Leaders like to think that good planning and solid management are the keys to successful change. Yet too often their best efforts, combining their most inspired analysis and shrewdest planning, fall flat or meet unexpected and crippling resistance. What makes the difference? Is it luck? Is it the quality of the people involved in the change project? Is it their delivery?

Seeking answers to this conundrum, we have studied successful interventions by asking participants what made the difference. On one level, their answers reveal little. They say they just did it, or they tried hard. They cite relatively minor suggestions and offhand comments that they took for wisdom. The people we interviewed describe being influenced by experiences outside the work situation: the influence of a book they had read, a lesson learned at home, something a friend said. While leaders and consultants had been working steadily and systematically to help facilitate change, credit is given to what seems like peripheral, almost random events.

The logic beneath these explanations seems unavoidable: People and organizations change — rapidly, strongly, thoroughly — when ready to change. When ready, they will pick up almost anything from the environment and make use of it. Even the slightest nudge from a manager can act as a powerful catalyst. Conversely, when people are not ready to change, they will ignore or resist the best efforts of others to change them. As anyone who has repeatedly tried to act less defensively or more assertively knows, we resist even our own plans to change.

It appears there are deep, underground currents of readiness that, once tapped, serve as powerful catalysts for change (see “A New Theory of Readiness and Change” on p. 3). While this statement may appear mysterious, in fact it reflects two of the most basic premises of science and systems theory. First, physicists have shown that systems outside their normal constraints, systems far from equilibrium, are vulnerable to change triggered by random experience, just as an avalanche can be set off by a loud noise. Second, during periods of disequilibrium, there are many potential paths of growth and development — what biologists call bundles of opportunity. Like new sprouts in spring, these bundles are quietly waiting to be watered and fertilized. By supporting these preexisting bundles, we can fuel and guide change.

People and organizations change — rapidly, strongly, thoroughly — when ready to change.

Readiness takes many forms. Sometimes, people and organizations are in so much pain that they believe they must change. At other times, systems are so out of kilter, so uncertain or disorganized, that they can’t help but change in their efforts to regain their balance. At still other times, people are so open, curious, and receptive to the influence of a new leader that they see every new idea or program as pointing the path to successful action. There is much variety but the core principle seems clear: Organizations change when they are ready.

Readiness is derived from the Greek word, arariskein, which means “fitting” or “joining” or “being arranged for use.” So it is that certain kinds of interventions fit best in particular organizational climates at particular times — and not in others. A system can be entered at any point, because all of its elements are interconnected. This is the nub of it — when interactions are aligned according to both timing and fit, there is readiness.

