Caffeine Addiction

It’s 6:00 a.m. on a Monday morning. The alarm clock blares, jolting you out of bed. You shuffle down to the kitchen and grab a cup of fresh coffee. A few gulps and…ahh. Your eyes start to open; the fog begins to clear.

10:30 a.m. — time for the weekly staff meeting. “I gotta have something to keep me awake through this one,” you think to yourself as you grab a cup of coffee and head into the conference room.

By 3:30 p.m. you start to feel that mid-afternoon energy low, so you head down toward the crowded coffee machine for another cup. “I really gotta cut down on this stuff,” you comment to the guy behind you in line. He nods. “I’m a five-cup-a-thy guy,” he confesses. “I just can’t give it up.”

Addiction

For most of us, the word “addiction” conjures up images of alcoholism and drug abuse or more “acceptable” habits such as coffee drinking — dependencies which are rooted in physical and neurological processes. It is not usually viewed as a social or organizational phenomena. But from a systemic perspective, addiction is a very generic structure which is quite prevalent in both social and organizational settings.

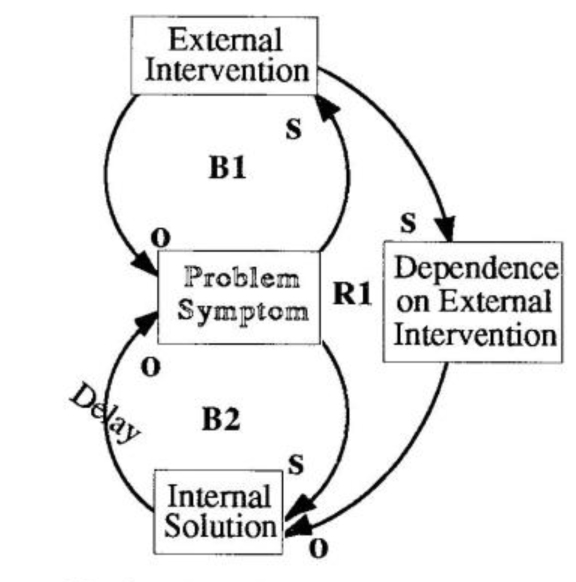

As a systemic structure, the “Addiction” archetype is a special case of “Shifting the Burden” (see “Shifting the Burden: The Helen Keller Loops,” September 1990). “Shifting the Burden” usually starts with a problem symptom that cries out for attention. The solution that is most obvious and easy to implement usually relieves the problem symptom very quickly. But the symptomatic solution has a long-term side effect that diverts attention away from the more fundamental solution to the problem (see “Addiction: A Special Case of ‘Shifting the Burden'”).

Addiction: A Special Case of 'Shifting the Burden'

What makes the “Addiction” archetype special is the nature of the side-effect. In an “Addiction” structure, a “Shifting the Burden” situation degrades into an addictive pattern in which the side-effect gets so entrenched that it overwhelms the original problem symptom — the addiction becomes “the problem.”

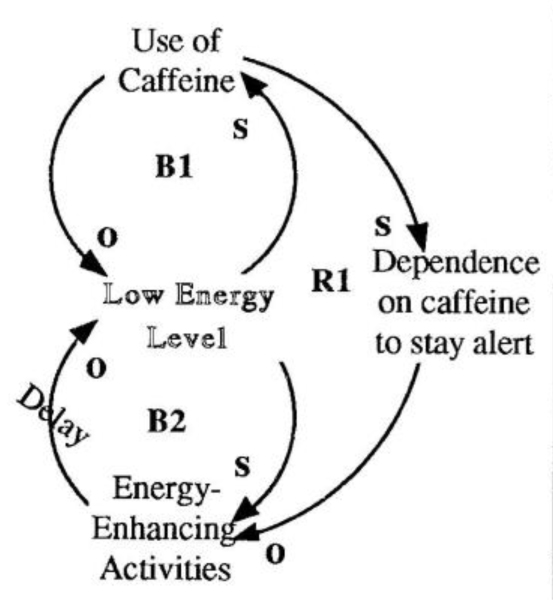

With coffee drinking, the problem symptom usually is that you feel tired (see “Coffee Addiction”). When you drink a cup of coffee, the caffeine raises your metabolism, stimulating the body and making the mind more alert. But in doing this, it forces your body to deplete its reserves of energy faster than usual. When the effects of the caffeine wear off in a few hours, you have even less energy than before. You feel sluggish again and reach for another cup of coffee to get a jump start. Over time, your body begins to rely on the caffeine at regular intervals in order to regulate your energy and metabolism.

Organizational Addictions

In organizational settings, addiction can take the form of a dependence on certain policies, procedures, departments, or individuals. The way we think about problems, or the policies that we pursue, can become addictions when we use them without consideration or choice, as an automatic knee-jerk response to a particular situation.

