A Massachusetts teacher I once knew asked his tenth graders to blurt out the first words that came to mind on hearing the word “power.” They said, “money,”, “parents,”, “guns,” “bullies,”, “Adolf Hitler,” and “Mike Tyson.” And in my workshops with adults, I’ve heard similar words, plus “fist,”, “law,”, “corrupt,” and “politicians.” Often “men” pops out, too.

TEAM TIP

While the author focuses on power in a societal sense, discuss how the principles she outlines might apply in an organizational setting.

As long as we conceive of power as the capacity to exert one’s will over another, it is something to be wary of. Power can manipulate, coerce, and destroy. And as long as we are convinced we have none, power will always look negative. Even esteemed journalist Bill Moyers recently reinforced a view of power as categorically negative., “The further you get from power,” he said, “the closer you get to the truth.”

But power means simply our capacity to act., “Power is necessary to produce the changes I want in my community,” Margaret Moore of Allied Communities of Tarrant (ACT) in Fort Worth, Texas, told me. I’ve found many Americans returning power to its original meaning — “to be able.” From this lens, we each have power — and often, much more power than we think.

One Choice We Don’t Have

In fact, we have no choice about whether to be world changers. If we accept ecology’s insights that we exist in densely woven networks then we must also accept that every choice we make sends out ripples, even if we’re not consciously choosing. So the choice we have is not whether, but only how, we change the world. All this means that public life is not simply what officials and other “big shots” have.

So the choice we have is not whether, but only how, we change the world.

One related evidence of our power is so obvious it is often overlooked. Human beings show up in radically different notches on the “ethical scale” depending on the culture in which we live. In Japan, “only” 15 percent of men beat their spouses. In many other countries, over half do. The murder rate in the United States is four times higher than in Western Europe, Canada, Australia, and Japan.

Plus, behavior can change quickly. Germany moved from a country in which millions of its citizens went along with mass murder to become in a single generation one of the world’s more respected nations. An incomparably less consequential but still telling example: In only a decade, 1992 to 2002, U. S. high school students who admitted to cheating on a test at least once in a year climbed by 21 percent to three-quarters of all surveyed.

So what do these differences and the speed of change in behavior tell us? That it is culture, not fixed aspects of human nature, which largely determines the prevalence of cooperation or brutality, honesty or deceit. And since we create culture through our daily choices, then we do, each of us, wield enormous power.

Let me explore related, empowering findings of science that also confirm our power.

Mirrors in Our Brains

Recent neuroscience reveals our interdependence to be vastly greater than we’d ever imagined. In the early 1990s, neuroscientists were studying the brain activity of monkeys, particularly in the part of the brain’s frontal lobe associated with distinct actions, such as reaching or eating.

They saw specific neurons firing for specific activities. But then they noticed something they didn’t expect at all: The very same neurons fired when a monkey was simply watching another monkey perform the action.

“Monkey see, monkey do” suddenly took on a whole new meaning for me. Since we humans are wired like our close relatives, when we observe someone else, our own brains are simultaneously experiencing at least something of what that person is experiencing. More recent work studying humans has borne out this truth.

These copycats are called “mirror neurons,” and their implications are staggering. We do walk in one another’s shoes, whether we want to or not.

“[Our] intimate brain-to-brain link-up . . . lets us affect the brain — and so the body — of everyone we interact with, just as they do us.” — Daniel Goleman, Social Intelligence: The New Science of Human Relationships

We literally experience and therefore co-create one another, moment to moment. For me, our “imprintability” is itself a source of hope. We can be certain that our actions, and perhaps our mental states, register in others. We change anyone observing us. That’s power.

And we never know who’s watching. Just think: It may be when we feel most marginalized and unheard, but still act with resolve, that someone is listening or watching and their life is forever changed.