Three States of Readiness

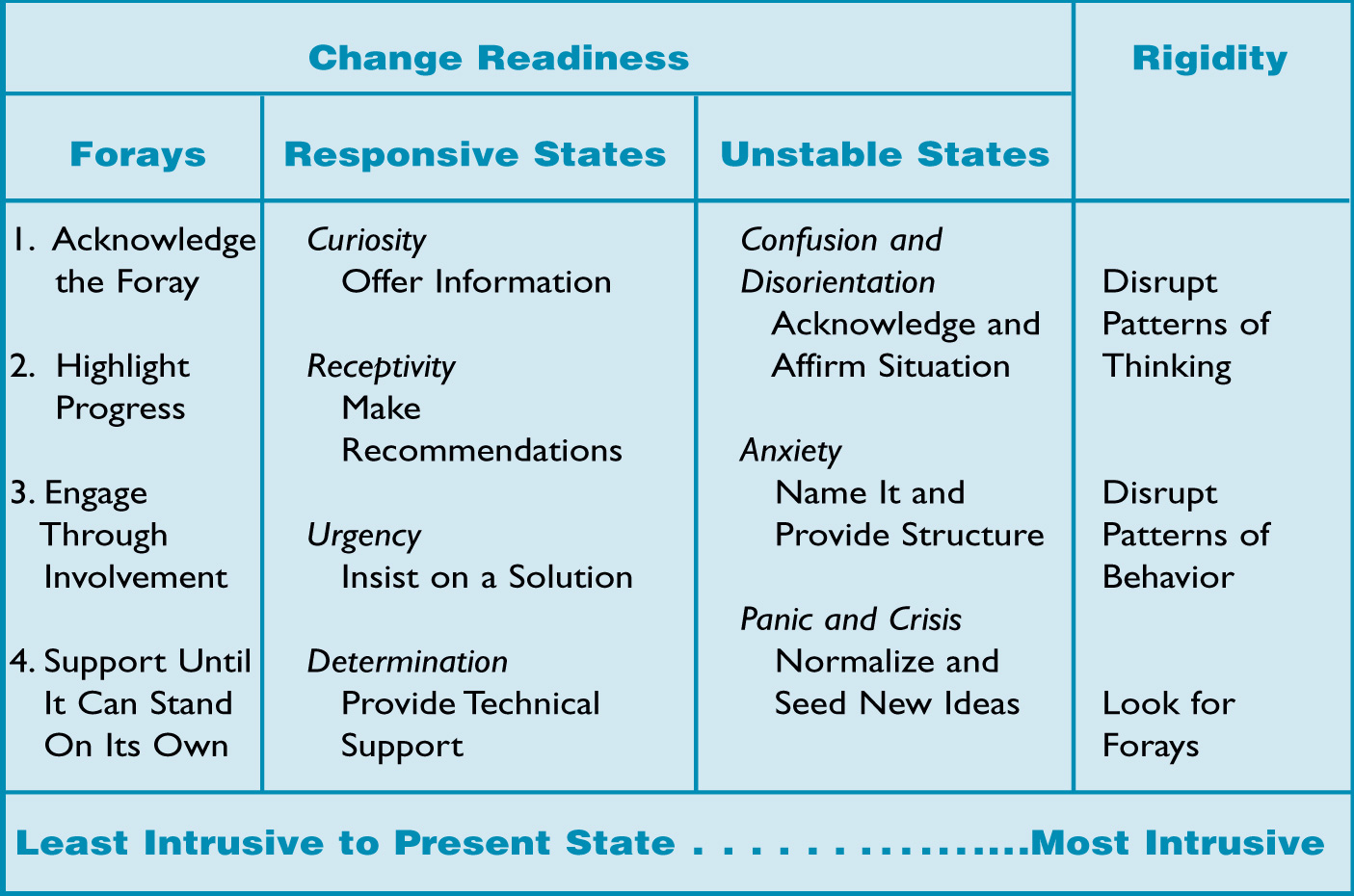

Our research identifies readiness as existing in three different states. Each requires its own specific kinds of interventions. The first of the three states we call forays, which are changes that either have not come to fruition or do not yet exert a strong influence on the whole organization. They are best served in the style of martial arts, by pushing them from behind. In effect, we support and augment forces for alignment that are already in motion. The second type we name responsive states of readiness, such as curiosity, receptiveness, urgency, and determination. They are best served by leaders who provide information, advice, and guidance — a mentoring kind of support. The third type we call unstable states of readiness, like confusion, anxiety, and crisis. They need to be reframed so that people view them as integral aspects of change and cultivated as seedbeds of creative thought.

The idea is to have options, to identify whether and how groups are ready for change, and then to design interventions with those states of readiness in mind. If the intervention targeted to one form of readiness shows signs of failure, we can look elsewhere to intervene. This approach transforms the development of change strategies from guesswork into an empirical process.

