Apparently, size does matter these A days—particularly in the American biotech industry. According to Hambrecht and Quist, an investment bank, large biotechnology companies (those with market capitalizations of $1 billion or more) have enjoyed a 7percent jump in shares since early 1999. At the same time, relatively small firms (those worth less than $200 million) have dropped in value by 12 percent.

As The Economist observes, “Rich biotechnology firms seem to be getting richer mainly because they offer results that investors can understand: products on the market, and profits right now. Many such companies had their start in the 1980s . . . when all it took to catch an [investor’s] eye was a bright idea and a lot of energy.”

This situation bears a resemblance to other strange phenomena in life— when something (a company, an individual, a product) gets a lucky head start and just keeps getting bigger, richer, or more successful. One “lens” through which to view this situation is the “Success to the Successful” systems archetype. In a “Success to the Successful” situation, if one party (A) is given more resources through some random event, it has a higher likelihood of succeeding than another party (B). This initial success justifies devoting more resources to A than B. As B gets fewer resources, its success diminishes, further justifying even more resource allocations to A.

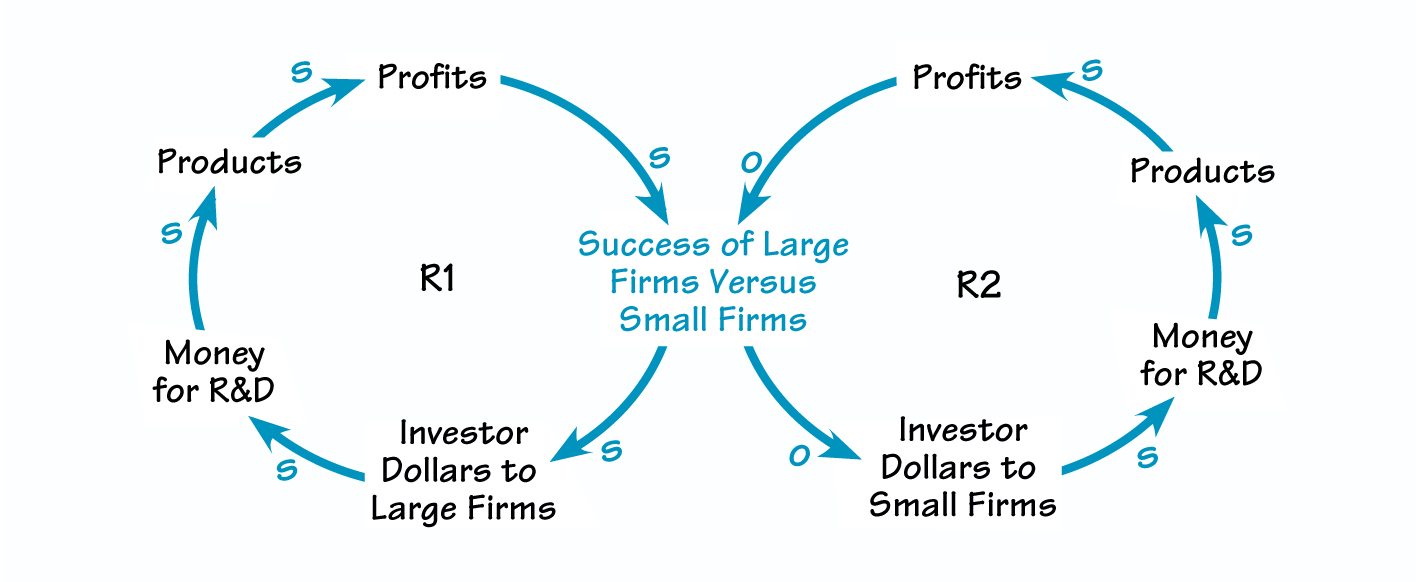

In the biotech industry, the attention and funding that certain firms attracted during the halcyon days of the industry’s emergence gave these firms a “jump start” that has sustained their growth ever since (see R1 in “Success to the Big Firms”). Companies that missed out on these early opportunities failed to attract investor dollars. They never managed to achieve high-profile status in the industry—a fate that has only strengthened investors’ loyalty to the originally successful firms (R2).

SUCCESS TO THE BIG FIRMS

Early successes for certain biotech firms attracted lots of investor dollars, which furthered these firms’ success and attracted additional capitalization. Those initial successes set up a systemic structure by which other firms that didn’t get lucky during the industry’s emergence never “got off the ground.”

Stopping the Spiral?

It’s easy to blame investors for contributing to the situation through their individual decisions. But on the other hand, they’ve got valid reasons for staying loyal to the bigger companies. Made impatient by their bountiful earnings during the industry’s early days, investors now have little interest in waiting out the “slow-but-steady progress that goes into building a biotechnology company. . . .” Biotechnology is also a risky field, with very few products surviving clinical trials and making it onto the market. This uncertainty just reinforces investors’ desire to play it safe by sticking to the large, proven companies.

So, given the power of this systemic structure, what’s a smaller biotech firm to do? As The Economist opines, such companies should consider merging, so as to amass the heft they’ll need to do battle with the big guns. They might also gain an edge by forging R&D partnerships with pharmaceutical firms or larger biotech companies. Finally, venture-capital financing seems to be alive and well; if they can manage to attract these dollars, smaller biotech firms may have a chance to regain some momentum—and turn this stubborn spiral around.

Lauren Keller Johnson is publications editor at Pegasus Communications