Most people are familiar with the Sufi tale of the four blind men, each of whom is attempting (unsuccessfully) to describe what an elephant is like based on the part of the animal he is touching. Trying to understand what is going on in an organization often seems like a corporate version of that story. Most organizations are so large that people only see a small piece of the whole, which creates a skewed picture of the larger enterprise. In order to learn as an organization, we need to find ways to build better collective understanding of the larger whole by integrating individual pieces into a complete picture of the corporate “elephant.”

A Starting Point for Theory-Building

Quality pioneer Dr. Edwards Deming once said, “No theory, no learning.” In order to make sense of our experience of the world, we must be able to relate that experience to some coherent explanatory story. Without a working theory, we have no means to integrate our differing experiences into a common picture. In the absence of full knowledge about a system, we must create a theory about what we don’t know, based on what we currently do know.

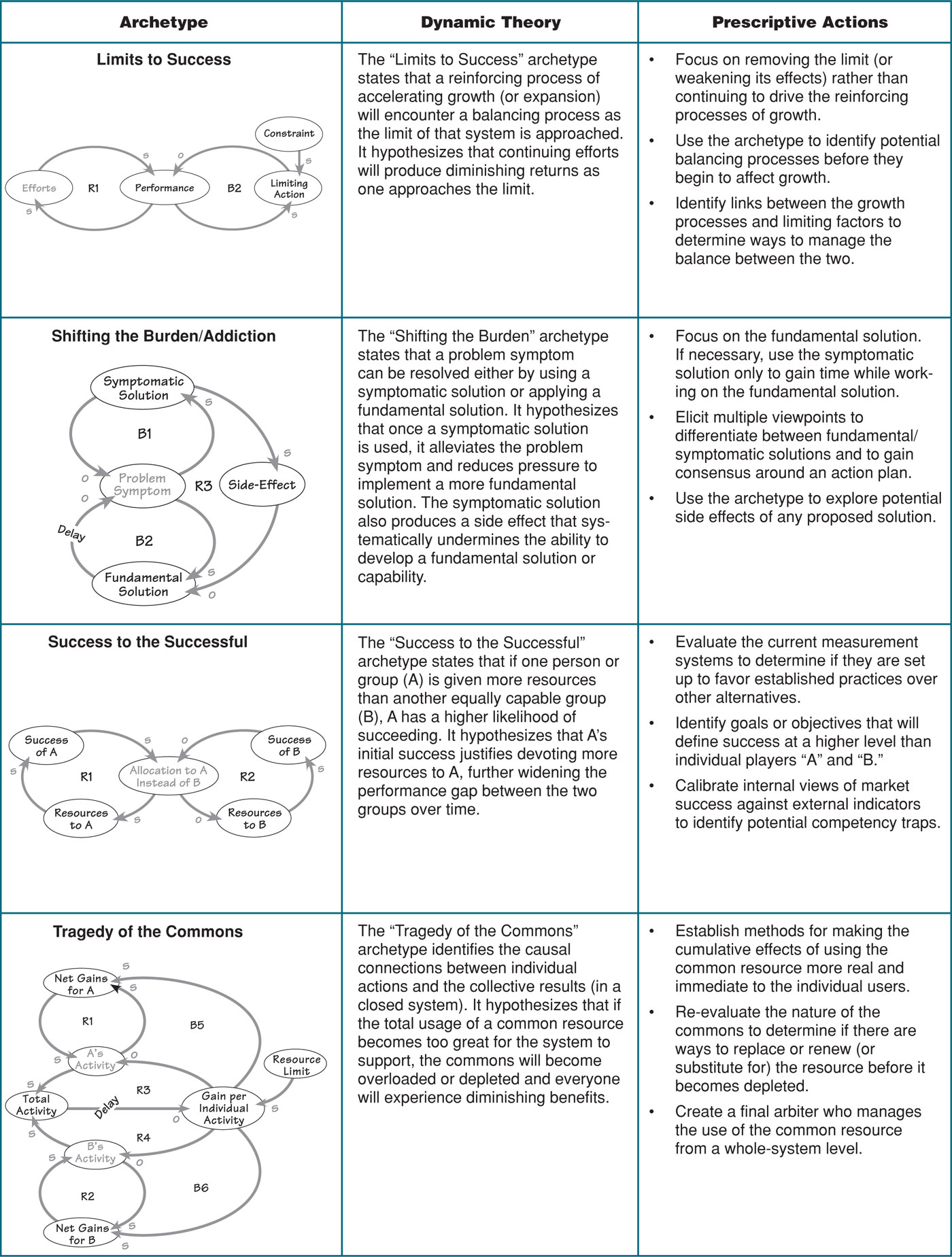

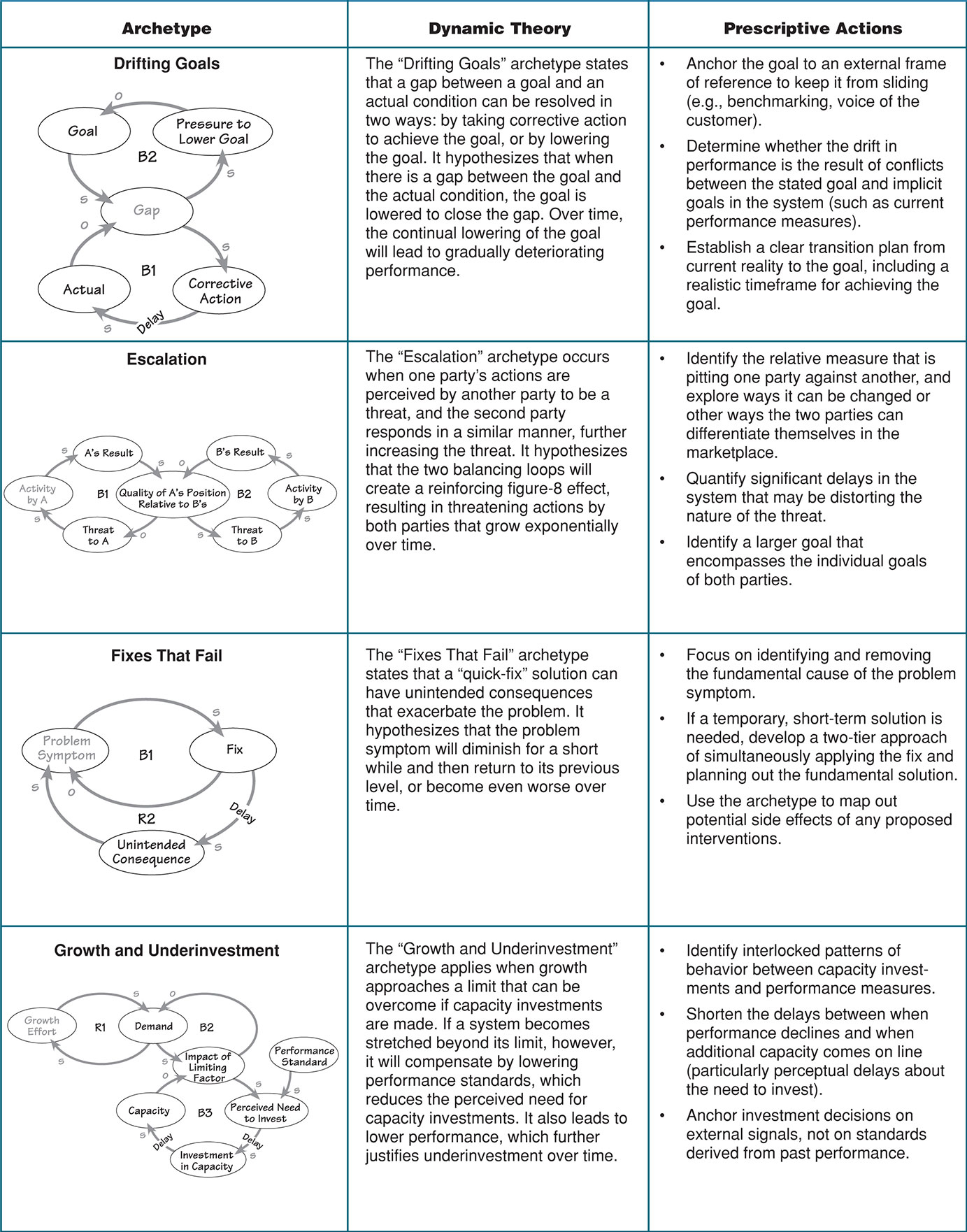

Each systems archetype embodies a particular theory about dynamic behavior that can serve as a starting point for selecting and formulating raw data into a coherent set of interrelationships. Once those relationships are made explicit and precise, the “theory” of the archetype can then further guide us in our data-gathering process to test the causal relationships through direct observation, data analysis, or group deliberation.

