Recently, the New England Fishery Management Council adopted promising new rules for regulating threatened regional fish stocks. The new rules will over time shift accountability for responsible harvesting from individual fishermen to cooperative groups of fishermen coordinating their activities to balance profit with environmental impact.

A Collapsing Stock

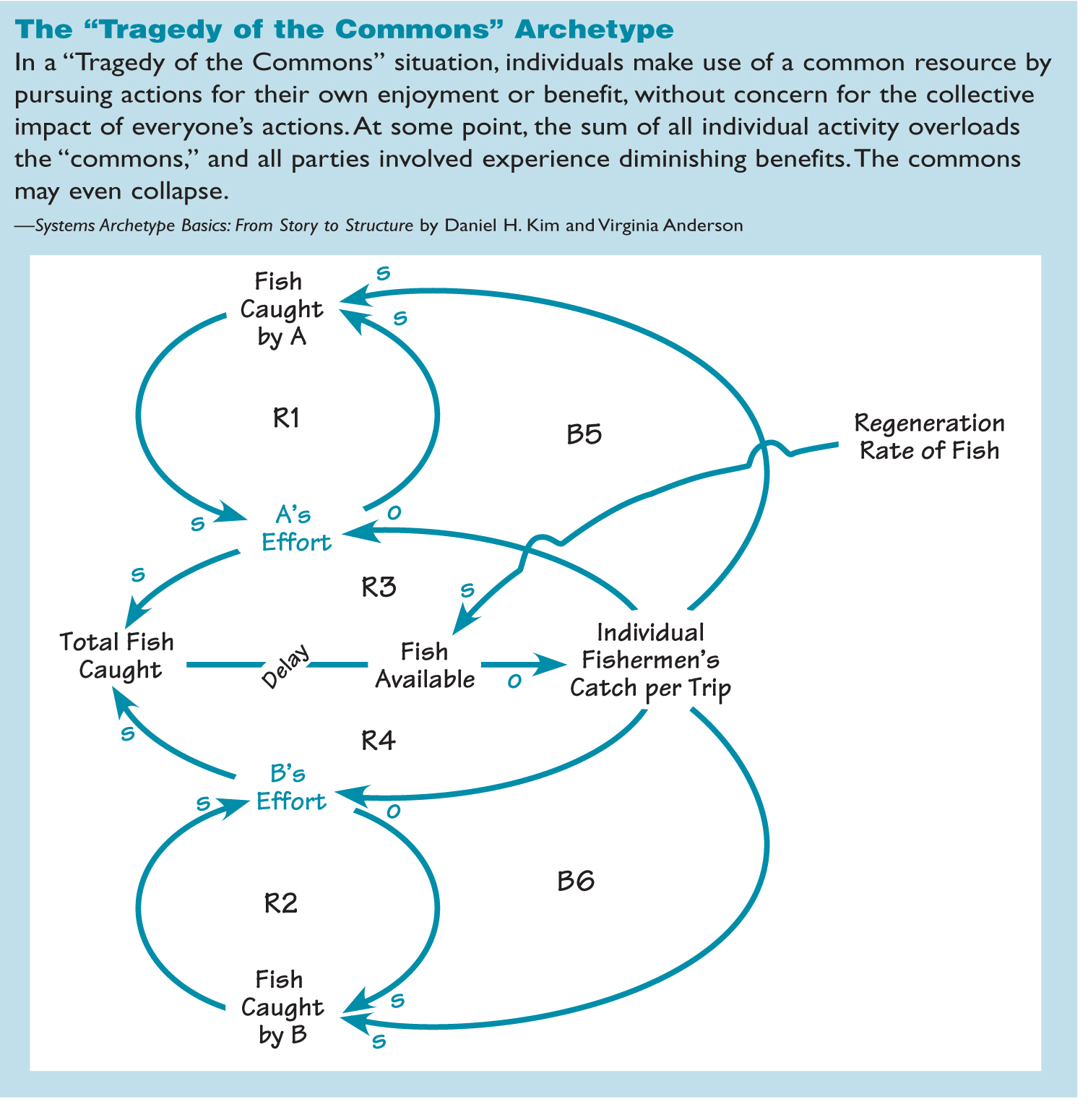

It is only within the last fifty years or so—after generations of benefitting from a seemingly inexhaustible supply of fish off the coast of Cape Cod—that regional fisherman have come face to face with the limits described in the

