What makes a great collaboration? One view is that a collaboration is only as great as the individuals who collaborate within it. Another is that a collaboration is also only as great as the vision that drives it. My belief is that the shared vision is primary. A vision is something you reach for, something you aspire to, something that is the glue of your enterprise, the driving force, the vitality within it. In our world today, the thing we are most lacking is vision.

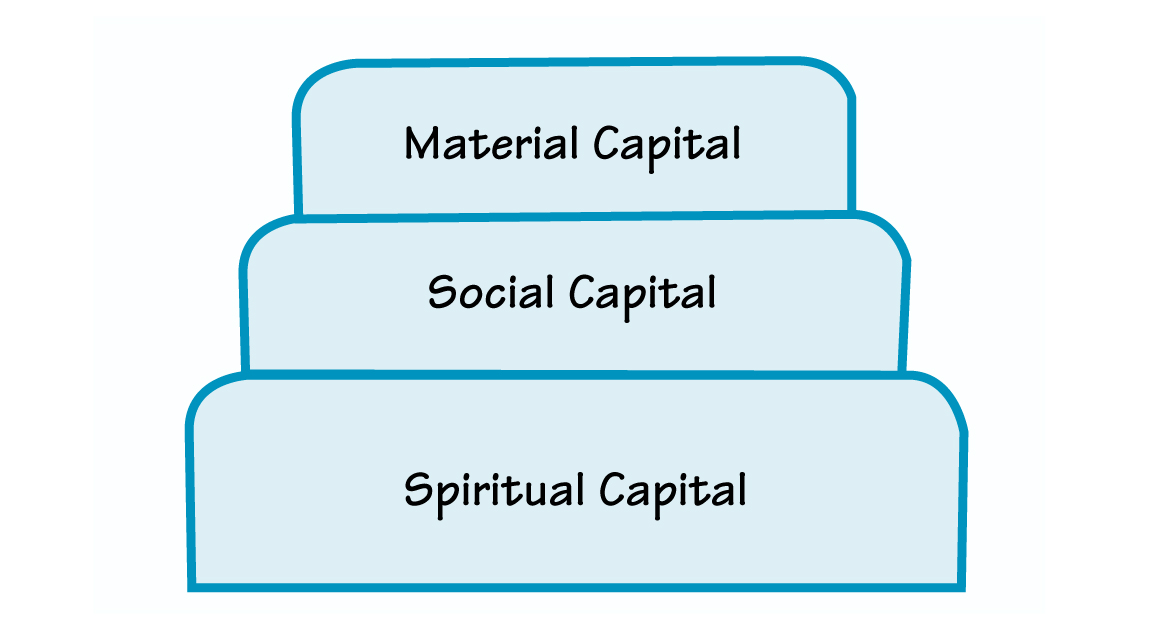

Part of the reason many of our collaborations lack vision is because they’re based on only one kind of capital — material. It’s true that any kind of enterprise we want to engage in requires some kind of financial wealth if it wants to succeed in the short term. But for a collaboration to sustain itself over the long term, it needs two other forms of wealth: social and spiritual. These three types of capital are connected similarly to a wedding cake. Material capital sits on the top layer, social capital lies in the middle, and spiritual capital rests on the bottom, supporting all three (see “Three Forms of Capital”).

According to political economist Francis Fukuyama, who wrote Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity (Free Press, 1995), social capital can be measured by the amount of trust in a society, empathy people feel for each other, and commitment to the health of the community. The health of a community, he says, can be measured by criteria such as the rate of crime, divorce, literacy, and litigation.

THREE FORMS OF CAPITAL

Most collaborations are based only on material capital. But in order for the partnership to thrive, people must also pay attention to two other forms of wealth: social and spiritual capital.

A New Paradigm of Intelligence

Even more fundamental than social capital, spiritual capital reflects what an individual or organization exists for, believes in, aspires to, and takes responsibility for. Based on this definition, it is a new paradigm that requires us to radically change our mindset about the philosophical foundations and practices of business, or any enterprise for that matter. I am not referring here to religion or spiritual practices. Rather, I mean the power an individual or organization can manifest based on their deepest meanings, values, and purposes.

