People in Guatemala—smart people—were working harder, hiring brighter people, raising more money, doing better projects, and getting improved results. And yet, what they sought to eliminate—poverty— was getting worse. So, we asked what we thought was a relatively straightforward question: “Do you understand the fundamental dynamics of poverty?” As it turned out, no one had an answer— not the government, NGOs, local communities, or business leaders.

We set out with CARE Latin America to understand this complex problem. We engaged leaders of the national intelligence service and the military policy and leadership institutes, on the one hand, and members of the former guerrilla movement, on the other; leaders of the Catholic church and the leading Mayan philosophers; the head of the president’s commission on local economic development and leaders in local villages; in total, 30 diverse, sometimes historically conflicted, perspectives.

TEAM TIP

When people are working harder and yet a problem symptom fails to improve, ask, “Do we understand the fundamental dynamics of [the problem]?” Use some of the tools in this article to improve your knowledge of the system.

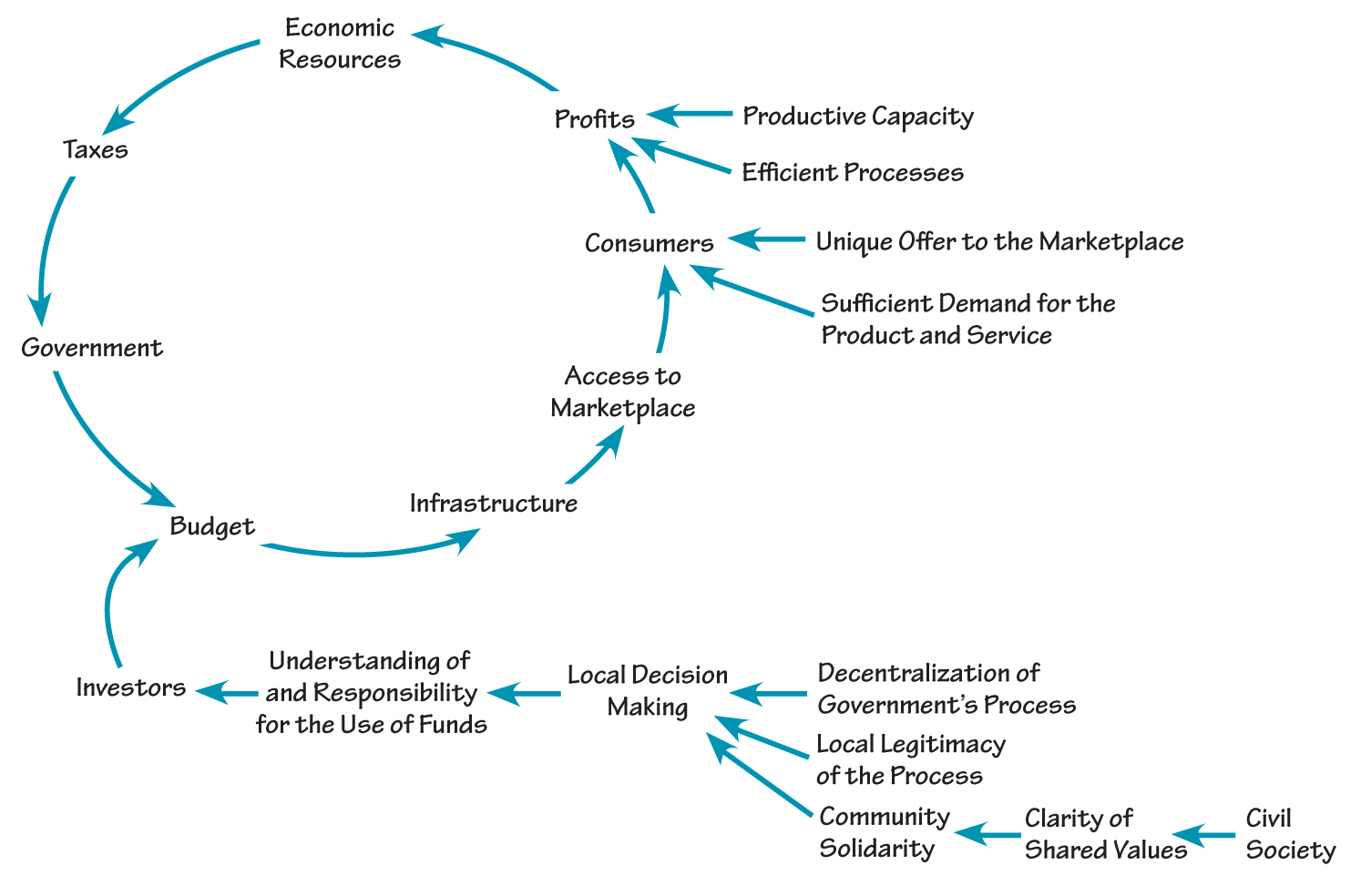

Many thought it would be impossible for these diverse actors to come together in the same room; for them to reach shared understanding about the impact they each had on their world; and for them to agree about how to act together to change their world for the better. Yet, in a surprisingly short time, by integrating principles and practices from systems thinking and system dynamics with those rooted in group dynamics and collaboration building, representatives from these stakeholder groups were able to create a simple, one-page representation—an integrated systems map—that they all agreed represented their world. This map included all of the system’s parts, their interactions, and their goals. It clearly showed why the groups were experiencing conflict and what they needed to do about it. Representatives then came to shared agreement about the overall goal of their collective work. And they identified a handful of critical resources that would enable them to move it in the direction they all want it to go.

Naturally, several questions come to mind. How did they make such a major shift in such a short time? Can this success be replicated? Can it be scaled? In the spirit of Peter Block, the answer to all these questions is “yes” (see The Answer to How is Yes, Berrett Koehler, 2001).

