In response to growing environmental and social equity problems, hundreds of private and public “sustainable development” initiatives have blossomed across the globe since the mid-1980s. Despite the increased activity, most experts would agree that progress toward sustainability has been, at best, modest. But why have so few organizations successfully adopted effective sustainability measures? And when companies do launch such efforts, why do so many plateau after a short time, fall short of making the jump from rhetoric to action, or even fail? To learn the answers to these questions, I spent three years researching how more than 25 public and private organizations have approached the issue of sustainability (for details about this study, see my forthcoming book Leading Change Toward Sustainability: A Change Management Guide for Business, Government, and Civil Society, Greenleaf Publications, UK).

Defining Sustainability

Before sharing what I found, let me define what sustainability means. Our current economic system is fundamentally linear in nature. It focuses on producing products and delivering them to the customer in the fastest and cheapest way possible. We extract resources from the Earth’s surface, turn them into goods, and then discharge back into nature the byproducts of this process as massive amounts of often highly toxic waste (which we call air, water, and soil pollution) or as solid, industrial, and hazardous waste (which we dispose of in landfills or burn in incinerators). After 200 years, this so-called “cradle to grave” production system has become firmly embedded in our psyches as the dominant paradigm.

However, there is an underlying problem with this model: It turns out that the Earth’s air, forests, oceans, soils, plants, and animals do not have the capacity to endlessly supply increasing amounts of resources, nor can nature absorb all of society’s pollution and waste. The field of sustainable development has emerged in response to the mounting ecological and social challenges stemming from the traditional economic paradigm. At its core, this new approach fundamentally transforms the linear model into a circular one — what design experts Bill McDonough and Michael Braungart call a “cradle to cradle” production scheme.

This revolutionary economic paradigm eliminates the concept of waste entirely, because goods and services are designed from the outset as feedstocks for future beneficial use. To achieve this outcome, companies harvest energy and raw materials without damaging nature or communities. Then, as McDonough and Braungart say in their book Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (North Point Press, 2002), “Products can either be composed of materials that biodegrade and become food for biological cycles, or of technical (sometimes toxic) materials that stay in closed-loop technical cycles, where they continually circulate as valuable nutrients for industry.”

Organizations such as Herman Miller Inc., an international producer of office furniture and services; Inter face Inc., one of the largest manufacturers of commercial floor coverings; and Henkel, a German company that makes a broad range of industrial, commercial, and consumer chemical products are adopting this “cradle to cradle” model. As a result, they are realizing major cost savings, reduced risks, and increased competitive advantage, along with significant social and environmental benefits. But unfortunately, few executives in other businesses grasp the fundamental paradigm shift that sustainable development requires. Blinded by long-held mental models, they fail to fundamentally alter the ways in which their organizations produce goods and services. They believe that sustainability simply involves better controls, marginal improvements, or other “efficiencies” within their existing, linear business model. These managers cling to the fallacy that traditional, hierarchical organizations can manage closed-loop, cradle-to-cradle systems.

Seven Sustainability Blunders

Thus, most organizations seeking to improve their management of environmental and socio-economic issues inevitably fall prey to one or more of seven key “sustainability blunders.” Becoming aware of how these blunders can undermine an organization’s efforts to mitigate its impact on the environment is the first step in creating a sustainable enterprise.

Blunder 1: Patriarchal Thinking That Leads to a False Sense of Security Organizations that struggle to adopt a more sustainable path invariably employ a patriarchal approach to governance. Employees do only what management orders, and the organization strictly follows government mandates. Employees and the organization as a whole seldom, if ever, go beyond the requirements of their “superiors.” No one meaningfully challenges the linear economic paradigm or mechanical organizational designs that control thinking. This is the most serious of the seven blunders, because it creates an addiction to the directives of higher authorities and an abdication of personal responsibility.

Blunder 2: A “Silo” Approach to Environmental and Socio-Economic Issues In most organizations, different functions, such as environmental and labor relations, are usually assigned to separate units. Executives see sustainability as yet another special program and don’t understand how it affects design, purchasing, production, and all other units. Because no single unit can identify all of the ways in which processes or products affect the environment or social welfare, the status quo is perpetuated.

