During these difficult times, nonprofit organizations often provide the backbone to many communities, offering a much-needed safety net for those in need. Behind the public face of each nonprofit sits a board of trustees, providing the support and guidance — and frequently a fair amount of sweat equity — to keep the organization afloat. Although the recession has taken its toll and has forced many nonprofits to close or merge, current figures show that there are still 1,569,572 tax exempt organizations registered with the Internal Revenue Service, with 30,000 new nonprofits registering between January and August 2010 (Source: National Center for Charitable Statistics). Add in publicly elected bodies, and the number of boards in the U. S. alone is staggering.

Given those numbers, it’s not surprising that there is a huge need for governance training, and yet many board members never receive any instruction during their tenure. With resources typically scarce in nonprofits, those serving on boards would prefer to see money invested in programs and services rather than in themselves. New board members usually learn their roles by observing current board members and following their lead. The result can be self-perpetuating cycles of inefficiency and ineffectiveness. In this situation, practicing systems thinking can help.

Governance Roles

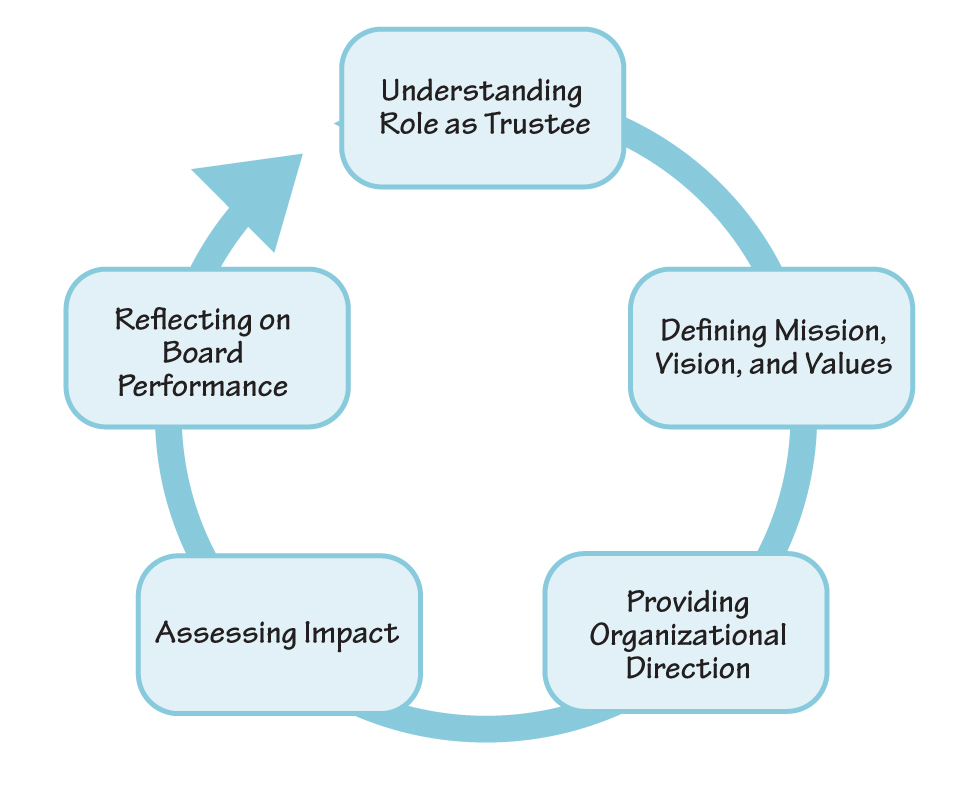

First, however, let’s clarify governance roles and how those roles link together to create a cycle of governance (see “Cycle of Governance” on p. 9). The word “trustee” is often used to refer to a board member, because board members are “entrusted” to make decisions on behalf of those they represent. For a publicly elected board, determining for whom you make decisions is relatively easy (it’s the taxpayers), but for a nonprofit, it can be challenging. Is it the clients? The staff? The funders? The community? All of the above? None of the above? These questions provide board members with a great opportunity to engage in dialogue, because to be successful, the organization must know whom it represents.