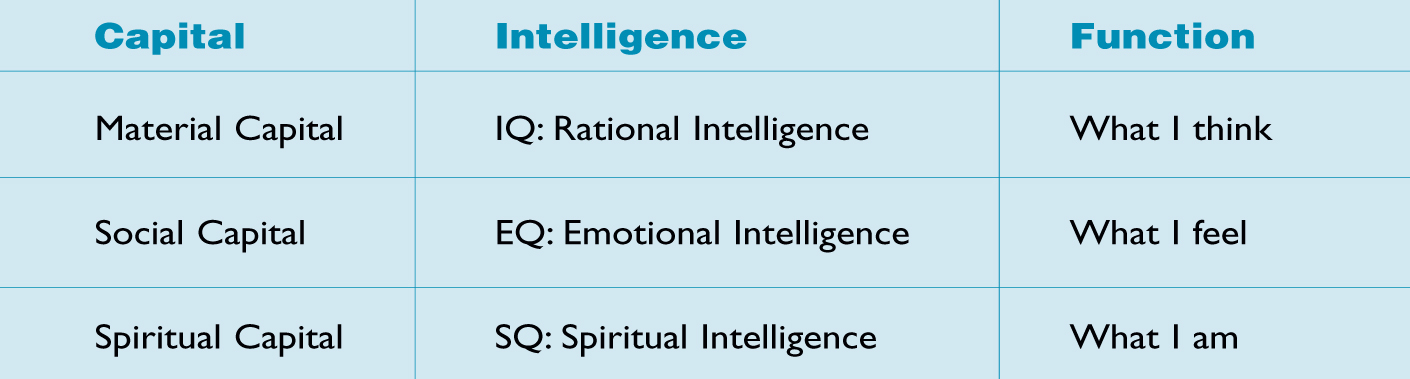

We build all three forms of capital by using our intelligence. And I’m not just talking about IQ. I’m referring also to the collective intelligence of the heart, the mind, and the spirit. I have written a great deal about the types of intelligence that correlate to the three types of capital (see “Three Types of Intelligence”).

THREE TYPES OF INTELLIGENCE

IQ, or intelligence quotient, was discovered in the early 20th century and is tested using the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales. It refers to our rational, logical, rule-bound problem solving intelligence. It is supposed to be what makes us bright or dim. It is also a style of thinking. All of us use some IQ, or we wouldn’t be functional.

EQ refers to our emotional quotient. In the mid-1980s, in his book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ (Bantam, 1995), Daniel Goleman articulated the kind of intelligence that our heart, or emotions, have. EQ is manifested in trust, empathy, emotional self-awareness and self-control, and the ability to respond appropriately to the emotions of others. It’s a sense of where people are coming from; for example, if someone looks like they’ve had a row with their wife before coming into the office that morning, it’s not the best time to ask them for a pay raise or put a new idea across.

SQ, or spiritual intelligence, underpins IQ and EQ. Spiritual intelligence is an ability to access higher meanings, values, abiding purposes, and unconscious aspects of the self and to embed these meanings, values, and purposes in living richer and more creative lives. Signs of high SQ include an ability to think out of the box, humility, and an access to energies that come from something beyond the ego, beyond just me and my day-to-day concerns.

All of us at some point do get in touch with that higher self. Researchers say that 70 percent of adults throughout the world, regardless of culture, education, or background, have had what they call “peak experiences.” Peak experiences are those moments when you suddenly feel that everything is beautiful, that there’s a tremendous oneness to being, or that love suffuses the world. You really feel them with your whole being, and then they flash by and are gone. Often people are shaken by having these experiences and don’t talk about them. But at least 70 percent of the world’s adult population is in touch with energy and meaning coming from a higher or deeper sphere.

