Our efforts to understand and intervene in organizational events have a persistent bias: to interpret phenomena from a personal framework. In other words, situations are to be understood in terms of the needs, motivations, temperaments, personal styles, values, and developmental stages of one or more of the individuals involved. And if the diagnostic lens is personal, then it follows that the interventions will also be personal: fix, fire, demote, replace, or suggest coaching or therapy for one or more of the parties.

I suggest an often overlooked lens that provides a deeper understanding of these phenomena and a range of more

TEAM TIP

Use an understanding of “context” to overcome the tendency to assign blame when problems occur.

effective leadership strategies. This is a person-in-context lens in which phenomena are understood as the interactions of individuals and groups with the systemic contexts in which they and others exist. When we fail to recognize context, events are misunderstood and energies misplaced. A missing leadership competency is seeing, understanding, and mastering the systemic contexts in which we and others exist.

In this article, I describe the consequences of blindness to context and the productive possibilities we derive from context sight. The first main section describes four common system contexts: Top, Middle, Bottom, and Customer. The second section discusses the four contexts as they apply to individuals and the third as they apply to groups. In both sections, I describe familiar scenarios that result from context blindness and produce personal stress, strained or broken relationships, and diminished organizational effectiveness. I also lay out some principles for seeing context and describe the positive difference that seeing context can make for leaders and others in organizations.

The fourth main section of the article presents a case that illustrates the limitations of personal orientations while demonstrating how seeing contexts deepens our understanding of situations and reveals more comprehensive and productive leadership strategies.

Seeing, understanding, and mastering context is an essential leadership competency. There is a difference between knowing that people operate in different contexts and experiencing relationships with people from different contexts in the day-to-day turmoil of leading modern organizations. I end with a discussion of the implications for leadership development.

Four System Contexts

A PERSON IN THE TOP CONTEXT

This section describes four common system contexts: Top, Middle, Bottom, and Customer (Oshry, 1994). This is not to imply that these are the only contexts in which people function, but these four are essential to our understanding of organizational interaction, and they are the four that I know very well from my work over the past forty years with both the Power Lab (Oshry, 1999) and the Organization Workshop, both described on page 4. What is important to understand is that Top, Middle, Bottom, and Customer are not just hierarchical positions; they are conditions all of us face in organizational interaction, conditions we move in and out of from event to event. So in that sense, all of us are Top/Middle/ Bottom/Customers.

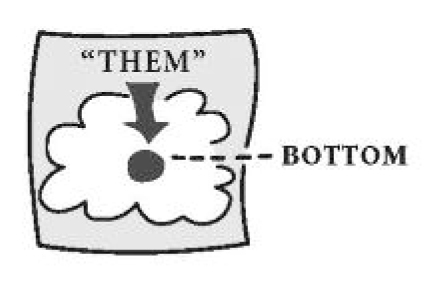

- The Bottom Context: Vulnerability. We are in the Bottom context (“A Person in the Bottom Context”) of vulnerability whenever we are on the receiving end of decisions that affect our lives in major or minor ways. Plants are shut down, health and retirement benefits are changed, restrictive governmental regulations are put in place, new initiatives are instituted, current initiatives are abandoned. All of this happens to us without our involvement.

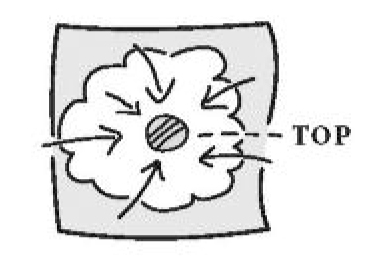

- The Top Context: Complexity and Accountability. We are in the Top context (“A Person in the Top Context”) whenever we have been designated responsible for a system or piece of a system — whether it is the organization as a whole, a division, unit, task force, family, project, team, or classroom. The Top context tends to be one of complexity and accountability: lots of inputs to deal with, difficult issues, issues from within and without the system, issues that aren’t dealt with elsewhere float up to you, and complex decisions must be made regarding the form, culture, and direction of the system. Whenever we are in that Top.

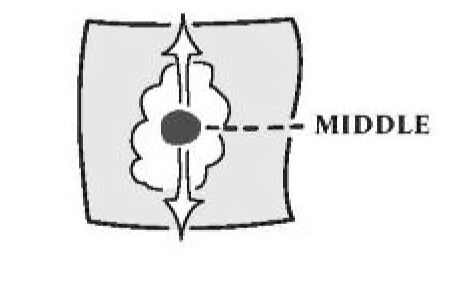

- The Middle Context: Tearing. We are in the Middle tearing context (“A Person in the Middle Context”) whenever we are pulled between the conflicting needs, demands, and priorities of two or more individuals or groups. We are Middle between our work group and our manager, between a spouse and a child, between supplier and manufacturing, between our executive group and the board, between one executive and another.

