There’s a tempest brewing in the American workplace. The graying of the vast baby-boomer generation, cultural misconceptions about aging, and an impoverished sense of how to improve the situation have created the prospect of a head-on collision between a group of people who want to work and organizations that have no satisfying place for them. This issue is particularly relevant now, when the robust economy and historically low unemployment rate have left many organizations scrambling to hire and retain qualified workers. Unless we act wisely and view this issue as a systemic — rather than an individual or a group — problem, the failure to better utilize and integrate older workers into our companies may seriously damage productivity and organizational effectiveness throughout the corporate world.

The Baby Boomerang?

According to the most recent U.S. Census, the 76 million children born between 1946 and 1964 — the so called “baby boomers” — are turning 50 at the rate of one person every eight seconds. The boomers now make up slightly more than half of the working population. Because of the sheer size of this demographic group, the average employee age is rapidly rising to about 40.

As the first wave of this generation begins reaching 55 in 2001 and heads toward retirement, the workforce could lose substantial numbers of experienced workers from all walks of life. But most boomers have neither the inclination nor the financial means for early retirement. According to a recent study, 80 percent of those born between 1948 and 1965 expect to work past age 65. Compare that with the roughly 10 percent of the over-65 group who held jobs in 1998.

Organizations seem inclined to let many older workers drift into boredom and stagnation.

The declining value of Social Security and pensions lends fuel to many boomers’ anxious decision to keep on working. The U. S. Social Security Administration estimates that only 2 percent of the population will be financially self-sufficient when it retires, making work a necessity for most. And if Social Security runs out of money by 2030, as currently predicted, employment after 65 will become a necessity for a large number of people.

However, ample evidence exists that, over the last couple of decades, business has given up on many older workers – that is, those over 50, although in some industries, the “cutoff point” is even earlier. In spite of legal efforts to the contrary (culminating in the Age Discrimination and Employment Act), companies are inclined to let older employees go. Why? Because these organizations believe that their graying workforce is responsible for high salaries and medical costs, declining productivity, stagnating career pipelines, and morale problems. Even when older workers are kept on the payroll, they seldom have the chance to sharpen their skills through additional training. Organizations seem inclined to let many older workers drift into boredom and stagnation.

We have found that many senior employees in high-tech firms, newspapers, and insurance companies feel like “has beens.” But because they must work to pay their mortgages and send their children to college, many seasoned workers respond to the lack of opportunity for continued personal and professional growth by “retiring on the job” – they no longer approach their work with enthusiasm or commitment. Thus, they end up fulfilling the low expectations that their managers have for them.

