As a writer, on a handful of occasions, I’ve produced work that stands far above everything else I’ve written. This work has a special quality to it that can, in part, be explained by how it was written. In almost all instances, I was doing something different from sitting in front of an empty page, trying to write.

The clearest and most powerful instance occurred one winter evening while I was sitting on a bus, looking out at passing traffic. In a moment, an entire story came to me. I immediately got off the bus, found a bench, pulled out a notebook, and wrote. Words and sentences came to me almost fully formed. Afterward, when I looked at the story, it glowed. While it was “mine,” in many ways, I didn’t write it; it simply came to me, whole and complete. I was the vehicle for it to emerge.

TEAM TIP

Such experiences are, of course, universal. When asked how he came up with the theory of relativity, Einstein explained that an image of riding on a lightning bolt came to him one day. In thinking about what things would look like from the perspective of the lightning bolt, he started down the path that led him to articulate the theory of relativity.

The same phenomenon can be seen in art, science, and wherever else innovation occurs. We commonly think of this process as insight. There are modest insights and great insights. There are insights that we forget in a few minutes and those that change the trajectory of our lives and sometimes of all humankind.

If we examine the history of many legendary innovators, scientists, artists, writers, and entrepreneurs, we see a common pattern. Each spends many years simply trying to understand their subject through research, fieldwork, or experimentation. This exploration is followed by an “aha” moment. At this point, the innovator’s work takes on a different quality, characterized by startling clarity as to what to do next. This insight is like a seed; the individual’s life work then becomes the task of growing this seed to its full potential. While the earlier phase was about traveling many paths, after the insight, the innovator’s purpose is to travel down this one shining trail.

In his youth, the legendary Lakota healer and warrior Black Elk had a number of frightening, epic visions. In one, which he called the “Dog Vision,” it became clear to him that he must fight against the “Wasichus” (a term that refers to European invaders). He recalled sharing the vision with his tribe: “I told it all to them and they said I must perform the dog vision on earth to help people. . . .They said they did not know but I would be a great man because not many men were called to see such visions” (from Black Elk Speaks by John G. Neihardt and Black Elk). From then on, Black Elk dedicated his life to fulfilling this dream.

Native American Indians believe that people become sick if they fail to live out their vision, insights, and dreams. Many of the world’s indigenous cultures possess immensely deep and sophisticated understanding of what we call insight. For example, in a vision quest, an individual travels into the wilderness seeking a vision to guide them.

We all have insights into our purpose and vocation; unfortunately, modern society creates such “noise” that we sometimes fail to notice them. Throughout our educational process, we’re trained in analysis but not in intuition and dreaming. Given these constraints, is it possible to learn the conditions for creating vision? How can we access the kinds of insights that allow us to be a vehicle for breakthrough innovations?

The U-Process

We all have dreams and images that come to us. What makes Einstein and Black Elk unique is the fact that they were somehow open to the possibilities that their visions implied. I’m sure many people before Einstein had images of lightening bolts, but it took an Einstein to turn such an image into the theory of relativity.

The U-Process, developed over many years by Joseph Jaworski, Otto Scharmer, and others, operates on the belief that we can gain insight into our most intractable problems, large and small, by cultivating certain capacities and the right conditions. As illustrated by the examples of Einstein and Black Elk, these capacities and conditions are not new or unique; however, in recent times, they have been marginalized in the hyperrational West. The U-Process is an attempt to re-legitimize these capacities, to complement our rationality with non-rational ways of knowing.

The U-Process is based on a belief that there are multiple ways of coping with highly complex problems, some more successful than others. All too often, we respond to challenges by deploying solutions that we’re most familiar with; we might term this approach “reacting.” It’s a bit like being trained to use a hammer and then seeing the whole world as a nail. And, in some cases, this method is appropriate—like when building a house.

