A growing awareness that humankind is facing unprecedented challenges is making many of us uneasy. Our unease stems from an increasing sense that humanity’s bill for our impact on the health of the planet is now coming due. Overwhelmed by complexity, we are beginning to question our government and business institutions. We are aware that many are woefully inadequate to shape a future worthy of our descendants. We are at once both fearful and hopeful.

The question that stands before us now is not who can take part in the cultural transformation needed to address these complex problems, but how shall we stand together to do so? Will we simply try to fix the problems we now face with the same mindsets that created them or will we learn to be together in new ways?

Fortunately, every person can participate in and contribute to the creation of a new global ethos of partnership and peace. In fact, we do so each time we choose:

- discernment instead of judgment

- appreciation over criticism

- generosity in place of self-interest

- reconciliation over retaliation

A culture of partnership is one that supports our full humanity and helps us reach our highest human potential. Whether we build this culture depends on the choices we make, from the seemingly insignificant to the most exalted. By understanding our options, we can make wise decisions.

TEAM TIP

Use the principles outlined in this article to determine whether your organization follows a “dominator” or “partnership” model. Explore the implications for teamwork at each end of the spectrum.

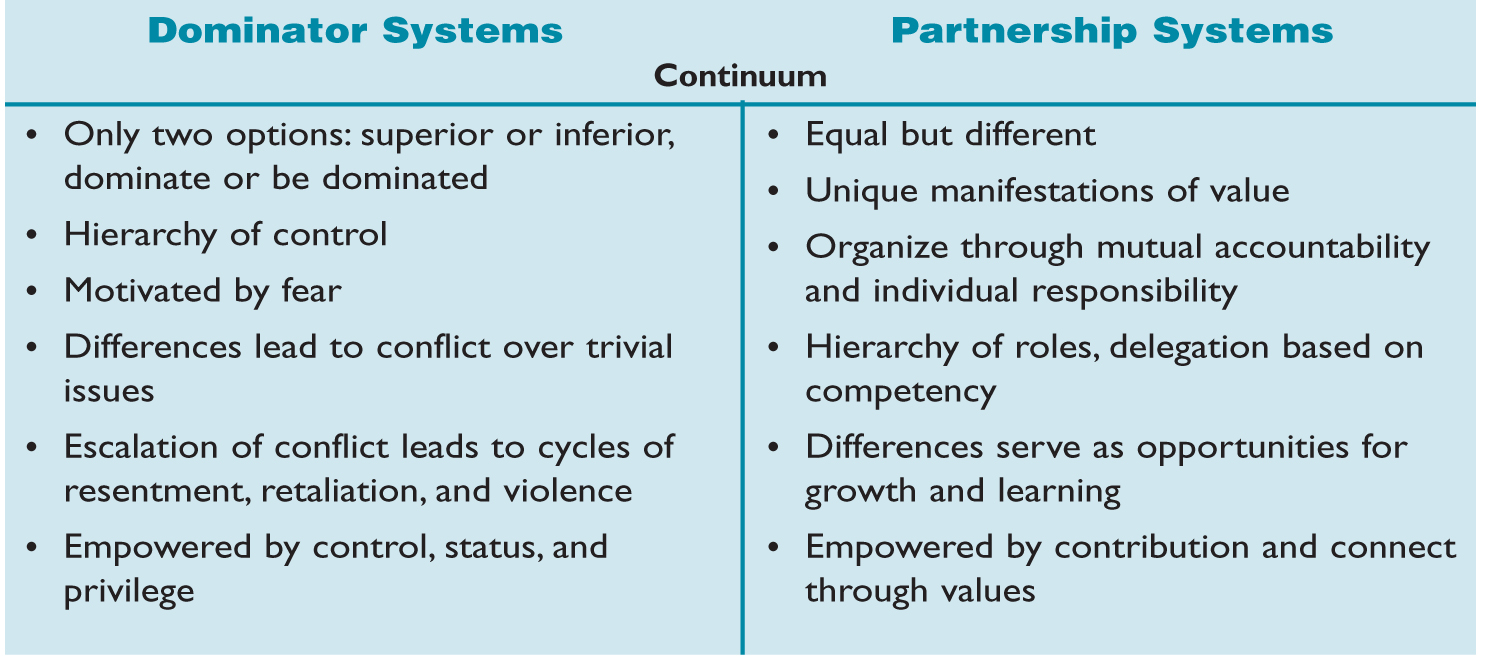

Reframing the Conversation

Through two decades of research, Riane Eisler (one of the authors of this article) found a fundamental difference in how human societies evolved (for a detailed discussion, see The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future, Harper Collins Publishing, 1987). She documented that, from the beginning, some cultures oriented more to what she termed a dominator system and others to a partnership system — and that gender roles and relations are structured very differently in each (see “Dominator-Partnership Continuum” on p. 10). In dominator systems, social ranking begins with our most fundamental human difference—the difference between female and male. The male and what is stereotypically considered masculine is valued over the female and the stereotypically feminine. This foundational ranking of one gender over the other sets in place a pattern of social rankings based on other differences, such as ethnicity, race, religion, and so on.

In partnership systems, societies value both halves of humanity equally and recognize that humans are social animals with a unique wisdom and capacity to work and live together. Here, stereotypically feminine traits and activities such as caring, nonviolence, and caregiving are highly valued — whether they reside in women or men. This orientation profoundly affects the society’s guiding system of values in all institutions, including business, government, and economics. For example, using the lenses of these social categories makes it possible to see that caring for people, starting in childhood, and for the Earth are important in human and environmental terms.