Hooked on Heroics

A common yet very subtle example of addiction in companies is “crisis management” — fire-fighting. Most managers say that they abhor fire-fighting because it wreaks havoc on normal work processes and makes it difficult to focus on the long-term. Yet fire-fighting is a way of life in most companies. Its pervasiveness and persistence is a clue that maybe it is part of an addictive structure.

Suppose you have a new product development project that has fallen behind schedule. The timing of its release is critical to its market success. In fact, the delays have reached crises proportions. You decide to make it a high priority project and assign a “crisis manager” to do what it takes to get that product out on time. This new manager suddenly has enormous flexibility in what he can do to get the product out. When the product is launched on time, he is touted as the hero of the day.

Hooked on Heroics

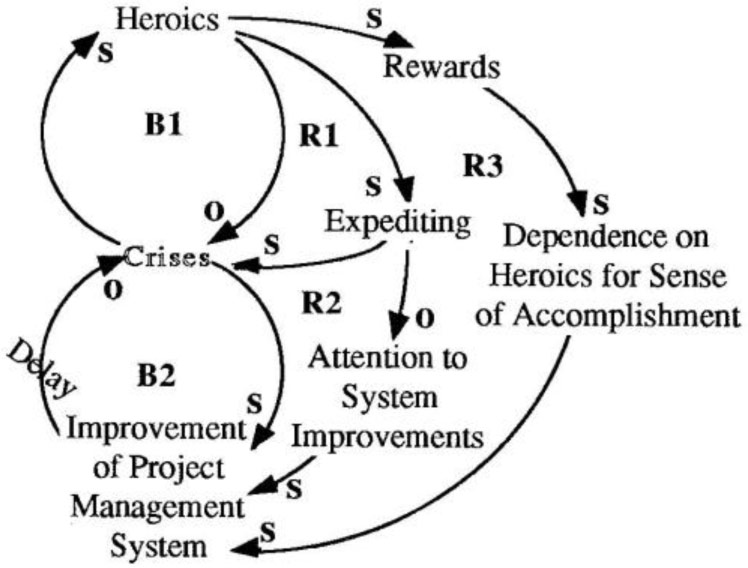

If we look at crisis management from the “Addiction” archetype, the symptomatic problem is the prevalence of crises that occur in the company (see “Hooked on Heroics”). When a crisis occurs, someone practices great heroism and “saves the day.” The problem is solved and the person receives praise for doing a fine job. But what happens to the rest of the organization in the meantime? Oftentimes the solution causes a lot of disruptions which form the seeds of the next problems and perpetuate the crisis cycle.

The insidious side-effect of crisis management is that over time, as crisis management becomes the operating norm, managers begin to become dependent on the use of heroics — the need to have recognition and a feeling of accomplishment in an otherwise paralyzing institution. Usually there are roadblocks to taking action in the company: formalities and rules that say “No, you can’t do this,” “You have to do it this way,” or “We don’t have the resources.” Suddenly when there’s a crisis, people are given tremendous freedom and leeway and are allowed to do what they couldn’t do before. Once it’s over, there is tremendous fanfare: the hero is rewarded or promoted. Over time, the company becomes addicted to continually creating crises, pulling the organization through tremendous turmoil, and creating new heroes.

Breaking the Addiction Cycle

To identify “Addiction” dynamics at work, use the “Shifting the Burden” archetype as a diagnostic to ask questions such as: “What was the addiction responding to?”, “Why did we feel a need to engage in this behavior or create this institution in the first place?”, and “What are the problem symptoms that we were responding to?”

“Addiction” structures can be much more difficult to reverse than “Shifting the Burden” because they are more deeply ingrained. Just as you can’t cure alcoholism by simply removing the alcohol, you can’t attempt a frontal assault on an organizational addiction because it is so rooted in what else is going on in the company.

If your company is addicted to fire-fighting, declaring that there will be no more heroics may be the worst thing you can do. If heroics were the only way your organization knew how to release the accumulated pressures produced by ineffective processes, ending that practice may lead to an eventual explosion or systemic breakdown. To break the addictive pattern, you need to explore what it is about the organizational system that created the crisis and left fire-fighting as the only option.

Innovation

Is there such a thing as a benign or innocuous addiction? One could argue that some addictions are worse than others, and some may not be bad at all. The fundamental problem with any addictive behavior, however, is that it can lead an organization to become very myopic. The addictive solution becomes so ingrained that no other possibility seems necessary. Preventing corporate addictions requires the ability to continually see choices in a fresh way — to shun habitual responses.

The challenge for the learning organization is to get all the members of the organization to continually look at things with fresh eyes. That’s the essence of discovery…and the essence of innovation.