One of many recent articles on the current financial crisis noted that it could only have occurred because so many people were willing to sacrifice long-term interests for short-term gain. It appears that the accrual of future costs at the expense of instant rewards blindsided most lenders, borrowers, and regulators. Unless we fully understand and address the dynamics that led to the crisis, even further economic disruption is likely.

We can learn how to recognize and work more effectively with these dynamics by applying systems thinking to:

- Illuminate the often non-obvious interdependencies among multiple elements that create such problems,

- Increase awareness of how people unwittingly undermine their own efforts to achieve their stated aims, and

- Point to high-leverage solutions that benefit the system as a whole.

This article briefly introduces several principles for analyzing the root causes of complex problems; applies them to gain a deeper understanding of the current financial crisis; and recommends high-leverage actions that political and business leaders can take to improve economic performance in sustainable ways.

TEAM TIP

Since unexpected outcomes are so common, build processes for learning and correction into all decisions.

The Instability of Reinforcing Feedback

The performance of a complex system is largely determined by interdependencies among its elements, many of which are indirect, circular, and non-obvious. Perhaps the most salient of these relationships is reinforcing feedback, which explains the dynamics of both exponential growth and spiraling decline. Such phenomena as compound interest that dramatically increases savings over time and engines of business success that fuel expansion are familiar illustrations of positive exponential processes. On the other hand, vicious cycles such as epidemics and economic collapse are indicative of negative reinforcing feedback.