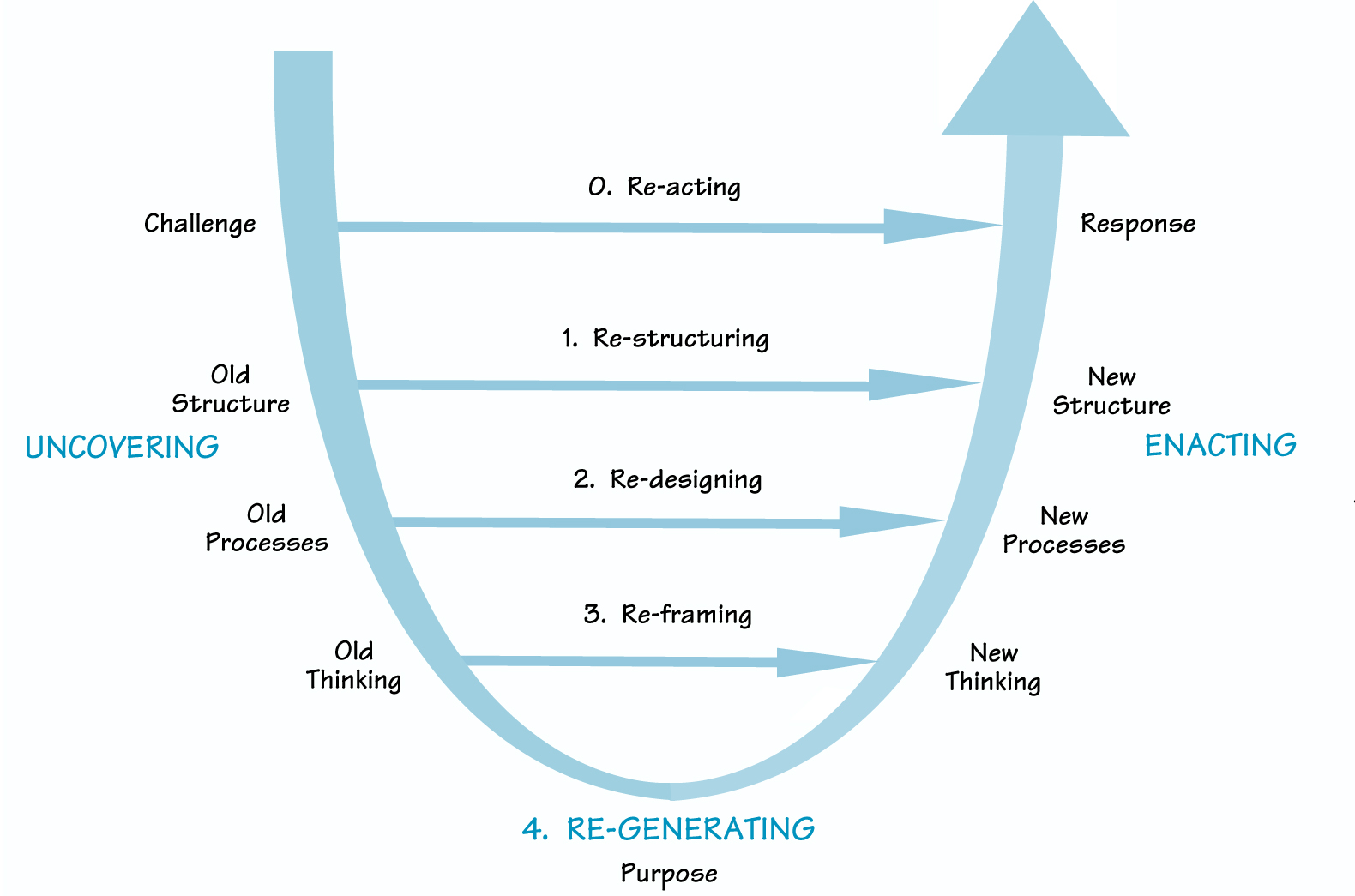

But when faced by seemingly intractable problems, we need to respond in a deeper, more thoughtful way, one that sets the stage for true insights to emerge. In these cases, nothing short of a regeneration will successfully resolve the situation (see “From Reacting to Regenerating”). The U-Process offers an understanding of what regeneration means and how to get there.

