It’s no surprise to most executives that we are in the early days of a major technological revolution that has had — or will have — an impact on almost every aspect of the way we do business. The unprecedented rate of change that has accompanied this upheaval is outpacing our ability to create newly adaptive product strategies and organizational structures. In the past, businesses have taken 10 to 20 years to adopt new management theories that fit the demands of a changing environment. For instance, although Deming and Juran articulated their breakthrough ideas about quality in the 1950s and 1960s, U. S. companies didn’t implement those concepts until the 1980s, and then only under the crisis of foreign competition. But we no longer have the luxury of decades to close the gap between our current capabilities and the demands of technological change.

In this new context, managers must develop a different mindset. They need to deal with a high level of unpredictability and accept the incompleteness of our knowledge base. Moreover, they need to act on the fact that the key differentiating factor between success and failure will be the ability to learn collaboratively with others — both within and outside of their organizations.

THE LEARNING NETWORK

Why collaborative learning? In the current business climate, no one person or organization can bridge the chasm between present levels of skills and knowledge and the level of understanding necessary to take advantage of breaking technologies. The challenges of the global economy require that we join with customers, vendors, competitors, and partners from other industries to share insights. Organizational survival into the next century may well depend on our ability to configure collaborative arrangements within and across organizations — quickly, flexibly, and with a clear learning strategy. Companies that cannot network with others to share key knowledge — using the latest technology — will fall hopelessly behind their rivals.

The Practice of Collaborative Learning

What is collaborative learning, and what does it entail in practice? Collaborative learning is the process of generating new knowledge and capability that occurs when two or more people explore key business issues together, with the goal of fulfilling organizational needs and continually building their ability to work and learn in tandem. The practice of collaborative learning moves relationships beyond the mere exchange of information that characterizes most project teams or corporate partnerships. Collaborative learning begins at the individual level. For it to take root in an organization, employees must first develop a collaborative mindset and a collaborative skillset.

A Collaborative Mindset: Seeing New Opportunities

Individuals who adopt a collaborative mindset maintain an active awareness of the collaborative learning potential in every business transaction. They possess an openness and keen interest in others’ perspectives, and develop the ability to gather resources to experiment with and implement new ideas. These employees realize that their own tacit knowledge — when combined with a colleague’s tacit knowledge — may hold the key to a new innovation. Therefore, individuals working from this orientation constantly seek opportunities to explore collaborative potential with partners, coworkers, and even those who seemingly have no direct connection to the business. They leave themselves open to serendipitous opportunities for new partnering that may arise on airplanes, in shopping malls, or in other environments that we typically do not think of as supporting learning.

But a collaborative mindset at the individual level is not enough. To foster this same mindset on an organizational level requires that a firm understand the learning and data acquisition styles of partner organizations. Then the firm must deliver information and knowledge in forms that partners can use. This activity can be as simple as providing a list of the organization’s commonly used acronyms, or as complex as opening the company’s intranet to partners so that they may understand the firm’s inner workings.

When companies become aware of the potential in collaboration, knowledge-generating opportunities arise both by conscious design and by chance. For example, a manager at one firm gave a presentation to a partner company, knowing that a dissatisfied customer sat in the audience. By working from a collaborative mindset, this manager openly engaged the customer in recounting the problems he had experienced with the product and made a commitment to remedy the situation in front of the audience. Over time, this collaborative stance led to a new partnership with the now satisfied customer and resulted in several joint projects, including one at a major airport. Working from a collaborative mindset means continually seeking opportunities to build on existing relationships, and turning neutral or negative circumstances into advantageous ones.

A Collaborative Skillset: Spanning Boundaries

In addition to developing a collaborative mindset, individuals need to build a set of competencies that let them cross boundaries between groups and companies, learn from others, and disseminate that learning throughout their organizations. The six “boundary-spanning skills” described below provide managers with the tools they need to work more productively with others — within and outside of the organization — and to create and manage the knowledge gained through those interactions (for a boundary spanning competency model, go to www.pegasuscom.com/model.html).

Double-Loop Learning. The usual approach to a new experience or piece of data is termed single-loop, or adaptive, learning. (These concepts derive from the work of Chris Argyris.) Single-loop learning occurs when we alter our actions based on new information but we do not question the assumptions and beliefs concerning that data. We see an example of this in how organizations typically handle failure. Analyzing the “lessons learned” from a particular problem may be valuable, but it often results in a list of do’s and don’t’s — single-loop learning. This technique doesn’t delve into the assumptions that brought about the shortfall, nor does it seek to change the system created by those assumptions. In double-loop, or generative, learning, when we encounter failure, we explore our assumptions and commit to behaving differently in the future. Developing skill in double-loop learning involves increasing our awareness of the filters and suppositions that we use to interpret reality, and acting on this insight.