As I form this thought, the face of Wangari Maathai comes to mind. A Kenyan, Wangari planted seven trees on Earth Day in Nairobi in 1977 to honor seven women environmental leaders there. Then, over two decades, she was jailed, humiliated, and beaten for her environmental activism, but her simple act ultimately sparked a movement in which those seven trees became forty million, all planted by village women across Kenya.

In the fall of 2004, when Maathai got the call telling her she had just won the Nobel Peace Prize, her first words were:, “I didn’t know anyone was listening.” But clearly, a lot of people were beginning to listen, from tens of thousands of self-taught tree planters in Kenya to the Nobel committee sitting in Oslo.

From there I flash back to a conversation with João Pedro Stédile, a founder of the largest and perhaps most effective social movement in this hemisphere — Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement, enabling some of world’s poorest people to gain nearly twenty million acres of unused land. Under Brazil’s military regime in the early 1980s even gathering a handful of people was risky. And, in that dangerous time, who helped motivate João Pedro? It was César Chávez, he told me, and the U. S. farm workers.

I’ll bet Chávez never knew.

Just as important, the findings of neuroscience also give us insight as to how to change and empower ourselves. They suggest that a great way is to place ourselves in the company of those we want most to be like. For sure, we’ll become more like them. Thus, whom we choose as friends, as partners, whom we spend time with — these may be our most important choices. And “spending time” means more than face-to-face contact. What we witness on TV, in films, and on the Internet, what we read and therefore imagine — all are firing mirror neurons in our brains and forming us.

As the author of Diet for a Small Planet, I’m associated with a focus on the power of what we put into our mouths. But what we let into our minds equally determines who we become. So why not choose an empowering news diet? I’ve included my own menu suggestions in Recommended Reading at the end of Getting a Grip: Clarity, Creativity, and Courage in a World Gone Mad (Small Planet Media, 2007).

Power Isn’t a Four-Letter Word

Power is an idea. And in our culture it’s a stifling idea. We’re taught to see power as something fixed — we either have it, or we don’t. But if power is our capacity to get things done, then even a moment’s reflection tells us we can’t create much alone.

From there, power becomes something we human beings develop together — relational power. And it’s a lot more fun.