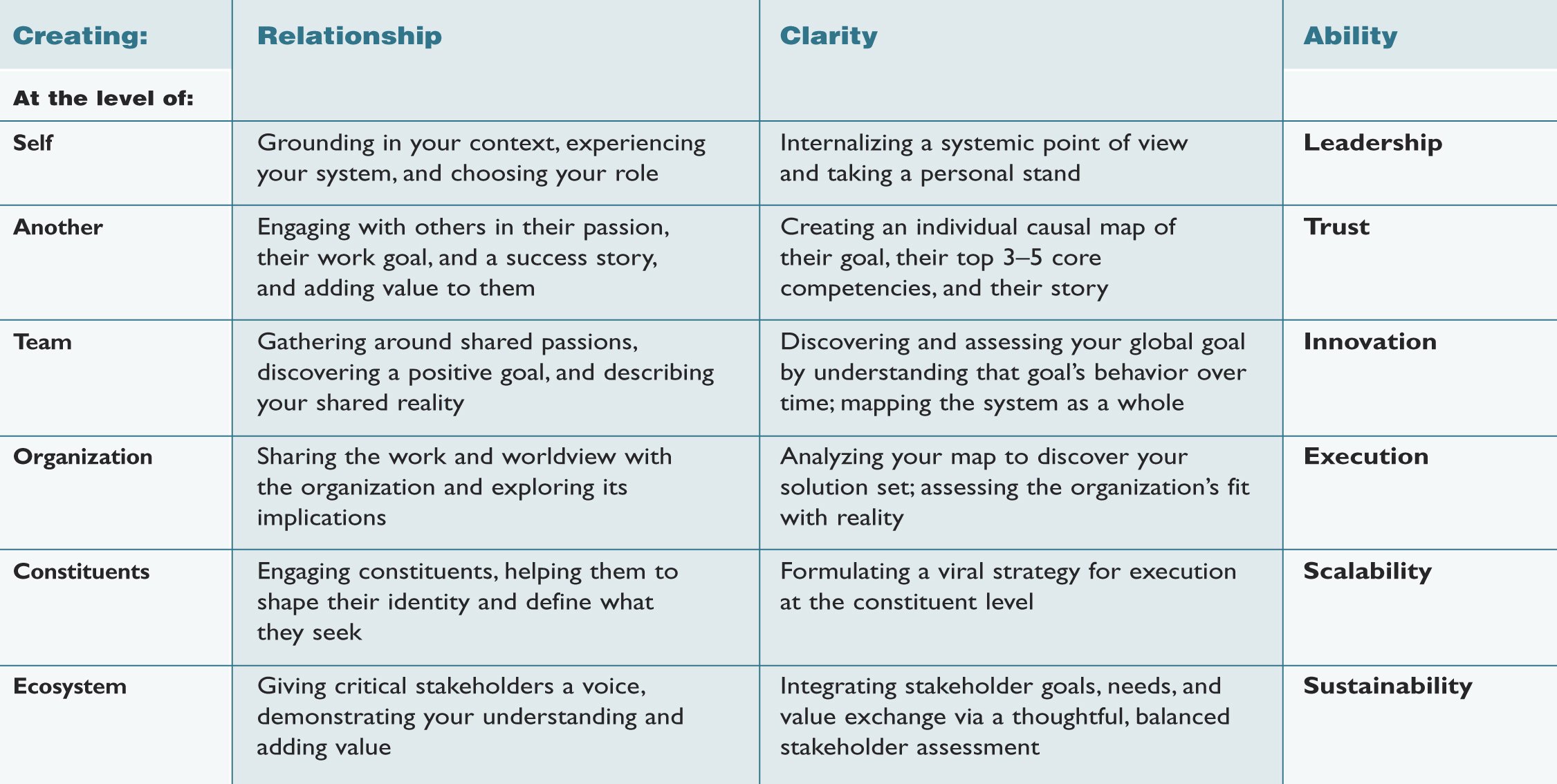

Broadly speaking, the group achieved success by focusing on building relationships and developing clarity, first as individuals, then as partners, teams, and organizations, and finally extending to their constituents and society. As a result of this process, they developed six abilities at each of those levels—leadership, trust, innovation, execution, scalability, and sustainability.

The group used tools you’re likely familiar with: individual interviews and causal maps of diverse stakeholder worldviews; conversation around key themes using dyads, triads, and small groups; mission building (insisting on positive, measurable, time-specific goals) to ensure alignment; behavior over time graphs to assess anticipated performance of that mission over time; causal mapping and validation of the fully integrated system as a whole; systems analyses (including archetype analyses, trends analyses, cross-impact matrix analyses, and stakeholder assessment matrices); group-as-whole meetings for inclusion, engagement, deliberation, and decision making; and, finally, organizational and community dialogue and networking about the process and results.

A Deeper Dive

Now for a deeper dive into how the group accomplished its goals, here’s a more or less chronological flow with a bit of detail to give you a feel for what we did to build capacity at the individual, partner, group, organizational, constituent, and societal levels. (For more on this process, you can download the article “Impossible” at www.innatestrategies.com.)

Individual Leadership. The first thing we needed to know was what the leaders in this system really cared about as human beings, regardless of the stated goal of their organizations. What caused them to devote themselves to their work? What did they envision for whom—their children, students, grandparents, indigenous peoples —or for what—the forests, rivers, lakes, fields, wildlife? We set aside the stated goal of “eliminating poverty” and in one-on-one interviews asked participants what they were committed to in measurable, time-specific terms.

From these kinds of questions came rich, compassionate, human stories at every level and in every sector of Guatemala. Then we asked the leaders to tell us their success stories about how they had done something similar in the past, had seen it done, or planned to do it, that is, to give us their mental models of how the process would unfold. We applied principles from systems thinking and system dynamics to help them flesh out their thinking, get clearer about their leadership role, and consider how they really can and will cause the change they believe is needed.

We reflected this information back to participants in the form of simple causal diagrams that captured their stories, their goals, and all of the parts and interactions. The diagrams clarified their thinking at a higher level and added value to their ability to perceive, think, and act as leaders. As a result of the process, we came to know them, care about them, and even add value to them. And through the work, they came to trust us and the process in which they were about to engage. For an example, see “Fito’s Map.”