Three Phases, Seven Capacities

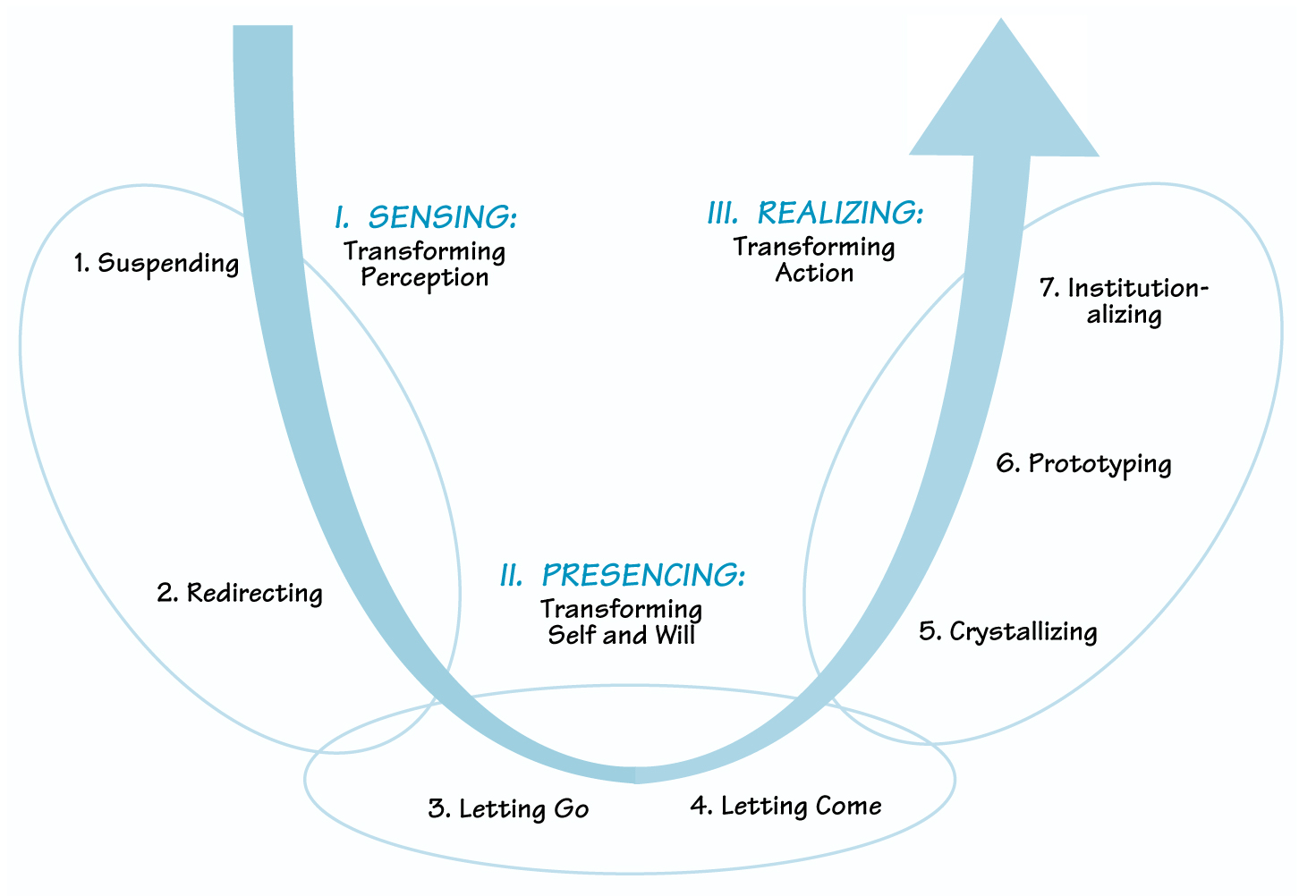

In order to create the conditions for regeneration to happen, the U-Process outlines three “phases” that involve seven “capacities.” Each of these phases—sensing, presencing, and realizing—involves the creation of a specific environment in support of a particular type of learning. So for example, sometimes we require stimulation, which might involve traveling and taking in large amounts of sensory information such as new sights, sounds, and smells. At other times, we require a quiet and reflective space in order to make sense of our inner thoughts and feelings. The physical spaces required for these two activities are very different. The U-Process involves creating three such spaces in three overlapping phases, as outlined in the following diagram (see “The U-Process” on page 4).

