Imagine you have two new direct reports, Stan and Frank. Both seem equally qualified — a degree from a good school, a couple years of solid business experience, and youthful enthusiasm. You want to fill an upcoming opening in a management position, but you aren’t quite sure which one is the best candidate. You want to be as objective as possible in your recommendation, so you decide to encourage both of them and see which one demonstrates the most ability.

After a couple of weeks, Stan has gotten a jump start on the latest assignment and is doing a stellar job. Frank was out with the flu, so when he comes back, he’s a little bit behind. You keep your eye on him and continue to encourage him, but you really start to focus on Stan. Before you know it, you’re giving him more and more responsibility, and he does exceedingly well each time. Frank is doing adequately, but for some reason, you just don’t feel like he has that extra “umph.” Since you already have a “hot one” on your hands, you feel it’s not as necessary to invest as much time and energy in him.

In time, you promote Stan into the management position and pat yourself on the back for having picked the right person from the beginning. Frank, in your assessment, turned out to be just an average performer. But is that really the case?

Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

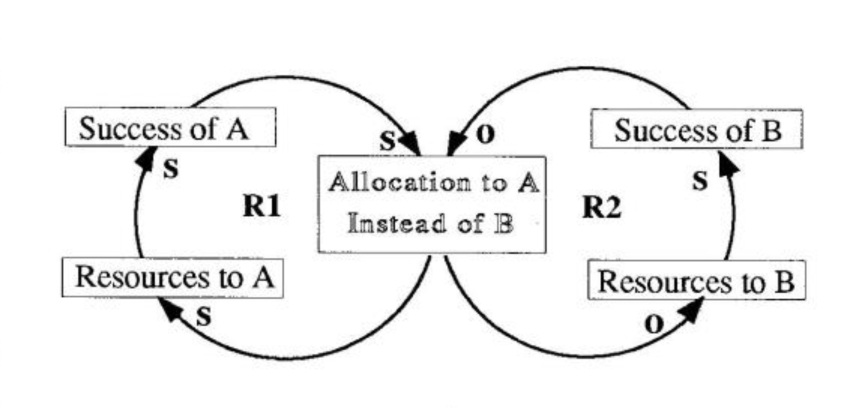

The “Success to the Successful” archetype suggests that success may depend as much on structural forces as innate ability or talent (see “Success to the Successful Template”). The performance of individuals or teams is often the result of the structure they are put in which forces them to compete for a limited resource such as a manager’s time, a company’s investments, or training facilities.

Success to the Successful Template

Assuming both groups (or individuals) are equally capable, if one person or group (A) is given more resources, it R2 has a higher likelihood of succeeding than B. That initial success justifies devoting more resources to A and robs B of further resources (R1). As B gets less resources, its success diminishes, which further reinforces the “bet on the winner” allocation of resources (R2). The structure continues to reinforce the success of one, and the eventual demise of the other.

“Success to the Successful” is an archetypal case of self-fulfilling prophecies. The outcome of a situation is highly dependent on the initial conditions (or expectations) and whether they favor one party or the other. If B had received more resources in the beginning, the roles would be reversed: B’s success would increase, and A would suffer.

In effect, our mental model of what we believe will determine success shapes the very success we seek to assess. In the case of Stan and Frank, the manager may not have had a strong feeling either way in the beginning. But initial events—Stan’s success with the first project and Frank’s illness — quickly became the shaper of his expectations and actions, reinforcing what he later believed to be an objective assessment that Stan was “right” for the job.