Toward the dominator end of the spectrum, social systems organize relationships at all levels according to a hierarchy of control, status, and privilege. They routinely extend rights and freedoms to those on top and deny them to those on the bottom. Such rankings lead to thinking limited to two dimensions: superior or inferior; dominating or dominated. Since there is no awareness of the partnership alternative, both parties live in fear. Those on top fear loss of power and control while those on the bottom perpetually seek to gain it. This ranking structure then leads to conflicts — sometimes over trivial issues — that escalate, often leading to cycles of violence, resentment, and retaliation. Such conditions do not generally contribute to growth, learning, or peace.

Social systems toward the partnership end of the spectrum are characterized by more egalitarian organizational structures in which both genders are seen as equal yet different, each capable of unique manifestations of value. A hierarchy of roles may exist, but delegation tends to be based on competency, rather than rankings by gender or other arbitrary groupings. Each group is capable of appreciating the unique value of the other. Differences are seen as opportunities for learning, and both individuals and groups organize through mutual accountability and individual responsibility. Empowerment stems from one’s unique contributions, and connections are made at the level of values, rather than by gender, ethnicity, and other social categories.

In her most recent book, The Real Wealth of Nations: Creating a Caring Economics (Berrett-Koehler, 2007), Riane provides extensive evidence of how caring business policies that result from partnership values are actually more profitable than those that stem from dominator values. Economists tell us that building “high-quality human capital” is essential for the postindustrial, knowledge economy. Nations that invest in caring for children are doing just that—while those that do not will dearly pay for this failure.

Learning Conversations

In a global society, we see all shades in the spectrum between dominator and partnership systems. But the necessity to make headway on our intractable challenges requires that we accelerate the movement toward the partnership side of the continuum. A simple way to contribute to designing the future we desire is conversation. Conversation costs nothing but time and can include everyone. Conversations are one of the cornerstones of civic engagement. For millennia, they have served as a means to explore, defend, persuade, connect, and heal. Conversations become the threads of the social fabric of our lives, contributing to communal beliefs, expectations, and judgments about the structures and relationships underlying our families, tribes, communities, institutions, and nations. Conversations are so powerful that in an effort to control their subjects, despots and dictators often limit what topics can be discussed and how or if conversations are allowed.

DOMINATOR-PARTNERSHIP CONTINUUM

The necessity to make headway on our intractable challenges requires that we accelerate the movement toward the partnership side of the continuum.

Modern social science and psychological research has found that the what and how of conversations often lead to defining moments. The what of conversations are the topics we choose to discuss, and the how includes ideas for holding conversations from which we can learn and grow, rather than persuade, coerce, or intimidate. The purpose of holding conversations about our fundamental differences is, therefore, not to blame or judge each other or ourselves. Conversations are held in order to learn what still binds us to the dominator dynamic and to allow us to see each other and our world more clearly.