TEAM TIP

Leadership teams in other industries would also benefit from developing systems thinking skills before their organizations experience an acute problem.

Once board members clearly understand whom they represent, they can then begin the process of defining the organization’s mission, vision, and values. The mission answers the question, “Why do we exist?” The vision describes what success will look like at a particular point in the future. The values are the organization’s guiding principles, that is, how it wants to act, consistent with the mission, along the path toward achieving the vision. The board defines these three keystones in conjunction with the staff, stakeholders, and community.

With mission, vision, and values in place, the board can next move on to providing more specific organizational direction. Again in conjunction with the staff, stakeholders, and community, the board asks:

- What outcomes will move us toward our vision?

- Who are the beneficiaries of our work?

- What resources do we need to realize our desired outcomes?

These questions keep the board focused on outcomes rather than the means for producing those outcomes. The staff ultimately defines the means, but those means must fit within the defined organizational values and be legal, ethical, and prudent.

As the organization moves forward in the direction set by the board, the board must assess the impact of various initiatives using mission, vision, and values as the framework for evaluation. Questions to ask to assess impact are:

- Are we achieving the desired outcomes? If not, why not? What are the barriers?

- Does our work fit within the defined mission?

- Are we working according to our organizational values?

- What are we hearing from the staff, stakeholders, and community?

- Do we need to adjust our goals and/or our thinking?

- Are there external factors that might require us to change what we do? What do we see on the horizon?

CYCLE OF GOVERNANCE

During the process of assessing impact, the board needs to be flexible and nimble in its thinking. It must also be willing to adjust its strategy or change course if current reality indicates such a need.

Finally, in order to complete the cycle, the board needs to reflect on its own work. One way is to conduct a self assessment. There are many ready-to-use instruments available, and most of them are well designed. This part of the cycle, however, is more than just a once-a-year assessment. It refers to ongoing reflection and learning that informs the governing process and that is built into how the board works as a team.

Together these tasks create a virtuous cycle of impact through which the board continually learns and builds capacity. Although represented here as discrete steps, they are far from separate. In fact, all of them can happen in concert, creating a web of interrelated activities.

Systems Thinking Framework

Developing prowess as a board is a never-ending process of both personal mastery and team learning that is particularly challenging, considering the players change on an annual basis. Applying systems thinking to board governance can create a common framework within which board members can practice their craft. It’s the common thread or foundation for developing the team, governing effectively, and ultimately building capacity.