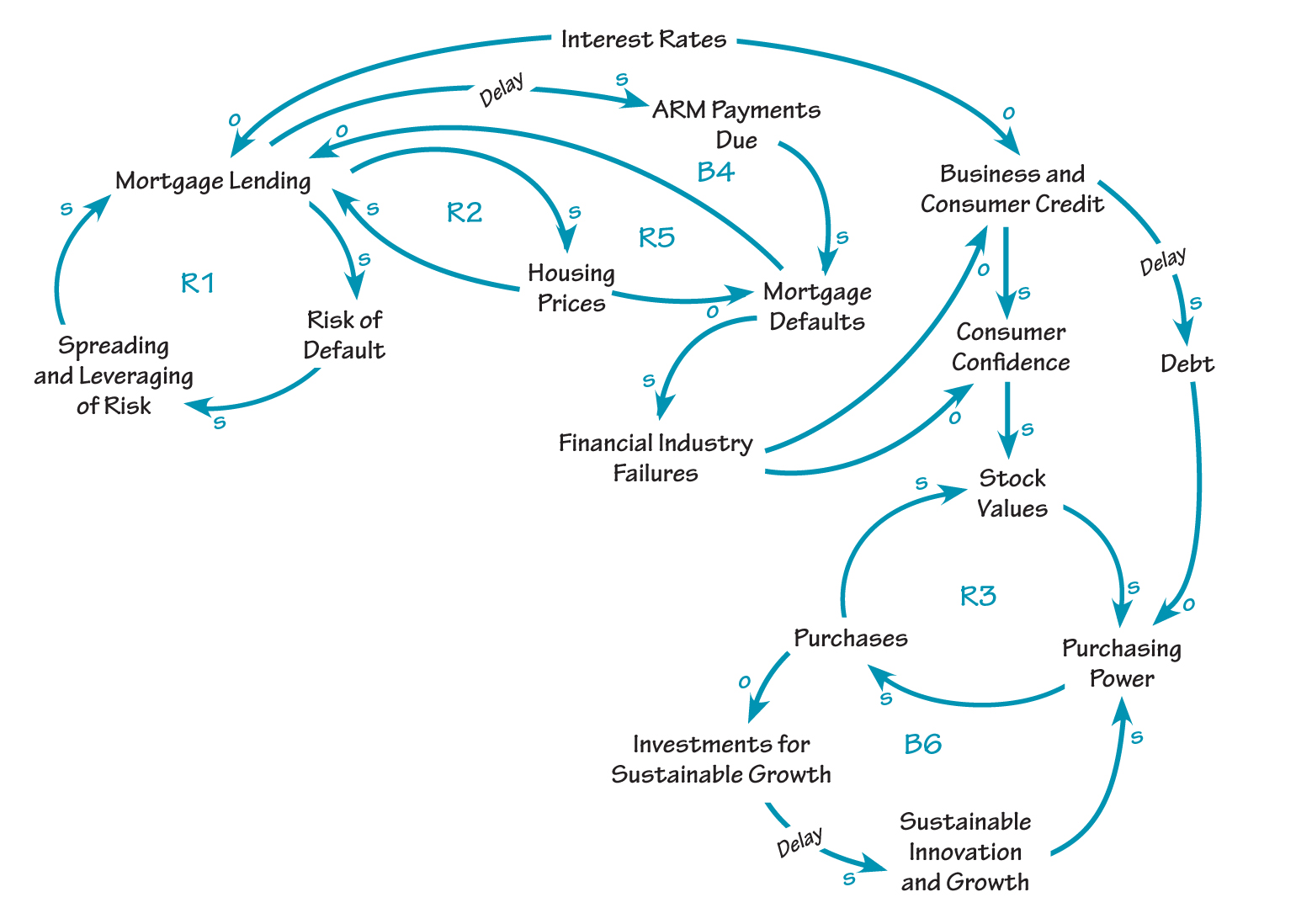

In order to understand the current financial crisis, we first need to recognize that the same engines that stimulate exponential growth can also lead to sudden collapse. Economic bubbles tend to burst, and bull markets can suddenly turn into bear markets. In the case of the recent housing bubble, low interest rates generated easy credit, which was amplified by new financial instruments such as credit default swaps that spread and leveraged investor risk. Easy access to mortgage money increased housing prices — until higher adjustable mortgage rates kicked in and led to mortgage defaults and foreclosures, steep declines in housing prices, the collapse of key financial companies, and the tightening of credit.

In the case of the stock market, rising credit led to increased consumer confidence and increasing stock values, which in turn created greater purchasing power and fueled more purchases and higher market values. However, the sudden loss of confidence spurred by the financial crisis and declining stock prices has now led to reduced purchasing power, belt tightening, and a widespread recession. The bear market is intensified by (1) the long-term accumulation of debt resulting from credit-driven growth, and (2) the dependence of the previous bull market on purchases of largely non-renewable consumer and military products that have undermined investments in more sustainable innovations and growth. The dynamics of reinforcing growth and collapse are summarized in “The Instability of Reinforcing Feedback.”

Two high-leverage strategies for avoiding the dependence on reinforcing feedback as an unending source of growth are:

- Anticipate and prepare to address natural limits to any growth process. This means remembering that there are no free lunches and that promises of infinite growth inevitably prove false.

- Evaluate and manage growth in relation to independently meaningful goals rather than as an end in itself. We need to understand that money can enhance the quality of our lives by making it easier to realize our aspirations and express our values, but that the single-minded pursuit of money is ultimately deadening.