A NEW THEORY OF READINESS AND CHANGE

Developmental psychologists, such as Lev Semonovich Vigotsky, look for periods of transition from one stage of development to the next; these transitional periods, in individuals, groups, and organizations, not only signal change, but provide “windows of opportunity” for outside input. The educational theorist, Eleanor Duckworth, has emphasized identifying and capitalizing on “teachable moments.” Evolutionary and systems theorists, such as Gregory Bateson and Irvin Laszlo, assert that “systems in disequilibrium are vulnerable to change,” often random and unpredictable, but, with forethought, open to planned interventions. Leading organizational change theorists, such as Marvin Weisbord, Ronald Heifetz, and of course Kurt Lewin, recognize the importance of readiness. Each, in a different way, has advocated the location of change efforts outside the stable center of organizations and the encouragement of creative processes that thrive when people and ideas interact freely and in unfamiliar ways, before solid plans and strategies are formulated.

Building on these insights as well as on our own reflection and research, we have conceived readiness as a pragmatic enabler of organizational alignment. The intent of our theory is to provide leaders with a broad range of ways to introduce change and alignment. Further, we propose an array of strategies that match well with different states of readiness.

Forays

No matter how rigidly or bureaucratically organized systems are or may appear, there are always changes afoot — people are constantly trying to improve things. Leaders and other change agents must learn to see these forays for what they are: tentative, incomplete moves that people and organizations make to improve their organization. Their efforts are forays from one way of doing or thinking about things into another.

CAPTURING FORAYS

- Acknowledge the foray.

- Highlight the foray’s progress.

- Engage the foray by becoming involved.

- Support the foray until it can stand on its own.

Individually, forays look like this: You resolve to work with your staff in a collaborative fashion and succeed for a few days but then fall back into a more autocratic approach. Organizationally, forays look like this: Within a school in which many teachers and departments plod through their days in a bored, lethargic manner, several instructors come together informally, excited by their challenge, and push each other to innovative work with children. Creative strategies and new work processes that build strength but then get ignored or voted down are forays. Successful projects and teams whose learnings do not spread to the general culture of the corporation — these, too, are forays.

Forays are present in all organizations, all of the time. It is essential for leaders to learn to spot them. If we can identify and support forays to help them grow and use the momentum of people’s own energies, then we have access to the most powerful change agent possible (see “Capturing Forays”). Nevertheless, we may not always succeed in identifying and supporting forays, or our support during stable times may prove inadequate. We may have to wait for unstable times, when patterns of thought and behavior loosen, to push forays into lasting change.

Responsive States of Readiness

Responsive states include curiosity, receptiveness, urgency, and determination. As they approach the task of implementing a change effort, leaders frequently assume responsive states are in play, particularly because they are the easiest stage of readiness to manage. While these states are familiar enough, it’s useful to review the variations to discover when to provide information, planning, advice, or guidance.

Curiosity. Early on in planning and change efforts, staff, board members, volunteer workers, and others are often curious. They are willing to look at and keep an open mind about what leaders have in store for them.

Preferred Intervention Style. Leaders should offer information and suggest alternatives, but avoid pushing. Moving too fast can alienate potentially open-minded people. Scenario planning can be ideal for this state of readiness.

Receptivity. When receptive, people are actively open-minded. They are exploring and not locked into a solution. They have identified a problem but don’t yet have a solution, and they are asking to be told what can be done. New leaders who follow on the heels of organizational difficulties are often met with this kind of receptivity; the early days of their tenure are marked by a honeymoon period.

Preferred Intervention Style. When the organization is receptive, leaders have room to present their own approach to organizational success, or, better still, two or three approaches for the staff to choose from.

Urgency. With urgency, people feel a strong need to do something and, often enough, a strong need for help. Time is of the essence. “Are we too late?”, “Can we fix what is clearly broken?”, “Will our organization survive?”, “Will we let down our clients?”, “Will our jobs be preserved?” Urgency can occur during a sudden downturn in organizational life — funding is declining or unclear; clients are diminishing; the community does not feel well served and says so; a clear opportunity is missed and a competitor takes it.

Preferred Intervention Style. During states of urgency, leaders can and should make clear, decisive suggestions. They can emphasize the type of structure, processes, and working methods that will lead to success.

