The “learning organization” is fast becoming a corporate buzzword. Many companies are jumping on the bandwagon without really understanding what a learning organization is, or what it takes to become one. There is a serious risk that it may become yet another management fad.

The “1992 Systems Thinking in Action Conference: Creating Learning Organizations” made a statement that creating learning organizations is a long-term process of fundamental change. The 600-plus participants showed their commitment to that journey through their enthusiastic involvement throughout the 27, days. Over 30 concurrent sessions helped add details and richness to the central theme, providing people with the opportunity to learn new tools and techniques as well as share their experiences putting those ideas into practice.

Each of the three keynote speakers provided a different perspective on what it means to create a learning organization. The following pages contain excerpts from their talks, which helped paint, in broad brushstrokes, the essence of what is needed to build learning organizations.

—DHK

“Acknowledging the collective nature of our perceptions marks the first step in the journey toward becoming a learning organization because the way we perceive the world is absolutely critical to all learning processes.”

PETER SENGE – A CRISIS OF PERCEPTION

Peter Senge’s talk, “A Crisis of Perception,” cut deep into our shared pool of assumptions. In a real sense, we are our assumptions because we perceive the world through the distinctions we make. But those distinctions do not originate from us as individuals; we inherit them through culture. Corporate paradigms and sacred cows are part of the “inherited” assumptions that affect how we perceive the world. Acknowledging the collective nature of our perceptions marks the first step in the journey toward becoming a learning organization because the way we perceive the world is absolutely critical to all learning processes.

We, as a species, have been evolutionarily programmed to be acutely aware of sudden, dramatic changes in our environment. There’s a very simple reason for that: for virtually all of our history, those were the primary threats to our survival.

The problem is that our world has changed and we have not. Today, all the primary threats to our survival come from slow, gradual processes, but we’re still waiting for sudden events. One way to think about this dilemma is as a crisis of perception. It is as if we are driving down a dark road and at the same time we are accelerating, we’re also turning down the headlights. Our power, our prowess, is causing the acceleration. Our diminishing capacity to see what’s around us is dimming the headlights. But as we accelerate, we really need an even greater capability to see into the future. That is, as our power increases, our perceptiveness also needs to increase…

Fundamental Assumptions

To address this crisis, we have to begin by exploring this question: what do we mean by perception? A common notion of perception is that we’re here and the world is out there. We don’t see it perfectly, since it’s very complex, so we filter, abstract, and process it. This view of perception is based on two assumptions: that there is an external reality, and that we can say something intelligent about its intrinsic nature, independent of our interaction with it.

There are a couple of problems with this common notion of perception. First, it’s rooted in assumptions. Secondly, progress in the field of understanding the biology of perception is beginning to show that it is an untenable viewpoint…

The reason we have this love affair with this simple model of an external world is that it suggests a basis of certainty. We have a deep love of certainty. It starts our whole cognitive process off with an external point of reference — the reality that is out there. What we need to do is give up the belief that there is absolutely, intrinsically, an external reality.

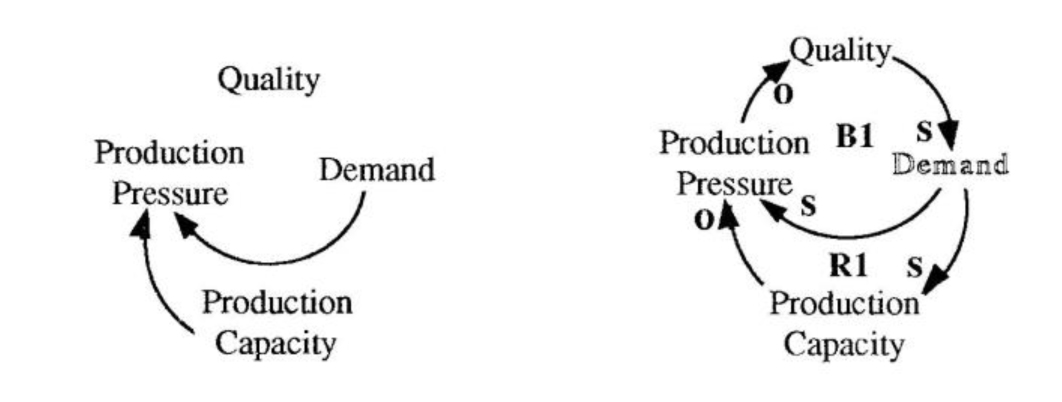

Causal Loop Diagrams--A Tool of Perception

Rather than thinking about a causal loop diagram as either a description of the way the world really is, or a forecast of the future, we can actually begin to think of it as a tool of perception — a way of seeing certain things we otherwise might not see.

