Imagine the following scenario: I go to my grocery store and buy a dozen cans of tuna. I tell the cashier, “I’m stocking up in case things get a little crazy at the end of the year because of Y2K.” She later mentions our encounter to a few other customers and picks up a case of canned soup after her shift is over—just in case. Soon, others are stockpiling supplies as well. After a week or so, our local stores begin to run low on certain staples (see “Perception of Scarcity”).

PRECEPTION OF SCARCITY

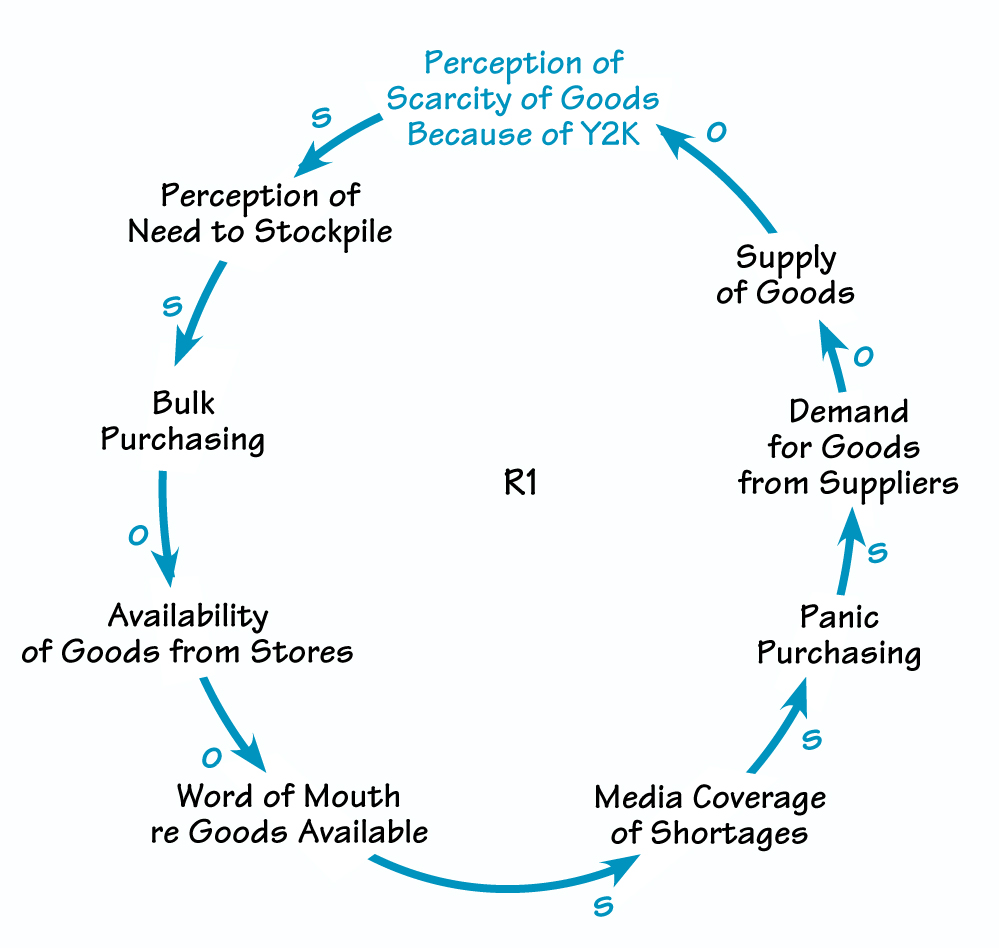

As people begin to worry about the possible effects of Y2K on the supply of goods, they feel the need to stockpile. Media coverage eventually causes panic purchasing and an increased demand for goods, which actually does lower the supply of goods while further raising the perception of scarcity.

Panic and Hoarding

Is this scenario possible? Well, to some extent, it’s already happening. Camping stores report that they have sold their entire inventory of freeze-dried foods, and their suppliers are tapped out as well. Equipment retailers are maintaining lists of people willing to pay a premium for hard-to-find gas-powered generators to keep their electricity running in case the utilities cease functioning at the turn of the year.

Where have we seen this dynamic of panic, hoarding, and scarcity before? Think back to the run on banks during the Great Depression in the United States and to the Oil Crisis of the 1970s. What actually precipitated these events was people’s fear of running out of a resource, not an actual scarcity of the resource itself. For instance, during the Oil Crisis, when less gasoline was available to the public than before the oil embargo, people kept their tanks as close to full as possible “just in case.” In response, to reduce lines at the pumps and service as many folks as possible, most gas stations limited the amount that customers could buy at one time. But this policy actually caused more panic and even greater demand.

What About Y2K?

If retailers institute similar rationing policies between now and the end of the year, our behavior around the threat of the Y2K bug may cause worse problems than the bug itself. So, what steps can we take to avoid a cycle of panic and hoarding? To start, some businesses have already increased their production runs in anticipation of a jump in demand. In addition, banks are planning to keep more cash on hand, knowing that people may withdraw larger sums of money than usual from their accounts.

Public education is another leverage point. Many banks and utilities have sent letters to customers stating that they are Y2K compliant. The media could also help alleviate people’s worries by highlighting when major computer systems, such as the air traffic control network, successfully pass Y2K testing.

On an individual level, do what you need to do now to feel comfortable about Y2K—whether it means buying extra food or having addtional cash on hand. The earlier people take such actions, the better the system as a whole will be able to handle the rush on products and services. But, whatever you do, save me some canned tuna—I haven’t finished stocking up yet!

William Latshaw is a consultant for Innovation Associates’ systems thinking and change management efforts and a global knowledge steward for Arthur D. Little’s Organization Practice