Determination. When determined, people have identified a problem and believe they must solve it. A private school has been losing enrollment to another local school and knows that it must fund the construction of a new building in order to compete; a state agency says it will only fund larger community-based organizations, leading a smaller organization to acquire or merge with a partner; a board feels its executive director is taking the organization down the wrong road and must step in. When events are dramatic and their consequences are well understood, the determination to get on with things closes down the psychological space available for alternative solutions.

Preferred Intervention Style. The will and energy for change are in place; leaders have only to provide a credible way to move forward and demonstrate self-confidence and belief in their staffs.

There is a limit to responsive states of readiness. In general, people and organizations in responsive states do not feel threatened. They do not anticipate radical change, either in the form of a dramatic restructuring or of a paradigm shift in the way the organization’s mission, strategies, or operations are conceived. Transformational experiences grow from instability or from small powerful new forces in an organization’s life that, with support, have the capacity to pull the organization into entirely different ways to perform their work. Therefore, when the utilization of responsive states proves either ineffectual or not helpful enough, leaders may turn to unstable states of readiness.

Using Instability

Physical scientists have demonstrated that systems in disequilibrium are vulnerable to change. This observation is equally true for people and organizations. Individuals, groups, and organizations, when disrupted, can find themselves confused, anxious, sometimes feeling helpless, and ready for relief. When confusion exceeds our ability to cope with even ordinary matters, we reach out for almost any way to get oriented — even if what we find is new and unfamiliar. We become alert for people who can help us. We pay attention to thoughts, strategies, and feelings that had been buried and forgotten during stable times. Or we take risks and behave in uncharacteristic ways, as when crisis brings out the best in some individuals and organizations. Unstable states provide the soil in which forays grow.

Physical scientists have demonstrated that systems in disequilibrium are vulnerable to change.

Where, you may ask, do unstable states come from, and do they come frequently enough for impatient planners to make use of in designing interventions? They do. Leadership changes, reorganizations, and challenges from the marketplace, for example, periodically throw people into states of confusion, anxiety, panic, and crisis — and get them wondering if their way of doing business is viable, or even if they are in the right business. During the course of a given three-year period, every organization is likely to question itself at a basic level.

Like responsive states, unstable states range from mild to very intense:

Confusion and Disorientation. Leaders and staff become confused and disoriented at work more often than they let on. Rapid growth, for example, may render informal management incompetent. Funding agencies may insist on better financial controls and more sophisticated information systems. As details fall between the cracks, as they often do when grassroots and entrepreneurial organizations grow, staff may lose confidence in themselves and their leaders. They are no longer new and able to get by on enthusiasm, effort, and innovation, but they don’t yet know how to reorganize in a more professional way. At such junctures, leaders are often unclear how to lead, and staff do not know how or who to follow. Confusion reigns.

Preferred Intervention. It is often helpful to name and affirm the confusion, framing it as a natural consequence of organizational change and growth and noting that it can be a source of energy and creativity. People will feel a strong desire to reestablish order. If the new order can incorporate adaptive ideas and if the urge for order helps the organization push towards a more coherent way to work, then the confusion will have served a great purpose.

Anxiety. Anxiety combines confusion with worry. Organizational problems are personalized, and we take them home. Problems remain somewhat vague, unfocused. The nature of anxiety is that it lacks a clear object. Anxiety draws people inward, away from colleagues, realistic evaluation, and collaboration.

Preferred Intervention. First, acknowledge the anxiety and name it. Second, encourage creative management that breaks the rules of business-as-usual. Third, work toward clearly defining the problem and potential solutions. Coming up with a rough version of a new strategic plan, one that people believe will lead them out of their troubles, is among the best ways to alleviate anxiety and realign the organization.

Panic and Crisis. There are times in organizational life when people panic, become fearful and frenetic, grow irrational, and lose their capacity for practical problem solving. Panic can be contagious. It can begin with one or two people, with one team or unit, and spread to others like grassfire while leaders — if they haven’t initiated the panic or been contaminated themselves — look on helplessly. Similarly, organizations can go through an identity crisis. They are changing so rapidly — through growth, change of services, change of location, change of leadership — that they no longer know who they are, and they cannot utilize their accustomed responses to situations. They feel awkward, inept — and, as a result, they act that way.