Managing Unintended Consequences

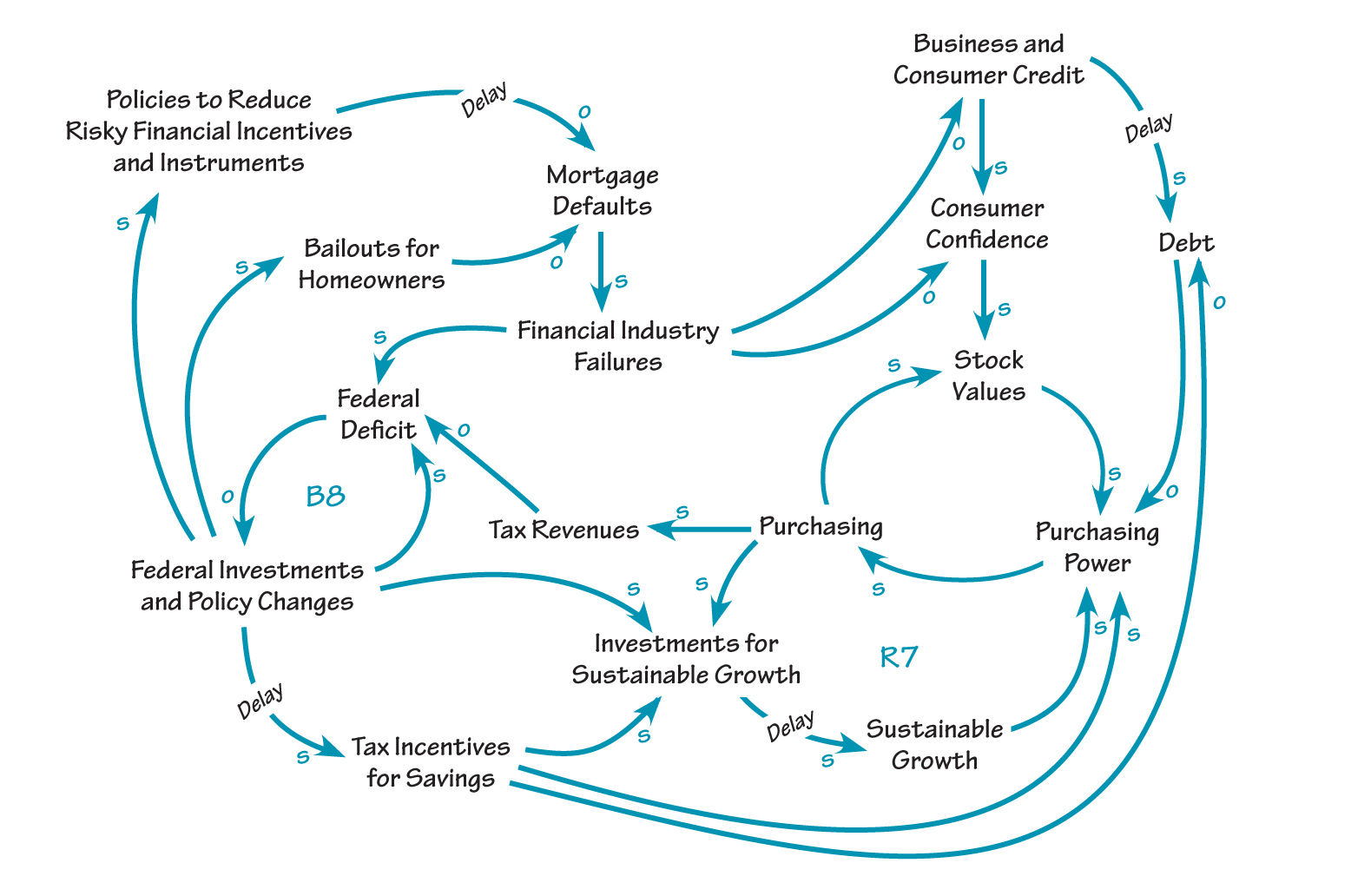

Another systems principle is that most quick fixes have unintended and delayed consequences that usually neutralize or reverse immediate gains over time. In the case of the current financial crisis, the bailout not only risks significant complications in years to come, but has also led to negative unintended consequences in the short term. First, the bailout has not achieved its immediate aims of opening credit markets or increasing consumer confidence, because banks have largely held onto the money to ensure their own solvency. Second, the resulting increase in the federal deficit, which will be compounded down the line by looming increases in Social Security and Medicare payments, will likely create significant tax increases that reduce purchasing power even further. A higher federal deficit will also generate inflation that reduces purchasing power and increases interest rates, thereby further limiting people’s ability to borrow as a way to stimulate growth.

THE INSTABILITY OF REINFORCING FEEDBACK

One higher-leverage way to shift these dynamics is to address the root causes of the financial industry collapse instead of just its symptoms, i.e., prevent foreclosures by restructuring the mortgages of people at risk, and change the financial rules of the game (including incentives and instruments) that led to the collapse in the first place.

The performance of human systems is significantly affected by people’s deeply held beliefs and intentions. With regard to our economic system, many political and business leaders believe that growth measured primarily in financial terms is inherently good and that the ultimate goal of the system is to increase it. This belief results in high pressure for growth, which our country has tended to achieve by stimulating borrowing instead of savings (at the individual, corporate, and national levels) as the basis for investment, and encouraging spending, especially on consumer products and a strong military. For example, consumer spending has been spurred by low interest rates, and military spending has been increased to combat terrorism. The consequences of these strategies include increased deficits (again at all levels) and relatively low investment in renewable resources such as education, research and development, preventive healthcare, and alternative energy.

In order to reduce the high costs of an economic paradigm based primarily on financial growth, we need to shift to a new paradigm designed to achieve sustainable development. This entails:

- Reallocating federal spending and redesigning tax incentives to develop renewable resources such as people and alternative energy.

- Stimulating consumer and business spending based more on interest earned from savings than on interest paid for loans. One way to encourage savings is to gradually shift the tax structure toward reducing income taxes — because earned income tends to generate economic value — while increasing sales taxes (with credits for low-income families) — because consumption often destroys value.

This kind of economic stimulus package can reduce the federal deficit in the short term by decreasing mortgage defaults and thereby strengthening the financial industry. The deficit would decline in the long term due to changing policies that reduce lending risk and increase savings, and by the higher tax revenues generated from a more sustainable economy. These strategies for meeting the financial crisis and redesigning how we approach our economy are shown in “Framework for a New Economy.”

Facilitating Continuous Learning

s In addition, there are several other applications of systems principles that can help political and business leaders make wiser decisions about how to respond to the current economic crisis:

- Because most actions have both unintended and intended consequences, decision makers should always ask themselves what might be the accidental impacts of the solutions they propose before acting. Congress attempted to do so in challenging the bailout, but the fear of further immediate financial collapse resulted in Congressional approval without adequate oversight of how the money would actually be spent.

- Since unexpected outcomes are so common, processes for learning and correction should be built into all decisions. For example, since the bailout has done little to restore the economy so far and many people question its underlying rationale, policy makers and analysts should deeply question the reasons for the shortcomings and make adjustments as needed.

- Most actors in a human system unwittingly create or contribute to the very problems they are trying to solve. This means that as part of the learning about the bailout, decision makers must question their own responsibility for the problem rather than blame other stakeholders for what happened.

- Changes in complex systems often require significant time and patience to take hold. Therefore, any short-term learning and correction needs to be carefully judged against a theory of change that explicitly takes time delays into account.

FRAMEWORK FOR A NEW ECONOMY

In summary, systems thinking can support decision makers to increase both the short- and long-term effectiveness of their decisions. The current financial crisis offers an opportunity to alter previous policies and transform the way we develop our economy.

David Peter Stroh is a principal with Bridgeway Partners (www.bridgewaypartners.com) and a founding director of Applied Systems Thinking (www.appliedsystemsthinking.com). His areas of expertise—developed over a 30-year career consulting with private, public, and non-profit organizations around the world—include applying systems thinking to facilitate organizational and societal change, visionary planning, and leadership development.