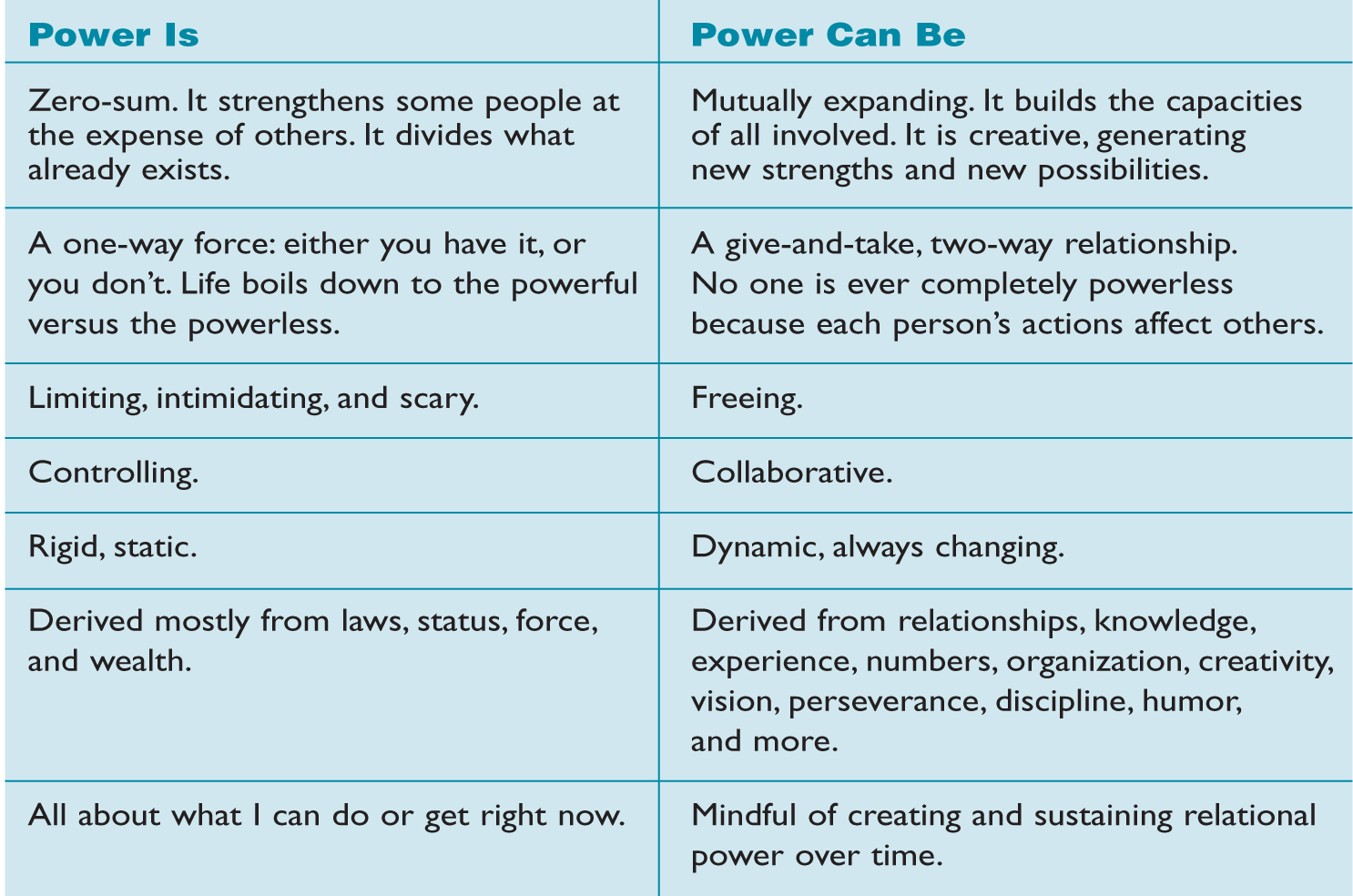

“Relational” suggests that power can expand for many people simultaneously. It’s no longer a harsh, zero sum concept — the more for you, the less for me. The growth in one person’s power can enhance the power of others. Idea 3 (see table) contrasts our limited, negative view of power with a freeing, relational view.

Let me tell you one story of relational power.

In the 1970s, pollution in Chattanooga, Tennessee, was so bad that drivers had to turn on headlights at noon to cut through it. But in the 1990s, this once-charming city — famous for its choo-choos — went from racially-divided ugly duckling to swan, winning international awards and the envy of its neighbors.

The city’s rebirth sprang in part from big investments in the city’s cultural renewal — including the world’s largest freshwater aquarium, attracting over a million visitors a year; a renovated theater involving one thousand volunteers annually; and a new riverfront park.

But all these weren’t the city fathers’ ideas.

IDEA 3: RETHINKING POWER

Twenty years ago, fifty spunky, frustrated citizens declared that the old ways of making decisions weren’t working and drew their fellow residents — across race and class lines — into a twenty-week series of brainstorming sessions they called “visioning.” Their goal was hardly modest — to save their city by the end of the century. They called itVision 2000. They drew up thirty-four goals, formed action groups, sought funding, and rolled up their sleeves.

By 1992, halfway along, the Visioners had already achieved a remarkable 85 percent of their goals. Smog was defeated, tourism was booming thanks to the new aquarium, crime was down, and jobs and lowincome housing were on the rise. People stayed downtown after dark, and the refurbished riverside had become an oak-dappled mecca.

Chattanoogans didn’t stop there. In 1992, a citywide meeting to shape a school reform agenda drew not the small crowd expected but fifteen hundred people, who generated two thousand suggestions.

By now the approach has seeped its way into the city’s culture. In 2002, to plan a big waterfront project, three hundred people participated in a “charrette” where teams used rolls of butcher paper to draw what they wanted to see happen.