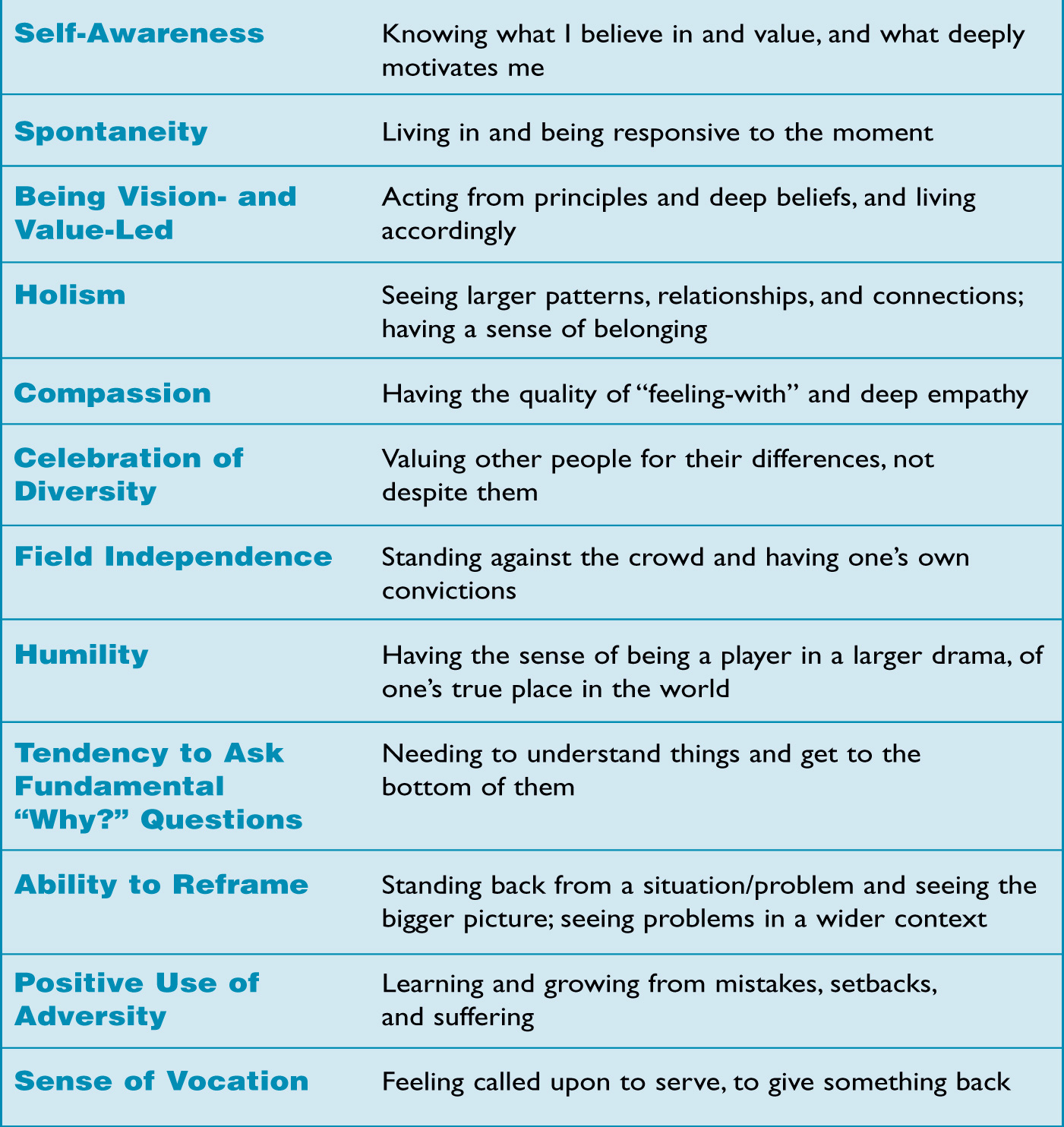

12 PRINCIPLES OF SPIRITUAL INTELLIGENCE

12 Principles of Spiritual Intelligence

I believe that all human beings are born with the capacity to use these three intelligences to some measure because each supports our survival. Some of us may be strong in one and weak in others, but each can be nurtured and developed. Spiritual intelligence can be fostered by applying 12 principles (see “12 Principles of Spiritual Intelligence”).

Ian Marshall and I derive these principles from qualities that define complex adaptive systems. In biology, complex adaptive systems are living systems that create order out of chaos. They are highly unstable, poised at the edge of chaos, which is what makes them so sensitive. These systems are holistic, emergent, and respond creatively to mutations. They’re in constant creative dialogue with the environment.

Each one of us is a conscious complex adaptive system, both physically and mentally. Any great collaboration we hope to build will have flexible boundaries and be in constant dialogue with itself and its environment. As I describe the qualities of the 12 principles, know that I am also listing the qualities that I think would define a great collaboration, underpinned by vision, purpose, meaning, and values.