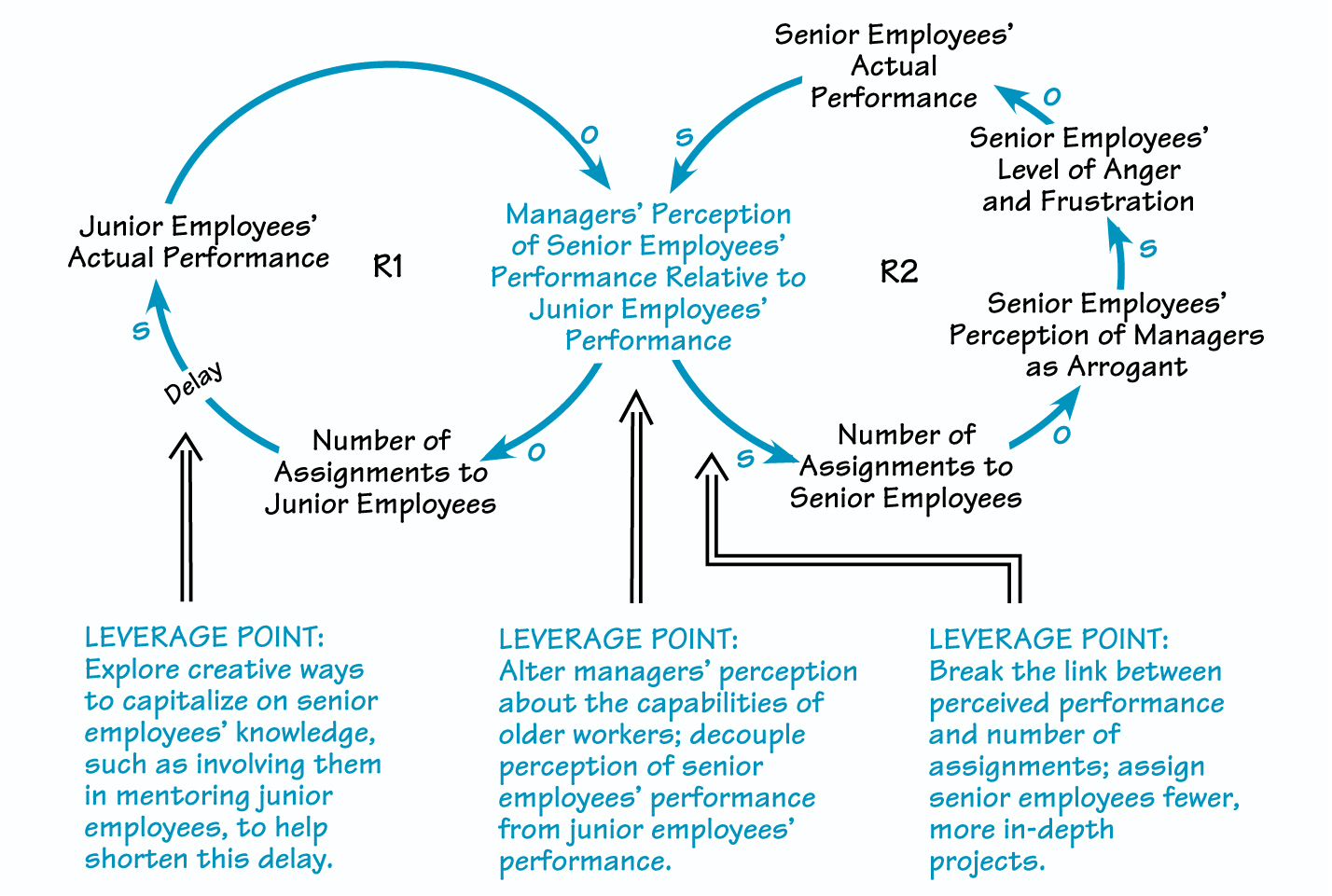

For example, in some news organizations, editors routinely favor younger reporters over more senior journalists, who are said to “lose their legs at 40.” As editors increasingly assign stories to younger reporters, the older reporters drift into unproductive marginality or frustrated opposition to their “arrogant and misguided” superiors (R2 in “From Perception to Reality”). This behavior further confirms the editors’ belief that the older reporters are “over the hill.” Over time, the individuals involved become stereotypes – the angry, ineffectual older reporter and the shallow young editor – playing out the roles that they had struggled to avoid. The caricatures seem so real that some editors refer stories to 23year-old reporters when a savvy, prize-winning, 55-year-old journalist, who has covered the field for 30 years, sits just 10 feet away.

FROM PERCEPTION TO REALITY

Companies lose, too, when they fail to capitalize on the knowledge and potential of their aging workforce. Older workers frequently have a level of experience, business acumen, and personal maturity that makes for conscientious effort, excellent customer and client service, and better decision-making ability than their younger peers. In many organizations, older workers know the customers and suppliers. They know the internal operating systems and the influence networks, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of the product line. Finally, they know the firm’s strategy, and they know how to get the job done. In short, they are the “institutional memory.”

In an era when knowledge management is a buzzword in every MBA program, the older worker is a knowledge holder and a wisdom maker. Getting rid of senior employees means the loss of insights and can lead to unproductive chaos. But companies overlook many possibilities for mobilizing the productivity of mature employees because of the pervasive myths about over-50 workers (see “Older Workers: Myths and Realities”). And, without an understanding of the dynamics that create — and perpetuate — these stereotypes, both older workers and those who manage them are destined to fall into them.