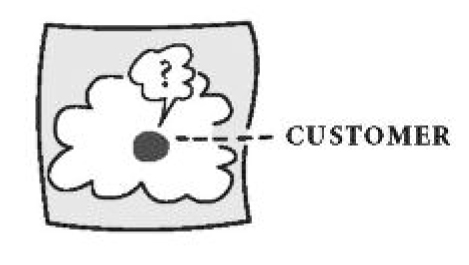

- The Customer Context: Neglect. We are in the Customer context of neglect (“A Person in the Customer Context”) whenever we are looking to some individual or group for a product or service that we need in order to move on with our work, and that product or service is not coming as fast as we want, at the price we want, or to the quality we had hoped for.

- ‘‘Arrogant’’ Tops. We may have a brilliant idea for organizational improvement. We send it to Top and await an acknowledgment, maybe even a promotion. To us, this is a great idea with potential for increased organization effectiveness. But to our Top, struggling to survive in this world of complexity, it may be just another complication in an already complex world. A week goes by with no response from Top. Two weeks. Nothing. Our reaction: It’s those arrogant Tops again! We get mad, we withdraw, and we lose our enthusiasm for making any more contributions.

- ‘‘Resistant’’ Bottoms. We’ve just developed an exciting new initiative that could really make a difference to our workers and ultimately to the organization. For the workers, it means more involvement, more empowerment, more opportunity to make a difference. We bring it up to our workers, but there is no enthusiasm. To us, this is an exciting initiative, but to our workers living in this world of vulnerability, this is the latest installment of ‘‘them’’ doing it to ‘‘us’’ again. What have they got up their sleeves this time? What happened to last year’s exciting new initiative? Just wait it out; this too shall pass. We conclude that our workers are just too far gone for anything to excite them.

- ‘‘Weak’’ Middles. We’ve just made a simple request to our Middle; it’s about support we need from him on our project. That’s all we’re asking for. To us, it’s a simple request, but to our Middle struggling to survive in a tearing world, supporting us is working against someone else who is pressing Middle to support her. So instead of a strong commitment to support, we get a weak wishy-washy I’ll see what I can do. Where did we ever get such a weak Middle!

- ‘‘Nasty’’ Customers. We’re trying to be helpful to a disgruntled customer whose product has once again been delayed. There’s nothing we can do about product delivery, but we do want to soothe Customer’s ruffled feathers, so we invite Customer out for coffee; we also suggest a tour of the facility and present our customer survey form. Instead of gratitude, we get an angry reaction from Customer. To us, we are making reasonable gestures; to Customer living in the world of neglect, our nice gestures are simply more neglect! Some people are just unreachable by kindness!

- Burdened Tops. When we are Top, living in the context of complexity and accountability, we are vulnerable to reflexively sucking responsibility up to ourselves and away from others. It’s not a choice we make; it simply happens. We don’t see ourselves doing anything. It is just crystal clear to us that we are responsible for handling the complexity we are facing. The more regularly we do this, the more we increase our stress, the more we dilute the brain power that can be brought to bear on situations, the more we gradually disable others so that when we need them, they aren’t there for us.

- Oppressed Bottoms. When we are Bottom, living in the context of vulnerability, we are vulnerable to reflexively holding others responsible for our condition and the condition of the system. Again, we do this without awareness or choice. It’s crystal clear to us that they are responsible, not us. The more regularly we do this, the more righteous we become in our victimhood and the more bitter toward others; the less energy we devote to dealing with the very problems we are facing, and the less agency we feel in our lives. The system suffers from misdirected energy that is devoted to whining, complaining, resisting, and, possibly, sabotaging — energy that could have been focused more productively on the business of the system.

- Torn Middles.When we are Middle, living in the tearing context, we are vulnerable to sliding in between other people’s issues and conflicts and making them our own. It becomes crystal clear to us that we are responsible for resolving their issues. What makes this especially stressful is that they hold us responsible for resolving their issues. Sliding in between weakens us: we become confused, uncertain whose priorities to serve; we may not fully satisfy anyone, we get little positive feedback; and possibly we doubt our own competence. Middles cope with this tearing in different ways: some reduce the tearing by aligning themselves with Tops, others by aligning with Bottoms; in either case, they create tension with whomever they are not aligned. Other Middles cope with the tearing by bureaucratizing themselves, making it difficult for anyone to get to them. And still others burn themselves out shuttling back and forth, attempting to explain each side to the other, trying to placate all sides, struggling to please everyone. In all of these coping mechanisms is a loss of independence of thought and action. No independent Middle perspective is brought to bear, and as a consequence, the system loses whatever value such perspective could provide.Blindness to our own context results in personal stress, fractured relationships with others, and diminished organizational effectiveness.