TEAM TIP

The “Tragedy of the Commons” dynamic can also appear in organizational settings, for example, in the form of the production person or administrative assistant who serves as a resource for several people. Be sure to coordinate demand so as not to burn out this valuable contributor.

“Tragedy of the Commons” systems archetype (see “The ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ Archetype”). Mid-20th century technological improvements in fishing methods and equipment accelerated fishing efficiencies in a way that completely changed the environment. As Robert Johnson and Jon Sutinen note in their recent report, “One Last Chance: The Economic Case for a New Approach to Fisheries Management in New England,”, “Species that provided a historical foundation for economic growth in New England— Atlantic halibut, cod, flounder, and others—have been fished to decline, biological collapse or commercial extinction.”

In 1976, recognizing the dangers both to fish stocks and to the economy, the federal government passed legislation imposing catch restrictions on this iconic fishery, and on others in the U. S. But, there was a fatal flaw in the government’s initial approach to regulation. In his excellent book, Naked Economics, Charles Wheelan cites a BusinessWeek column by Gary Becker, describing the short-sightedness of regulations pertaining to striped bass fishing on Cape Cod:, “At the time [Becker] was writing, the government had imposed an aggregate quota on the quantity of striped bass that could be harvested every season. Mr. Becker wrote, ‘Unfortunately, this is a very poor way to control fishing because it encourages each fishing boat to catch as much as it can early in the season, before other boats bring in enough fish to reach the aggregate quota that applies to all of them.’ Everybody loses: The fishermen get low prices for their fish when they sell into a glut early in the season; then, after the aggregate quota is reached early in the season, consumers are unable to get any striped bass at all.”

Aggregate limits were scrapped in the mid-1990s in favor of complex controls on individual fishing activities— referred to collectively as “days-at-sea” limits. These were no more successful, as Johnson and Sutinen point out: “When vessels only have a limited number of days-at-sea, it creates a perverse incentive to catch fish as quickly as possible during available days. Responsible fishermen who could otherwise take the time to fish in a safe, profitable and ecologically conscientious manner are induced to put aside these goals in an attempt to catch as many fish as possible in the few days they have available. Fishermen are given little incentive to avoid overfished stocks and target healthier populations; in order to reduce pressure on overfished stocks, effort controls become so restrictive that it is no longer possible to harvest an optimal quantity of the few remaining healthy stocks. The result is inefficient, costly, unsafe and more damaging to the environment. As fish stocks and profits decline, perverse incentives only increase.”

Cooperative Management

But, as the recent promising developments would suggest, the situation is not hopeless, and the most sustainable solution may very well come from the people closest to the problem: the fishermen. The latest evolution in stock regulation in New England focuses on cooperative fishery management, in which groups of fishermen—known as “sectors”—are given a renewable privilege to harvest a specific quantity of fish.

The sector approach offers fishermen flexibility around when and where to fish. By sharing, trading, or consolidating catch privileges among sector members, fishermen can reduce their costs and eliminate the practice of throwing back waste fish that they’ve over caught. With the individual days-at-sea limitations eliminated, they will be able to concentrate on increasing the quality and value of the fish they catch without worrying about lost fishing time.

The new rules may not be perfect; some are concerned about fairness, and enforcement mechanisms will have to be carefully monitored. But, these first steps toward a cooperative, community-based management structure seem to offer evidence that New England fishermen are ready to moderate the collective impact of their individual efforts in the interest of sustaining this irreplaceable resource for everyone— and that government agencies are willing to give those closest to the situation the tools to manage it.

Vicky Schubert is marketing director at Pegasus Communications.