For example, say our company is experiencing an increase in demand and we don’t have enough capacity to meet it. Without the linguistic distinction of a feedback loop, many people see a world where if demand rises and production capacity is out of line, we have problems (left diagram). Some may or may not see the connection to quality. Some may or may not see the connection from quality to demand. Many do not even think in terms of the whole unit. In this worldview, when you eventually find yourself with falling demand, you blame the fickle customers or attribute it to tough competitors.

However, if we recognize the language of systems thinking and its set of linguistic distinctions, we might draw a link between demand and production capacity (right diagram). That is, we add capacity based on demand. But there’s usually a long delay in acquiring capacity so by the time capacity comes on line, the continued production pressure has led to lower quality and a loss of customers.

By comparing these two diagrams we can see that, depending on what worldview we choose, we construct a whole different set of perceptions.

Perceiving through Our Distinctions

We perceive the world by making distinctions — but where do those distinctions come from? That is the territory of culture, because by and large, how we make distinctions is inherited. Our perceptions are collective, not individual. To a much higher degree than we recognize, we, collectively, are the perceiving apparatus, not I.

So what might be some of the implications? One implication is that it will begin to shift the perceptual center of gravity in our culture. Right now that center has shifted to the extreme of events and short-term orientation. The practical question is, what can we be doing to shift that perceptual center of gravity? (See “Causal Loop Diagrams—A Tool of Perception.)

Forecast vs. Prediction

Several years ago my friend Pierre Wack, the man who developed the scenario planning process at Royal Dutch Shell, was telling me an interesting story that highlighted the difference between prediction and forecasting. He had lived in India for much of his life, and he told me that if it rains for seven days in the foothills of the Himalayas, you can predict the Ganges will flood.

Now, it’s not the rain that causes the flooding, but the intermediating structure. If it rained for seven days in the middle of a tropical rain forest, there would be no flood. It’s the structure of the network of rivers, the absorbency of the ground, and the waters flowing through that create flood conditions. Relating that to forecasting versus prediction, Pierre explained, “A forecast is an attempt to get some quantitative information about the future. A prediction, however, is an understanding of certain predetermined consequences. You don’t know exactly when they’ll happen, you don’t know exactly how strong they’ll be. But you have some appreciation of an underlying phenomenon….”

Proprioception of Thought

If you close your eyes and raise your hand, you are aware your arm is upraised. When you close your eyes, you know where your body is. That phenomenon is called “proprioception,” and it is linked to one particular part of the brain. If that part of the brain is damaged, you have to learn to use visual cues to control your body, because you are no longer conscious of your body movements.

It appears we have no proprioception regarding our thoughts — we just have them. Our perceptions just occur to us. If we’re really trying to create a whole new domain of behavior, actions, and possibilities, but our perceptual apparatus is dysfunctional, then we have to become conscious about it. We have to become proprioceptive of our thought and our perception…

Seeing into the future is not about our eyes. The capacity to expand our time frame is not about what we can see; it’s about the distinctions we make and the way we think. We need to be able to speed up time in a way that allows everybody to see it. We need to be able to see into the future and extend our time horizon, by virtue of the distinctions we invoke. Maybe the whole purpose of this systems thinking stuff is nothing but expanding our capacity for perception…

Dialogue

Our perceptions may be vastly more collective than we think. The work that’s going on today in the area of dialogue is looking at this issue very directly. In dialogue, as we’re starting to understand it, we begin to probe into the cultural creation of meaning.