Blunder 3: No Clear Vision of Sustainability

Organizations struggling to adopt a sustainable path usually lack clarity about what they are striving to achieve. Without a clear vision, they often assume that being in compliance with the law is the sole purpose of their policies. But compliance is a backward-oriented, negative vision focused on what not to do. It depresses human motivation. Sustainability is a forward-looking vision that excites people and elicits their full commitment and energy.

Blunder 4: Confusion over Cause and Effect

The prevailing mental models held by most executives lead them to focus on the symptoms, not the true sources, of sustainability challenges. Organizations spend millions to mitigate emissions and discharges, never recognizing that these are the results, not the causes, of their problems. Emissions and discharges stem from the ways processes and products are designed and the kinds of toxic materials, chemicals, and energy used to make them. Pollution controls temporarily mask these problems and keep organizations focused on managing effects rather than on designing out root causes.

Blunder 5: Lack of Information

People need a tremendous amount of clear and easily understood information to comprehend the downsides of the linear production paradigm and the benefits of the circular cradle-to-cradle approach. However, most organizations fail to communicate effectively about the need for and the purpose, strategies, and expected outcomes of their sustainability efforts. Trainings, sign postings, and a few scattered events are insufficient to convey what a commitment to sustainable development involves or why employees should participate.

Blunder 6: Insufficient Mechanisms for Learning

When employees are given limited opportunities to test new ideas, and when they receive few rewards for doing so, not much learning occurs. Organizations struggling to become sustainable rarely institute mechanisms that allow workers to continually test new ideas, expand their knowledge base, and learn how to overcome barriers to change.

Blunder 7: Failure to Institutionalize Sustainability

The ultimate success of a change initiative occurs when sustainability-based thinking, perspectives, and behaviors are embedded in everyday operating procedures, policies, and culture; for example, when an organization links bonuses, promotions, new hiring, and succession planning to performance on sustainability. However, few organizations have incorporated sustainability in their core policies and procedures. Until they do so, employees will remain unconvinced of their employers’ commitment to this crucial issue.

