As a child of the 1960s, I, like so many of my peers, felt antagonistic toward the world of business. Then in 1979 I became an entrepreneur in a “New Age” business, and the benefits of capitalism became clear. In fact, I still believe that business can be an outstanding discipline for both personal growth and social innovation. The fall of Communism augers even better for capitalism’s future, or does it?

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal (“Das Capital,” November 25, 1991) reviews Karl Marx’s work and concludes that his criticisms of capitalism remain largely valid more than 100 years after they were written. Business Week notes that the rich got richer in the U.S. in the past decade and the poor got poorer (“The Rich are Richer — and America May Be the Poorer,” November 18, 1991). The new UN Secretary General and others have observed that, while the war between East and West is over, the tensions between the wealthy North and poor South have just begun to heat up.

Economic Success to the Successful

What structure underlies the historic and continued tendency for the rich to get richer and the poor to get poorer? And what can be done to change the structure?

Limits to A's Growth?

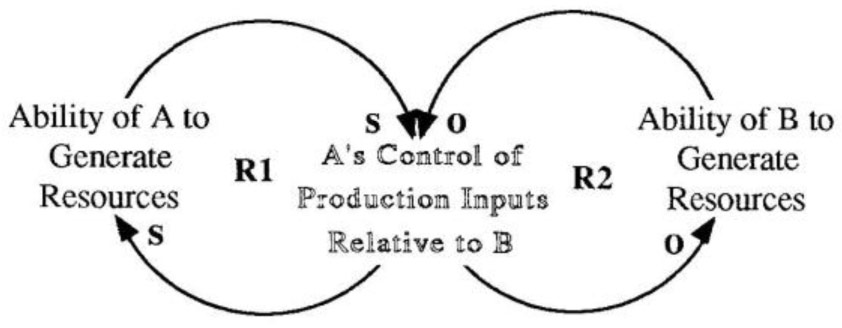

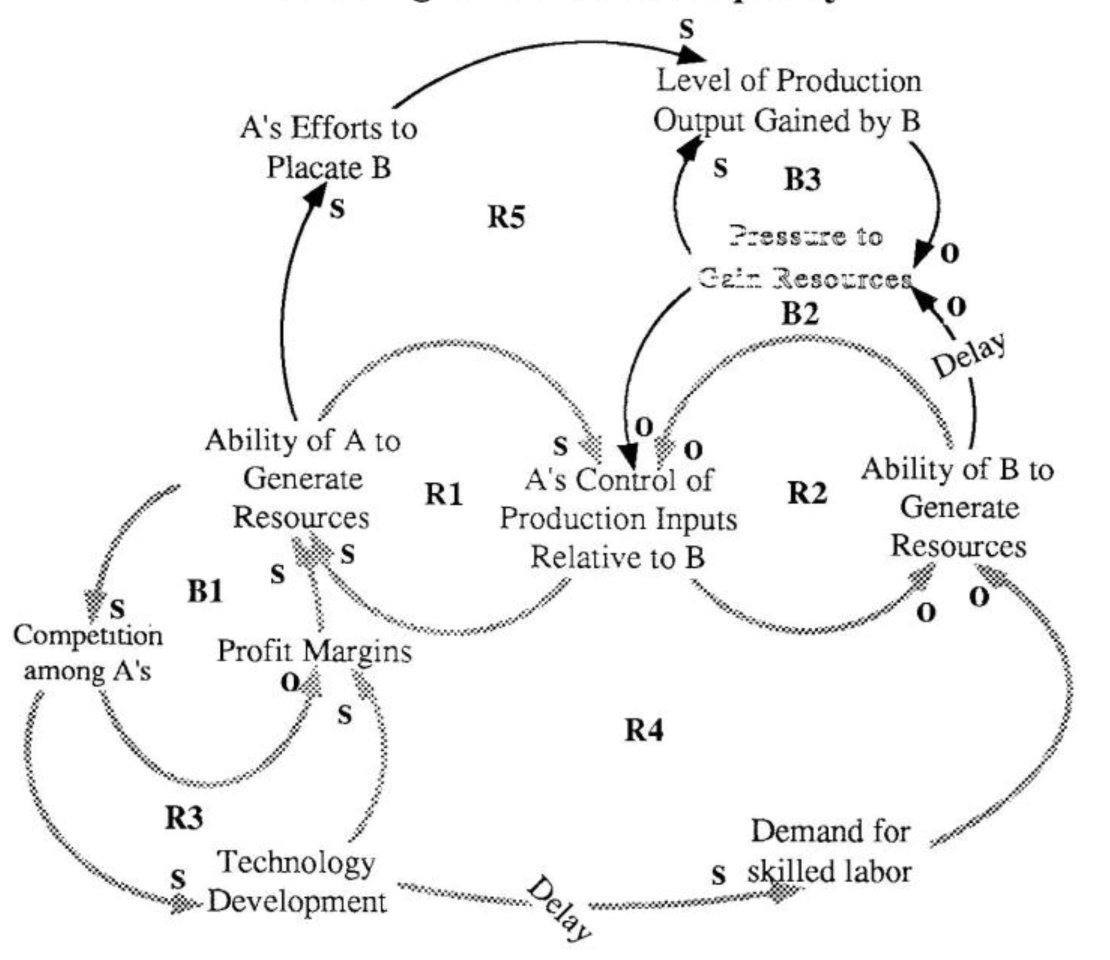

A causal loop diagram can go a long way toward explaining what is happening and suggesting what might be done. The first set of loops, RI and R2, is the classic story of “Success to the Successful” (see “Economic Success to the Successful” diagram). The critical variable is A’s (the rich’s) control of production inputs — resources that include people, capital, raw materials, etc. — relative to B (the poor). As Marx observed, the greater A’s access to the factors governing production, the greater their ability to generate still more resources and thereby control even more production inputs. Poor people are correspondingly able to control less and less of the world’s resources.