The exploration into dialogue is clearly in the right area, because it looks at the generative process whereby we invent cultural distinctions collectively. This is not an individual job. This is us, not me, not I…

One thing I keep coming back to, as a deep, deep, personal cornerstone in the changes that have to be made, is this business about certainty. There is something in all of us that loves certainty. And my own experience in watching others is that one of the things that may be the hardest to give up is that rigid external point of reference — what is it really?…

RUSSELL ACKOFF — ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING AND BEYOND

If our old ways of perceiving the world are dysfunctional, then the institutions and structures that are a product of those perceptions need to be reviewed and redesigned. Russell Ackoff presented a different kind of organizational structure that is more closely aligned with the democratic ideals that govern the way we operate as a nation. He proposes a circular design where hierarchy is not just top-down but bottom-up as well. Every system has essential properties which none of its parts have. If I bring an automobile into this room and take it apart, I no longer have an automobile. The reason is that an automobile is not the sum of its parts — it’s the product of their interactions. The same thing is true in business. Business schools offer courses in production management, finance, accounting, marketing, etc. They take the organization and business apart. The assumption is that if you know how to run each part, you can then put them together into a well-run whole. But there’s a fundamental principle in the system of science that can be rigorously proven — if every part of a system operates optimally, the whole cannot operate optimally.

Effective management has to be the management of the interactions of the parts, not of the parts taken separately. Divide and conquer is no longer an effective strategy for management. How, then, can we organize in order to manage interactions? To do so, we need to understand a fundamental difference between “power over” and “power to.” “Power over” is the ability to exercise authority — to punish and reward. When you have a well-educated workforce, you can’t get things done by exercising power over them. There’s a negative correlation between “power over” and the rising education of subordinates. We can no longer get things done in our organizations by exercising power over people…

Democracy and Hierarchy

The solution, then, is to democratize organizations. Now, this appears to raise a paradox. Hierarchy is essential for the organization and coordination of work. But hierarchy and democracy are inimical. You cannot have a democratic hierarchy, because hierarchy is inherently autocratic, right? Wrong. Absolutely wrong.

There is nothing under the meaning of organization which requires that we represent it in two dimensions — levels of authority that flow up and down and responsibility that flows right and left. It’s just a convention. And because we haven’t been able to see organization in more than two dimensions, we have not been able to see how to develop a democratic hierarchy….