Preferred Intervention. Leadership needs to step forward and normalize the process. The challenge for leaders is to remain calm, to share both practical and impractical thoughts that can become the seeds of creative solutions. Besides normalizing and stating the potential in such moments, they must contain the panic. Strong leadership is required from someone who is not overwhelmed, who has perspective, who has watched groups and organizations enter — and leave — such crises several times before and come out better for it. The benefit is that organizations can become transformed, because the extreme disorganization created by panic loosens all patterns and opens the door to radical new patterns of experience.

Readiness in the System

Readiness is not a character trait or a quality that resides in others. A person can be ready to change in one situation or with one particular person and not with others. Context determines readiness as much as any particular quality of determination, urgency, openness, or vulnerability. If two people are joined in their urgency, for instance, they are more likely to move than if one is urgent for change while the other is bored, or if the other feels compelled to defend the status quo.

We have to be prepared to meet the readiness of others when and where it emerges. There’s no point in asking advice from someone who is prepared only for resistance. There isn’t much value in taking chances to leave familiar shores if others are made nervous by risk, instability, heated discussion, or intimacy. We have to engage and encourage the potential inherent in the readiness of others to change.

Creating Readiness

While we generally can find at least one of the three states of readiness in an organization, this is not always the case. Yet even in these situations, an opportunity remains. The patterns that hold a system in place and make it resistant to change can be disrupted. By disrupting ingrained patterns, we can generate states of readiness.

LEVERAGING READINESS

This chart is designed to help leaders decide how to move from utilizing one type of readiness to others. The order is based on (1) moving from the least to most intrusive and (2) emphasizing change that is invited or native to a system we intend to change.

For example, leaders can disrupt patterns of thinking. They can demand new levels of performance and can challenge assumptions. Similarly, dialogue groups and T-groups frustrate easy, rational modes of thought and push participants, first toward confusion (unstable states) and then toward more creative modes of thinking (forays). A similar experience occasionally takes place with particularly compelling speakers or inspiring leaders, who first connect with their audiences through shared ideas and experiences and, once the audience is rapt, lead them to entirely unexpected conclusions.

Further, leaders can disrupt the behavioral field. By asking a group of employees to rotate through each other’s roles, for example, a leader can create confusion (unstable states) as well as help workers broaden their appreciation of each other’s activities. The confusion then sets the stage for creative thinking about roles and collaboration. In some firms, the process is called “walking a mile” (in someone else’s shoes). When we restructure teams, committees, departments, and work processes, old patterns of behavior and cognition are similarly disrupted.

A Decision Sequence

We have developed a thought sequence to help leaders decide how to move from utilizing one type of readiness to others. The order is based on two principles: (1) moving from the least to the most intrusive; (2) emphasizing change that is invited or native to a system we intend to change (see “Leveraging Readiness”).

- Identify and Support Forays. Forays are the most natural to people, so they offer the best chance of long-term success (see “Forays: A Case Study”). If, for some reason, you can’t find forays to support or your support doesn’t bring about substantial change, turn to responsive states.

- Address Responsive States. The interventions here are straight-forward and simple: generally, provide information and guidance. Because people are curious or receptive, you have been invited to intervene; there is little to lose. If worst comes to worst, you will be ineffective. Don’t push. Pushing will create resentment and control struggles.

- Sustain Unstable States. Remember, you don’t have to create crises. The natural ups and downs of organizational life often create small and large experiences of instability and confusion.

- Disrupt Patterns of Thought, Behavior, and Feelings That Inhibit Change. The purpose of such disruption is not to force change — you can’t impose beliefs or behaviors — but to open gaps in patterns that permit people to learn and grow.

