The term “Compression” refers to the end of economic expansion as we currently know it, that is, ongoing growth enabled by the practices of the Industrial Revolution and powered mostly by fossil fuels. High-consumption industrial societies created many benefits we’d like to keep, but also huge problems that we cannot put off dealing with. To respond effectively to the “squeeze” we’ve put on the Earth’s resources and ecological viability, we also need to “compress” our work processes and products to make them less wasteful of human and natural resources. To meet these challenges, our organizations will need to engage in high rates of learning and achieve unprecedented levels of performance. The key to this major revolution is within each of us.

Our 21st-Century Challenges

In an age of Compression, all of these forces act at once. To get our minds around the enormity of this fact, not only do we need systems thinking, we need a system for systems thinking. This kind of thinking is not normal in today’s organizations. We have to learn it, and to learn it, we have to practice it.

Without taking a systems approach, well-intentioned, intelligent people grab for magic solutions to our environmental messes, such as seeding the oceans with iron to sequester carbon, creating sulfuric clouds in the sky to reflect solar heat, or pumping CO2 into the ground for storage. Because they have faith in technology, they jump on these ideas, seemingly unaware that the unintended consequences of such actions could be catastrophic. But it’s easy to see how each of these actions could backfire. Most of our messes today are the unintended consequences of past “solutions.”

Global Objective in Compression

To begin to approach this confluence of issues more systemically, we propose setting a measurable baseline objective:

By the year 2040, create a quality of life around the globe that is equivalent to that of today’s industrial societies while consuming less than half the energy and less than half the virgin raw materials as were consumed in the year 2000, with near-zero toxic releases.

OUR 21ST CENTURY CHALLENGES

To achieve this objective, people in both advanced and less-advanced economies must learn to make much better use (and reuse) of resources. The truth is, though, that these standards can’t be uniformly applied to every part of the world. Those barely surviving can hardly consume less than they currently do. Because industrial economies consume significantly more materials and energy than other economies, the cuts in those regions need to be deeper. Fortunately, they also have more innovative technological research with which to meet this tough goal. These kinds of initiatives are starting to become reality, not vague hope. For example, several years ago, the British Parliament enacted the Climate Change Act of 2008, setting timetables toward an 80 percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Of course, to achieve these goals, we need to go beyond basics like reduce, reuse, recycle. We currently have too few inventive, innovative organizations with business models that allow them to be viable while processing less material and energy, not more. A transformation is unlikely to occur by gradually raising performance bars through regulation, with governments coercing the reluctant to meet minimum standards. Instead, we need to create what I call “Vigorous Learning Enterprises.”