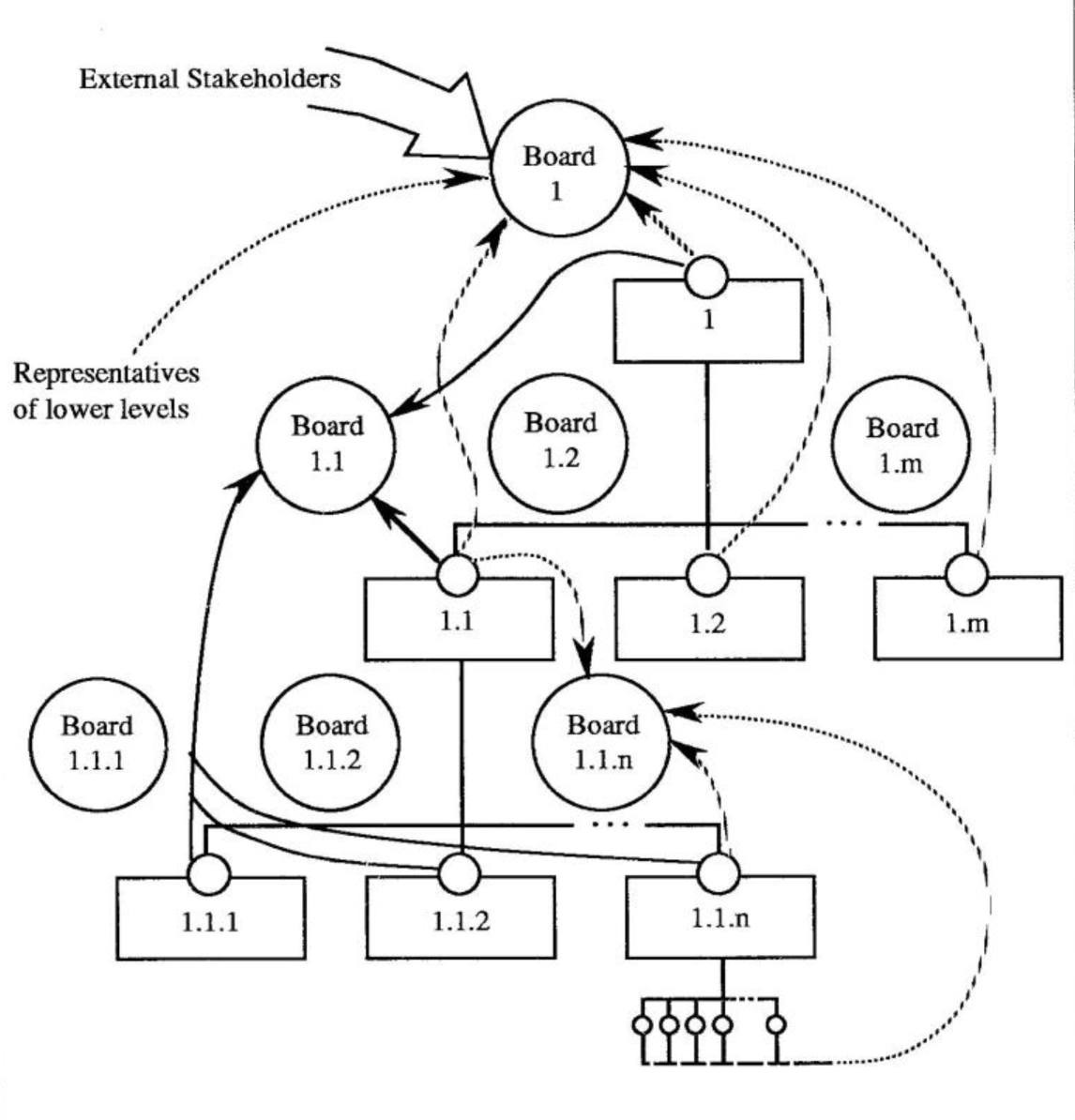

The Circular Organization

There is such a thing as a democratic hierarchy — the circular organization. The essential idea in the design of a circular organization is the creation of a board. Since the board of directors is considered to be a good idea for the chief executive, why should we deprive every other manager of having a board? So every manager has a board which will consist of himself, his immediate superior, and his immediate subordinates (see “The Circular Organization”). This promotes interaction within the organization, because each manager interacts with five levels of management — two levels up, two levels down, and across at his own level. In most organizations you don’t have that kind of an opportunity.

At the very bottom of the organization, the work groups should be small enough so every employee of the organization has the opportunity to serve on the board of his boss. Also, no group on the board should be larger than the number of subordinates. The subordinates do not have to be the majority, but they ought to be the largest single group on the board…

Now what do the boards do? They have six functions. First, the board produces plans for the unit for which it is the board. Secondly, they establish policy — they set up the rules that govern decisions. The third function is the board is responsible for coordinating the activity of the level below it. This way, coordination, or horizontal interactions, are in the hands of the people who are being coordinated (with the participation of the two higher levels of management).

The fourth responsibility of the board is integration. Because of the vertical integration of the circular organization, no board can pass a plan or a policy which is incompatible with a higher level. This eliminates a lot of problems, since 50% of the problems managers face are created by managers at some other level of the same organization. Why? Because decisions that are perfectly sensible at one level of the organization can often be disastrous three or four levels down.

The fifth function of the board is it makes the quality of work life decisions for the members of the board. The sixth function is the most critical one: they evaluate the performance of the manager whose board it is, and are responsible for helping him increase his effectiveness.

No manager can hold his position without the approval of his board. That’s what makes it a democracy and not an autocracy. Nobody can be in a position of authority over others without the others collectively having authority over him or her. So you get circularity. That’s why it’s called a circular organization…

The Circular Organization

Traditional Management

There are fundamentally three traditional kinds of management. One is the kind that says, “The current situation is intolerable, and things are getting worse. I wish things were like they used to be.” Their primary function is to recreate the past. This type of management is called reactive. It’s “reacting” — acting back, going back to a previous state.

A second way of dealing with problems is to forecast the future, decide where we want to be in that forecast, and plan a path from where we are now out to the realization of our vision. The problem is that the path lies through a future that is out of our control to forecast. That’s called proactive, as opposed to reactive.

