — though different — advantages. In our story, Karen benefits from being expressive, and Jenny benefits from keeping her emotions in check. But when one option becomes an unconscious preference, it is at the expense of the other. So the more that Karen pursues the value she derives from acting expressively, the more she misses out on the advantages of objectivity.

While Karen values subjectivity, she isn’t blind. She can see that Jenny benefits from her objectivity. She may think, “I wish I was more like Jenny,” and decide to change in that direction. But despite her determination, Karen may still operate off an unconscious preference for subjectivity. For this reason, she may say one thing while at the same time do the opposite and not be aware of the discrepancy. Chris Argyris coined the term “skilled incompetence” to describe the mismatch between what people say and what they do.

This pattern of behavior can also happen at an organizational level. Companies may publish lists of values, but these often express qualities that people think are needed rather than ones that the organization actually possesses. In all probability, a quality will make it onto the list of “corporate values” because it is something the organization does not value!

Schismogenesis. Another dynamic that occurs when opposites interact is what anthropologist Gregory Bateson termed “schismogenesis”: the splitting apart of complementary values. Schismogenesis happens when an initially small difference gets progressively bigger. Imagine that Karen has come up with a breakthrough on a project that she wants to share with Jenny. She goes to Jenny’s office and excitedly blurts out that she has news. Jenny is overwhelmed by Karen’s energy, thinks Karen should calm down, and tries to encourage her to do so by lowering her own voice and speaking slowly. Karen thinks Jenny doesn’t understand the importance of the message, so she ramps up her level of enthusiasm. Jenny gets quieter and calmer. Karen gets louder and more excited. What started off as a small difference has become enormous through the course of the interaction.

FROM PREFERENCE TO VALUE

Something else has happened, too. Karen and Jenny have become polarized, with a distorted view of what their values represent. How so? When seen through the lens of Dilemma Theory, a value is a preference for acting one way rather than another. This difference also depends on who else is involved. Karen values expressiveness because this term describes the difference she sees between herself and others she interacts with. But in many communities throughout the world, Karen would be viewed as the least expressive person.

Nevertheless, Karen has come to consider expressiveness as something that defines who she is. She doesn’t think, “I have a stronger preference for expressing and acting on my feelings than Jenny.” Rather, she says to herself, “I am a Feeler.” Thinking of herself in this way makes a tremendous difference to the repertoire of actions that Karen allows herself to use. Viewing her own and Jenny’s values as permanent characteristics, Karen feels compelled to act in harmony with her values. She shuns the alternative way of acting.

How will this pattern of behavior affect Karen when it comes to learning and personal mastery? Our values influence what we are ready to learn. Karen is attracted to forms of learning that support her preference for emotional expressiveness. She may reject opportunities to learn what she does not value, such as the use of rigorous analytical decision-making tools. She is not naturally interested, and it just feels wrong somehow.

