Introducing learning organization principles to a company is difficult and fraught with uncertainty. How do you lead without taking the reins? How do you protect the foundation of the company while encouraging risk? How do you assess performance without focusing on what’s wrong? These were the issues we faced as we tried to enact a widespread cultural change in our company.

At Biach Industries, a “command-and-control” culture had developed out of a drive for growth coupled with a lack of management experience. Aftershocks from an extremely autocratic general manager raised the awareness that people need to be treated with dignity and encouraged to express their creative talents. This shift in perspective — along with the arrival of a consultant who had successfully experimented with the principles of the learning organization — attracted us to explore shared vision, personal mastery, and the related learning disciplines.

Our approach involved a shift from pathology to vision. Rather than correcting problems of the past, we are focusing on choosing and manifesting a future. The difficulty, of course, is that the systemic barriers to creating change have roots in both corporate and personal history. These limiting beliefs about what we can create in our lives are influenced by the many systems in which we live and work, including our culture. The current fear of unemployment, for example, affects our perception and tolerance for risk, creating barriers that we, as managers, have only marginal leverage to alter. As a result, our biggest struggles at Biach have been in areas that directly challenge how our culture has taught people to work, think, and perceive.

Blades Culture

Biach Industries is a small (40-person) manufacturing company that was founded by John L. Biach in 1955 to supply custom-designed tooling to the growing petrochemical and nuclear power industries. In the 1970s, with OPEC, Three-Mile Island, and the founder’s death, the company was left with a vacuum in both talent and market — a hole that has taken 15 years to begin to fill.

Our history at Biach has created an organizational culture that challenges our attempts to create a learning organization. For example, one family member who ran the company from 1973 to 1991 lacked confidence and was afraid to make a mistake. Thus the company inherited a structural aversion to risk and a paralyzing decision-making process.

There was also a deep sense of entitlement. With few competitors and a good stream of spare parts orders, the steady flow of business produced a false sense of security. The company always muddled through, regardless of how well any one individual contributed. Thus, poor and mediocre performance was largely tolerated — no one had ever been fired, and employee performance was not adequately assessed for fear of erroneous judgment. With no correlation between performance and corporate survival, people believed good performance had no real impact on the company and therefore was of no real value.

Planting the Seeds of Transformation

To attempt to transform the company culture, our corporate rebirth needed to focus on two areas: structural changes, such as policies, procedures, and values; and transformational changes, which attend to individuals’ personal awakening and transformation.

Structural changes require raising awareness of the structures in which we live and work and their influence on our behavior. For example, suppose a part is manufactured incorrectly due to a confusing dimension in a drawing. Does the fault lie with the machinist, the draftsman, sales (for creating unnecessary time pressure), or a corporate belief that good drafting is easy and not worth paying attention to?

The company’s structure is also being redrawn to facilitate implementation of employee choices. Supervision, for example, is becoming a coaching and support activity rather than a controlling one. The employees now get a monthly bonus based on profits, and the books are open to everyone. This openness and sharing has fostered a deeper trust in management and has eased fears that people are being manipulated by the widespread changes that are occurring.

We have found, however, that people depend on structures for security and therefore tend to sabotage efforts to change them. In order to create lasting improvements, we need to develop a self-sustaining support environment independent of our changing structure. We are therefore focusing on personal transformation, personal mastery, and employee workshops that foster a sense of shared visions.

Transformational changes are more difficult to facilitate than structural ones because they are tied to the sociocultural system and are related to our values in religion, government, law enforcement, education, parenting, family, and business. Essentially, for Biach, transformational changes involve neutralizing the influence of our culture that keeps people from believing they can choose their own future.

Developing Shared Visions

Our work in transformational change has led us to develop “creative tension workshops.” These intense learning experiences involve exercises exploring the discipline of personal mastery. We have conducted two of these workshops, enabling each employee in the company to participate. In preparation for these sessions, individuals answered some interesting questions—such as “Who is your personal hero?” — that prompted them to begin thinking about their vision.

In the workshops, we spent a great deal of time helping the groups understand what visions are about and helping individuals realize that they — and the company — arc entitled to have their own vision. By compiling the results of the questionnaire and presenting it to the group, we tried to demonstrate that many of their core needs and aspirations were shared by their peers. Collectively they discovered that there was a strong organization-wide orientation toward spiritual and humanitarian achievement in the company.