Vigorous Learning Enterprises

VIGOROUS LEARNING ENTERPRISES

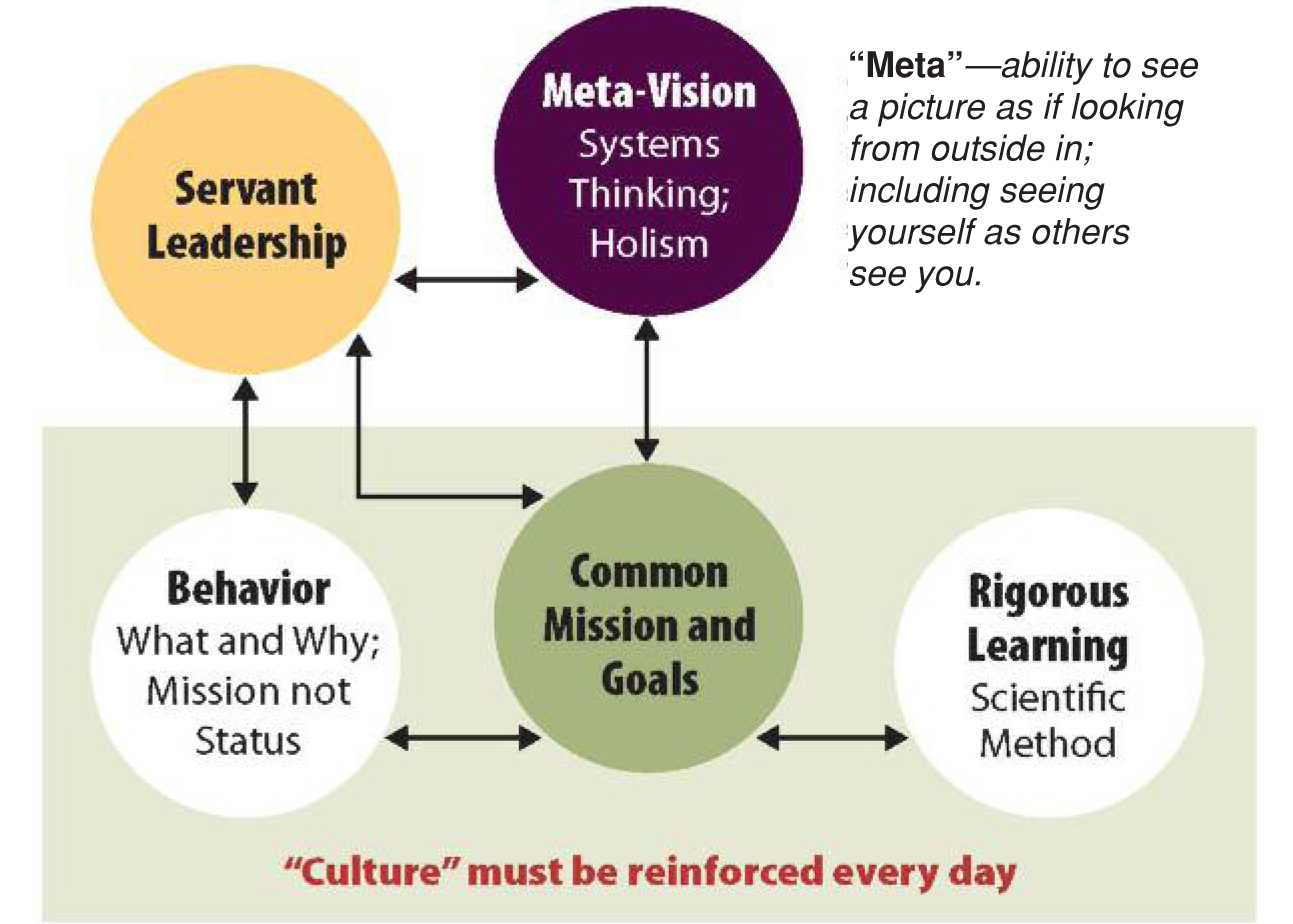

- Meta-Vision, or keen, broad system insight, especially by leaders.

- Common mission and goals related to Compression, that unifies effort.

- Systems and structure for rigorous learning built into regular work for everyone, not for just a few people.

- Behavior for learning; ability to subdue personal infighting to concentrate on problems and issues.

- Servant leadership, putting the mission, organization, and development of it people before personal gain or ego.

All this is possible, but so contrary to instinct that this culture needs a built-in mechanism that reinforces behavior almost daily.

What is a Vigorous Learning Enterprise? Vigorous implies that an organization “does” something. It’s not strictly academic or social. Those most critical are in mining, agriculture, food processing, manufacturing, utilities, healthcare, police, fire, justice, and so on. They either process large amounts of energy and material (and are thus gatekeepers of our consumption), or they provide services that are crucial to the quality of life. A rough estimate is that 30-40 percent of the American workforce is engaged in such work — a high percentage, but not everyone.

Learning is the act, process, or experience of gaining knowledge or skill. In an organizational setting, it includes process learning, innovation, and organizational learning.

Enterprise is used in many senses, but the intent here is analogous to the supply chain: several tiers of customer organizations going out and several tiers of suppliers feeding in, plus feeder educational institutions, consultants, advisors, banks, auditors, and the like.

Here are some principles and practices for Vigorous Learning Enterprises:

- They are mission-driven. Serving a social need or mission has to trump all other objectives, including growth, profit maximization, job creation, and personal aggrandizement. The turning point for leaders is realizing that their organization must support nature; nature does not exist to support or enrich them. That shift changes the emphasis from what we get to what we do. The actions by BP and other companies involved in the Gulf oil blowout illustrate why this change in focus is important. Attempting to limit liability — the basis of corporate charters — is a dysfunctional way of dealing with such problems.

- They look at their physical processes. When we move away from focusing on what we get, we can more objectively look at physical processes: how our customers act, what our workers do, and how our business models operate. When we identify our primary customers’ real needs, we recognize that anything else is waste. Lean thinking identifies waste as what a customer will not pay for. In Compression Thinking, we go a step further and identify waste as any unnecessary use or destruction of resources, things that nature should not have to “pay for.”

- They expand their cognition (meta-vision). By expanding our view, we can both improve local processes and anticipate effects far removed in time and distance.

- They extend the concept of “waste.” The concepts of eliminating waste that are a part of lean today are typically confined to a few elements of operations and never applied to full life cycles. By expanding the definition of “waste” to include materials, energy, space, and unproductive behaviors, we can define elimination of waste as doing whatever is necessary by the lowest energy process we can devise. Low energy use is usually associated with low use of all resources.

- They value quality over quantity. This new kind of organization values quality over quantity; provides service, not promotions to buy more “stuff”; does it right the first time; and emphasizes prevention over remediation. As Yogi Berra might say it, “Fix it before it happens.”