FITO'S MAP

The facilitator’s created simple causal diagrams that captured participants’ stories, their goals, and all of the parts and interactions.

One-to-OneTrust. Then, we shared the participants’ stories with the group, either in words or through the maps. People emerged with a new level of understanding, respect, and even appreciation for their perceived “adversaries” in the system. When one set of leaders could see and understand what other leaders cared about and were committed to, how thoughtful and rigorous they were about achieving their goals, and how competent they had been in other situations, their unquestioned assumptions, beliefs, and attitudes shifted almost immediately. A new level of trust emerged and, with it, a new level of conversation. These changes stuck over the long run. Today, the leaders are attending one another’s meetings, engaged in one another’s networks, and sharing information, ideas, and solutions.

Group Innovation. Unfortunately, we still had a problem. We had entered the system through the portal of “eliminating poverty.” That’s a negative goal, and negative goals don’t work very well, because they don’t clarify what people truly want or are trying to create (see Robert Fritz’s Path of Least Resistance, Ballantine, 1989). It’s hard to visualize a negative goal (try it!). So, working from the foundation of trust and clarified understanding that had been created, we identified a small subset of themes and created subgroups (we adapted this practice fromYvonne Agazarian’s work on the interplay between individual, subgroup, and group-as-a-whole dynamics; see Systems-Centered Group Therapy, Guilford, 1997). Subgroups are critical for building collaborative capacity because they bridge the gap between individual conversations and full-group conversations, enabling those who think they are already aligned to first discover, as Agazarian would say, “the differences among the apparently similar” and, then and only then, “the similarities among the apparently different.”

For example, when we brought together the subgroup focused on the elimination of poverty, the members all assumed that it would be the “same old” conversation—but it wasn’t. We quickly discovered that we couldn’t even agree on what poverty was (for example, some people without shoes and living on the land were quite happy and didn’t consider themselves poor even when others did). As differences within their apparently similar views emerged, the participants debated vigorously, trying to resolve their diverse points of view. It wasn’t until they began to offer up positive goals, however, that their conversations began to converge. Subgroup members quickly came to the realization that what they really cared about was “economic self-determination”; that is, they couldn’t guarantee that an individual wouldn’t deliberately choose to be “poor,” but they could build a society that would enable the individual to have a choice. This conversation was incredibly deep, surfacing and integrating universal concepts of liberty, equality, and solidarity.