Communication (Dialogue, Feedback, Listening). Effective boundary-spanning relies on hearing, understanding, and empathizing with others. This ability involves listening not only to others but also to ourselves to uncover hidden biases. The practice of dialogue, as first defined by physicist David Bohm, can help. Dialogue supports divergent communication, in which a group allows a stream of viewpoints to flow through the conversation without feeling a need to reach a set conclusion. It also teaches us how to listen to others without judging them. Another component of boundary spanning communication is the capacity to give and receive feedback. This challenging skill helps us to see beyond our own view of reality and improves our ability to communicate with others. Tactfully done, feedback conveys potentially ego-damaging information in a neutral and helpful way. Mediation. As organizations continue to move toward flattened hierarchies, they have less need for traditional management techniques. Instead, they must help their workers learn to influence their peers in productive ways. In particular, mediation capabilities let parties go beyond political maneuvering and a winner-take-all attitude to achieve alignment through a focus on shared interests.

Systems Thinking. Systems thinking provides the essential backdrop for understanding the cause-and-effect relationships between organizations and their larger environments. This perspective highlights the functioning of the system as a whole, rather than the discrete parts that make up that system. The systems thinking toolbox — which includes causal loop diagramming, systems archetypes, stock and flow diagrams, and other tools — provides a powerful methodology for surfacing barriers to change, identifying leverage points for effective action, and building new connections.

Peer Learning. Peer learning is a vital and, in many cases, the most effective form of learning. Traditional corporate learning models involve either in-house classroom training or university courses. These methods emphasize the transfer of theory and case studies from the expert to the student. In current business practice, however, learning must take place “just-in-time,” with theory and practice developed in parallel and all players taking part in problem-solving activities. The concepts of self-directed work teams, 360-degree feedback, and communities of practice all support the increasing relevance of peer learning.

Cultural Literacy. Research shows that success in managing relationships with individuals from other cultures hinges on flexibility, openness, sensitivity, tolerance, curiosity, the ability to handle stress, and a sense of humor. Even armed with these skills, people can still fall victim to their own cultural values and assume that their perspective is the right one. This attitude can spawn unexpected conflict. To work successfully on a global level, organizations must continuously build awareness of cultural differences among employees and help them develop a level of comfort working across cultural boundaries. Such awareness emerges primarily from actual interactions with members of other cultures; it cannot be acquired from books and lectures, no matter how engaging or insightful.