“Basically, everything we do, any major initiative in Chattanooga, now involves public participation,” said Karen Hundt, who works for a joint city-county planning agency. From Atlanta to West Springfield, Massachusetts, from Bahrain to Zimbabwe, citizens taken by Chattanooga’s story are rewriting it to suit their own needs.

Here power is not a fixed pie to be sliced up. It grows as citizens join together, weaving relationships essential to sustained change.

Relational Power’s Under Appreciated Sources

While we commonly think of power in the form of official status or wealth or force restricted to a few of us, take a moment to mull over these twelve sources of relational power available to any one of us:

- Building Relationships of Trust. Thirty-five hundred congregations — Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and some Evangelicals and Muslims — are dues-paying members of one hundred thirty-three religious networks nationwide. These local federations with members adding up to as many as three million Americans are successfully tackling problems that range from poverty wages to failing schools. Their genius is what they call “one-on-one” organizing strategies. These involve face-to-face meetings allowing ordinary people to discover their own capacities because someone — finally — is listening.

- Ability to Analyze Power and Self-Interest. One such organization, Communities Organized for Public Service in San Antonio, analyzes corporate interests before bringing corporations into dialogue on job-training reform.

- Knowledge. National People’s Action documents banks’ racial “redlining” in lending and helps to pass the federal Community Reinvestment Act, which has brought over a trillion dollars into poor neighborhoods. Workers at South Mountain Company in Massachusetts buy the company and apply knowledge from their direct experience to make it profitable and to incorporate energy efficient methods.

- Numbers of People. The congregation-based Industrial Areas Foundation is able to gather together thousands for public “actions,” commanding the attention of lawmakers.

- Discipline. Young people in the Youth Action Program — precursor to the nationwide Youth Build — handle themselves with such decorum at a New York’s City Council meeting that officials are moved to respond to the group’s request for support.

- Vision. In the Merrimack Valley Project in Massachusetts, some businesses “catch” the citizens’ vision of industry responsive to community values and change their positions.

- Diversity. Memphis’s Shelby County Interfaith organization identifies distinct black and white interests on school reform and multiplies its impact by addressing both sets in improving Memphis schools.

- Creativity. Citizens in St. Paul devise their own neighborhood network to help the elderly stay out of nursing homes. Regular folks in San Antonio devise a new job training program that’s become a national model.

- Persistence. Members of ACORN, a two hundred twenty-five thousand member-strong, low-income people’s organization, stand in line all night to squeeze out paid banking lobbyists for seats in the congressional hearing room debating the Community Reinvestment Act.

- Humor. Kentuckians for the Commonwealth stage a skit at the state capitol. In bed are KFTC members portraying legislators and their farmer chairperson pretending to be a coal lobbyist. They pass big wads of fake cash under the covers. Grabbing media attention, they get their reform measure passed.

- Chutzpah — Nerve. Sixth graders in Amesville, Ohio, don’t trust the EPA to clean up after a toxic spill in the local creek, so they form themselves into the town’s water quality control team and get the job done.

- Mastering the Arts of Democracy. Organizations of the Industrial Area Foundation network, over fifty nationwide, evaluate and reflect — often right on the spot — following each public action or meeting. They ask: How do you feel? How did each spokesperson do? Did we meet our goals? A seasoned organizer will also try to teach a lesson about what the organization sees as the “universals” of public life, such as relational power.

Drops Count

Sadly, though, many of us remain blind to such a promising reframing of possibility. Imagining ourselves powerless, we disparage our acts as mere drops in the bucket … as, well, useless. But think about it: Buckets fill up really fast on a rainy night. Feelings of powerlessness come not from seeing oneself as a drop; they arise when we can’t perceive the bucket at all. Thus, to uproot feelings of powerlessness, we can work to define and shape the bucket — to consciously construct a frame that gives meaning to our actions (see “Spirals of Powerlessness and Empowerment” on p. 5).