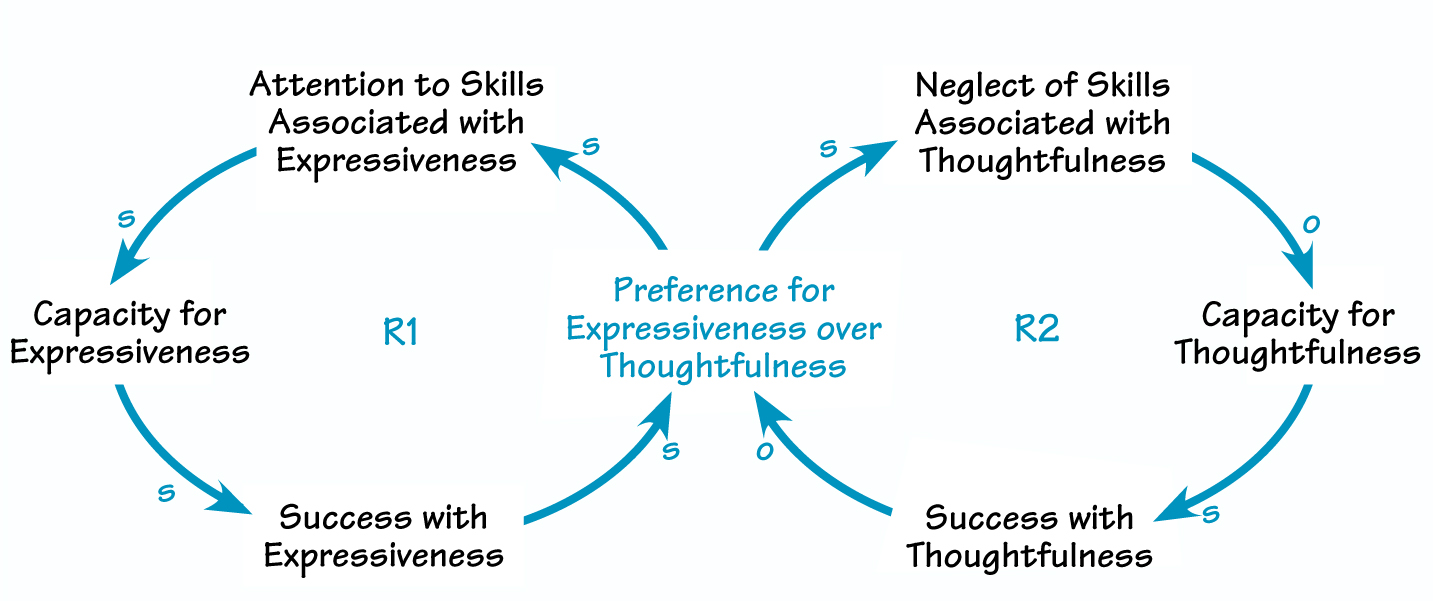

By bounding the scope of her inquiry, Karen limits her capacity to create what is really important to her. Her values push her to learn some things and neglect others. While she may be aware of her need to gain competency in those other areas, what she sees as personal characteristics play a crucial role in shaping how much effort she invests in her learning efforts. This process represents a “Success to the Successful” archetypal structure, in which Karen reinforces the values she already has and neglects areas in which she could benefit from growth (see “From Preference to Value”).

Reconciliation

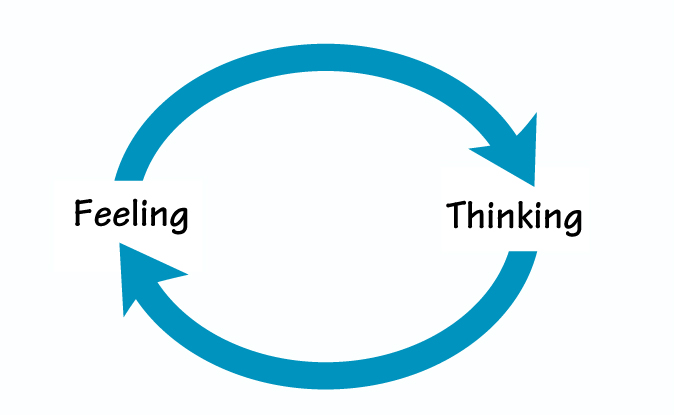

To reap the benefits from diversity, Dilemma Theory encourages people to look for ways of reconciling the conflicting values they encounter. While the dynamics of culture and personality often lead people to value one option and neglect the other, a dilemma is a dilemma because both of the options are important and needed. Reconciliation involves understanding the circularity of the relationship between values. The two options involved in a dilemma — the potential values — are complementary. The more we do one, the more we need to do the other. We could diagram the relationship as shown in “Complementary Values”.

Schismogenesis is a process that disrupts the connection between the two values. Reconciliation does the opposite; it strengthens the connection. Rather than encouraging one or other of the values to be expressed, it encourages the flow of movement between the values so either or both can be expressed, depending on what the situation demands.

COMPLEMENTARY VALUES

The two options involved in a dilemma the potential values—are complementary. The more we do one, the more we need to do the other. Reconciliation involves understanding the circularity of the relationship between values.

Imagine what would happen to the relationship between Karen and Jenny if they reframed their values in ways that still indicated their individual preferences, but showed an appreciation for both parts of the dilemma. Karen might move from thinking “I’m a Feeler” to “Before making a decision, I like to test ideas by experiencing how they affect my emotions.” By reframing her image of herself in this way, Karen recognizes that if she exercises her capacity for feeling, she can improve the quality of her own and others’ thinking. And improving the quality of thinking has a positive impact on the emotional environment in which she works.