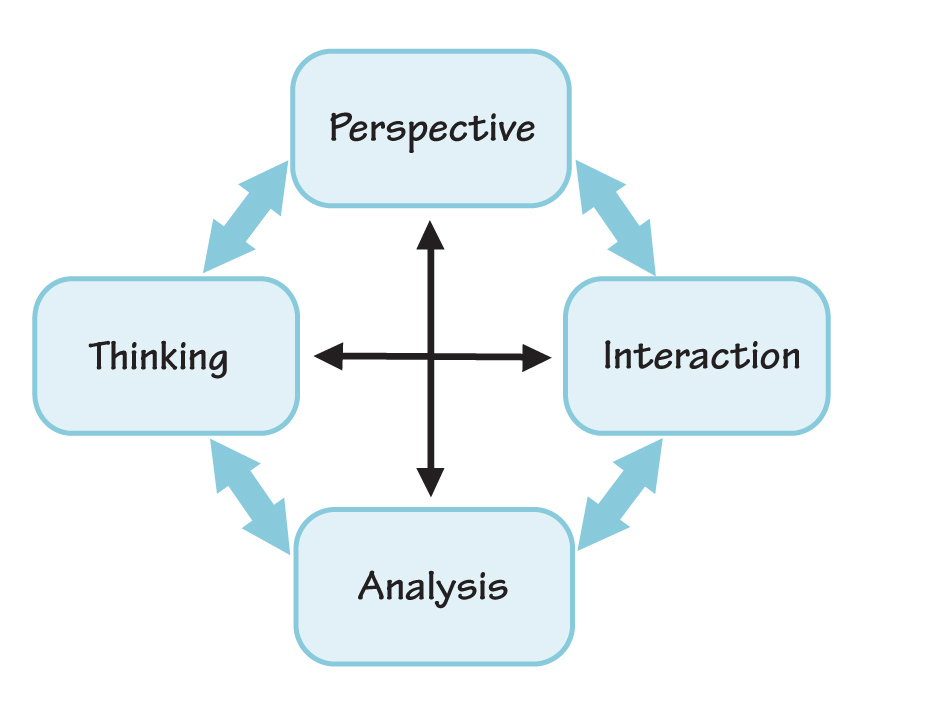

Because systems thinking is a fairly complex discipline, breaking it down into smaller components will help board members understand how powerful it can be in the practice of governance. These components are woven throughout the governing process and are represented by the following four functions: perspective, interaction, analysis, and thinking (see “Systems Thinking for Board Governance”).

Perspective. The starting point for any board is to be clear about its perspective. Boards must engage in big-picture thinking, looking at the organization’s whole system, both internally and externally. Two aspects are critical for determining perspective. The first is ensuring that the whole system is “in the room.” Boards can’t govern in a vacuum – they must engage their staff, stakeholders, and community in conversations that inform the governing process.

The other aspect of perspective for boards to consider is the extent to which board members focus on detail complexity versus dynamic complexity. The field of governance training often characterizes this distinction as staff versus board roles, but as with any organizational function, it really isn’t that simple. The board needs to determine what operational variables are important to follow so it can track long-term trends.

Interaction. Another key area where boards can usefully apply systems thinking involves how they interact with their constituents. Engaging in dialogue, creating a shared vision, and encouraging inquiry are all critical means for eliciting feedback from the system. Moreover, the interaction must happen at the appropriate level of perspective for the board, that is, members must engage with constituents from a big-picture perspective. They must be skillful at asking questions that help bring their constituents up to that higher level of thinking. Otherwise, they will find themselves mired in detail complexity.

SYSTEMS THINKING FOR BOARD GOVERNANCE

Analysis. Boards can also improve the quality of their governance by using systems thinking to improve analysis. As a board develops a vision, it must also assess current reality as accurately as possible. In doing so, the board will need to hold the creative tension between the current reality and vision as the organization moves forward. This path, however, is typically not smooth, and unintended consequences will occur. At this point, the board must be able to step back and determine root causes for those unintended consequences, knowing that the quick fix is often short-lived. Asking why, avoiding blame, focusing on outcomes, and looking for patterns over time will all help the board identify root causes and design sustainable solutions.

Thinking. A board’s thinking is the final component in this puzzle. When a board faces what seem like intractable problems, it must identify and challenge long-held assumptions that may be barriers to achieving the vision. It must continually reflect on performance, both its own and that of the organization, and learn from that reflection.

Ultimately, the four components discussed above comprise a systems thinking framework that boards can apply to their practice of governance.