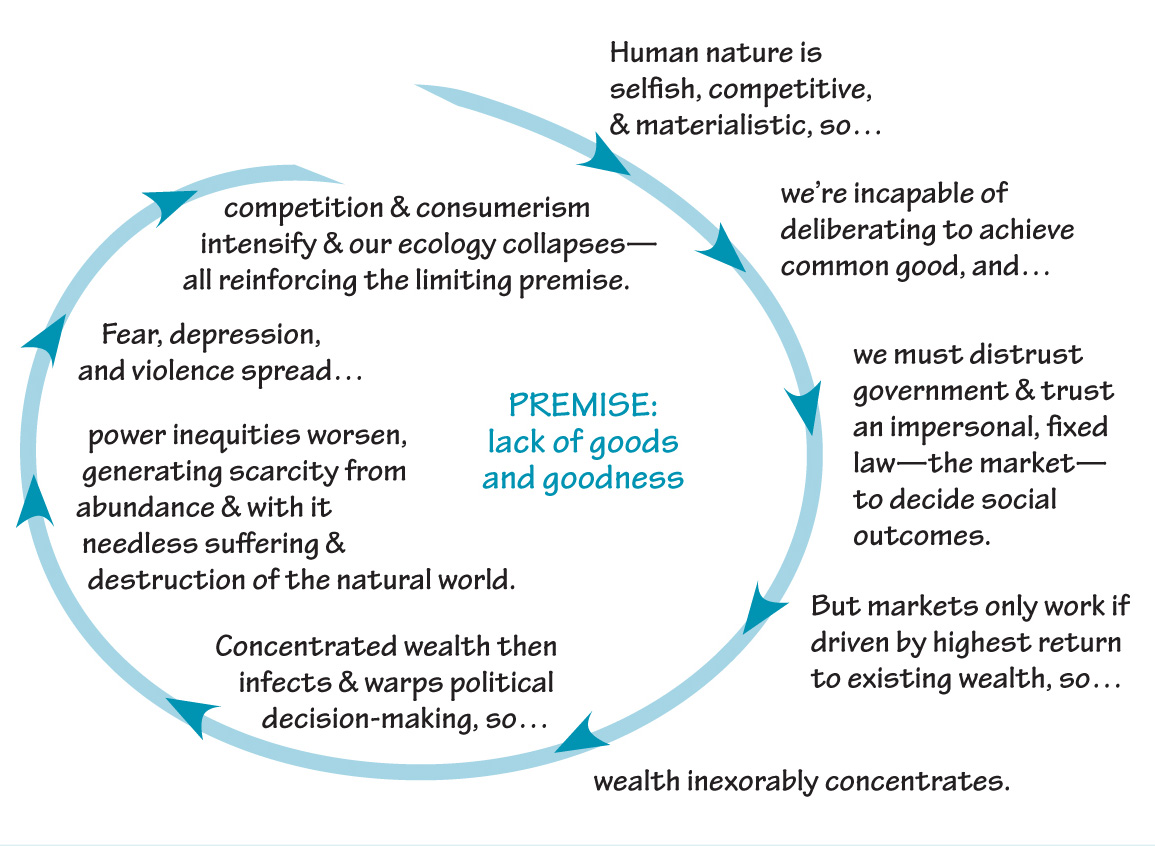

SPIRALS OF POWERLESSNESS AND EMPOWERMENT

The Spiral of Powerlessness and the Premise of Lack

The “Spiral of Powerlessness” is the scary current of limiting beliefs and consequences in which I sense we’re trapped. Its premise is “lack.” There isn’t enough of anything, neither enough “goods” — whether jobs or jungles — nor enough “goodness” because human beings are, well, pretty bad. These ideas have been drilled into us for centuries, as world religions have dwelt on human frailty, and Western political ideologies have picked up similar themes.

“Homo homini lupus [we are to one another as wolves],” wrote the influential seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes. Repeating a Roman aphorism — long before we’d learned how social wolves really are — Hobbes reduced us to cutthroat animals.