- Screwed Customers. When we are Customer, living in the context of neglect, we are vulnerable to staying aloof from delivery systems and holding them responsible for delivery. It becomes crystal clear to us that they, not us, are responsible for delivery. So when delivery is unsatisfactory, we feel righteously angry at the supplier and personally blameless. Since it’s clear to us that we have no responsibility in the delivery process, whatever contribution we might have made to the quality of delivery is lost.

- In the Top context of complexity and accountability, instead of sucking responsibility up to myself and away from others, my challenge is to be a person who uses this context as an opportunity to create responsibility in others.

- In the Bottom context of things that are wrong with my condition and the condition of the system, instead of holding THEM responsible for all that is wrong, my challenge is to be a person who is responsible for my condition and the condition of the system.

- In the Middle context of tearing, instead of sliding in between and losing my independence of thought and action, my challenge is to maintain my independence of thought and action in the service of the system.

- In the Customer context of neglect, instead of standing aloof from the delivery process and holding it responsible for delivery, my challenge is to be a person who shares responsibility for delivery.

A PERSON IN THE BOTTOM CONTEXT

A PERSON IN THE MIDDLE CONTEXT

A PERSON IN THE CUSTOMER CONTEXT

To reiterate the basic point: regardless of what positions we and others occupy, we and they are constantly moving in and out of these contexts: sometimes as Top, sometimes as Bottom, sometimes as Middle, and sometimes as Customer.

Awareness of Persons in Context

We do not reflexively see context; we see people, and we tend to experience our interactions as person to person. Sometimes we are blind to the context others are living in, and sometimes we are blind to our own context. The basic point is that we are not just interacting people to people; we are people in context. Failure to recognize that can lead to serious misunderstandings, inappropriate actions, and dysfunctional consequences. In this section, I discuss the contextual principles at work on the personal level, provide some examples of what that context looks and feels like, and offer some strategies a leader can take in this situation to address the gap.

Principle 1: When We Are Blind to Others’ Contexts

Principle 1: When we are blind to others’ contexts, we are likely to fall into scenarios in which we misunderstand others’ actions, attribute inaccurate motives to them, respond in ways that negatively affect our relationships with them, and diminish our personal and organizational effectiveness:

Leadership strategy 1 comes into play in all of these situations:

Leadership strategy 1: Take others’ contexts into account. Make it possible, even easy, for them to do what it is you and your system need them to do.

There is no arrogant Top, resistant Bottom, weak Middle, or nasty Customer. What we have are people — just like us— struggling to cope with their respective contexts of complexity and accountability, vulnerability, tearing, and neglect. Our problem is that we have been reaching out and reacting as if these are just person-to-person interactions. In our context blindness, what we’ve done is increase the complexity of Top, the vulnerability of Bottom, the tearing of Middle, and the neglect of Customer, which is not what we had intended.

The challenge for us is to take context into account. This involves having an understanding of others’ context, having some empathy for them, not reacting to their initial responses, staying focused on what it is we are trying to accomplish, and being strategic, that is, rather than being blind to context, taking other people’s contexts into account. Given the context they are in, how do I make it possible for them to do what I need them to do? So, incorporated into my strategy are the following challenges: How do I reduce the complexity of Top, the vulnerability of Bottom, the tearing of Middle, and the neglect of Customer?

Principle 2: When We Are Blind to Our Own Contexts

Principle 2: When we are blind to our own contexts, we are vulnerable to falling into scenarios that are dysfunctional for us personally, for our relationships, and for our systems. We respond reflexively to these contexts — not all of us, not every time, but with great regularity — without awareness or choice. It is as if these scenarios happen to us without any agency on our part.

ABOUT THE POWER LAB AND THE ORGANIZATIONAL WORKSHOP

These immersion experiences for leaders are essential to the work of developing people-in-context ideas expressed in this article.

The Power Lab

The Power Lab, a total immersion experience, has been one of my main windows into systems. Devised to help leaders to deepen their knowledge, it has helped me deepen my own understanding of system phenomena.

A key feature of each Power Lab is The Society of New Hope, a three-class social system with sharp differences in wealth and power. Participants are randomly assigned to their class. The Elite (Tops) own or control all of the society’s resources — among them its bank, housing, food supply, court system, newspaper, and labor opportunities. At the other end are the Immigrants (Bottoms), who enter the society with little more than the clothes on their backs. Housing, meals, and supplies are available to them only if they sign up for work (mostly low-wage physical labor) that enables them to make purchases. And between the Elite and the Immigrants are the Managers (Middles), who enjoy middle-class amenities so long as they continue to manage the institutions of the Elite to the satisfaction of the Elite. This is a total immersion experience in that there are no breaks from the experience from the moment it begins to its end. This is not a role play; there are no instructions as to how people are to handle their situations. It is more like a life-within-life: These are the conditions into which you are born; deal with these conditions, and learn from them.

