If the decade of the ’80s can be characterized as the great boom years of quality awareness in America, the ’90s are beginning to look like a hangover after the big party. After several years and millions of dollars, a large number of companies are sobering up to the fact that their quality efforts are not amounting to much in terms of tangible results.

A study by Arthur D. Little, which surveyed over 500 American companies, revealed that only a third of them felt that their Total Quality Management (TQM) efforts produced any competitive impact. According to Graham Sharman, an expert on quality with McKinsey in Amsterdam, two-thirds of quality programs that have been in place in western firms for mom than two years “simply grind to a halt because of their failure to produce the hoped-for results.” (“The Cracks in Quality, The Economist, April 18, 1992.)

What Went Wrong?

If TQM has been responsible for giving Japanese firms their competitive edge, why is it not producing results for the majority of Western firms? That’s a question many managers are confronted with today, as Total Quality Management efforts at their companies falter. “The majority of quality efforts fizzle out early, or give some improvements but never fulfill their initial promise,” Boston Consulting Group Vice President Thomas M. Hout was quoted in Business Week (“Where Did They Go Wrong?”, October 25, 1991). The TQM movement — viewed as the savior of Western industry when it was introduced in the 1980s — is losing momentum in the U.S. as many companies become disillusioned by the lack of significant progress.

That’s not to say that companies aren’t seeing any benefit from using TQM methods. Companies that have made TQM work for them have gained an edge of up to 100 on every sales dollar, according to A.V. Feigenbaum of General Systems Co. in Pittsfield, Mass.

Companies such as Motorola, Xerox, Coming, Ford, and others have benefited greatly from implementing their own quality programs. But at the same time, the number of companies reporting problems with TQM has also risen.

The problem is not that TQM methods don’t work, but that most Western companies do not fully recognize what it takes to implement the total package and sustain the effort. Many do not go much beyond implementing the statistical-based tools on the production floor. Although such tools can help pinpoint problems in a machine or a particular process and bring them under control, they do not address the larger organizational issues that need to be overcome. In fact, Dr. Edwards Deming, considered by many to be the father of the Japanese quality movement, estimates that statistics-based tools address approximately 2% of the problem. The other 98% has to do with management and systems which govern an organization’s policies and often determine its behavior.