FROM REACTING TO REGENERATING

All too often, we respond to challenges by deploying solutions that we’re most familiar with; we might term this approach “reacting.” But when faced by seemingly intractable problems, we need to respond in a deeper, more thoughtful way, one that sets the stage for true insights to emerge. In these cases, nothing short of “regenerating” will successfully resolve the situation.

To move through these three phases, we must develop and utilize seven “capacities.” A capacity can be thought of as a skill or an ability to do something. So for example, you may be skilled at listening or at photography. As with all skills, the more you practice, the better you get. While the capacities that make up the U-Process are most commonly thought of as individual capacities, that is, something that we as individuals can learn and practice, they can also be group practices.

Sensing

Otto Scharmer, one of the architects of the U-Process, often says that a failure to see is the biggest barrier toward tackling our challenges. In the modern world, things are so complex and so fast-moving that it’s difficult to get a picture of the whole. When we don’t have a picture of the whole, we end up arguing strenuously from our position of “truth.” We’re willing to invest massive amounts of time and energy in solutions based on the assumption that what we’re seeing is a whole, when in fact it may well be a small part of the whole. The purpose of the sensing phase is to open ourselves up, uncover reality, and see the system we’re a part of.

While this might sound relatively simple, it’s difficult to do. The difficulty arises, in part, from the fact that what we see is too often colored by a lifetime of beliefs and biases. As the 12th-century Sufi Maulana Majdud put it, “In the distorting mirror of your mind, an angel can seem to have a devil’s face.”

In the book Presence, by Peter Senge, Otto Scharmer, Joseph Jaworski, and Betty Sue Flowers, the authors recount how a group of U. S. business executives from the car industry traveled to Japan in order to learn how Japanese manufacturers were keeping their production costs so low. On their return, a professor asked them what they had learned. They told him they hadn’t learned anything because the Japanese hadn’t shown them their real factories. The U. S. executives knew these factories were dummies because they didn’t contain any stock. The truth is that the Japanese had created “just-in-time” production, in which parts were brought in only as they were needed. The U. S. executives, despite being shown an innovation, could not recognize it because their own notions of manufacturing stopped them from seeing what was in front of them.

THE U-PROCESS

In order to create the conditions for regeneration to happen, the U-Process outlines three “phases” that involve the creation of specific environments in support of particular types of learning. To move through these phases, we must develop and utilize seven “capacities.”

We must develop two key capacities in order to be able to “uncover reality”: suspending judgment and redirecting. Often our judgments about things cloud our ability to see accurately. Although the U. S. executives were experienced in car manufacturing, their judgments about what constituted manufacturing fooled them. In practical terms, suspending judgment means becoming aware of your own personal lenses and biases. It doesn’t mean that you reject them but rather that you, in a sense, hang them up like you would a coat and examine them. Suspending judgment means being conscious of how and when your mental models are affecting your perceptions.

The second capacity, redirecting, is the ability to listen and see from different positions. Usually we listen and see from within ourselves. We evaluate situations and data, asking ourselves questions such as, “What do I think of this? How is this information useful to me?” So for example, if we’re interested in learning about farming and meet a farmer, redirecting could mean that we ask ourselves questions such as, “What does this information mean to him? What does he think of this situation?” We would strive to see through his eyes.

We might also examine a situation from the edge, the periphery as opposed to the center. What does a situation look like far from the action? The ability to redirect means expanding our sense of place and time. Suspending judgment is a prerequisite to redirecting. As my colleague Adam Kahane says, if we can’t suspend judgment, we end up simply projecting our own movie–our own stream of thoughts, ideas, and concerns—onto a situation rather than shining a light on it.