Self-Awareness. This principle is different from Goleman’s emotional self-awareness, which refers to knowing what we’re feeling at any given moment. Spiritual self-awareness means to recognize what I care about, what I live for, and what I would die for. It’s to live true to myself while respecting others. Being authentic in this way is the bedrock of genuine communication with our deeper self that allows us to bring that self into the outer world of action.

Spontaneity. Being spontaneous does not mean merely acting on a whim but refers to behavior honed by the self-discipline, practice, and self-control of the martial arts warrior. To be spontaneous means letting go of all your baggage — your childhood problems, prejudices, assumptions, values, and projections — and be responsive to the moment. And since spontaneity comes from the same Latin root as responsibility, it means taking responsibility for our actions in the moment.

Being Vision and Value-Led. Vision is the capacity to see something that inspires us and means something broader than a company vision or a vision for educational development. It seeks answers to the bigger, more difficult questions such as Why do we want the world to have our products? and What are we trying to educate children for?

When my son was five, he knocked me backwards with the question, “Mommy, why do I have a life?” It took me months to think of an appropriate answer. He was probably expecting me to say, “So you can be rich or so you can be a good doctor.” Instead, I finally told him, “You have a life so you can leave the world a better place than you found it. You have a life so that you can make a difference.” I don’t know what he made of that at five, but he’s at university now, and we recently had the same conversation. “Mom, shall I go to university? What shall I study? I feel a bit lost.” And again I said to him, “Follow your heart. Don’t think what Mom and Dad want you to do. Follow what you want to do. But whatever you do, make a difference with it.” That’s having a life that’s led by vision and values.

Holism. In quantum physics, holism refers to systems that are so integrated that each part is defined by every other part of the system. As I stand here in this room, which is a system, the words that I say, the tone of my voice is partly brought out by speaking to you. And you are partly responding to me. For the moment that we are together this morning, we are defined in terms of each other. What I think, feel, and value affects the whole world. Holism encourages cooperation, because as you realize you’re all part of the same system, you take responsibility for your part in it. A lack of holism encourages competition, which encourages separateness. For more effective collaborations, we need cooperation and a sense of oneness.

When someone disagrees with me, he or she literally makes me grow new neurons.

Compassion. In Latin compassion is defined as “feeling with.” I don’t just recognize or accept your feelings, I feel them. This is particularly hard to do with someone who has hurt you. Can you feel the pain and frustration behind their behavior? You don’t have to let them treat you that way, and often you do have to fight. But fight with compassion, with understanding, with knowledge of your enemy.

Celebration of Diversity. Compassion is strongly linked to the principle of diversity. Many organizations offer diversity programs that involve, for example, putting a token woman on the board of directors or ensuring that a certain percentage of ethnic groups is represented in the workforce. But I mean something different. We celebrate our differences because they teach us what matters.

Growing up, I was part of a large extended family that got together every Thanksgiving and Christmas. We were a mixture of Republicans and Democrats, Catholics and Protestants, and a few Jews, and everyone had very strong opinions that they liked to express. So my mother made a rule at these dinners that we could talk about anything but politics and religion. Every single holiday, by the time we tucked into the turkey, everybody broke the rules. All hell would break loose as people shouted and called each other names. My Aunt Vera always left the table weeping, and my mother always trembled. I thrived on it. This was my kindergarten of debate and dialogue. It taught me that this type of expression is where the energy is in a group. The passion of the family, our ability to learn from each other, was in our differences.

When someone disagrees with me, he or she literally makes me grow new neurons. I have to rewire my brain, challenge my assumptions, and question my values. I learn. When a group experiences divisive, painful issues, some people ask, Dare we confront them? Mightn’t they split us? Shouldn’t we put aside our differences and see what we can agree about? Absolutely not. Celebrate the differences. Cauterize the pain by letting it come out. That’s where the passion and energy is in our collaborations. You’ll find that, if you do it in a dialogic spirit, the collaboration becomes a container that can hold all that diversity and allow it to emerge into something new. By not bringing it into the group, you lose that energy. Celebrating diversity means that I appreciate that you rattle my cage, because by doing so, you make me think and grow.

Field Independence. Field independence is a term from psychology that means “to stand against the crowd,” to be willing to be unpopular for what I believe in. It’s a willingness to go it alone, but only after I’ve carefully considered what others have to say.