The Wheel of Change

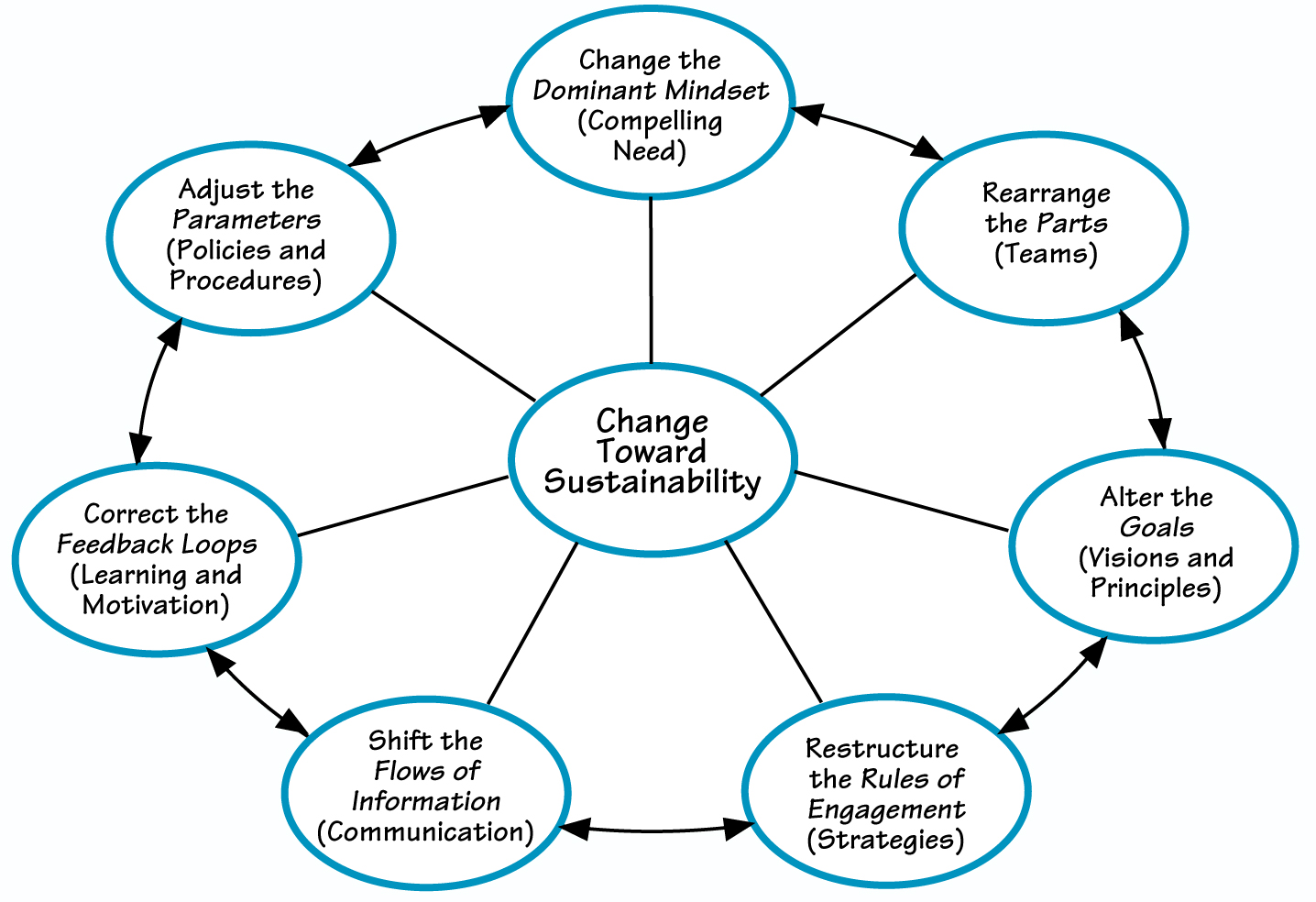

Although one or more of the blunders occur in most organizations, a small but growing number of early adopters are leading the way toward sustainability by successfully changing their traditional production and organizational paradigms. Their leaders grasp that deep-rooted cultural transformation is necessary to overcome the resistance inherent to the profound changes necessary to achieve true sustainability. Here are the interventions that successful change leaders use to resolve each of the seven sustainability blunders:

Intervention 1: Change the Dominant Mindset Through the Imperative of Achieving Sustainability

The false sense of security that people feel when they are in compliance with regulations must be undermined before employees will open themselves to circular cradle-to-cradle thinking and action. Disrupting an organization’s controlling mental models is the first — and most important — step toward the development of new ways of operating. Little change will occur if this step is unsuccessful.

An enlightened leader in a small organization can sometimes alter the controlling mindset by simply talking with senior executives, employees, and stakeholders. Tom Kelly, president of Neil Kelly Co., Portland, Oregon’s largest home remodeling firm, introduced sustainability principles to his employees and asked if they would like to apply them in their work. The workers said “yes.” The firm went on to manufacture the first interior cabinets certified by the Forest Stewardship Council and received the first LEED construction certification in the Northwest from the U. S. Green Building Council for its new showroom.

However, most organizations seem to require a major crisis to spur action. Senior executives at IKEA, a global furniture manufacturer, became committed to sustainability only after the company experienced a series of high-profile environmental and labor crises. Ray Anderson, chairman and former CEO of Interface, one of the world’s largest producers of commercial floor covering, became a convert after customers began to ask about the firm’s environmental policies. In the vast majority of cases, a relentless and compelling message from senior executives is required to make the case that safety from legal challenges, social protest, financial losses, customer defection, or environmental crisis can be achieved only by adopting a new business model based on sustainability.

Intervention 2: Rearrange the Parts by Organizing Transition Teams

Once business-as-usual thinking has been shattered, the next step is to rearrange the parts of the current system. Doing so requires the involvement of people from every function, department, and level of the organization — and key external stakeholders — in analysis, planning, and implementation. This “shake-up” is important because planners and decision-makers often surround themselves with likeminded people, do not trust the unknown, or may feel threatened by change. Consequently, they handle problems in the same way time after time. Changing the composition of groups brings fresh perspectives and ideas to the table. New people can see problems that the old guard couldn’t. They can also suggest different solutions because they are unconstrained by the dominant cultural paradigms.

The leading sustainability organizations shake up the status quo by organizing sustainability “transition teams” that develop new goals, strategies, and implementation plans. Over time, the composition and nature of the teams will change as people go deep into the organization to flesh out problems, break old thought patterns and perspectives, and align practices with sustainability. For example, the initial team may assess company policies and procedures and complete an audit of overall environmental and social impacts. Subsequent teams may be organized to apply the new approach within each unit and function. The most important step each team must take is to get clear about what it is striving to achieve, the role each person will play, and the rules they will follow to accomplish their mission.