Creative Tension

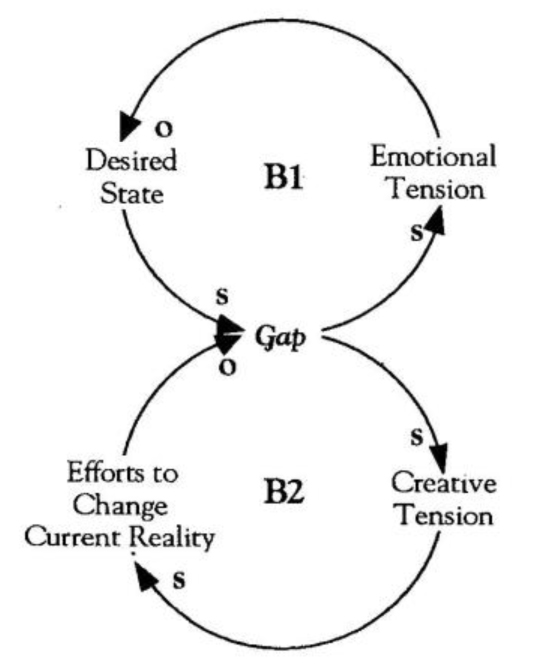

A gap between vision and current reality creates both emotional tension and creative tension. Lowering as vision (B1) will ease the emotional tension, while taking steps to achieve our vision will reduce the creative tension (B2).

After we spent some time in the workshops exploring our personal and organizational visions, we took a look at our current situation in order to build some creative tension. This natural tension occurs when we simultaneously hold in our minds a picture or vision of where we want to be and face the truth about current reality. In order to create a picture of our current reality in the company, we broke into groups to share and gain consensus on the character of various segments of the company.

In the first workshop, we took this one step further and attempted to resolve the creative tension by developing a scenario that would bring our current reality in line with our vision. Given the scope of the workshop, however, we found this was too aggressive a goal. In the second workshop, we revised this section of the program and prepared a possible scenario for the group to consider. This was not successful, either. While our intent was to position the scenario as one of many possibilities, it was received as “the” business plan for the company. We learned that vision is a complex and often elusive concept. On a more subtle level, we discovered that for many people imagining future desires is frightening; the image of getting what you want seems contrary to our prevailing cultural belief system.

Outcomes

As a result of these workshops, we are beginning to establish corporate and personal visions, and understand how the two relate. Some people have also begun to identify larger visions in their work that extend beyond the traditional pay-for-work employment contract.

For example, one managing director’s vision consisted of establishing residence in a less-stressful part of the world. He had always had a fascination for Ireland, and for the company, Ireland offered a convenient, low-cost business presence in Europe. This dual corporate/personal vision is currently being enacted, and is expected to become a reality in early 1994.

Changes in our employee assessment program are another outcome of our visioning work. Rather than focusing on employee deficiencies, the program seeks ways to gain better alignment between individual and corporate achievement. We solicit the personal expectations of the individual and then explore what the company might do to facilitate, in a strategic and tactical way, the realization of those goals. This has given everyone at Biach a glimpse into the many possibilities for personal and organizational transformation that can exist when there is a creative and honest relationship between the individual and the company.

The most important learning we have experienced is the importance of trust among employees, executives, and owners. Trust enables people to transcend their limiting beliefs and take risks. And it develops slowly, regardless of your actions or the amount of good will you possess.

We have found that we also need to be patient in working toward our visions. To resolve creative tension, people either lower their vision to meet their current reality or they take steps to change their current reality to match their vision (see “Creative Tension”). We have found that typically people lower their vision so they do not have to experience the emotional stress that often occurs when living with a gap between vision and current reality. As leaders, we need to help people stay focused on their visions. Our own commitment to our personal visions offers the best proof that the future can become a product of our dreams and not merely a reaffirmation of the status quo.

William L. Biach and Mike Nash are two of three managing directors of Biach Industries. Bill’s background includes research in mathematics and physics, mechanical design, performing arts, futures research, and computer science. Mike stoned in chemical engineering, received em MBA at Harvard, and held senior management and consulting positions in several public and private firms. This story was told in greater detail at the 1993 Systems Thinking in Action Conference and is available on audiotape from Pegasus Communications. Editorial support for this article was provided by Colleen Lannon-Kim.