Transforming a large, successful organization with facilities around the world to meet the needs of a changing market is a challenging undertaking. But several years ago, Nortel Networks’ executive team concluded that, to remain successful, the company needed to integrate its product lines more closely. To accomplish this major overhaul, Nortel focused on three key areas of change: processes, technology, and people.

Not surprisingly, the people part of the triad proved to be the most crucial. Everything else hinged on employees’ willingness and ability to implement the new processes and technology. Nortel used a computer simulation of the organizational change process, built around new ideas about how ideas spread, to help change agents design effective ways for educating employees about the benefits of the integrated strategy.

Recruiting “Ambassadors”

Nortel is a leading data and telecommunications supplier and manufacturer, with over 80,000 employees worldwide and markets on all continents. In 1996, the company consisted of five lines of business (LOBs)—separately serving the needs of data, voice, public, private, and wireless networks—each with its own products, processes, and delivery mechanisms. The individual LOBs had order-management and order-delivery systems that worked well for them. However, this set-up was not conducive to supplying customers with networks that integrated products from multiple LOBs. At the time, a minority of customers ordered integrated networks. However, the market was shifting, and Nortel anticipated the need to integrate products from its LOBs.

In August 1996, Nortel officially launched its Supply Chain Management (SCM) program to address its customers’ future needs for integrated network solutions. The goal of the initiative was to present customers with a single interface to make it easier for them to order products for integrated voice and data networks from across the LOBs.

The SCM executive sponsor and his team created a vision of how the future supply chain would function and assigned a three-person management team to oversee the organizational change, training, and communication efforts around the vision. This team then recruited people from the 28 Nortel locations worldwide to serve as “Ambassadors of Change.” Ambassadors were members of their local SCM implementation teams with training or communications responsibilities for their sites. Initially, there were 37 ambassadors; this number eventually grew to about 150.

The Ambassadors’ mission was to engage employees in adapting and adopting the SCM vision as their own. The Ambassadors sought more than simple buy-in by local units; they wanted to cultivate among employees a real sense of ownership for the new systems and recognition that SCM was the right thing to do.

The Ambassadors soon faced their first challenge: People within each LOB saw their own processes as working well. Without a sense that anything was “broken,” many people found it difficult to accept the need for change and to take a broader view of their role in the system as a whole. At first, the Ambassadors did not have the tools to overcome this resistance, but that was soon to change.

Introducing “The Tipping Point”

In October 1997, Nortel sponsored a “Change Leaders’ Conference.” The event offered those involved in training, organizational development, and various change initiatives throughout the company a chance to learn from each other’s successes. Among the 80 participants were 20 or more of the Ambassadors, along with the three-person corporate leadership team.

The program included hands-on experience with The Tipping Point, a computer simulation of the organizational change process. This management flight simulator uses the spread of disease through a population as an analogy for the spread of ideas through an organization. The structure of the simulation is based on both epidemiological and organizational development theory; the data that drives the model come from experiences at Nortel.

Within the simulation, advocates of new ideas—individuals who recognize the value of the organizational change and are enthusiastic about the effect it will have on their jobs—are analogous to people infected with a disease. In this case, their enthusiasm is quite literally infectious! Through word of mouth, advocates spread the news about the benefits of the initiative. The rate at which the information travels depends on the number of contacts between supporters of the change and those who are neutral about it. It also hinges on environmental factors like rewards and recognition for adopting the innovation, leaders who “walk the talk,” and infrastructure support for the new processes. As the number of advocates increases, it eventually reaches a critical mass, which causes the entire organization to “tip” rapidly toward supporting the new idea.

At the conference, about 20 teams vied with each other to design the best strategy for increasing the number of simulated advocates of a change initiative while keeping the simulated costs down. The charged atmosphere of the friendly competition catalyzed conversation about organizational change and gave people an opportunity to test their ideas. Many participants left the session with insights about applying this innovative model to their own change efforts (see “Testing Assumptions About Change”).

Spreading Commitment

For the Ambassadors, concepts from The Tipping Point not only helped to create a common language around change, they also became the building blocks for the people and organizational portion of the overall SCM implementation. The ideas that were most influential were: (1) the concept that “advocates” are people who accept and apply a change, (2) the importance of connections between advocates and others, and (3) the role that upper management plays by modeling desired behaviors.

For example, the Ambassadors used the language from The Tipping Point in their weekly planning sessions. They talked about “spreading the word” and set clear goals around the number of contacts they wanted to foster between advocates and those not yet “infected” at each location. The Ambassadors created situations for advocates to meet with people who needed to be “exposed” to the new ideas; for instance, a “road show” that introduced all employees in Latin America to the SCM vision. This process set the stage for the traditional educational programs and internal marketing of SCM that followed.

The three-person management team also used the simulation with top management. For the SCM executive sponsor, this experience reinforced the value of using a common language to discuss SCM implementation and the informal manner in which ideas spread throughout an organization. He identified ways that he could help foster commitment by walking the talk and by taking advantage of the power of his position; for example, by sending personal thank-you notes for jobs well done during the transition.