A Collaborative Environment

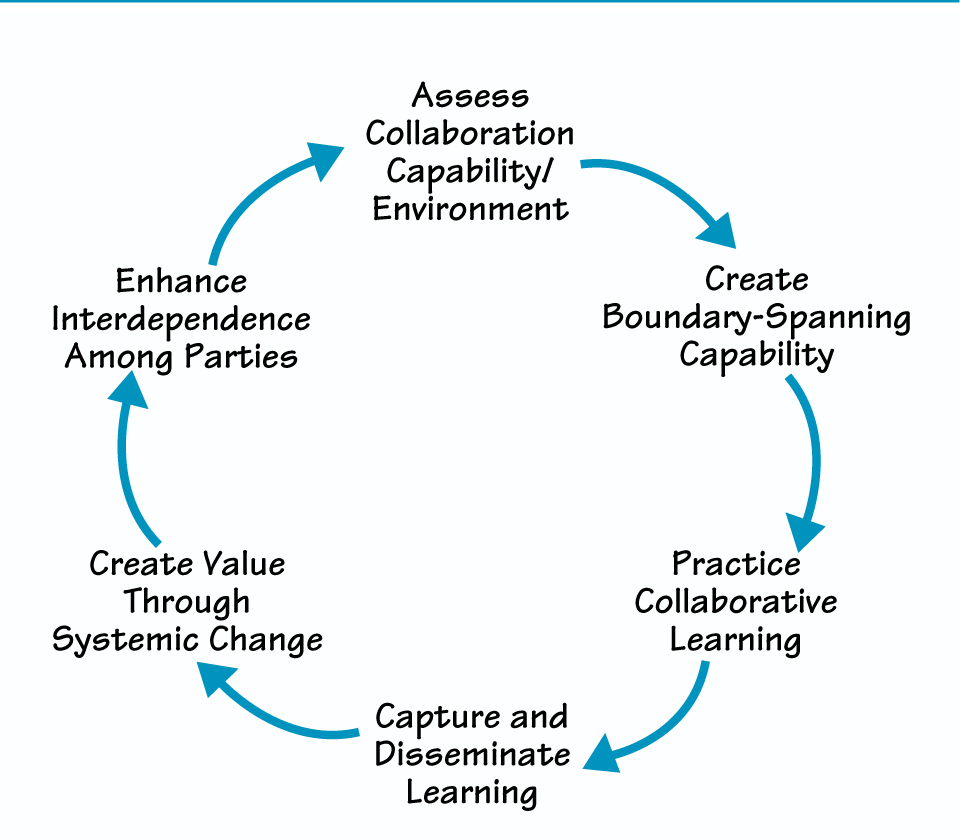

By combining a collaborative mindset and skill set, managers acquire the skills and flexibility they need to move their organizations forward. As a result, they can inspire individuals to cross boundaries, learn from others, and disseminate that learning through-out the organization (see “The Collaborative Learning Cycle”). Such boundary spanning activities give workers access to business expertise in the moment — and can lead to rich, new insights.

However, there is another prime ingredient necessary for collaborative learning: the organization must support and sustain a collaborative environment. Organizational consultant Edward Marshall defines a collaborative environment as consisting of:

- A Collaborative Culture: a set of core values that shape a business’s behavior, including respect for people, honor and integrity, ownership and alignment, consensus, trust-based relationships, full responsibility and accountability, and recognition and growth

- Collaborative Team Processes: including team formation, management, self-sufficiency and renewal, and closing processes

- A Collaborative Structure: support for collaboration from human resources and information systems

- Collaborative Leadership: the ability to recognize many leaders, not just one; these leaders fulfill a number of functions, such as facilitator, coach, healer, member, manager, change agent

THE COLLABORATIVE LEARNING CYCLE

How can an organization bridge the gap between individuals’ development of a collaborative mindset and skillset and the company’s development of a collaborative environment? One way is to form an internal learning group. Drawn from various divisions and levels within the company, such a group focuses on building collaborative capability — and deriving business results from that enhanced capability — within the organization.

These groups begin by assessing the organization’s level of support for collaborative efforts. For example, one company found that workers failed to share technical information across departments because they didn’t understand the firm’s policies regarding intellectual property. In this case, the organization provided additional training to help employees work through these concerns.

Internal learning groups cultivate boundary-spanning skills and practice collaborative learning themselves in addressing the company’s business challenges. For example, a small West-Coast chemical company experienced communication barriers after merging with a lab on the East Coast. Management assembled a group consisting of members from each of the merged entities to address issues of collaboration. This team put together a personnel directory and a compendium of technical success stories from both firms. In addition, it designed a plan for an organization-wide session to inform employees about the merged organization’s new accounting processes, lab procedures, technical competencies, and customer care approaches. In the process, the group discovered pockets of people who were interested in exploring collaboration. Encouraged by this finding, it began to support ongoing experiments in collaborative learning, such as periodic meetings of project managers to exchange knowledge and practices.

These internal learning groups also play a central role in disseminating new knowledge throughout the organization, using tools such as after-action reviews, internal publications, and intranets. The sharing of cutting-edge tools and ideas with other teams creates value because it improves processes and hones collaborative skills. For example, the learning group of a Fortune 500 company experimented with the use of e-meeting software and disseminated that knowledge throughout the company through the technical staff. Finally, the learning group members experience an enhanced degree of interdependence, which steps up collaboration — and performance — even further. The group’s process both begins and ends with a reassessment of the organization’s collaborative learning capability, at an increasingly fine-grained level of inquiry.