- They avoid “model myopia.” We need to learn to look at what really goes on in our organizations without the prejudice of model blinders, including all the financial ones. We’ve hitched our guidance systems to obsolete measurement models. Even customer- centered lean operations typically conflict with accounting models. Physical measurements of what we do are far from perfect, but they beat self-referencing measures based only on human valuations, which is what market-derived dollar measures have been.

- They develop rigorous structures for learning. Systems structured on the basics of the quality movement are a good start, but few manage to spread throughout the entire organization. Also, sustaining the behavior is challenging, especially when issues are “wicked,” meaning that people perceive them from different tunnel visions or conflicting spheres of interest. To make a new culture “stick,” the organization needs codes of conduct with daily reinforcement built in, or human nature will take over and undermine the system. In this sense, we’re really trying to elevate our level of civility, at least in our work settings.

- They create “tribal cohesion.” We must create a sense of cohesion — trust and confidence — across work enterprises, including suppliers and customers, while minimizing “tribal rivalries.” These arise from more than ethnic and religious differences. They include functional silos, intellectual property divides, and races for reward and recognition. Rivalry and competition are instinctive, but cohesion is vital for true information sharing to occur. Everyone has to be confident that all share a common allegiance to a universal mission. No working organization today functions at the level of a vigorous learning enterprise, but some of our best organizations have mastered big chunks of the skills and culture required. These rigorous organizational cultures demand the highest levels of professionalism. Is this impossible? No. Is it difficult? Yes.

New Business Model

One of the most counterintuitive aspects of coping with Compression is the need to rethink the business model so that an organization can be viable without focusing on selling more, more, more. DTE Energy (Detroit) is one of the more aggressive utilities in helping customers reduce their energy usage. By doing so, the company reduces costs for its clients, many of whom are struggling financially, and eliminates the need to expand its energy capacity. An overview of how DTE helps customers save energy is available at www.dteenergy.com/ businessCustomers/saveEnergy. PortionPac Chemical in Chicago also has a business model that foreshadows those of the future. PortionPac primarily produces cleaning chemicals, but it sells few of these products directly. Instead, it provides service contracts, so customers pay for clean buildings, not cleaning products per se. After signing on a customer, PortionPac trains the client’s cleaning personnel in methods that are designed to minimize the use of detergents and other chemicals. (Excess cleaning chemicals are a major source of problems for sewage plants and of pollution in waterways.) Over six months or so, a new client’s use of cleaning chemicals usually drops by 40-50 percent. The less product PortionPac ships, the higher the margin it earns on the service contract.

This approach makes conventional business sense, but PortionPac is also on a mission to increase the respect given to cleaning personnel, who are usually poorly paid and whose role in an organization is often ignored. The goal is for cleaning personnel to contribute to reducing or eliminating the pollution a company generates, and thereby reducing the pollution of whole cities or regions. Cleaners see what others don’t, so PortionPac can help clients examine their waste streams to see ways to reduce waste of materials and toxic releases.

DTE Energy and PortionPac are on the way to becoming Vigorous Learning Enterprises. By placing a strong emphasis on developing people and, in turn, expecting extraordinary performance, these organizations clash with current assumptions both for business and government.

Mission First

Leaders become teachers, mentors, and role models — rather than central decision makers who stand in the way of learning — to create a top-performance organization.

Think of the organization’s primary purpose as performance to mission, not maximizing profit, soaking up employment, serving as an owner’s personal fiefdom, or other ulterior motives. Making this shift is obviously the big hurdle. However, transforming working organizations, as wild as that idea may seem, has more promise than trying to shift public policy. Working organizations are not democracies, with everyone doing as they please. For good or bad, companies, nonprofit hospitals, and military units are disciplined organizations.

People’s behavior changes when the environment in which they function changes. If companies change what they do and how they do it, the working culture slowly changes with it. No other avenue of social change seems to offer this possibility.

But to spearhead such a change, leaders of a working organization must absorb the thinking and work on a sequence of change that moves the company in a direction that can deal with Compression. Leaders start with themselves, becoming role models of the discipline and behavior they expect from others. That’s servant leadership, not status-based leadership. Probably the most succinct description of servant leadership comes from the military: Mission first. Troops second. Me third.

Global Objective in Compression

Sometimes control-oriented leaders of no-nonsense organizations regard concepts and methods for open dialogue and self-initiative as “permissive management.” But a Vigorous Learning Enterprise is the opposite. Leaders demand that all employees develop themselves, individually and collectively, into the very best of what they are capable. Leaders become teachers, mentors, and role models — rather than central decision makers who stand in the way of learning — to create a top-performance organization.

The human challenge — rapidly changing ourselves and our organizations — is the greatest one we face, but it’s the key to meeting all other challenges. Compression compels us to have same spirit of the race to put a man on the moon, but with a lot more of us actively participating in this common mission. This time, the stakes are even higher.