The Mismeasure of Age

People commonly joke about their lapses in memory by saying that they have “early Alzheimer’s” or that they have “creaky old bones.” But it’s no laughing matter when employers start to marginalize older workers because they are convinced that the post-50 crowd can no longer perform effectively. Research is beginning to demonstrate that mature workers are much more capable of all sorts of exertion than is commonly believed. Those who continue to work are the healthiest of all.

One study tells us that workers between 55 and 65 are as physically healthy as those between 45 and 55. They report to work as reliably as younger employees, and they perform virtually all but the most demanding physical tasks with comparable ability. A review of 185 research papers also found that older people may actually have higher motivation and job satisfaction than younger workers.

What about the idea that people slow down mentally? Longitudinal studies show that, unless a person has suffered a serious health problem such as a stroke or head injury, most of us sustain our intellectual functioning well into our 70s and beyond. Additionally, advances in medical and genetic technology promise to enhance the longevity and quality of life for many people who would have been forced into full retirement a decade ago. Taking the desire to work and the ability to work together, many people well past 65 are more than qualified for continued employment of all sorts.

So, why do so many companies routinely devalue the qualities that senior employees have to offer? Part of the problem may be that managers tend to compare older workers to younger ones. The flaw in this approach was dramatically pointed out by feminist researcher Carol Gilligan, when she challenged traditional theories of human development in her book In a Different Voice (Harvard University Press, 1982). She contended that Freud, Erikson, and Kohlberg, the gurus of developmental psychology, did not produce theories of human development but rather of male development. They neglected to take into consideration that men and women mature differently.

Likewise, in the workplace, older people are generally measured by standards that make them look less adequate than their younger peers, primarily by emphasizing mental quickness over depth of experience and physical stamina. This bias is reflected in the career development literature, which caps at about the age of 40, as though people and their careers could not develop further.

To counter this tendency to devalue the contributions that mature workers can make, we need to measure their capabilities and preferences on the basis of their distinctive qualities. We must view them as different but hardly less than youth. Measures should include older workers’ experience, personal and political savvy, and wisdom. Managers must take into account — and capitalize on — senior employees’ capacity to take the long view, and to keep small setbacks and slights in perspective. Organizations should place greater value on seasoned workers’ ability and inclination to nurture younger workers, and avoid placing them in direct competition with their youthful colleagues. Undoubtedly, there are many other capacities and mental attitudes that older workers possess that we have not yet associated with corporate productivity.

One way to deepen our knowledge of what workers in different age brackets have to offer is to learn about the stages of professional and human development. Students of the life cycle like Dan Levinson, an eminent authority in the field of adult psychological development, report that people in their 20s, 30s, and 40s focus on acting with autonomy, pursuing ambitions, and demonstrating competence. Those in their 50s, 60s, and 70s have a different set of requirements, involving the desire to appreciate their achievements, accept their limitations, and leave their mark on their families and communities. Older workers tend to focus on fine-tuning systems, procedures, policies, and methods so that they will stand up to the test of time. Their ambitions are likely to be consistent with what they know to be their strengths and competencies, so managers can generally rely on them to follow through on their commitments.

OLDER WORKERS: MYTHS AND REALITIES

Myth

As people age, they grow less capable

Mature workers cost more because of higher absenteeism and accidents

Older people don’t want to work

Corporations save by getting rid of older workers

Reality

As people age, more is gained than lost

Mature workers have better attendance and accident records than younger workers

Older people want to work differently

Corporations gain by retaining, redeploying, retraining, and revitalizing senior employees

Based on these interests and needs, many in the post-50 age bracket may no longer want to work the same job that they have been working and they may not want to put in as many hours. However, there are many roles that they would very much like to — and can — take on. To get the best out of mature workers, organizations need a strategy and structure that leverages the talents and responds to the developmental conditions and needs of this growing segment of the workforce.