An Application: Identifying Leverage Points

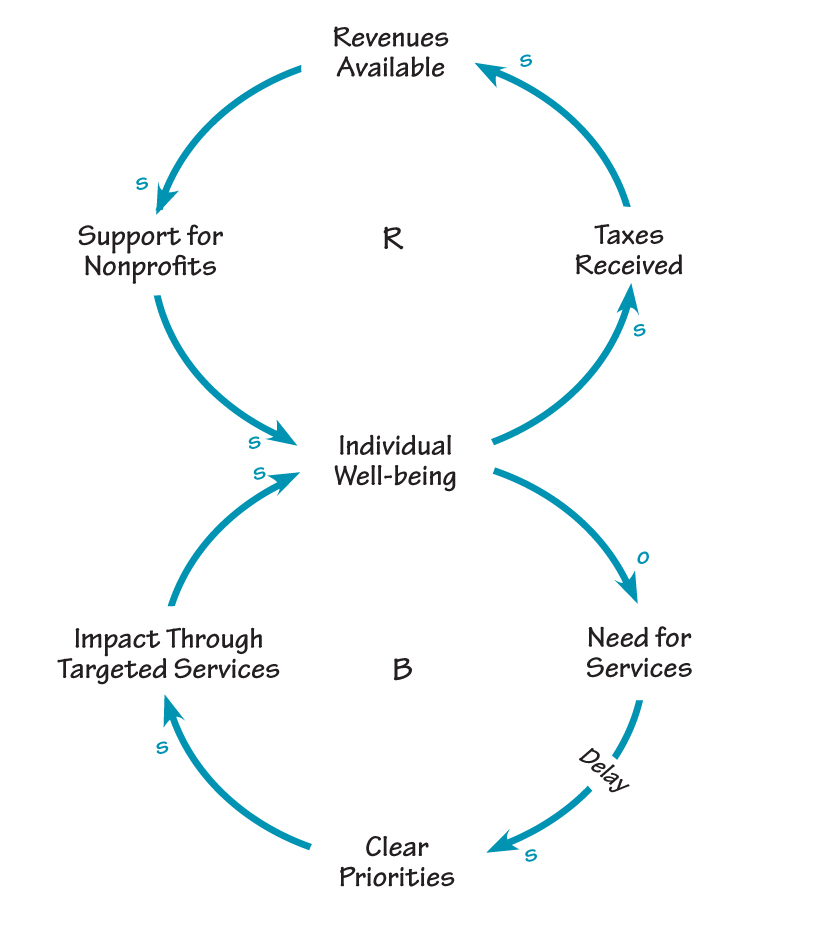

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, many nonprofits and their boards have faced difficult decisions as the economic crisis has unfolded. In particular, many municipalities with lower-than-expected tax revenues made the difficult decision to cut or eliminate funding for local nonprofits that they had long supported. Subsequently, those nonprofits scrambled to fill the financial gap, or ultimately cut programs and services. What resulted was a vicious cycle of hardship for everyone.

A NONPROFIT FUNDING CRISIS

Let’s look at how systems thinking can help identify leverage points for effective action in this structure. The causal loop diagram “A Nonprofit Funding Crisis” has two loops: a reinforcing loop at the top and a balancing loop at the bottom. The presenting symptom that is the focal point of this problem is the fact that individual well-being is declining because of the recession. In the reinforcing loop, many municipalities have experienced declining tax receipts. In response, they lower or eliminate support for local nonprofits. This action eventually has a negative impact on individual well-being, because those local nonprofits are likely to reduce or eliminate the programs and services they offer, causing well-being to decline further. Thus we have a seemingly endless downward spiral.

However, we find leverage in the balancing loop. As individual well-being decreases, the need for services increases. Even with level funding, a sharp increase in demand requires clear priorities about when, where, and how resources will be used. Evaluating priorities takes time, and thus there is a delay in the system at this point. With clear priorities, nonprofits can target resources for where they will have the greatest impact; in doing so, they ultimately improve the well-being of individuals.

The highest leverage in this system is how the priorities are set. Nonprofits and municipalities must come together with community members to discuss priorities (whole system in the room), determine potential consequences and impact, and finally develop a plan for alleviating the symptoms while addressing the root causes. The fundamental solution for improving well-being is likely to be complex, involving several different approaches and many organizations over time.

Time to Practice

The challenge for any board faced with a difficult decision that requires immediate attention is taking the time to step back and engage in systems thinking. The quick fix pulls at our desire for an immediate solution, and the multiple demands on our time push us in that same direction. The key to applying systems thinking as a board is to begin to practice it when the organization is not in crisis. There is no better time to begin changing how a board thinks and operates than when it has the time to practice. It is that practice that will enable the board to create virtuous cycles of impact over the long run.

© Marty Jacobs 2010

Marty Jacobs, president of Systems In Sync, has been teaching and consulting for 20 years, applying a systems thinking approach to organizations. Her practice focuses on strategic planning, board development, community engagement, organization development, and team facilitation. Additionally, Marty has served on a variety of nonprofit, professional, and school boards over the past 20 years. A graduate of Dartmouth College, Marty received her M. S. in Organization and Management from Antioch University New England in Keene, NH.