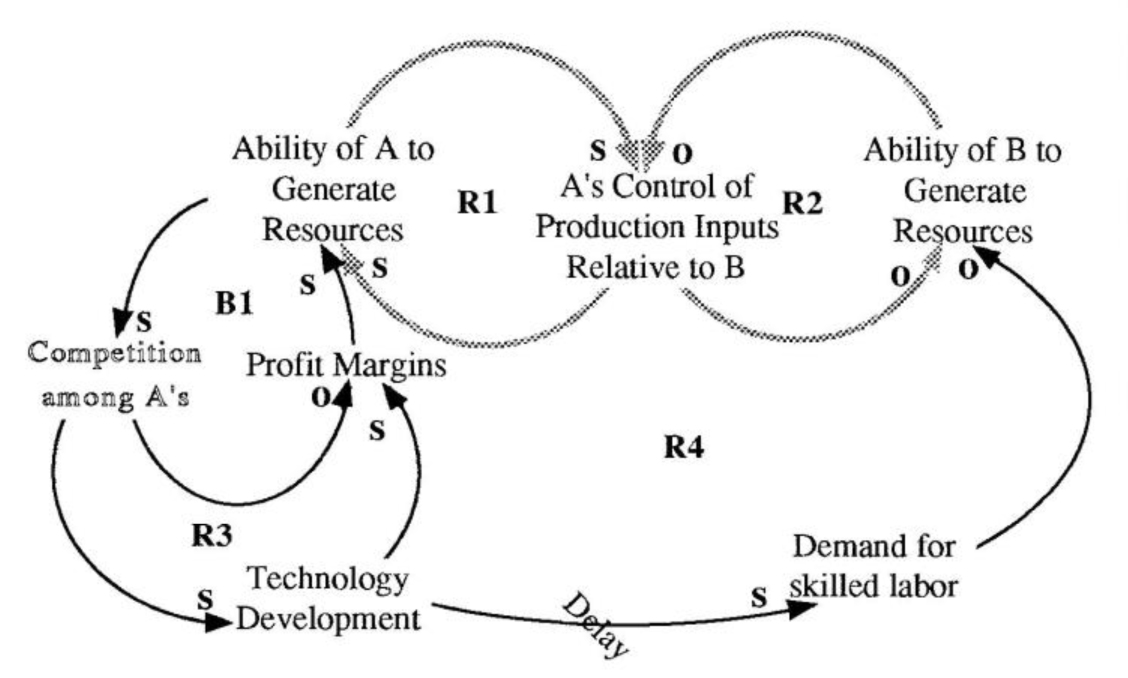

Marx believed that competition among the rich would eventually lower profit margins and temper the ability of the rich to continue to increase their ownership of production inputs, outlining a “Limits to Growth” structure (loops RI & B1 in the “Limits to A’s Growth?” diagram). However, he failed to anticipate the incredible pace of technological development, which has not only kept profit margins high despite competition (loop R3), but also gradually increased the demand for skilled labor, thereby further reducing the ability of the poor to benefit from capitalism’s surging growth (loop R4).

Shifting the Burden of Equality

Inevitably, the declining fortunes of the poor have led them to increase their pressure on the rich to receive more resources (loop B2 in the “Shifting the Burden of Equality” diagram). The first half of the twentieth century saw the development of unions to this end. More recently, violent guerrilla movements such as the Shining Path in Peru have taken their place. The response by the rich to this pressure has generally been to placate the poor by sharing more of the outputs of production, for example through welfare, social services programs, and more acceptable labor contracts. This temporarily lowers the poor’s pressure to achieve equity (loop B3), while simultaneously enabling the rich to maintain control over the factors that k govern production (loop R5).

Together, these loops constitute another classic story, “Shifting the Burden” (loops B2, B3, and R5), whereby society colludes in the symptomatic response for giving the poor more outputs without ever addressing the fundamental inequity of inputs.

Unalterable environmental degradation, caused by an unquestioned commitment to economic growth as an end in itself, may prove to be the ultimate limit on this tendency for the rich to get richer and the poor to get poorer. Before we get that far, we might do well to question what happens to the quality of everyone’s lives when some people gain so much at others’ expense. The model points to the need to redistribute the inputs for production, such as land and capital, not just production’s outputs.

Moreover, as we have learned from the Communist experience, redistribution of resources through centralized public ownership does not work because it reduces people’s motivation to produce. Distributing control over the factors of production, while sharing in the management of common resources such as air and water, is necessary if we are ever going to create a world that works for everyone—and anyone.

Peter Stroh is a senior consultant with the Corporate Organization Consulting Group at Digital Equipment Corporation. Prior to joining Digital, he was a co-founder and senior partner of Innovation Associates (Framingham, MA). He teaches systems thinking for both Digital and Innovation Associates.