The third position is inactive. These are people who say, “Well, the world may not be perfect, but it’s good enough. Let well enough alone. Don’t rock the boat. Let nature take its course.” So their principle objective is to do nothing.

Occasionally, the people who are trying to make things better, and who, in the eyes of the inactive manager, arc responsible for all the problems, sometimes create a problem which threatens the survival or stability of the inactive’s organization. Now the manager has to react to the crisis, so he practices crisis management. That means he’s always active, because with an increasing rate of change in the environment, the intensity and number of crises increases.

But the inactive manager would be busy even if there were no crises. Why? Because people don’t like doing nothing — being inactive. They have to do something. And therefore, the inactive manager’s principle concern is, “How do I keep people busy doing nothing?” This creates bureaucracies…

Corporate Perestroika

In almost every organization, the service units are bureaucratic monopolies. Why? They’re subsidized from headquarters through a budget that’s allotted to them, and their users do not pay for the services or products they receive. Their users have no choice as to where they get their accounting, or their advertising, or their research and development. They have to use the internal source. And the internal sources have no choice in to whom they supply their service. So we get bureaucratic monopolies…

Companies don’t operate under the market economy. In fact, they operate with an economy which is identical to the economy that the Soviet Union had before it recently reorganized. So what I’m describing is corporate perestroika. Just as what I just finished talking about was corporate glasnost, or the democratization of the corporation.

What happens if we introduce the market economy within rums as well as between firms? The essential characteristic of that new system is this: every unit in the organization whose output is consumed by more than one customer or consumer will be a profit center. That does not mean profitability will be the measure of its performance — but it will be taken into account in evaluating its performance. And, subject to a few constraints, every unit will have the following freedoms: it can sell its output to whomever it wants (internally or externally) at whatever price it wants to sell it; and it can buy what it wants anywhere it wants to at whatever price it’s willing to pay…

Learning

You never learn anything from doing something right. Because if you do something right, you already know how to do it. So, all you get is confirmation or affirmation of what you already know. You only learn from mistakes — that’s obvious, right? What is not obvious is that almost every organization — public or private, for-profit, or not-for-profit — is designed to conceal mistakes, particularly from those who make them. As a result, they can’t learn. Because if you don’t know what mistakes you make, there’s no way you can improve.

How do we design a system which will make people aware of their mistakes without acting as a policeman and punishing them for errors? August Busch, at Anheuser Busch, one of the best corporate executives I’ve known, had a very simple saying for his executives: “If you don’t make a mistake this year, there’s something wrong with you because it means you’re not trying anything new. But you better not make the same mistake twice.” Now, that’s the right kind of a rule to have. You want a system which allows you to make errors but enables you not to make the same error twice — a system that deals with learning not only skills and information, but gaining understanding and hopefully even wisdom…

“Almost every organization—public or private, for-profit, or not for-profit—is designed to conceal mistakes, particularly from those who make them. As a result, they can’t learn. Because if you don’t know what mistakes you make, there’s no way you can improve.”

SUE MILLER HURST — COME TO THE EDGE

Designing and implementing new structures will not fully transform an organization if the people do not release themselves from the old internal structures that say “1 can’t,” or “I am not worthy.” Sue Miller Hurst spoke to the learner inside each of us, talking about challenging our assumptions about our limitations and then breaking through them. Creating a learning organization requires a community of learners — and if we do not believe in our capacity to learn, then we cannot help create the space in which learning thrives. One of my favorite poems is by St. Appollonaire: “‘Come to the edge,’ he said. They said, ‘We are afraid.’ ‘Come to the edge.’ They came, he pushed them, and they flew.”

Eric Hoffer has said “in a time of drastic change, it is the learners who inherit the future. The learned find themselves equipped to live in a world that no longer exists.” One of the possible questions for us today, while we’ve been so diligent about our learning, is in what way have we followed the path of the learned instead of the path of the new learner? Imagine or remember if you can when you were a little child, when the beginner’s mind was not something you had to put on, but actually was something you lived through and in. Think about the child in you, still present. You are a marvel. You are unique. In all the world, there is no other child exactly like you. In the millions of years that have passed, there has never been another child like you.