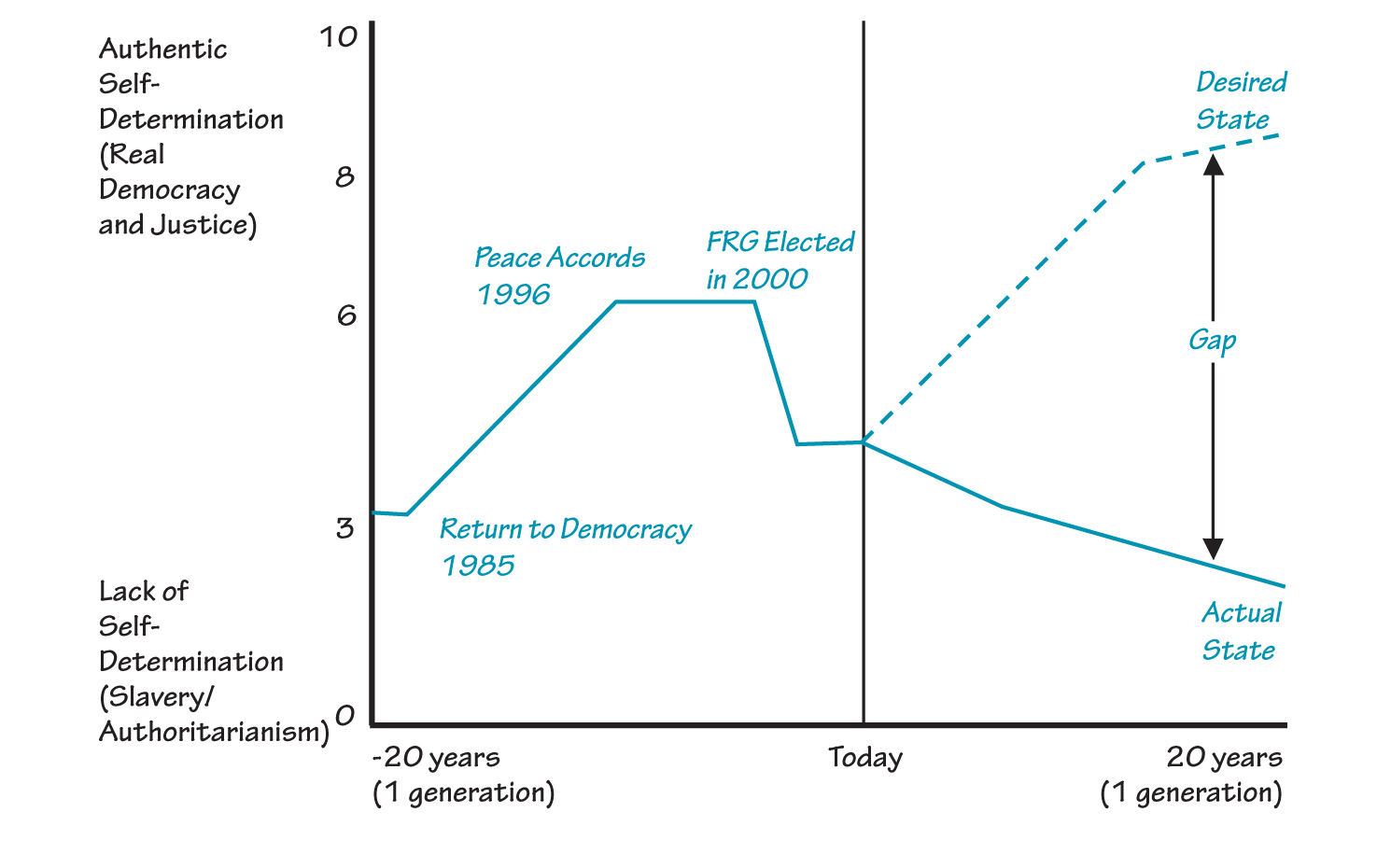

Once this goal had been identified, the group assessed past trends using a behavior over time graph. As a result of the meaningful conversations that led up to the goal setting, what emerged next was a rich, rigorous exchange of information. Individuals with responsibilities and expertise from various parts of the system swapped data back and forth, reshaping their perspectives about the behavior of Guatemalan society relative to this issue over time.

The group came to a sobering conclusion (see “Ability to Self Determine”): That if the downward trend of economic self-determination did not correct itself, Guatemalan society risked a resurgence of the violence that had swept the country prior to the civil war in the early 1960s. This was a somber moment for the group, one that renewed their sense of urgency. They all knew that they couldn’t let that worst-case scenario happen. So, they debated what had to happen by when in order to ensure that the goal of improving economic self-determination could be achieved. The conversation was short and direct: We must immediately reverse the trend, progressing steadily to a reasonably high level of democracy and real justice over the next 10 years.

ABILITY TO SELF-DETERMINE

Using a behavior over time graph, the group came to a sobering conclusion: That if the downward trend of economic self-determination did not correct itself, Guatemalan society risked a resurgence of the violence that had swept the country prior to the civil war in the early 1960s.

The emotional and intellectual energy from this conversation was palpable in the room. Even today, whenever we sense that the process is lagging, all we have to do is flash the group’s graph on the wall again, reawakening their original realization. We anchored and expanded participants’ ability to innovate by having them pair up and develop practices to ensure that they actively internalized both possibilities—the pessimist’s downward trend and the idealist’s upward one—as the dynamic from which creative energy will emerge.

Organizational Execution. The compelling nature of the situation became clearly visible as an unambiguous, uncompromised collective understanding and agreement. But the leaders couldn’t yet see, understand, or agree on why and how economic selfdetermination was continuing to fall, despite their best efforts. To make the roots of these trends visible, we had to take the individual perspectives (the causal maps) of each of the diverse stakeholders and integrate them into a single, inclusive worldview—their own systems map of Guatemalan society.