Balancing Work and Family

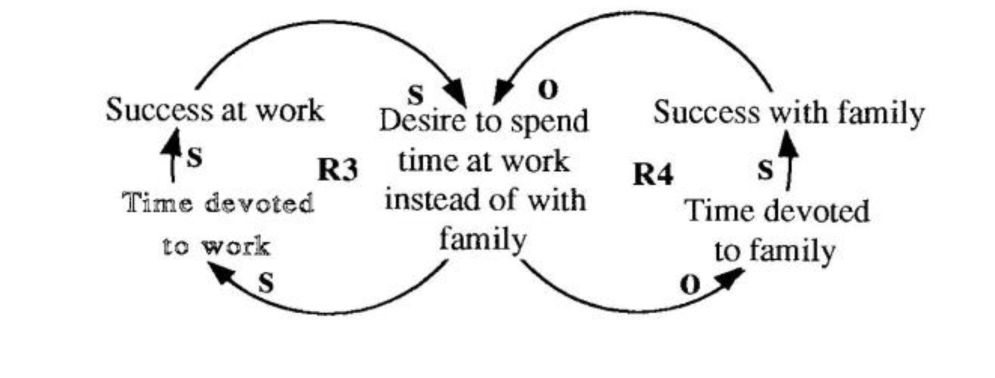

The tension between work and family is another example of the “Success to the Successful” archetype (see “Balancing Work and Family” diagram). We each have a certain amount of time and attention available. The more we devote to work, the more successful we may become, which fuels the desire to put more time into work (R3). A similar result occurs if we devote our energy to our family (R4). Most of us struggle to maintain a balance between the two.

Suppose, however, that a large project forces you to put in long hours at work for an extended period of time. The time away from the family begins to create tension at home. Your family complains that you are never around. But when you do come home, you get hit with all of the problems that have been accumulating. So you withdraw further from your family, devoting yourself even more to the project. Your work on the project is starting to generate interest throughout the company. At the same time that praise at work is building, the complaints at home are piling up, driving you further from your family. The two situations mutually feed each other — the downward spiral of one, and the upward spiral of the other.

Rewriting the Prophecies

The “Success to the Successful” archetype highlights how success can be determined by initial chance and how the structure can systematically eliminate the other possibilities that may have been equally viable (or even superior). If we are not conscious of being in this archetype, we become a victim of its structure, which continually pushes us to do whatever has been successful in the past. After a while, the choice between work and family doesn’t seem like a choice anymore — the structure has determined the outcome.

As in most of the archetypes, managing a “Success to the Successful” situation requires looking at it from a more macro level and asking ourselves “what is the larger goal within which the situation is embedded?” In the case of work vs. family, a larger goal that includes both of them, such as, “I seek a balance between my success at work and time with my family,” must guide the daily decisions. In the case of the two proteges, the goal might be to provide an environment in which the full potential of both employees can be developed. Without the guidance of a larger goal, the structure will continue to dictate your actions.

Creating Environments for Success

At the heart of the “Success to the Successful” archetype lies the competitive model of Western economics which is characterized by a win-lose philosophy. An implicit assumption of the competitive model is that whoever wins must, by default, be the best. In reality, however, it may not be the individuals, but the structure they are in that determines the “winner.” The assumption here is that you need a competitive environment out of which the best candidates will somehow surface.

Balancing Work and Family

A fundamental question that the archetype begs us to ask is why put two groups or individuals into the structure in the rust place? If we want a single “winner,” why not put our energies towards understanding what it takes to develop such a winner? We can then focus our energy and resources on that person or project from the beginning rather than waste time, money, and morale by stringing along multiple people and projects. We can, in effect, lop off the other half of the “Success to the Successful” archetype. Instead of diverting resources and systematically letting other groups to fail, we can focus all our efforts and resources on finding ways to build a supportive environment for success.

A way to break out of the “Success to the Successful” archetype is to get rid of its competitive structure and find ways to make teams collaborators rather than competitors. Many Japanese companies, for example, often have multiple project teams working on the same design. Unlike American companies, however, the goal is not to compete against each other and have one team’s design win. AU of the teams are seen as part of the same larger effort to develop the best design for the company. The teams collaborate with each other, sharing ideas and information, and produce a design that may be a combination of innovations from each of the groups.

The “Success to the Successful” archetype highlights the need for creating a win-win environment where cooperation replaces competition and where creating an environment for success is more important than trying to identify successful individuals. In fact, that’s what good academic institutions provide, and ultimately what good corporate environments should provide — an environment in which all their people can thrive and contribute their unique talents.”

Success to the Successful” and other templates can be found in The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge (Doubleday).