To understand what divides us, we must look honestly and earnestly at our differences. We must make an effort to understand the other’s point of view and to share our own. The best way to have a powerful conversation about what separates us is to simply listen, become aware of the meaning we may be making for ourselves from what we hear, and recognize that what the other person is saying is true for her or him.

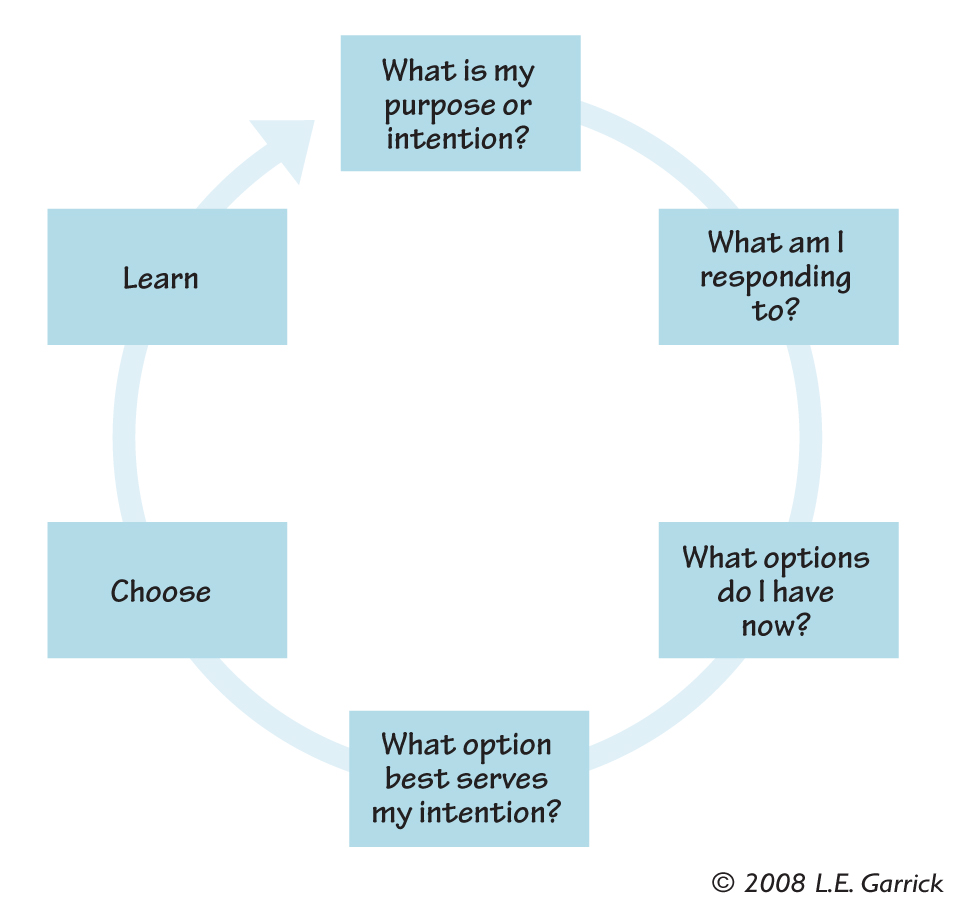

At first, it may be difficult to hold neutral conversations due to the learned meanings we draw from words, phrases, and even tone of voice. Even if you hold your heart for humanity deeply, you are likely to carry some biases based on the tacit meanings that come from your experiences in life related to your own gender. To truly understand the other, you will want to consider what it is like to be in the other’s shoes, to have their beliefs, points of view, and experiences. The “Learning Practice of Leadership” may serve as a helpful reminder for how we can lead ourselves through the controversial waters of gender conversations (see “Learning Practice of Leadership” on p. 11).

Tips for Partnership Conversations

Below are tips for holding partnership conversations and some sample questions to get you started. These tools will be particularly useful in dealing with emotionally charged issues.

- Convene the conversation in circle so that everyone holds an equal position.

- Take time to allow people to get settled and leave their work and other concerns behind. Prepare a question that allows people to get introduced and learn a little about why they have joined this conversation.

- Allow each person to speak when they are ready. There is no need to pressure anyone to talk. People will learn both from listening and speaking.

- Allow each person who wishes to speak adequate time to do so without interruption.

- Select a question to start the gender conversation. Several are included in the bulleted list below.