Limits to Success

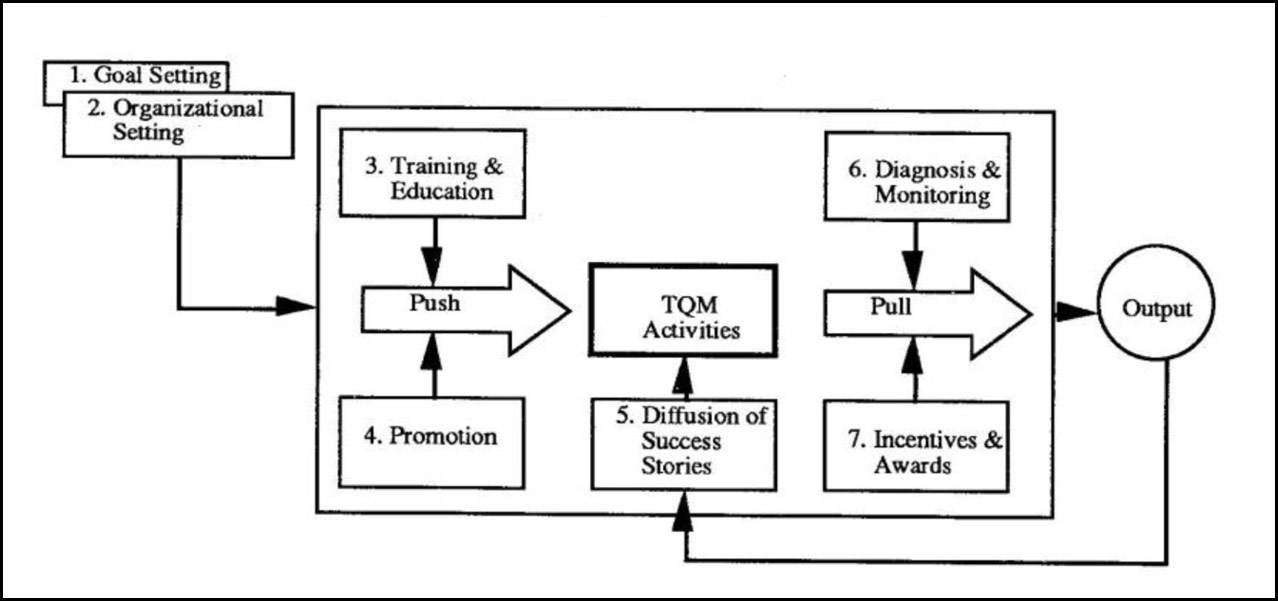

From a systemic perspective, the TQM implementation slowdowns and failures appear to be a classic case of the “Limits to Success” archetype (covered in Toolbox, December 1990, “Limits to Growth: When the ‘Best of Times’ Becomes the ‘Worst of Times”).

In a Limits to Success archetype, a growing action (e.g., marketing) drives a performance or activity (customer orders), forming a reinforcing cycle of growth. When growth slows down due to some balancing force (delivery delay or market saturation), the tendency is to push harder on the original growing action that supported the growth in the first place, rather than to try to understand the sources of the balancing forces. In the long run, this leads to diminishing returns from the reinforcing loops and increasing resistance from the balancing loops.

Most implementation plans tend to place their emphasis on managing the reinforcing loops. The “Typical TQM Implementation Model” shown below illustrates that implementation plans usually emphasize activities that will help drive the growth of TQM activities. An implicit assumption is the expectation that if one does all the things identified in the model to drive the reinforcing loops, the implementation process will be self-sustaining and growing. Evidence suggests otherwise.

Making Sense of Implementation Failures

Many reasons have been given for the failure of quality efforts to live up to their expectations. In some cases, the lack of top management commitment is cited as the problem; in other cases, it’s the resistance of front line workers and/or middle managers. Some have complained that too much focus on the process and not enough on the customer has created quality programs that are overly large and bureaucratic. Others have pointed to an overreliance on outside training courses as the simple quality “fix.”

Although each of the reasons are valid in certain cases, it is difficult to draw any general principles from them which will help one learn from the experience of others. However, many of the failures share the same basic underlying dynamics. We can begin to identify those structures by mapping the experience of other companies who have had TQM “false starts” using systems archetypes as a diagnostic tool. A study conducted by Jim Brown and Scott Tse at the MIT Sloan School of Management explored how systems archetypes can map the experience of individual companies into a common framework that can help other companies identify leverage points for their own implementations.

Typical TQM Implementation Model

The study was conducted with two companies, both of whom had well-defined total quality implementation “false starts.” Through a series of interviews, key players at each of the companies were asked to outline their TQM implementation experience. Using systems archetypes, the interviews were then translated into systemic stories that captured the dynamics of each company’s experience. A look at these two companies can shed some systemic insight into why TQM implementation programs fail — and how future programs can avoid the same pitfalls.

A Tale of Two “False-Starts”

The first company, an integrated circuit producer, embarked on its total quality program in 1984. The company’s false start involved efforts to improve on-time delivery performance at the semiconductor division. Due to the fast-paced nature of their clients’ business, minimizing delivery intervals and meeting promised delivery dates were important for the company to retain its market leadership.

When it was introduced, the process improvement program was well-received by upper management. Quality improvement results were the first item on the agenda at quarterly senior management meetings. A scorecard was used to rank divisions by their results and put pressure on non-performers to “get with the program.” Over time, pressure from being in the “spotlight” and the word-of-mouth effect led to adoption of TQM among all the divisions, with noticeable results. On-time delivery performance increased from 60% in 1986 to 97% in 1990.

In 1990, however, the company experienced some severe pressures. The acquisition of another company resulted in organizational changes, while a downturn in the electronics industry produced in a sharp drop in the company’s stock price, leading to threat of a takeover. As senior management rushed to deal with these new challenges, quality improvement programs gained less and less management attention. On-time delivery performance slipped from a high of 97% in 1990 to the low 90’s in mid-1991.