Herman Miller Inc. established the Environmental Quality Action Team (EQAT) to “help the corporation through the muddy waters of environmentalism.” Once the EQAT was clear on its mission, it formed nine subcommittees, including the Design for the Environment team, which focused on formulating sustainable products. This team produced the Ergon 3 office chair, which is made with 60-percent recycled content. Ninety-five percent of the materials in the chair can be recycled or reused. Other subcommittees have identified reductions in energy use and packaging that have saved the company millions of dollars.

Intervention 3: Change Goals by Crafting an Ideal Vision and Guiding Sustainability Principles

The third key leverage point for cultural change toward sustainability is to alter the organization’s goals. Change the goals, and different kinds of decisions and outcomes will result. Doing so requires a clear depiction of the new ends the organization seeks to achieve and guidelines for how decisions should be made to achieve them.

The leading organizations use “ends-planning” (sometimes called “backcasting”) to craft an exciting vision of how they will look and operate when they are a sustainable enterprise. Compelling visions are felt in the heart and understood in the mind. Organizations can then adopt principles that support the vision and provide a roadmap for decision-making; for example, by deciding to use materials that are extracted from nature in ways that do not degrade the surrounding ecosystem.

Herman Miller’s vision is “to become a sustainable business: manufacturing products without reducing the capacity of the environment to provide for future generations.” The company uses The Natural Step and Bill McDonough’s “Eco-effectiveness” principles (www.mcdonough.com) as the guiding frameworks for its sustainability initiative. Scandic Hotels adopted a vision of achieving environmental sustainability by “moving from resource wasting to resource caring.” This vision led them to realize that ecological sustainability is not a cost but a source of profits and competitive advantage.

Intervention 4: Restructure the Rules of Engagement by Adopting New Strategies

After the organization has adopted new purposes and goals, the next intervention involves altering the rules that determine how work gets done. Doing so involves developing new strategies, tactics, and implementation plans. The organization should come up with both operational and governance strategies in this process. The enterprise as a whole must answer four questions: (1) How sustainable are we now? To respond, you need baseline data describing where and how the organization’s processes and products currently affect the environment and social welfare. (2) How sustainable do we want to be in the future? Adopt clear goals and targets that clarify when the organization expects to achieve certain milestones. (3) How do we get there? Design operational and governance change strategies for achieving the goals and targets. (4) How do we measure progress? Adopt credible sustainability indicators and measurement systems to quantify progress toward goals and facilitate adjustments.

In the early 1990s, the Xerox Corporation adopted the vision of becoming “Waste Free.” The vision catalyzed profound changes in operations all the way back to the initial designs of major product lines. The strategies required decentralized decision-making, which helped to dramatically increase employee morale and commitment. By the end of 2001, the initiative had led to the reuse or recycling of the equivalent of 1.8 million printers and copiers. It also resulted in several billion dollars of cost savings, as well as dramatic improvements in all environmental areas.

Intervention 5: Shift Information Flows by Tirelessly Communicating the Need, Vision, and Strategies for Achieving Sustainability

Even when all other interventions have been successful, progress will stall without the consistent exchange of clear information about the need for the sustainability initiative and its purpose, strategies, and benefits. Effective communication engages people at an emotional level. Sustainability visions and strategies become internalized as people ponder what these changes will mean to them personally. Transparent communication opens the door to honest understanding and sharing.

The leaders at Interface instituted a comprehensive information and communication program to engage employees and stakeholders in sustainability efforts. Now, environmental issues are discussed at almost every staff meeting, in executive retreats, and via internal communications. Board chairman Ray Anderson says, “Sustainability has become the language of the company.”

Intervention 6: Correct Feedback Loops by Encouraging and Rewarding Learning and Innovation

Even with excellent strategies, obstacles will surface. To overcome the barriers to change, the organization must alter its feedback and learning mechanisms so that employees and stakeholders are continually expanding their skills, knowledge, and understanding. The adoption of new learning mechanisms leads to wholesale changes of traditional feedback systems that are oriented toward maintaining the status quo.