Presencing

In the sensing phase, we uncover the current reality of the system as a whole. In the presencing phase, we uncover our deeper knowing about what is going on in the system, our role within it, and what we, individually and collectively, are being called upon to do.

Most of us are trained to objectify problems as something separate and distinct from us. In doing so, we forget that we are an active part of the systems we’re trying to change. It’s impossible to grasp the system as a whole without considering our own relationships to it and opening ourselves up to the question of what this whole is demanding of us.

This engagement is normally difficult to practice within our day-to-day lives because we live in environments in which much of our stimuli are mediated through manmade features. From architecture to television, these environments have been designed to provoke specific responses and feelings within us. These responses dilute our inner knowledge.

The first capacity of presencing is letting go. When confronted with a challenge, we often have our favorite theories, tools, and ideas about what is needed. We often believe, sometimes subconsciously, that if others had adopted our positions or solutions, then everything would be fine. The practice of letting go is an act of releasing all these things. It’s about giving up and surrendering to whatever it is that might want to emerge. It’s about putting ourselves into a state of profound openness.

Such actions take courage. We cling to our ideas and notions because they orientate us and tell us who we are and what we’re supposed to do. Letting go, in a very practical sense, means leaving the shores of our certainty. It means overcoming our fear of the unknown. We often need to let go of something for something new to be born.

The second capacity of presencing is letting come. While the phrase “letting come” seems passive, the act of giving birth can be extremely demanding and painful. Letting come is a uniquely difficult point in the U-Process, because it represents a shift to action, and all action is a commitment of some sort. If we think of the process as the birth of new ideas and a new understanding of our vocation, then our role is to act as mother, midwife, and witness at the same time.

One activity that supports the presencing phase is spending time alone in nature. According to Senge et al., being outdoors helps us think and see in new ways. When we’re in nature, we’re able to step outside of ourselves and see ourselves as part of a larger whole. Somewhat paradoxically, we do so in order to listen to our innermost voices.

Presencing can happen under a number of conditions and in a number of ways. I would describe it as the space between waking and dreaming, where your mind is floating free. Sometimes I might enter this state with a problem in mind, but not always. In presencing, I’m not consciously directing my thoughts. Since I started becoming aware of this experience, I’ve been able to access it more and more consistently. When I’m trying to write and it isn’t working, I often find that it helps to calm myself down, slow my breathing, and enter into what I used to call a space of “zoning.”

The act of presencing isn’t the same as “taking a break,” so when we fall asleep, we’re not presencing. The act of presencing embodies intentionality.

Finally, it would be a mistake to think that presencing is about making a choice among different options. Rather, it’s about arriving at the place where it’s blindingly clear what an individual or group must do. Then the only choice is saying yes or no. Presencing is about arriving at a deep knowing and profound clarity as to what the following course of action must be.

Realizing

Realizing is the phase of multiple, rapid conclusions that unfold over time. In the U-Process, we enter the realizing phase with clarity about what we need to do next. We usually don’t know exactly where this action is going to take us, but we know what the next steps are and in what direction to take them. We have a picture in our minds of what we want to create. We may not be able to see all the tiny details of the picture, but nonetheless we have a real sense of its broad details, shapes, and colors. We call this capacity crystallizing.

My experience of realizing, typically when I write, is that I don’t stop and ponder, but instead I enter into this strange state of being driven by my vision. I trust that, if I just let my hand go, it will move on its own accord and produce whatever needs to be produced. I need to get out of the way of whatever action is trying to emerge. If I put myself in between my hand and my insight, then I’ll falter and become confused.

There are at least two approaches to producing something new, be it a sculpture or a piece of software. The first is by going through a long and detailed planning process. We try to anticipate and design for as many different scenarios as possible and put the whole plan on paper before taking the first step. This is how modern planning processes usually work.

The U-Process, however, has a different way of approaching the realization of new ideas that involves creating quick, incomplete models that you can physically work with. Instead of planning and designing, you just start. You take the first step as quickly as possible. You try something out and then evaluate it. You walk around it, test it, and then change it. This capacity is known as prototyping. One of the most powerful ideas behind such an approach is to “fail often, fail early.” By making many small mistakes early in the process rather than a single catastrophic one further along, we go through a repeated learning cycle.