We come as children, and when we come we really ask of life to be nurtured, to be loved, to be inspired. And we ask of life to notice us and to feel that we’re a gift. We come, each of us precious, fragile and very, very unique. And as we come, we come with the highest of hopes. And it’s the possibilities I want to talk to you about today…

Breakthrough — Moving to “I Can”

I want to talk to you about breakthrough. I have a sense that we’re wiser than we know or we’ve claimed. Over the last decade, over the last millennia, we have actually discovered much. But it seems as if it sometimes sits “out there” as interesting stuff. Somehow it’s hard to take it in and really act like we know it from the place of behavior instead of the place of intellect.

Remember Nobel Prize winner Ilya Prigogene, who was looking at the second law of thermodynamics and questioning whether the universe actually does run down in energy? He won the Nobel Prize for his work with dissipative structures. The interesting part is that he talked about how organisms under enough stress and perturbation actually fall apart and fall back together at a higher level of organization. The more complex the organism, the more easy it is to actually disrupt it so it will fall apart and fall back, fall apart and fall back—except that with human organisms we get the choice, do we want to fall back together or just leave it?

“If we are so rich in potential, what bars the door to our wisdom? To our collective action?…Maybe our skills and knowledge are the means for becoming acquainted and reacquainted again and again with our infinite capacity…”

When we look at the work of other pioneers — Karl Pribram, Rupert Sheldrake, Roger Sperry, Lyall Watson, Howard Gardner, or the ground-breaking work of Lazonov, Bell, Pert, Borysenko, David Bohm, Robert Rosenthal, Marian Diamond — we can see we have learned much about the human mind, the uncertainty of our sciences, and the holographic nature of memory. We can sense the limitlessness of our human capacity and the limits of our current working models of life. If we are so rich in potential, what bars the door to our wisdom? To our collective action?…

Remember the AIDS quilt? One of the quilts said, “If we are made in the image of our maker, then we are not human beings having a spiritual experience; we are spiritual beings have a human experience.” I want to invite us to the beginner’s mind that suggests maybe we are not using our learning capacity to gain the skills and knowledge we need. Maybe it’s the reverse — maybe the skills and knowledge are the means for becoming acquainted and reacquainted again and again with our infinite capacity…

Attention as Leverage

What really is the leverage for opening up to wisdom? Maybe it’s as simple as our attention. What do you want to pay attention to, right here, right now? When there’s disharmony between us — when I forget to think of the system, when I’m blaming and accusing, when I’m feeling like a hero, when I’m feeling like a victim, when I can’t figure my way out — what would happen if we just focused our attention? What if I actually honed all this ability — not of the brain but of the mind — right to this one point of attention? I actually think whole changes would be made on the planet, one by one by one…

I’d like to call you to a different action than some might do: I want you to make all the organizational changes you can think of that will make things more democratic, that will actually give people a voice, that will actually honor their being. I want us to reform and rethink and redesign factories. In fact, let’s call them design shops instead of factories. That way we can be free to place the furniture and the people differently so we might really empower people to come to work in a way that the soul comes to work. And then I want to empower you to stand in a place in 1993 that maybe you never stood before. This group here today can actually be the momentum of a wide change, coming not so much because we knew we had to fix it, but because we knew we could help — that we could hold the possibility and call on others to join in. Now that’s a beautiful possibility, and it’s a journey I think we’re getting ready for.

Carlos Cassanada would have called this a “cubic centimeter of chance,” and I think it’s worth taking. As we touch the web of each other’s lives, and the web of something much deeper than we can understand right now, if we can hold each other in a place of that mystery and that caring, I think it might come into being…

In the opening speech, Peter Senge stripped away the veil of unsurfaced assumptions and challenged us to examine the very nature of reality. To address the major crises we face today, we cannot learn what we need to learn without extending our perceptive capabilities beyond the short time horizons to which we are accustomed. Russ Ackoff described alternative models of an organization that can take us further in helping us break through the dualities that bind us in our dilemmas. Sue Miller Hurst challenged us to look deep inside ourselves and recognize the eternal learner in all of us that can set our spirits free. And it is that spirit that will bring life to this thing we call a learning organization.

—Edited by Daniel H. Kim