“Private interest . . . is the only immutable point in the human heart.”

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1835

From that narrow premise, it follows that it’s best to mistrust deliberative problem-solving, distrust even democratic government, and grasp for an infallible law — the market! — driven by the only thing we can really count on, human selfishness. From there, wealth concentrates and suffering increases, confirming the dreary premises that set the spiral in motion in the first place.

What this downward spiral tells me is that we humans now suffer from what linguists call “hypocognition,” the lack of a critical concept we need to thrive. And it’s no trivial gap! Swept into the vortex of this destructive spiral, we’re missing an understanding of democracy vital and compelling enough to create the world we want.

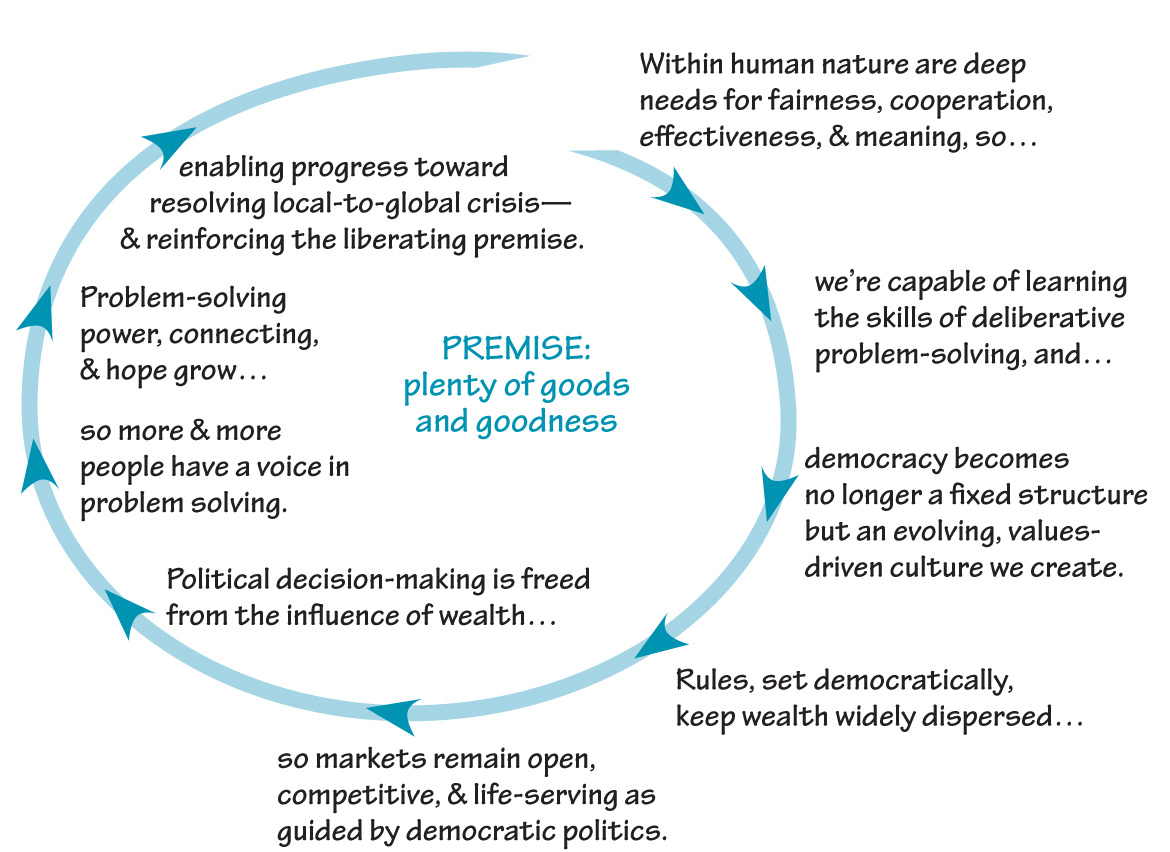

The Spiral of Empowerment and the Premise of Plenty

In contrast to the premise of lack in the opening “Spiral of Powerlessness,” these five qualities generate a spiral of human growth and satisfaction I’ve striven to capture in the “Spiral of Empowerment.” Its premise is plenty — that as we come to appreciate and enjoy nature’s laws, learning to live within a self-renewing ecological home, we discover there’s more than enough for all to live well.