An artist friend of mine once recounted how this approach works for him. Every morning, he wakes up and goes to his studio, where he looks at the work he’s done the night before. He then goes for a quiet walk in the woods. When he comes back, he starts working. By doing so, he clarifies and uncovers a new aspect of the picture.

This cycle can continue for a long time. In the case of an Einstein or Black Elk, it’s the work of a lifetime to excavate the details and nurture the seed. The approach, then, is one of cultivation and not of a single grand, heroic act.

Institutionalizing, for me is a complex word. In working with the U-Process and with the idea of social innovation, I have found very little research about how social innovation spreads across our societies. How, for example, did the practice of surgeons washing hands spread? What is the theory behind such a spread? How do deep-rooted cultural practices change? How does a practice common among a small group of people become common practice among millions of people? In contrast, there are well-understood models for how technical innovation spreads.

When considering the context of modern institutions, the idea of institutionalizing raises deep questions about how our institutions change. While the field of organizational development addresses such questions, I find the ability to shift the complex cultures of organizations more a black art than a science. The plethora of approaches that consultants advocate indicates that we are still enmeshed in competing schools of thought, and a clear paradigm for how such work should be done has yet to emerge.

The capacity, then, of institutionalizing raises more questions for me than it answers. I do not see it as an individual capacity but rather as a process in itself that requires a lot of work and research in order to be understood.

, “Hardwired to the Cosmos”

“And then she saw it. She could not say what it is she saw, staring at the cubicle door, there was no shape, no form, no words or theorems. But it was there, whole and unimaginably beautiful. It was simple. It was so simple. Lisa Durnau burst from the cubicle, rushed to the Paperchase store, bought a pad and a big marker. Then she ran for her train. She never made it. Somewhere between the fifth and sixth carriages, it hit her like lightening. She knew exactly what she had to do. She knelt sobbing on the platform while her shaking hands tried to jam down equations. Ideas poured through her. She was hardwired to the cosmos.”

Last August, I went on a writing retreat. I had to produce the first draft of a fieldbook bringing together Generon’s learnings about the U-Process. I knew a peaceful place in the countryside, run by some friends. It sounded ideal. One bright summer day, I packed my bags and boarded a train. I had a bag bulging with reference books, papers, and six months of notes. Stretching out before me were two weeks of working without disturbances. Everything was perfect, right? Not quite.

Up to the point where I found myself facing an empty page, all my thoughts had been on creating the right physical conditions for my task. But once I arrived at my destination, I didn’t know where to start. I looked at the page helplessly. I looked at the masses of books and papers and notes that I had spread around me. I looked out the window onto the valley below. It started raining. For two days, I tried to start and couldn’t. It wasn’t writer’s block—I just didn’t know what to write. I was on the edge of panic, counting down the days I had left. It seemed like a very short time. I knew I couldn’t turn up after two weeks without having a draft. I simply couldn’t figure out how to start.

On the morning of the third day, I realized that I had a process right under my nose that could help: the U-Process. I sketched out a schedule: four days of sensing, a weekend of presencing, and roughly five days of realizing. However, that would mean not putting pen to paper for six whole days. Eight days, counting the two that had just passed. I would have five days to write the entire draft. It seemed like a big risk, but I decided that I had to take it.

I spent four days reading. I then went into the nearest town for a two-day weekend retreat. I came back and wrote the first draft. I went home a day early.

As my experience shows, apply-ing the U-Process at least at the individual level—need not be a complex procedure. It can be practiced by anybody. Take any creative task (that is, a task where something needs to be created). The sensing phase involves “seeing” the situation, the problem, the material that you have to work with. It’s a process of immersion into the world of the task. If you’re going to work, for example, with fabric, then immerse yourself in understanding it feeling, touching, smelling, and “becoming one” with it—and for that matter everything else related to your task.