Jenny might move from the stance “I’m a Thinker” to “I prefer to articulate thoughts in ways that enable people to examine and express their feelings and opinions.” Jenny recognizes that her capacity for thinking enables her to invite others to express their feelings in productive ways. Doing so stimulates and challenges her to increase the quality of her thinking.

In this way, while Karen and Jenny retain their own preferences, they can design a way of working together that they both find satisfying. Imagine we were to watch them at work. While they were getting used to this new way of framing their values, we might see rather deliberate shifts between thinking and feeling. They might verbalize the need to move from one mode of operation to another:, “Perhaps we should generate some new thoughts based on what we’ve heard” or “Let’s take some time to check out our feelings about what’s been said.”

Over time, Jenny and Karen would likely become more skilled at managing the movement between thoughts and emotions. We would observe a fluidity in their work together, with each bringing feelings and thoughts into play as required. When they have truly reconciled the dilemma, we would be hard pressed to classify aspects of their work as expressions of one or other of the original values.

Many of the challenges we face are socially complex: The people affected are diverse and the array of values is wide. Each situation might involve several pairs of opposing values. As we learn to honor all the values pertinent to a dilemma, we increase our capacity for acting in ways that are sustainable within the system. But what behaviors help us to reconcile values?

Changing Patterns

A number of techniques can give you insight into the dynamics of the differences you encounter. These can prompt you to look at conflict in new ways.

Be Aware. A key to achieving reconciliation is awareness of one’s own thinking and behavior. Schismogenesis can seem normal in an environment in which people are rewarded for living at the extreme of one value. A community may reward those members who are “ideologically pure,” focused on one value to the exclusion of all others. But personal, organizational, and social health require the reconciliation of a range of values. If you concentrate your effort around just one value, you are likely going to mobilize people with other values to become more extreme in their opposition to you. Schismogenesis is fueled by unconscious actions; becoming aware of your actions is the basis for reconciliation.

Look for the Whole. People become polarized when they can see only the good in what they value and only the evil in the values of those who oppose them. As we have discussed, values arise because of dilemmas, and in a dilemma, both options offer something attractive. It follows that there will also be a downside to any value. If a person pursues a value in a single-minded way, then he or she is neglecting a complementary value, and undesirable consequences will likely follow. Practice seeing the whole picture by noticing the gains to be made by pursuing each value represented in a dilemma. Then list the disadvantages of each: what will be lost if you pursue each of the values to an extreme.

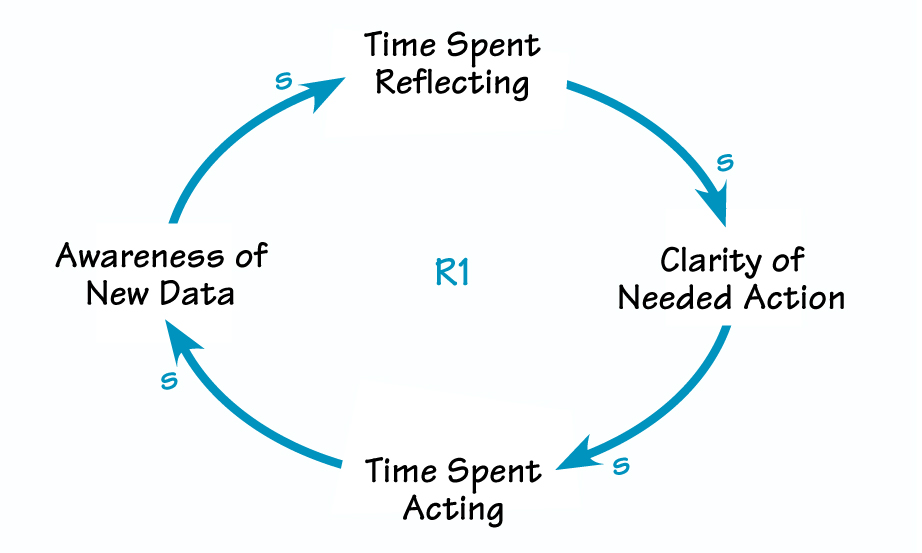

SEQUENCE OF ACTIONS

This causal loop diagram shows how you might move through a sequence of actions that give priority to one value and then another, and so on. In this case, reflection improves our actions, and actions provide new data for reflection.