Humility. Humility is the necessary other side of field independence, whereby I realize that I am one actor in a larger play and that I might be wrong. So I question myself ruthlessly. Am I right to think what I do? Have I listened to all the arguments against it? Have I thought deeply about it? Humility makes us great, not small. It makes us proud to be a voice in a choir.

Tendency to Ask Fundamental “Why?” Questions. “Why?” is subversive, and people are often frightened by questions without easy answers. Why are we doing it this way rather than that way? Why am I in this collaboration, and what does it exist for? Why aren’t we doing something else? Einstein said that as a boy he was in trouble all the time at school because the teachers accused him of asking stupid questions. When he became famous, he joked that now that everybody thought he was a genius, he was allowed to ask all the stupid questions he liked. Answers are a finite game; they’re played within boundaries, rules, and expectations. Questions are an infinite game; they play with the boundaries, they define them.

Ability to Reframe. Reframing refers to the ability to stand back from a situation and look for the bigger picture. One of the greatest problems of our world today is short-term thinking. As those of you from the business community know, most corporations keep an eye on three months down the road when the quarterly returns come in and shareholder value is paid out.

One executive I quote in my new book says, “We can’t afford to think about future generations because we have to think about our customers’ needs now and our profits now.” According to that executive, business is not a custodian for future generations. Education too has become consumed with short-term thinking, at least in England, where I live. By focusing on exams, schools are trying to measure the progress a child has made at the end of a year rather than cultivate his or her infinite potential as a human being.

BEHAVIORS BASED ON HIGHER MOTIVATIONS

Self-Awareness

- Has a sense of long-term goals and strategies

- Anticipates the impact of personal actions on others

- Assesses personal strengths and weaknesses in line with how others see them

Spontaneity

- Is prepared to experiment and take risks

- Is prepared to back a hunch or gut feeling about what will add value

- Actively seeks opportunities to have fun at work

Being Vision and Value-Led

- Expresses concern when the organization fails to live by its stated values

- Makes career choices guided by a desire to do something worthwhile

- Is prepared to fight for matters of principle

Holism

- Encourages people to understand the operation of the whole organization

- Anticipates the longer-term consequences of today’s actions and decisions

- Seeks to balance working and nonworking life

Compassion

- Considers the way external stakeholders will feel about actions or decisions the organization might take

- Tries to ensure the organization has a positive impact on the natural and social environments

- Is willing to make time to help others

Celebration of Diversity

- Seeks input from a wide range of people when planning or making decisions

- Respects and seriously considers ideas that challenge the mainstream

- Encourages people to express their individuality

Field Independence

- Listens to the views of others but is always prepared to take responsibility for personal decisions and actions

- Is not easily distracted when involved in an important task

- Is prepared to fight for a personal point of view when sure of its correctness

Humility

- Looks to give others credit for their knowledge and achievements

- Is prepared to explore what can be learned from personal mistakes

- Defers to the greater knowledge or experience of others

Tendency to Ask Fundamental “Why” Questions

- Makes sure to understand the causes of problems before initiating corrective action

- Gives others opportunities to explain their actions before giving negative feedback

- Looks for patterns behind problems and seeks to understand their origin or meaning

Ability to Reframe

- Brings a variety of approaches to problem-solving tasks

- Is prepared to let go of previously held ideas when these clearly are not working

- Seeks to broaden experience by taking on tasks outside of comfort zone

Positive Use of Adversity

- Seeks to learn from mistakes rather than blaming others for them

- Persists with a task in the face of difficulties

- Draws on hidden reserves of energy when things go wrong

Sense of Vocation

- Goes the extra mile to achieve an excellent result

- Sees work as an important part of life

- Expresses appreciation for the opportunities and gifts received at work and at home

Positive Use of Adversity. This principle is about owning, recognizing, accepting, and acknowledging mistakes. How many of us get trapped in courses of action because the initial step we took was a mistake and we didn’t want to lose face by admitting it? Rather than having the courage to acknowledge our error, we pursue the mistaken course of action, digging ourselves deeper into the mess. Have you ever admitted a mistake to someone where it really hurt to do so? Have you felt the energy flow out of you when you admitted it? I have learned a great deal from doing that. Great passion and energy can be released by saying the simple words “I made a mistake. What I did was wrong, and therefore I’m now going to embark on a different course.”