Each systems archetype also offers prescriptions for effective action. When we recognize a specific archetype at work, we can use the theory of that archetype to begin exploring that particular system or problem and work toward an intervention.

For example, if we are looking at a potential “Limits to Success” situation, the theory of that archetype suggests eliminating the potential balancing processes that are constraining growth, rather than pushing harder on the growth processes. Similarly, the “Shifting the Burden” theory warns against the possibility of a short-term fix becoming entrenched as an addictive pattern (see “Archetypes as Dynamic Theories” on pp. 9–10 for a list of each archetype and its corresponding theory).

Systems archetypes thus provide a good starting theory from which we can develop further insights into the nature of a particular system. The diagram that results from working with an archetype should not be viewed as the “truth,” however, but rather a good working model of what we know at any point in time. As an illustration, let’s look at how the “Success to the Successful” archetype can be used to create a working theory of an issue of technology transfer.

, “Success to the Successful” Example

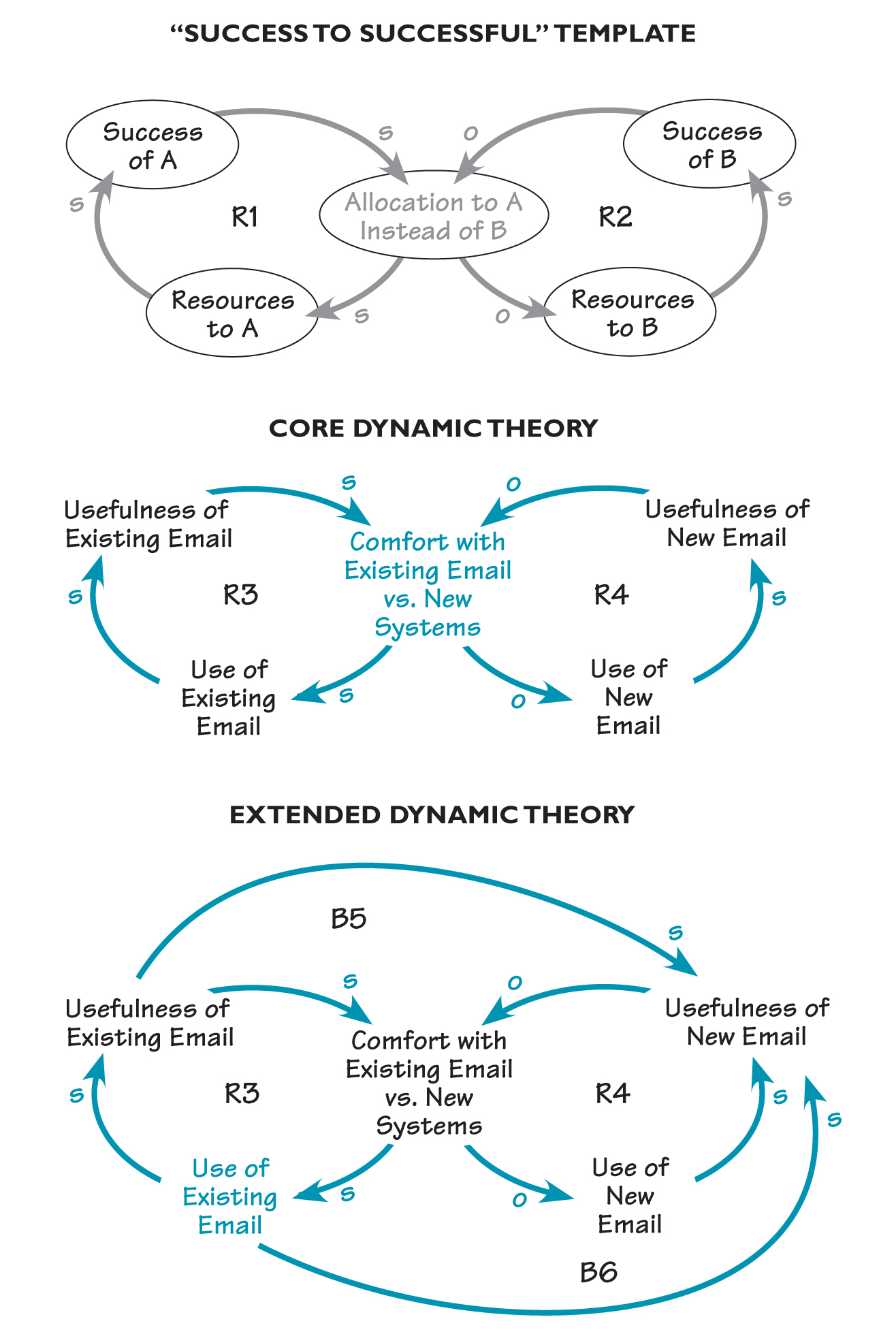

An information systems (IS) group inside a large organization was having problems introducing a new email system to enhance company communications. Although the new system was much more efficient and reliable, very few people in the company were willing to switch from their existing email systems. The situation sounded like a “Success to the Successful” structure, so the group chose that archetype as its starting point.

'SUCCESS TO SUCCESSFUL' EMAIL

Starting with the “Success to the Successful” storyline (top), the IS team created a core dynamic theory linking the success of the old email systems with the success of the new system (middle). They then identified structural interventions they could make to use the success of the old systems to fuel the acceptance of the new one (loops B5 and B6, bottom).

The theory of this archetype (see “‘Success to the Successful’ Email” on p. 8) is that if one person, group, or idea (, “A”) is given more attention, resources, time, or practice than an alternative (, “B”), A will have a higher likelihood of succeeding than B (assuming that the two are more or less equal). The reason is that the initial success of A justifies devoting more of whatever is needed to keep A successful, usually at the expense of B (loop R1). As B gets fewer resources, B’s success continues to diminish, which further justifies allocating more resources to A (loop R2). The predicted outcome of this structure is that A will succeed and B will most likely fail.