Overcoming Resistance

The Ambassadors did encounter some resistance to their approach. In one case, an Ambassador felt that she was not getting through to the leader of her implementation team. The group was planning to embark on a traditional roll-out, which consisted mostly of printed material and some general training, and did not rely on encouraging contacts between advocates and others. The Ambassador appealed to the program’s leaders for assistance. Together they presented The Tipping Point to the implementation team. The participants became quite involved with the game and engaged in heated debate about their simulated strategies.

Days later, the implementation team changed its approach to communicating with the workforce about the SCM implementation to be more consistent with the strategy designed by the Ambassadors. The simulation did not teach the group anything new; rather they themselves learned which approaches might be most effective by talking through their simulated strategy while playing the game.

TESTING ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT CHANGET

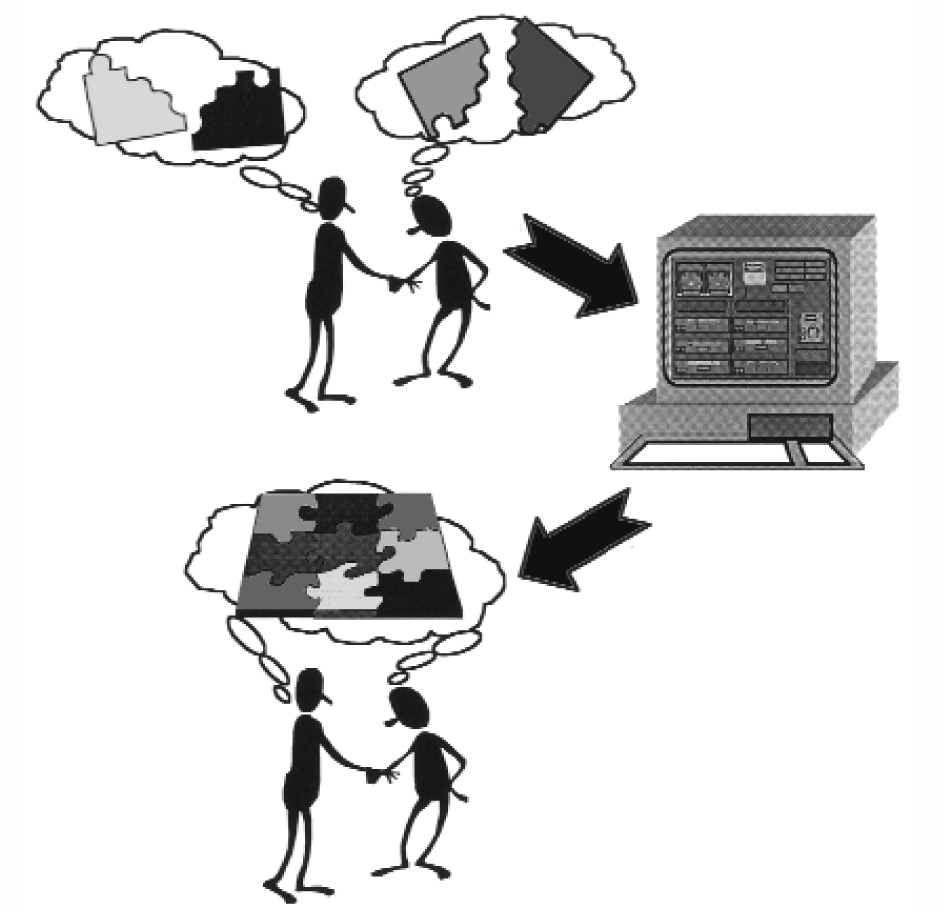

Two change agents have different ideas about how to convince employees to embrace a new initiative. By using a simulation like The Tipping Point, they are able to share their own “pieces of the puzzle,” test their assumptions, and gain a more complete understanding of the change process.

In early stages of the SCM implementation, some sites experienced technology difficulties. The Ambassadors’ enthusiasm and commitment was instrumental in bolstering morale and in keeping people focused on the goal. The Ambassadors from those locations documented valuable “lessons learned” that they passed on to sites implementing SCM later in the cycle.

At Nortel, creating the Ambassadors of Change was an important first step in shifting from an emphasis on optimizing local processes to a systemic view of the company as a whole. The Tipping Point simulation provided the Ambassadors with a common language for talking about organizational change and an opportunity to experience the value of creating connections to foster change. The change agents were then able to develop effective ways to foster “infectious” enthusiasm among employees about the shifts in strategy that would enable the company to prosper in the 21st century.

Carol E. Lorenz, Ph. D., (lorenzc@mindspring.com) worked for Nortel Networks from 1984 through 1999, most recently as director of organizational change for global operations. After leaving Nortel, Carol started Carol Lorenz and Associates, offering consulting and contracting services in the area of organizational effectiveness. Andrea Shapiro, Ph. D., (andjoy@mindspring.com) is an independent consultant whose work emphasizes organizational learning and systems thinking. She has worked as a software designer and has written traditional and system dynamics models of business problems, including The Tipping Point. For information on purchasing The Tipping Point simulation, contact Resources Connection at info@resourcesconnect.com.