- As you explore the conversation more deeply, use open questions. Open questions are questions to which there is no “yes” or “no” answer. They are not intended to lead to a specific outcome. Open questions come from a genuine place of curiosity. They often begin with words like “how,”, “what,” “when,” and “why.”

- Be mindful of your intention when asking any question. If you have a judgment behind your question, it will likely show through., “Why” questions are particularly tricky as they sometimes sound accusatory, such as “Why do you believe that?”

- Be transparent by stating your personal experiences in relating a position or asking a question.

- Listen and try to put your judgments aside.

- Resist the temptation to voice either your own affirmation or your disagreement with another person’s point of view. Allow each speaker to be accountable for their own words.

- If you find you are having a strong reaction to someone’s comment, good or bad, make a note for later reflection. Ask yourself, what is creating this reaction?

- In these conversations, it is not important to convince or draw conclusions, but to listen and learn. Have something to write on. Jot down what you notice. And when time allows, journal about what you notice about what you notice. See where a deeper inquiry leads without trying to find the “right answer.”

- When the conversation has concluded, take time to record notes about what you’ve learned.

- Reflect on new questions you may have as result of the conversation and new options for relating with others.

LEARNING PRACTICE OF LEADERSHIP

Examples: Gender Topic Questions

- What is the first memory you recall in which gender played an important role?

- What happened?

- Do you recall any conclusions you may have drawn as a result of this experience?

- Did the experience make you feel more satisfied to be your gender or less? More empowered or less?

- How do people in your church, work, or community express gender equality and gender rankings?

- What evidence do you find that men are more valued than women?

- What evidence do you find that women are more valued than men?

- What do males and females have in common when it comes to personal values?

- What do you believe about the expression of gender in living species that influences your attitudes about gender differences in humans?

- Think of a major historical event in your lifetime. If you were a different gender, how would your interpretation of that event be changed?

- How do the perceptions we hold about gender influence our attitudes toward power and money?

- What would be different if you had been born a different sex?

- How would the sexes have to change to live more closely aligned with the partnership model?

- What would be the impact to government, business, and other social systems?

Not Just a “Women’s Issue”

Exploring the issues that divide us by examining how we are influenced by our experience of gender can be powerful. It may lead to further inquiry to uncover how gender differences impact your family, community, work, and institutional relationships. In turn, these explorations may give rise to questions about how culture and nations impact each other through our policies, markets, and impact on the planet.

Beginning with our most fundamental human difference, the difference between male and female, it is now time to understand deeply how our gender privileges, limitations, and experiences have shaped and continue to influence us, not only as individual women and men but as members of a world that has inherited a system of values that is heavily influenced by dominator valuations.

One of the most interesting, and important, outcomes of open-ended conversations about gender is a new understanding of what it means to be human for both women and men — and that gender is not “just a women’s issue” but is a key issue for whether we move to a more peaceful and equitable world. As more of us talk openly about these matters, we become participants in the cultural transformation from domination to partnership — not only in gender relations but in all relations. We also help create more effective, humane, and sustainable business practices and government policies when we bring these unconscious impediments out into the open.

Note: References to behavior resulting from the ranking and hierarchy of roles in dominator and partnership systems were adapted from the work of Virginia Satir and the Satir Institute of the Pacific.

Riane Eisler is a social scientist, attorney, consultant, and author best known for her bestseller The Chalice and The Blade: Our History, Our Future, now published in 23 languages. Her newest book, The Real Wealth of Nations: Creating a Caring Economics, hailed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu as “a template for the better world we have been so urgently seeking” and by Peter Senge as “desperately needed,” proposes a new paradigm for economic systems. Riane keynotes at conferences worldwide, teaches transformative leadership at the California Institute of Integral Studies, and is president of the Center for Partnership Studies (www.partnershipway.org).

Lucy E. Garrick is an organizational leadership consultant, speaker, artist, and founder of Million Ideas for Peace, a public project designed to help individuals connect their personal and social passions to peacemaking (www.millionideas4peace.com). Lucy consults with corporations, nonprofits, government agencies, and public groups to improve individual and group leadership and performance. She holds a masters degree in Whole Systems Design, is chair of the OSR Alumni Association board of directors, and is principle consultant at NorthShore Consulting Group in Seattle, WA (www.northshoregroup.net).