New Concepts of Corporate Structure and Work

Once organizations see the value in retaining older workers, how can they take actions to keep these employees – and all of their insights and skills – involved in work? How can mature workers participate in a new sort of way, but still remain immersed in the systems that they know so thoroughly? It is admittedly hard to think of what to do with non-traditional workers within the standard corporate “pyramid.” From the traditional perspective, each employee climbs a ladder, peaks, plateaus, then declines. For example, journalists, dentists, and nurses are generally considered “to go downhill” around 40. The question remains: What can we do with these professionals for the remaining 25 years of their careers?

Management theorist Charles Handy’s conception of the new corporation opens the way to rethinking the place of older workers. Handy’s framework affords businesses the possibility of increased flexibility and cost savings by identifying three kinds of employees:

1. A core group of managers and skilled workers. These people lead the organization and provide its stability and continuity. They tend to be ambitious, totally immersed in their work and their organization, and very well paid for their efforts.

2. Key external resources hired on a contractual basis.These individuals and groups might provide outsourced accounting or legal services.

3. A project-based employee pool. These workers are loosely connected to the organization on a job-by-job basis, allowing the organization to expand, contract, and change shape, according to the demands of the market.

It is easy to imagine older workers in each of these three groups. The traditional core is generally filled by the most skilled, powerful senior managers. Many of those who “retire” return to their long-time employers as consultants and contractors, which offers them greater control over their time. The project-based employee pool provides even greater flexibility for employees who, later in their careers, may wish to labor intensely and then take prolonged vacations, or to work from their home offices instead of being burdened by demands for “face time.” The second and third functions also offer alternative career paths for parents of young children, children of aging parents, and individuals with health problems.

A basic ingredient of this approach is what Professor Lotte Bailyn of MIT refers to as the “disaggregation of work.” Our assumptions about what constitutes “working” are largely based on a model constructed during the industrial era. According to this view, work happens:

- in a particular place (in an office or factory)

- during a certain time frame (usually 9 to 5)

- for a certain amount of time (8 hours)

- in the context of certain social relations (i.e., with a particular group of people)

- with the use of preidentified technologies (i.e., technologies that are owned and approved of by the organization)

- to accomplish a specialized function or goal.

Bailyn and those on the leading edge of career development theory and practice recommend unpacking this cluster of assumptions about the nature of work for all employees.

Many private-sector companies and other organizations are already experimenting with these elements, separately and in combination, through flextime arrangements, telecommuting, intranet and Internet-facilitated group work, rotating work assignments, temporary work groups, and so on. Sources such as Fortune magazine’s annual listing of the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America” often include “best practices” that offer alternatives to the standard eight-hour in-office work day. These policies can easily be refashioned to address the needs and wants of older workers.