The leading organizations provide accurate feedback on progress and setbacks, and rewards for those willing to experiment and learn. Henkel adopted a strategy to differentiate itself from its competitors based on its ecological and social performance. The company believes that “Innovation is the key to sustainability.” To encourage innovation, the company gives out “Henkel Innovation Awards” to employees who develop sustainable new products. The award includes public recognition via press releases and in company newspapers. Henkel also keeps a database of successful ideas generated by employees that is available to its workers worldwide.

Intervention 7: Adjust the Parameters by Aligning Systems and Structures with Sustainability

Because internal systems, structures, policies, and procedures should not be altered until the right kind of thinking and behaviors have been identified and implemented, changing these parameters is the last step in the change process. At the same time, the effort never actually ends at this stage. Change toward sustainability is iterative. The “wheel of change” must continually roll forward. As new knowledge is generated and employees gain increased know-how and skills, the organization needs to continually incorporate new ways of thinking and acting into how it does business.

Patagonia, the U. S. retailer of outdoor gear and clothing, explicitly seeks to create a culture that values protection of the environment and of communities. Raises, bonuses, promotions, and succession planning all depend on the level of contribution employees make to the firm’s core values of environmental protection and social equity. IKEA has followed a similar course. Says Thomas Bergmark, Social Responsibility Manager, “No one has been promoted to the senior management level who does not have a strong commitment to these issues. Before we engaged in sustainability, there were managers who did not take environmental and social issues to heart. These managers are no longer at IKEA. We take great care to get the right people promoted.”

The “Wheel of Change Toward Sustainability” shows how the seven interventions interact to form a continuous reinforcing process of transformation toward sustainability.

Sustainable Governance

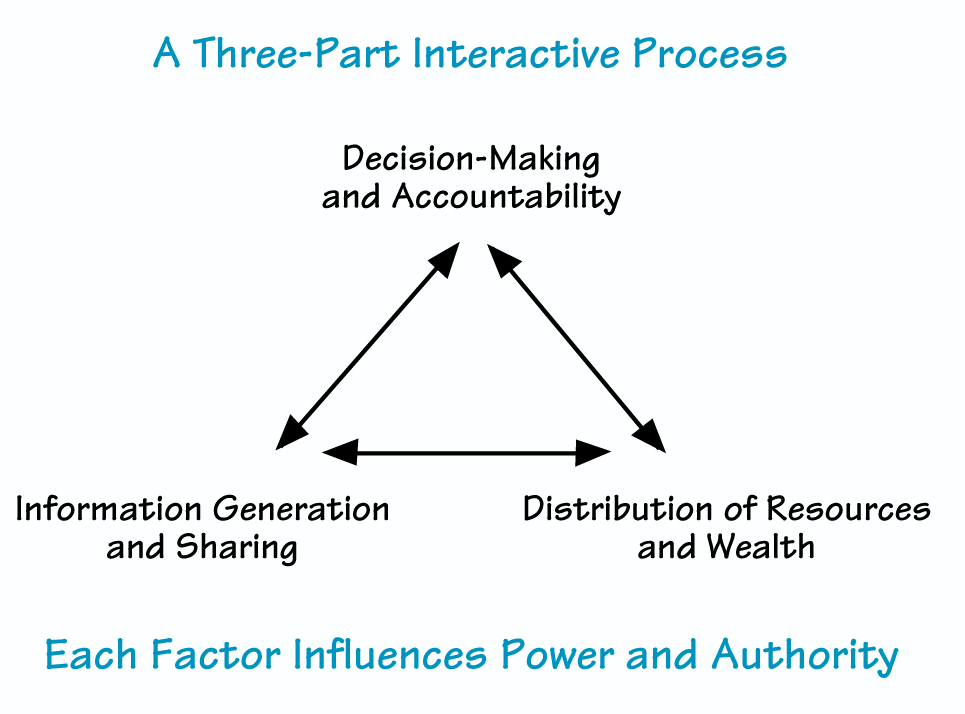

Many leaders have found that changes in governance provide the greatest overall leverage for facilitating the successful introduction of the interventions outlined above. What is governance? The Journal of Management and Governance says, “Governance . . . includes the modes of allocating decisions, control, and rewarding rights within and between economic organizations.” In other words, governance systems shape the way information is gathered and shared, decisions are made and enforced, and resources and wealth are distributed. These factors guide how people perceive the world around them, how they are motivated, and how they exercise their power and authority (see “Sustainable Governance Systems”).