This realization I first experienced as a lightning bolt, when in my twenties I learned that there was more than enough food in the world to make us all chubby . . . and there still is, even considering staggering built-in waste. I learned that we create the scarcity we fear. Worldwide, for example, more than a third of all grain and 90 percent of soy gets fed to livestock.

I learned that this irrationality took off, even though inefficient and harmful to health, because one-rule economics leaves millions of people too poor to buy food and keeps grain so cheap that it’s profitable to feed vast amounts to animals.

Beyond food, the U. S. economy remains “astoundingly” wasteful, conclude the authors of Natural Capitalism, as “only 6 percent of its vast flows of materials actually end up in products.” Imagine, then, the potential plenty, not to mention health benefits, as we shift toward equity and efficiency.

Similar plenty appears once we drop the scarcity lens surrounding energy. Our sun, wind, waves, water, and biomass offer us a “daily dose of energy” 15,000 times greater than in all the planet-harming fossil and nuclear power we now use, says German energy expert Hermann Scheer. Just one-fifth of the energy in wind alone would, if converted to electricity, meet the whole world’s energy demands, reports a Stanford NASA study.

An awareness of plenty itself undermines a focus on raw, self-centered competition, leaving us able to refocus not on the goodness of human nature, which seems to deny human complexity, but on the undeniable goodness in human nature, including the deep positive needs and capacities just mentioned.

From there, the “Spiral of Empowerment” quickens. We gain confidence that we can learn to make sound decisions together about the rules that further healthy communities. Then, as we begin to succeed and ease the horrific oppression and conflict that now rob us of life, we reinforce positive expectations about our species. The destructive mental map loosens its hold. And as these capacities and needs — for fairness, connection, efficacy, and meaning — find avenues for expression, they redound, generating even more creative decision making and outcomes.

So “getting a grip” doesn’t have to mean a sober struggle. From this more complete view of our own nature and of what nature offers, could it instead become an exhilarating adventure?

The Spiral of Empowerment and the Premise of Plenty

powerment” on p. 5). That satisfying exploration begins, I believe, when we recognize that our planet’s multiple crises are neither separate nor random. They flow largely from a partial, and thus distorted, view of our own nature, which leads us to turn our fate over to forces outside our control, especially to a one-rule economy violating deep human sensibilities, not to mention our common sense. Our deepening crises flow, as well, from humanity’s to-date lack of preparedness to identify and skillfully to confront the tiny minority among us who seem to lack empathetic sensibilities.

As you now know, for me a “bucket” that both contains and gives meaning to our creative, positive acts is Living Democracy. It springs from and meets humanity’s common and deep emotional and spiritual needs. So, I wonder: In a world torn apart by sectarian division, could Living Democracy become a uniting civic vision complementing our religious and spiritual convictions — a nonsectarian yet soul-satisfying pathway out of the current morass?

I can’t be certain, of course, but I think so.

And then again, I ask myself often, whatever the real odds of reversing our global catastrophe, is there a more invigorating way to live than that of making democracy a way of life?

In answering that question negatively, I am certain.

Frances Moore Lappé is the author of 16 books, beginning with the 1971 three-million-copy bestseller, Diet for a Small Planet, which awakened a whole generation to the human-made causes of hunger and the significance of our everyday choices. This article is reprinted with permission from Chapter 4 of her newest book, Getting a Grip: Clarity, Creativity, and Courage in a World Gone Mad (Small Planet Press, 2007). For more information, go to www.gettingagrip.net. For chapter source notes, go to “The Book—End Notes.”