Working Wisely with Older Workers

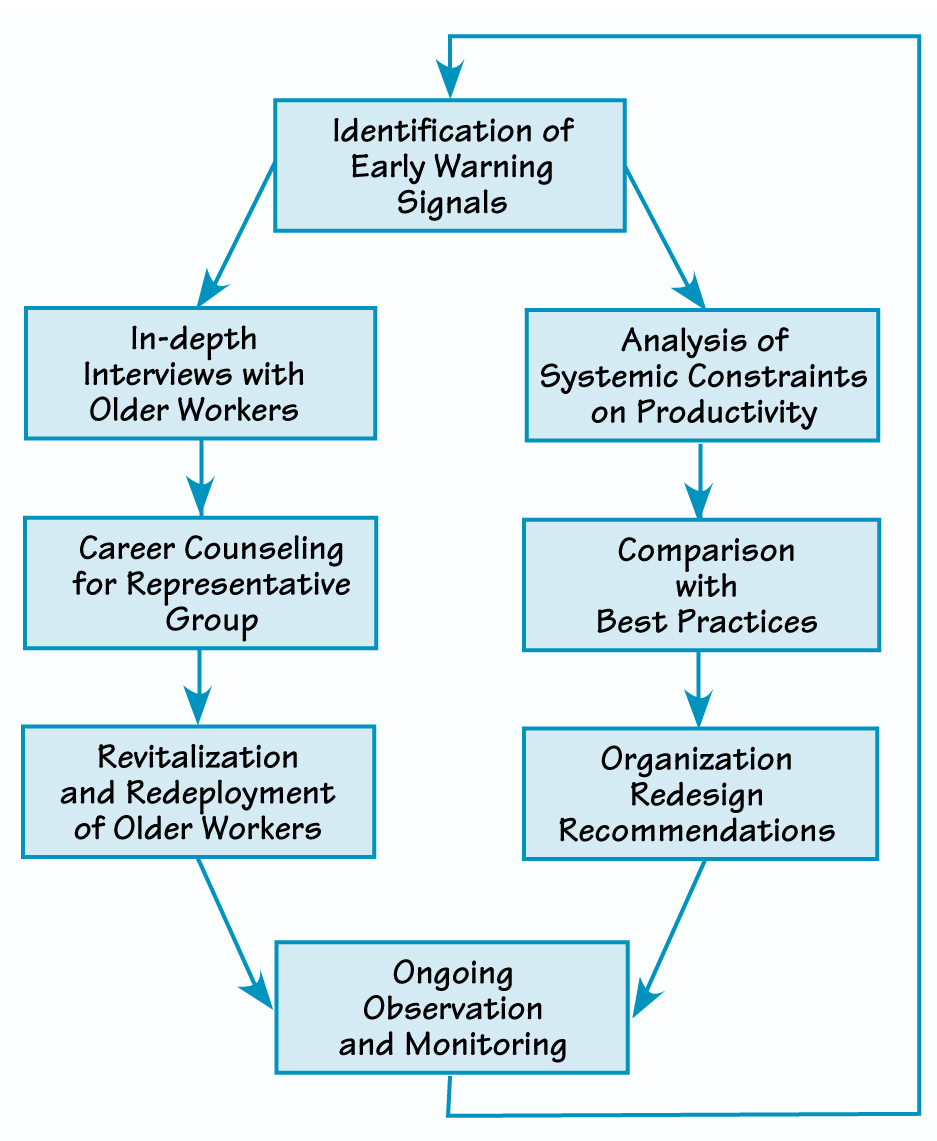

How can decision-makers help their organizations to break free from the negative stereotypes about older workers that inevitably become self-fulfilling prophesies? How can companies find ways to better utilize the knowledge and experience that this group possesses? We suggest the following steps (see “Steps for Leveraging the Older Workforce”):

1. Identify warning signs. Through informal conversation and interviews, determine:

- if a significant portion of the older workforce seems less than optimally productive,

- if there is considerable misunderstanding, miscommunication, and conflict between generations,

- if there is difficulty retaining skilled workers and experienced managers,

- if these problems are contributing to low morale in your corporation.

STEPS FOR LEVERAGING THE OLDER WORKFORCE

If the warning signs are present, take actions to address both individual and organizational issues, as follows:

2. Conduct in-depth interviews with older workers.

These interviews should focus on people who can be helped by organizational improvements, rather than on chronic poor performers or entrepreneurial self-starters.

- Explore workers’ present and past interests; their experiences of being underutilized, pressured, ignored, or marginalized; their emotions about their treatment within the organization; and their ambitions.

3. Explore systemic causes of the problem.

- Analyze underlying constraints on productivity and job satisfaction. For example, management may not keep up with the particular abilities and interests of older workers or may let them languish in boring and unchallenging positions. This analysis should derive from a combination of key informant interviews, conducted with a diagonal slice of the organization, focus groups, and a broad-based questionnaire. The tools of systems thinking — such as causal loop diagrams — can be useful here as well.