The organizations leading the way toward sustainability tend to view all of the people that are affected by their operations — internal members as well as external stakeholders — as important parts of an interdependent system. Their leaders understand that every component of the system must be fully engaged and must function effectively for the whole to succeed. In order for this to be possible, power and authority must be skillfully distributed among employees and stakeholders through effective information-sharing, decision-making, and resource allocation mechanisms.

WHEEL OF CHANGE TOWARD SUSTAINABILITY

This model of governance is much more sustainable over time than a patriarchal approach, because as a natural output of the process, employees and other stakeholders have a high level of commitment and involvement. With the proper purpose, vision, and guiding principles, a new production model and organizational paradigm evolves that works to eliminate environmental and socio-economic problems and create business opportunities.

Sustainable governance systems have five dominate characteristics:

1. They follow a vision and an inviolate set of principles focused on conserving the environment and enhancing socioeconomic well-being. Every system has a purpose that is the property of the whole and not of any particular part or person. Sustainability holds equal — or greater — footing with the goals of profitability or shareholder value.

2. They continually produce and widely distribute information necessary for expanding the knowledge base and for measuring progress toward the core purposes. A system of feedback mechanisms produces and widely disseminates timely and credible environmental, social, and financial data to provide the information needed for continued learning and improvement.

SUSTAINABLE GOVERNANCE SYSTEMS

3. They engage all those affected by the activities of the organization. Sustainable governance systems involve in planning and decision-making all those affected by the organization, including employees from all units and functions, as well as key stakeholders such as suppliers, investors, distributors, and community, environmental, and labor organizations.

4. They equitably share the resources and wealth generated by the organization. By spreading the return on investment among employees and stakeholders and by equitably distributing resources such as staff, time, and capital to internal units, leaders ensure that all participants give the enterprise their full engagement and support.

5. They provide people with the freedom and authority to act within an agreed-upon framework. Clearly defined, mutually agreed-upon goals, rules, roles, and responsibilities result in clear strategies and implementation plans. Power and authority are decentralized, and people have both the freedom and the responsibility to act.

None of the leading organizations I reviewed can be considered truly sustainable yet. Each is plagued by inconsistencies between their ideal vision and current practices. The early adopters acknowledge that they have just begun the journey to sustainability. But they have all implemented most, if not all, of these principles of governance. The organizations all describe and apply the principles in their own unique ways. But no matter how they are articulated or employed, these tenants provide the governance structure necessary for the long journey to sustainability.

In addition to the focus on governance, leading organizations are blessed with — or take explicit steps to develop — exemplary leadership at the top and throughout the enterprise. It is not possible to initiate or sustain the tremendous transformation required to become more sustainable without exceptional leadership. Thus, good governance and leadership are the two hallmarks of successful change toward sustainability.

Organizations that apply these interventions and make the transition to cradle-to-cradle production and systems-oriented organizational paradigms are certain to be the big winners in the future. Pressure will only increase from consumers, civic groups, and the financial markets for improved environmental and social performance. Executives who believe that these demands will fade or be deflated by shifts in environmental, public health, or labor laws may experience short-term relief from these pressures. In the long run, however, recalcitrant organizations will experience a backlash that may threaten their very existence. The successful leaders of the future will be those who have adopted a more sustainable model of conducting business.

Bob Doppelt is executive director of the Center for Watershed and Community Health, a sustainability research and technical assistance program affiliated with the Institute for a Sustainable Environment at the University of Oregon. Doppelt is also a principal with Factor 10 Inc., a sustainability change management consulting firm.

NEXT STEPS

- Determine the production model and organizational paradigm that control your enterprise through a survey or discussion.

- Identify which “sustainability blunders” plague your organization. Engage in honest discussion about how the controlling mental models that perpetuate the blunders affect performance and lead to environmental and/or related socioeconomic crisis.

- Assess your sustainability change strategy to determine which of the seven interventions may need expansion or renewed focus and attention.

- Compare your governance system to the principles of sustainable governance. Look for ways to reinforce those aspects that support sustainable governance and adopt new mechanisms as needed.