Positive use of adversity is also the ability to recognize that suffering is inevitable in life. There are painful things for human beings to deal with, yet they make us stronger, wiser, and braver. How boring we would be if we never had any adversity in our lives!

Sense of Vocation. This principle sums up spiritual intelligence and spiritual capital. Vocation comes from the Latin vocare, “to be called.” Originally, it referred to a priest’s calling to God. Today it often refers to the professions such as medicine, teaching, and law. It’s my ideal that business will become a vocation that appeals to people with a larger purpose and a desire to make wealth that benefits not only those who create it but also the community and the world.

Changing Human Behavior

In his book Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World (Irwin McGraw-Hill, 2000), John Sterman provides a blueprint for how to make a system work effectively. But, he points out, only if the people in a system behave as they should will the system work as it should. Most systems have the same failing — human behavior.

If we want to change systems, we have to change human behavior. But human behavior is not so easily changed. To achieve real transformation, we have to change the motivations that drive behavior. Today business, politics, education, and society in general are driven by four negative motivations: fear, greed, anger, and self-assertion. When we are controlled by these negative emotions, we trust both ourselves and others less, and we tend to act from a small place inside ourselves.

We can change our motivations to more positive ones by applying the 12 principles of SQ. I use the analogy of a pinball machine to explain attractors, a concept from chaos theory. Attractors are points that either collect energy or disperse it. In a pinball machine, the attractors are the little pits into which the steel balls fall. Our motivations are like these pits, and the steel balls are our behaviors. If you want to move the balls in a pinball machine, you pull back the spring and shoot another ball into the system, causing everything to fly and relocate.

Pumping spiritual intelligence into our motivational system works the same way. It knocks the balls out of their current motivational pockets and allows them to relocate. In this way, when we apply the 12 principles of spiritual transformation to our collaborations and our lives, self-assertion becomes exploration, anger becomes cooperation, craving becomes self-control, fear becomes mastery, and so forth. As we raise our motivations, our behavior changes. As our behavior changes, our results change, as well as the whole purpose and meaning of our collaborations (see “Behaviors Based on Higher Motivations” on p. 5).

People may accuse us of being naively hopeful to think that we can make the world a better place. I like to think of the poem that Mother Teresa posted in the orphanage she founded in Calcutta (the source is unknown):

People are often unreasonable, illogical, and self-centered. Forgive them anyway. If you are kind, people may accuse you of selfish ulterior motives. Be kind anyway. If you are successful, you will win some false friends and some true enemies. Succeed anyway. If you are honest and frank, people may cheat you. Be honest and frank anyway. What you spend years building, someone may destroy overnight. Build anyway. If you find serenity in happiness, people may be jealous. Be happy anyway. The good you do today, people will often forget tomorrow. Do good anyway. Give the world the best you have, and it may never be enough. But give the world the best you’ve got anyway. You see, in the final analysis, it is all between you and God; it was never between you and them anyway.

God in Mother Teresa’s poem was the Christian god. God for me is whatever any of us holds most sacred. I think that great collaborations can confer an I-Thou quality on our relationship to ourselves, to each other, to the community, and to the world. The word collaboration comes from the Latin word labore. There’s a very famous monkish motto from the Middle Ages: Labore est orare. To labor is to pray. Let our collaborations be our prayers.

Danah Zohar (dzohar@dzohar.com) is a physicist, philosopher, and management thought leader who advises global companies. She is the coauthor of Spiritual Capital: Wealth We Can Live By (BerrettKoehler, 2004).

NEXT STEPS

- Analyze what your organization does to build the three kinds of capital that Danah Zohar describes: material, social, and spiritual. If the enterprise is missing one of these forms of capital, what is the impact on the organization, the individuals within it, and outside stakeholders?

- Look at what motivates people in your organization. Do they generally operate out of fear, craving, anger, and self-assertion or mastery, self-control, cooperation, and exploration? Why is this the case? What impact does it have on how people work together?

- Consider the timeframe on which your organization bases its decisions and concept of success. How could you reframe thinking to be more holistic and take into consideration the long-term impact of decision-making? What might the effect be on the organization’s practices and principles?

—Janice Molloy