This expanded perspective made it clear why and how poverty endured, conflict continued, and adversaries couldn’t come to agreement via traditional means. Their system—this “blind, amoral beast” with a lot of momentum —simply reacted “unthinkingly” to inputs to its structure. The conflict wasn’t personal (though it felt that way), but structural. This was a significant breakthrough, enabling the leaders to see and understand how they and people they had come to respect through this process somehow generated results that caused harm to others.

What was most significant about this new, more inclusive, and more rigorous perspective was that the participants began to see how to act in the system and how to effect the changes they all believed were necessary. Aided by the analyses we mentioned before (archetypes, trends, matrices, and so on), they extracted a handful of variables from the model that, if they rigorously and systematically changed, could begin to the shift the system. When coupled with group members’ learnings from the larger map, this understanding and agreement about the need to source each of their projects in the identity of their constituents—those they were most seeking to support—became the basis for robust organizational action.

Scalability. Next came the process of deciding where to start this “movement,” how to spread it, and how to enable it to self-direct and then selfsustain. For CARE Guatemala, it started with the group’s appreciation of the system as a whole and the actors in it. The organization hosted a series of presentations of their systemic map, inviting other stakeholders to critique their insights. What resulted, even with former foes, were profound conversations whose passionate energies were bounded and channeled by the rigor of the societal systems map. Through these discussions, the participants experienced one another as thoughtful, committed, caring, and creative individuals struggling to resolve complex problems. Through the larger map and analysis, they found clarity about how to shift their shared system, not with another symptomatic solution, but at the root-cause level.

Sustainability. The final hurdle/ opportunity to overcome was to ensure the sustainability of the process. Sustainability is a function of the “ecosystem,” whether a biological, social, or environmental ecosystem. In Guatemala, the ecosystem of most immediate concern was the sociopolitical one. Avoiding “extinction” in such an ecosystem meant understanding the commitments, concerns, and circumstances of the major actors. While much of this knowledge emerged naturally along the way, the group took the time to document and then validate it. Doing so enabled members to (1) enter into relationship with critical stakeholders in the larger system and (2) anticipate, adapt, and avoid solutions that would not survive in the ecosystem over time.

This whole process—from individual relationships to ecosystem sustainability—reflected in “Authentic Stakeholder Collaboration.”

From Insights to Practice

In addition to their newly established, ongoing dialogue and work with members of the Guatemalan government, other NGOs, and local constituencies, CARE International is working with 12 partnering NGOs to put these insights into practice. This collaboration is working with 28,000 people in 47 communities in the Cuilco Coatan watershed in western Guatemala, helping them rebuild their lives in the wake of the devastation of Hurricane Stan. Others in CARE Central America are seeking to introduce the process into their work as well.

Something meaningful and useful became possible when these leaders in Guatemala successfully integrated the best of what it means to be human within their work, their relationships, and themselves. They internalized both the intellectual rigor of systems thinking and system dynamics along with the emotional rigor that comes from truly engaging, understanding, and empathizing with one another. In the process, they collectively shifted their perspectives, bringing themselves into greater alignment with their shared reality, and began to act in ways that benefited the whole. What began as something none of them believed was possible has become a new way of perceiving, thinking, and acting in their efforts to cause deep, lasting impact for those they most care about.

R. Scott Spann, MPA, is founder of Innate Strategies, where he works to create deep, lasting impact in business and in society (scott@innatestrategies.com). He integrates leading-edge learnings from business, psychology, system dynamics, and life sciences to solve intractable business and social problems.

James L. Ritchie-Dunham is president of the Institute for Strategic Clarity, an associate at Harvard University, and a managing partner of Growing Edge Partners (jimrd@instituteforstrategicclarity.org). His work explores the emerging agreements that guide human interactions and how humans work with these agreements.

For other papers, books, and presentations on this work and process, go to the Institute for Strategic Clarity library (www.instituteforstrategicclarity.org/research.htm).