Forming a Learning Network

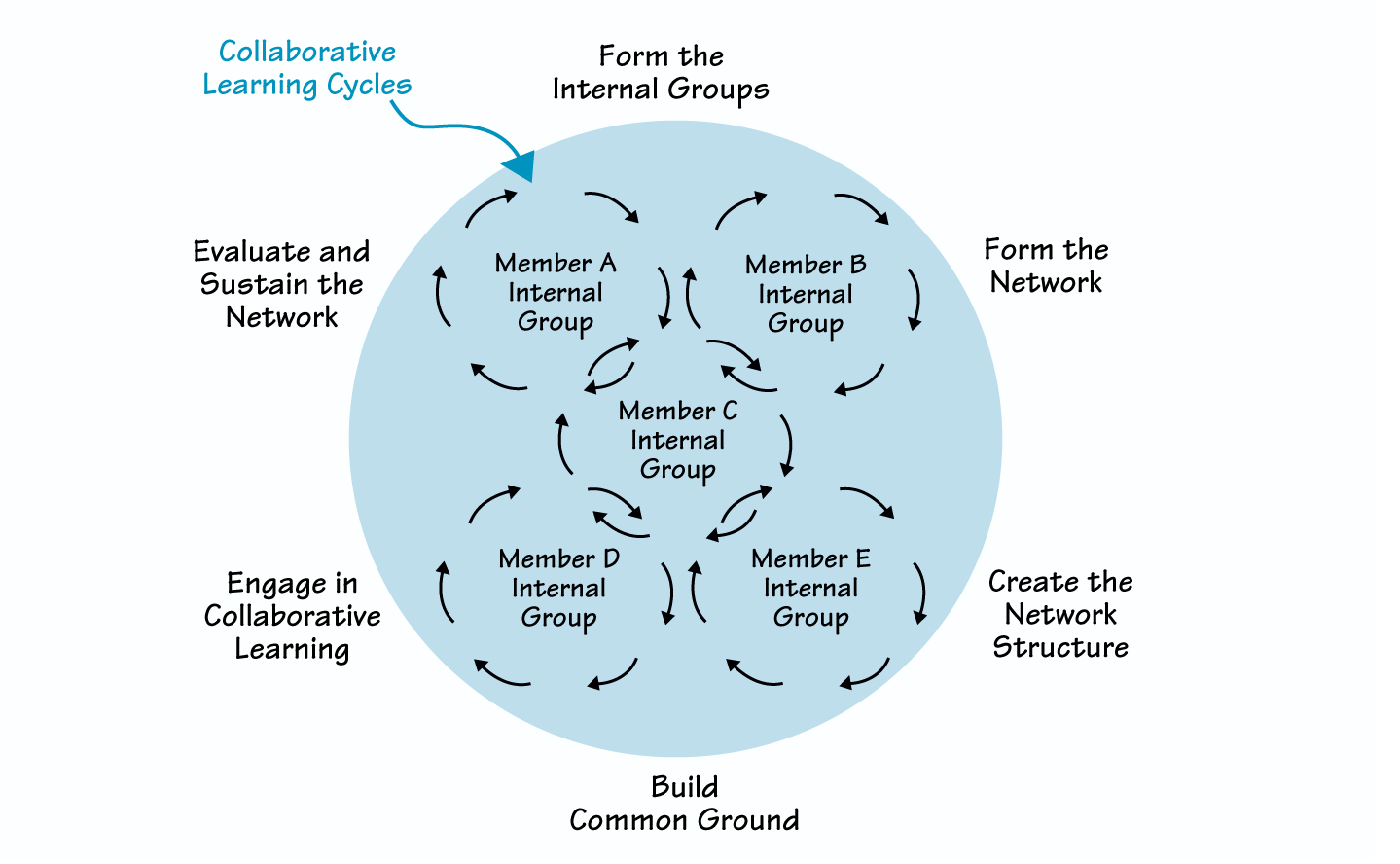

Once the internal learning group has completed some successful projects, it will likely encounter barriers to moving the organization to a fully collaborative environment. These barriers often take the form of inherent conflicts between espoused beliefs, such as “We are a collaborative company,” and core values, such as “The individual is who counts here; watch out for number one.” One way to surmount these barriers is for the group to participate in a learning network (see “The Learning Network” on p. 1), drawn from the work of Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Edgar Schein on the learning consortium.

A learning network is a cross-organizational forum in which internal learning groups from diverse organizations can explore challenges together. Group members come together on a regular basis to give and get feedback and create new knowledge. The interaction among the parties sparks behavioral changes that create value for each organization. This is because outsiders may have a more objective view of an organization’s operations and strategies than do those who are involved in the firm’s day-to-day operations. For example, when an information technology company’s learning group presented a new project for a Web-based internal instructional system to the other members of its learning network, someone from another company asked how it would implement the program in countries where Internet access is limited. This query served as powerful feedback for the presenting group.

For a learning network to succeed, the organizations involved must decide how to deal with differential power among the stakeholders; define the network’s mission, goals, and norms; involve dedicated and trained participants; develop a level of trust among individuals and organizations; and assume a win-win orientation. Each member group engages in a process of experimentation, application, and dissemination of knowledge within its own organization. The network member groups then meet regularly to share knowledge and to engage in collaborative projects across organizations. These projects can take the form of joint research, standards setting activities, experimentation, problem-solving, or peer-teaching seminars. Interdependence and trust strengthen when network members follow through on commitments, provide feedback, and come to new insights together.

FORMING A LEARNING NETWORK

Form the Internal Groups

- Assess the organizational culture and collaboration capabilities.

- Build boundary-spanning competencies.

- Create internal mission and goals.

Form the Network

- Determine a purpose.

- Define the membership.