When the IS team members mapped out their issue into this archetype, their experience corroborated the relationships identified in the loops (see “Core Dynamic Theory”). The archetype helped paint a common picture of the larger “elephant” that the group was dealing with, and clearly stated the problem: given that the existing email systems had such a head start in this structure, the attempts to convince people to use the new system were likely to fail.

Furthermore, the more time that passed, the harder it would be to ever shift from the existing systems to the new one.

Using the “Core Dynamic Theory” diagram as a common starting point, group members then explored how to use the success of the existing system to somehow drive the success of the new one (see “Extended Dynamic Theory”). They hypothesized that creating a link between “Usefulness of Existing Email” and “Usefulness of New Email” (loop B5) and/or a link between “Use of Existing Email” and “Usefulness of New Email” (loop B6) could create counterbalancing forces that would fuel the success loop of the new system. Their challenge thus became to find ways in which the current system could be used to help people appreciate the utility of the new system, rather than just trying to change their perceptions by pointing out the limitations of the existing system.

Managers As Researchers and Theory Builders

Total Quality tools such as statistical process control, Pareto charts, and check sheets enable frontline workers to become much more systematic in their problem solving and learning. With these tools, they become researchers and theory builders of their own production process, gaining insight into how the current systems work.

Similarly, systems archetypes can enable managers to become theory builders of the policy- and decision-making processes in their organizations, exploring why the systems behave the way they do. As the IS story illustrates, these archetypes can be used to create rich frameworks for continually testing strategies, policies, and decisions that then inform managers of improvements in the organization. Rather than simply applying generic theories and frameworks like Band-Aids on a company’s own specific issues, managers must take the best of the new ideas available and then build a workable theory for their own organization. Through an ongoing process of theory building, managers can develop an intuitive knowledge of why their organizations work the way they do, leading to more effective, coordinated action.

ARCHETYPES AS DYNAMIC THEORIES

Limits to success dynamic theory