Bring Values to the Surface.Values often lie hidden beneath the surface, making reconciliation difficult. In a meeting, participants may arrive ready to advocate for the action they believe needs to be taken, based on their underlying values. They will likely push for a variety of actions, and some will be diametrically opposed to others. By asking questions such as “What will we gain from that action?” and “What is it you are interested in?” the group begins to see the values behind the different activities. In addition, teams often make progress by (a) noticing the various actions being advocated, (b) noticing the interests behind each of the actions, (c) consciously scrapping the actions first suggested, and (d) asking “What new action could we design that would address the values that are important to us all?”

Practice Sequencing. Reconciliation involves seeing the relationships between complementary values. We want to create a fluid movement between different ways of acting. To see how this movement might take place, create causal loop diagrams that express how you might move through a sequence of actions that give priority to one value and then another, then back to the original and so on (see “Sequence of Actions”). Practice your sequencing skills on the common dilemmas shown in “Common Dilemmas.”

The Journey of Dilemmas

COMMON DILEMMAS

- Reflection versus Action

- Planned Processes versus Emergent Processes

- Rules versus Relationships

- Individual Rights versus Community Obligations

- Learning versus Performing

- Flexibility versus Consistency

- Collaboration versus Competition

- Equality versus Hierarchy

- Change versus Stability

- Pragmatic Choices versus Ideals

Imagine we could go forward in time to revisit Karen and Jenny, who have worked hard to reconcile the collision between different personal styles that was such a challenge to their working relationship. What will we find? Having dealt with this challenge, will they have freed themselves from all dilemmas? Will conflict be a thing of the past?

Hardly. A dilemma can arise around any difference. Karen and Jenny are unique individuals; they differ from one another in myriad ways. Expressiveness and objectivity were the most prominent differences at the time we became interested in their story. When they resolve that dilemma, new ones will surface. Their work is dynamic, too. It keeps changing, throwing up new situations that bring new dilemmas to the surface. We could say that Karen and Jenny — both individually and in their relationship — are on a journey in which they regularly encounter opportunities to learn from dilemmas.

Does this mean that Dilemma Theory offers nothing but a legacy of ongoing conflict and frustration? No. It doesn’t produce a constant stream of challenges and problems; life does that. And for Karen and Jenny, the outcome is not bleak. Insight into the dynamics of dilemmas has enabled them to view their differences as opportunities to learn, both collectively and individually.

As a result, they no longer have to treat their differences as something to be feared. They have learned that, with careful attention, they can reconcile their dilemmas. They have developed a practice of “thoughtful sensitivity” (or “sensitive thoughtfulness”) that can help them face new challenges. And they appreciate each other’s contribution, knowing that they complement one another in important ways.

When you encounter differences, be resolved to seek ways in which you and others can reconcile apparently conflicting values.

At an individual level, both Jenny and Karen are now able to suspend their values, observing how these influence their reactions and attitudes. Each has gained a deep insight into who she is, an insight she can take with her into her relationships with other people. Each has a greater repertoire for thinking and acting, no longer limited by an unconscious preference. Both are thankful they have learned from the mutual relevance of difference.

When you encounter differences, be resolved to seek ways in which you and others can reconcile apparently conflicting values. Building your capacity in this vital area is the basis for both successful collaboration with others and ongoing development while on your own learning journey.

Phil Ramsey teaches organizational learning at Massey University in New Zealand. He is a regular presenter at Systems Thinking in Action® Conferences and is the author of the Billibonk series of systems stories, published by Pegasus Communications.

NEXT STEPS

- Think of a person — at work, home, in your volunteer work, or elsewhere — with whom you frequently clash. Try to identify the opposing values that you both hold. What steps might you take to reconcile these values? How might viewing these values as complementary affect the ways in which you interact with that individual?

- The article talks about how we come to see personal preferences as things that define who we are. What characteristics have you come to think of as personality traits? What do you gain by pursuing each value? What do you lose? Does shifting from thinking of them as “who you are” to “what you do” change how you interact with others who are different from you?

- Following the model shown in “Sequence of Actions,” draw several causal loop diagrams that show how more of one value eventually leads to the need for the complementary value, and so on. Doing so can help you identify a course of action when you feel caught in an intractable dilemma or chronic conflict.

—Janice Molloy