NEXT STEPS

Reread the section “Hardwired to the Cosmos,” about Zaid’s experience with applying the U-Process to his writing project. Are you faced with a complex problem or a creative task that would benefit from a new level of thought and action? If so, follow Zaid’s tips for moving through the U-Process.

- Sketch out a timetable for completing the sensing, presencing, and realizing phases.

- Line up a learning partner—someone you can turn to as a sounding board and who can turn to you, too.

- Move through the phases, using the seven capacities—suspending, redirecting, letting go, letting come, crystallizing, prototyping, and institutionalizing. Each of the capacities exercises a different “muscle”; you’ll undoubtedly find some more challenging than others.

- If you get stuck, follow the lead of Zaid’s artist friend and go for a quiet walk.

- Finally, trust the process and be gentle with yourself. Opening ourselves to new ways of operating requires a great deal of stretching and learning as well as a lot of courage. Give yourself credit for your willingness to go deeper, and celebrate your successes.

If you’re trying to create public policy, then immerse yourself in the context of the policy. Whose idea was it? Why is it needed? Who will it impact? Who thinks it’s a bad idea? Who thinks it’s a good idea? Has something like this been done before? Where? What happened?

The idea of “connecting to source” emerges from considering what it means to presence. If we take the example of an Einstein or a Black Elk, or the description that Ian MacDonald provides at the start of this section, it is easy to see how the idea might be considered mystical or esoteric. Our work with the U-Process, however, is making the pragmatic case that we know something about how to increase the probability that such insights occur. In doing so, the poetic phrase “connecting to source” alludes to the idea that our insights, be they about a specific system or the nature of reality as a whole, come from some source. I leave it to you to consider what the nature of this source may be. Suffice to say, I believe it’s a rich area of inquiry, and one that we should not shy away from.

The presencing phase is an intensely personal experience that depends on our individual needs. What do we need in order to hear ourselves clearly? For a master practitioner, presencing means being able to be silent at will amid the babble of inner voices and thoughts that normally fill our heads. From this space of silence, a deep inner knowing emerges.

Many of us are not adept at achieving silence and being comfortable with the legitimacy of what emerges from it. In these cases, we must do what we can, use whatever methods we know, and generally start where we are. At Generon, we take groups of people into nature where they spend an extended period of time alone, listening to themselves. Meditation techniques can also be helpful.

Individuals may even try something more familiar, like watching a movie or listening to music. Often when we watch a slow movie or listen to a piece of music that touches us emotionally, we enter a contemplative state where we start to reflect on our own inner landscape. This space of quiet and contemplation gives us a taste of what it means to presence.

The shift from presencing to realizing is simultaneously gentle and fast. It comes as an explosion of energy as we finally allow our ideas to meet the material world, to take form. We pick up our pen, laptop, or hammer and simply start to work, trusting in what will come. In the first moments of shifting from presencing to realizing, we don’t reject anything. This is not yet a space for the rational mind. There will be plenty of time later for logically sorting and pruning. Instead, this is a time for your hands to create whatever they will.

The key barrier when working with groups is a lack of trust: within each individual, across the group, and in the process. If group members don’t know each other, then they must build trust so that individuals feel they can take the risk of being open. The degree of difficulty in building trust within a group is a function of how much individuals trust themselves. And participants must have faith in the possibilities inherent to the process that they are about to embark on.

Point of Departure

In this article, I have outlined my current understanding of the U-Process. I have not provided a detailed prescription for how it works because I do not want to preclude or close down avenues of experimentation. I invite you to make this process your own. Ultimately, the journey the U-Process invites us on is about creation. There can never be an instruction manual for creation, at least no more than there can be an instruction manual for art or living in general—there are only points of departure. This is a journey where we experience the intense drama of bringing something new into the world. In doing so we remember that we are joyously and forever “hardwired to the cosmos.”

Zaid Hassan (hassan@generonconsulting.com) works at Generon Consulting and is a Pioneers of Change Associate.

Copyright © 2006 Zaid Hassan (A version of this article was first published in the Expressions Annual 2006, Nashik, India.)