The second company, a leading manufacturer of electronic systems and software, serves component manufacturers. Its “false start” took place in one of its test equipment divisions, which performs final assembly and testing of the company’s equipment. In 1989, the division was suffering a significant market share loss. At the same time, major customers were complaining about poor quality.

Under a directive from corporate headquarters, the divisional manager began a quality improvement program. A Quality Improvement Team (QIT) was set up, and members were sent to the Crosby quality college for training. Commitment to the program varied among the QIT members, however. Some never attended the college. Phone calls and other meetings were given priority over weekly QIT meetings, and action items were accomplished sporadically.

The team finally prepared a Total Quality awareness seminar for division employees. However, follow-up training was never provided, due in part to poor planning and a corporate-wide TQM program that was being launched at the same time. The effort eventually fizzed out and was replaced by the corporate-wide TQM program.

Analyzing the False Starts

Though both stories have their own unique focus, when they are analyzed using systems archetypes, the common underlying structures become evident. In the Brown and Tse study, they identified several archetypes which were common to both companies (also see “Common Implementation Themes” on page 4).

For example, both companies experienced a “Tragedy of the Commons” scenario (see “Tragedy of the Commons: All for One and None for All,” August 1991). In a “Tragedy of the Commons” structure, individuals use a commonly available but limited resource solely on the basis of individual need. At first their efforts are rewarded. Eventually, their returns diminish, prompting them to intensify their actions and leading to further erosion of the resource. At the integrated circuits manufacturer, shipping activities and TQM activities competed for a common resource — workers’ time and attention. In the electronics firm, software development and TQM activities were also adding to the total workload. In both cases, maintaining a careful balance between TQM activities and daily work would be critical in preventing overload, thereby reducing the commitment to the TQM program.

“Limits to Success” is perhaps the most pervasive archetype in both stories. Of the 13 stories identified in the study, 9 were classified as cases of “Limits to Success.” It shows up, for example, in resistance to Total Quality initiatives at the semiconductor company and the lack of training at the electronics company (see “Implementation Limits: Two Examples”). At the semiconductor firm, the adoption of the TQM initiative gradually built up resistance to the program, especially among managers who felt they were being labeled “non-performers” by the poor weekly results posted for their division in the scorecard. A continued lack of improvements, however, also led to frustration on the part of the managers. Over time, this frustration grew enough that it overwhelmed the initial resistance to the TQM efforts, thereby removing the limit.

Implementation Limits: Two Examples

In the electronics testing division, a lack of training capacity limited TQM improvements. The initial training session generated much interest throughout the division. After some initial success in applying the tools and theory of TQM, however, workers found that further improvements were limited by a lack of ongoing TQM training. Eventually, the TQM initiative died out, and was replaced by the corporate-wide TQM program.

Both companies also encountered other limits in their TQM efforts: a lack of trained TQM facilitators; a resistance to TQM by employees who feared losing their jobs; a need for additional capital investments; and time needed to implement TQM activities.

Lessons for other TQM Efforts

Once a Total Quality program fails, the temptation is to give up on TQM entirely. However, the “Limits to Success” archetype suggests that the problem may not be with the methodology itself, but the way it is implemented. Without an understanding of the underlying dynamics shaping any TQM program, failures can too often be attributed to individual actors or specific circumstances. Systems archetypes can help to make sense of other companies’ experience as well as one’s own by identifying common structures at work. They can do more than just categorize past experiences; they can help guide future action by mapping out potential pitfalls and leverage points. With “Limits to Success,” for example, the lesson is clear: even if you gun the engine, you won’t get very far if you don’t take your foot off the brake.

Further reading: Jim Brown and Scott S.F. Tse, “A System Dynamics Analysis of Total Quality Management Implementation False Starts,” Unpublished master’ s thesis, MIT Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, MA; Daniel H. Kim and Gary Burchill, “Systems Archetypes as a Diagnostic Tool: A Field-based Study of TQM Implementations,” Working paper D-4289, MIT Organizational Learning Center, Cambridge, MA.