- Determine which formal and informal systems, cultural values, and organizational dynamics constrain and which enhance productivity and job satisfaction for mature workers and for workers in general.

4. Provide career counseling where needed.

- Offer counseling for older employees to determine how to redeploy or retrain them to revitalize their careers.

5. Compare the present situation with “best practices.”

- Identify best practices from other organizations that might work for you.

- Look for examples of excellence within your business that might be brought into service elsewhere in the company.

6. Design programs for senior workers to:

- Continue to upgrade their skills,

- Shift them into lines of work that capitalize on their old competencies but also demand new understandings,

- Use their experience through teaching, mentoring, or leading cross-departmental initiatives.

7. Develop organizational change strategies for implementing the recommended programs.

- Evaluate the organization’s core beliefs and culture to ensure that any new policies complement current management practices.

8. Once you’ve implemented the new programs, observe whether the corporate culture supports these changes over time.

- Determine if organizational and individual efforts have significantly increased the productivity and job satisfaction of older workers, as well as the productivity and morale of the entire corporation. You should continually be alert for the warning signs listed in step 1 and be willing to cycle through the steps again as needed.

Overcoming the “Pygmalion Effect”

We are all prone to think that what we see is true. Yet everyone knows that we each change according to the context we are in: home or work; friendly or unfriendly; familiar or unfamiliar; supportive or unsupportive; challenging or accepting. Like anyone else, older workers are more or less productive in different environments. The same people who look bored, uncommitted, or incompetent in contexts not geared to bring out their best can be excited, engaged, and extraordinarily skilled in settings that expect, require, and facilitate their performance.

In a well-known research project by Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson, published as Pygmalion in the Classroom: Teacher Expectation and Pupils’ Intellectual Development (Irvington Publishers, 1989), two teachers were presented with two groups of students of equal ability. One was told that the members of her class were very intelligent and talented. The other teacher was told that her class was mediocre at best. During the course of the year, the first group did well, and the other did badly. The power of expectations on people’s performance is almost impossible to believe, until you see the outcomes of studies like this one. Only by being vigilant and by creating structures that accommodate people’s differences can we overcome this tendency for perceptions to become realities.

So it is with older workers. Raise expectations, provide flexible working conditions, manage them according to their experience, skills, inclinations and wisdom — and they will produce far, far more than the stereotyped senior employee so prevalent in our imaginations. The public at large has a real stake in the success of initiatives that keep older workers at a high level of capacity. Even a 20-percent rise in productivity in the healthcare industry, which has a high percentage of workers over 50, would result in nearly a billion-dollar increase in revenues, efficiencies, and savings. This figure doesn’t include benefits in the form of innovations and quality initiatives.

Imagine the productivity increases that the corporate world would experience by making the best use of the hundreds of thousands of aging boomers on the payrolls. And also consider the society-wide toll that failing to provide meaningful opportunities for seasoned employees to continue contributing and supporting themselves financially may take. Fortunately, by retaining, revitalizing, and retraining the most skilled, savvy workers in the workforce, we can improve productivity — and people’s lives — well into the future.

NEXT STEPS

- Evaluate whether your organization or department exhibits any of the warning signs that older workers are being marginalized or underutilized.

- Find creative ways for junior and senior workers to mentor each other on-the-job. For instance, pair a younger employee with experience using the Web with a more established contributor who knows the ins and outs of project management

- Familiarize yourself with the dangers of perception, as illustrated in “From Perception to Reality”, and described in Pygmalion in the Classroom. How can managers avoid falling prey to stereotypes about certain groups of workers?

Barry Dym, PhD, is president of WorkWise, an organization that researches career options for workers over 50. He has 30 years of experience as an organizational development consultant, psychotherapist, author, and teacher.

Michael Sales, EdD, is a partner in New Context Consulting, where he has worked with a number of the leading thinkers in the field of organization development.

Elaine Millam, MA, is vice president of WorkWise and is a change leader who helps leaders focus on organizational health and well-being.