- Make contact.

- Exchange information.

Create the Network Structure

- Meet to establish common ground.

- Define network mission/goals.

- Decide structure and duration.

Build Common Ground

- Agree on means of communication.

- Further develop boundary-spanning practices.

- Identify and build on organizational interdependencies.

Engage in Collaborative Learning

- Create and execute programs.

- Share resources.

- Capture and transfer learnings.

Evaluate and Sustain the Network

- Review business measures.

- Evaluate the process and make adjustments.

- Reinforce rewards and incentives.

Renew or Close the Network

- Revisit mission and create new goals.

- Design closing meeting.

- Assemble learning history.

- Establish mentors.

The ongoing support and vitality of internal learning groups is central at this stage. To create value within their home organizations, member groups in the learning network must capture and transfer learnings from the network’s cross-organizational programs. They can do so through ongoing activities that link internal groups’ projects to the network. This might include visits between companies, the design of collaborative spaces — both physical and Web-based — for network activities that are broadly accessible to members, and frequent face-to-face and virtual meetings, both internal and cross-organizational.

For instance, the Collaborative Learning Network is a consortium of seven companies from a variety of industries dedicated to understanding how collaborative learning can enhance organizational performance. Its members have engaged in a series of monthly virtual seminars over the past year that link semi-annual face-to-face meetings. Network members have found that experimenting with virtual processes for cross-firm communication has directly helped their business units build expertise in collaborative tools. Below are some findings from these joint experiments:

- For virtual meetings, simple tools like phone conferencing, e-mail, and Powerpoint presentations shared on the Web work best. These tools are standardized across organizations and platforms.

- Synchronous meetings, whether face to face or virtual, garner more consistent participation than more open-ended, asynchronous methods, such as Web-based discussion boards.

- Information overload is at best irritating and at worst debilitating. Networks must find a balance between “push” (e-mail, phone, print) and “pull” (Web sites, scheduled events, conferencing) methods of information exchange.

Of course, companies must receive a return on their investment in collaborative processes. Questions to pose in assessing learning network results include: What has been the bottom-line impact of new sources of learning? Have new applications of technology emerged from the network activities? If so, are they now producing profit or cutting costs? Has senior management acted on any feedback received through the learning network’s activities? If so, what has been the outcome?

Each learning network will have a natural life cycle. Once the initial period of activity has concluded — as agreed at the outset — the network members need to enter a closing or renewal phase. If the network chooses to disband, then the participants should schedule a formal closing meeting to celebrate the network’s achievements. Members might also document the network’s experiences in some final form, such as a learning history. As a final outcome, members could assemble a core group of mentors willing to guide other individuals in each organization who may wish to initiate their own learning network (see “Forming a Learning Network”).

Bringing It All Together

If used skillfully, collaborative learning can improve work performance; heighten strategic awareness; enhance responsiveness to changes in the marketplace; and foster more productive relationships with customers, vendors, and other stakeholders. It can also encourage teams to experiment with fresh approaches for addressing problems and for working and thinking together. By combining collaborative awareness and skills at the individual, group, firm, and inter-firm levels, organizations can effect significant and lasting change. In this challenging climate, we all need to develop powerful new models of partnership and learning. Collaborative learning offers a structured way for organizations to quickly adapt to the needs of a changing business environment — to the benefit of individual employees and the organization as a whole.

Dori Digenti is president and founder of Learning Mastery, an education and consulting firm focusing on collaboration and learning. Over the past 20 years, Dori has worked with business, academia, and government to develop cultural literacy, learning capacity, and collaborative competence. She has written the Collaborative Learning Guidebook (1999), as well as articles for Reflections: The SoL Journal, the Organization Development Journal, and other publications. Dori is webmaster for www.learnmaster.com, www.collaborative-learning.org, and a forthcoming Web site on the work of Edgar Schein.

NEXT STEPS

- Begin to look at the collaborative environment in your firm. Does what management say about collaboration and teamwork match the reward system, company lore, and your colleagues’ actions? Find out where the gaps exist between policy and action.

- Build the case for developing the collaborative skillset. In some companies, this activity will fall under the aegis of leadership development. In others, it will be part of the push for effective teamwork. Find the trainers and leaders of these efforts and get their feedback about how to build boundary-spanning skills.

- Seek outside input. This is the best way to avoid reinventing the wheel. Advice from peer organizations struggling with similar business issues can help to overcome “not-invented-here” attitudes in the organization.

- Become familiar with the new virtual tools supporting collaborative work. Insist that your company invest in building the skills to use these tools, such as e-meeting software. In a few short months, these tools will be considered must-haves for successful partnering initiatives.