Changing Ourselves

Changing organizations always requires changing the people who work in them. Leaders, like others, have become integral parts of an organization’s stable patterns of thought, behavior, and feelings. Being part of the patterns presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is in the difficulty in personal change — gaining the perspective to see oneself in behavior and having the will to utilize that perspective to change oneself.

Changing oneself represents one of the most powerful tools available to the leader as an agent of organizational change. Leaders are obviously important in organizations, particularly because everyone observes their activities. When the leader’s action is out of character or a little unusual, people try to interpret it. The interpretation goes on internally — “What does this mean for me?” — and externally, as people talk in corridors, at lunch, in meetings.

When leaders change, there is often a ripple effect. One person changes, and that influences another and yet another. Observing these changes, the leader may adjust again. In other words, the leader’s initial change represents a foray. When others change in response and new patterns are built, then the foray has pulled the organizational system into a significant transformation.

Whenever leaders find themselves at an impasse with their staffs, changing their own behavior can set in motion such chains of events. A leader’s changes tend to destabilize the culture and processes of work, unfreezing stuck patterns and making reorganization possible. At the point where the organization grows unstable, each of the interventions we have discussed above becomes workable. Forays can be supported. Curiosity, receptivity, and even determination to change will emerge, presenting opportunities for leaders to introduce or reinforce the strategic directions around which alignment is built.

Many leaders plan and implement change efforts with hardly a thought to the readiness of their employees. They may assume that persuasion and reason will win the day. Or rather than picking their moments, leaders may try to create a permanent state of readiness for change in a negative way, by declaring that “only the paranoid survive,” or in a positive way, by striving to create a “learning organization.” But these approaches are likely to encounter resistance, either open or more subversive forms. By becoming aware of the different states of readiness and leveraging them, leaders widen their options and enhance their chances. Holding to the simplistic notion that “organizations are either ready or not ready for change” is to miss the truth — leaders can leverage readiness that exists everywhere.

FORAYS: A CASE STUDY

Marston and the consultant developed an elaborate plan to broaden and rationalize decision making both at corporate headquarters and clinics. The plan included, among other things, the development of cross-functional teams at the executive level and in the management of the clinics.

As they began to implement these plans, the consultant remained alert to developments at WHI — forays — that would enhance progress. That was fortunate because the CEO at first had great difficulty delegating management and decision-making capacities to the newly forming teams. Much of the progress eventually emerged through the leveraging of small changes, somewhat outside of the CEO’s main concerns.

Over time, a foray was identified — reengineering in finance. The reengineering process introduced a basic change in the way business was conducted. Decisions had been taken either by the CEO alone or by senior managers, in consultation with the CEO. They tended to be rapid, impetuous, sometimes brilliant, and often disruptive to organizational processes and culture as well as to the individual lives of employees. Reengineering emphasized careful, lengthy analysis of data and processes, and elicited the opinions of many middle-level managers from several departments. Thus, the foray in reengineering the finance department processes represented a paradigm shift from an entrepreneurial to a professional management style, with a cross-functional, team-oriented approach.

Eventually, another foray emerged — a management intervention in one of the clinics — and one was generated — the development of an executive team. As these initiatives were sustained and extended, the professional, analytical work style represented by the forays became the norm at WHI. The organization found that, as small changes begin to build, this bottom-up method generates a great deal of excitement — a key element in the successful leveraging of forays.

Barry Dym is an organization development consultant and executive coach, with an emphasis on change management, strategy development and implementation, and leadership and management development. He is the author of four books: Leadership in Nonprofit Organizations (coauthored with Harry Hutson), Leadership Transitions, Couples, and Readiness and Change in Couple Therapy. Barry was the founder and executive director of two organizations.

Harry Hutson is a leadership and organization consultant whose practice focuses on the human side of strategic change. He designs and leads systemwide planning events, results-focused workshops, and team-building exercises; in addition, he provides individual coaching for executives. Harry has served for many years on the board of directors of the New England Center for Children.

An expanded version of this article appears in Leadership in Nonprofit Organizations (Sage Publications, Inc., forthcoming).