My role in many Power Labs was to function as an anthropologist — the name assigned to staff members whose job it was to capture the society’s history as it unfolded and, once the society ended, to report on that history in ways that enabled participants to see the entirety of the experience, not just the part they played. Anthropologists get the rare opportunity to see whole systems. By agreement with participants, I had access to all deliberations within and across class lines. This view from the outside allowed me to observe the regularly recurring patterns described in this article: the territoriality that developed at the top, the fractionation in the middle, the conforming cohesiveness at the bottom. This view from the outside also enabled me to see and describe the different contexts out of which these patterns emerged: the complexity at the top, the tearing in the middle, and the shared vulnerability at the bottom.

When each societal experience ended, participants shared in an intensive debriefing session what I could not see from my outside perspective: their experiences, thoughts, and feelings as they struggled to deal with their contexts. It was out of these conversations that I began to grasp the uniquely different forms of consciousness that developed in each context: the ‘‘mine’’ mentality at the top, the ‘‘I’’ in the middle, and the ‘‘we’’ at the bottom.

The Organization Workshop

The Organization Workshop experience has two functions: to educate participants about organizational life and to continue my education in systems. Unlike Power Lab, which lasts for several days, the Organization Workshop lasts only a few hours. An organization is created composed of groups of Tops, Middles, and Bottoms; outside the organization are customers and potential customers with projects for the organization to work on and funds to pay for service. Participants are randomly assigned to positions; there are no instructions on how to play one’s position. The conditions are created, and participants adapt as best as they can.

While developing the Organization Workshop, I had a significant insight. For a long time, I felt responsible for helping people understand what happened over the life of the organization. (I was feeling very Top and sucking all responsibility up to myself!) I would take my yellow pad in hand and run from place to place trying to observe and make sense of events. But the action was fast-moving, and there was no way I could capture the story in this setting. Then came the insight: ‘‘TOOT’’ (Time Out Of Time). During TOOT, organization action stops and members in each part of the system describe what life is like for them in their context: the issues they are dealing with, the feelings they are experiencing, the nature of their peer group relationships. TOOT has a powerful simplicity. It requires only that participants listen so that they might understand the contexts in which others are living and then consider the implications that knowing has for how they feel toward each other and how they choose to interact (Oshry, 2007).

In all of these scenarios, blindness to our own context results in personal stress, fractured relationships with others, and diminished organizational effectiveness. The solution is to turn to leadership strategy 2:

Leadership strategy 2: Recognize the context you are in, move past the reflexive disempowering response, and use the possibility of whatever context you are in to strengthen yourself, your relationships with others, and the system.

To master our own context, we need to understand that in system life, we are constantly moving in and out of Top, Middle, Bottom, and Customer contexts. We need to be able to recognize whatever context we are in at the moment. Am I Top, Middle, Bottom, or Customer in this moment? We need to be able to notice our reflex response in whatever context we are in. Am I sucking up responsibility to myself and away from others? Am I holding THEM responsible for my condition and the condition of the system? Am I sliding in between other people’s issues and conflicts and making them my own? Am I staying aloof and holding the delivery system responsible for delivery?

Sometimes the clue to context lies in our feelings: I’m feeling burdened or oppressed or torn or screwed. What is that feeling telling me about the context I am in, and how I am responding to it? Am I feeling burdened because I’m sucking responsibility up to myself? Am I feeling oppressed because I’m holding others responsible? Am I feeling torn because I’m sliding in between others’ issues? Am I feeling screwed because I’m holding the delivery system responsible for delivery?

Awareness allows us to avoid the negative consequences of blindness. Beyond that, it opens up more powerful and productive possibilities for responding to context, possibilities that strengthen ourselves and our systems— for example:

We are much more powerful and more contributing system members when, in the Top context, we are creators of responsibility in others; when, in the Bottom context, we are responsible for our condition and the condition of the system; when, in the Middle context, we maintain our independence of thought and action; and when, in the Customer context, we share responsibility for the delivery of products and services. Living from these transformative stands demands that we use more of our potential in whatever context we are in, and it enables us to focus more of our creative energies on the business of the system. These stands also raise unique challenges for us. As Tops, we need to give up some control; as Bottoms, we need to give up our dependency and blame; as Middles, we need to give up our need to please everyone; and as Customers, we need to give up our sense of entitlement.

These are the payoffs and the prices to be paid for seeing, understanding, and mastering the systemic contexts in which we are living. In this section, we explored the leadership challenges of seeing, understanding, and mastering individuals in context. Now we turn our attention to groups in context.