As members of communities and organizations, many people feel their days (and their energy!) being consumed by contentious conflicts between diverse stakeholder groups. Organizations must decide whether to invest in either new capacity or a new product line. Or they may have to hash out which department they can do without. Communities must decide whether to renovate an old neighborhood school or build a new school on the outskirts of town. Or they may be engaged in increasingly divisive and confusing issues around race and race relations.

But although such problems may seem intractable, there is a creative power underlying most conflicts that, if tapped, can energize a group, community, nation, or even the world, as people work collaboratively to improve their situation. By focusing not on the symptoms but on the roots of problems, people can transform deep conflicts into opportunities for participatory and systemic change. By envisioning a different future, they can change conflict from being a barrier to hope and a cause of hurt into a doorway to healing and fulfillment of mutual needs.

Beginning in early 2001, groups in Cincinnati began to successfully apply participatory tools for engaging conflict and transforming an intensely emotional debate about racial profiling into systemwide change. After a six month process of visioning and consensus-building, representatives from various stakeholder groups reached agreement on a five-point platform for change. This platform in turn served as the foundation for a collaborative settlement agreement that launched a new era in police-community relations in the city by marrying ongoing community participation with structural reforms. This model will be studied and replicated throughout the U. S. for years to come. We’ll describe what was learned during the process, what worked and what can be improved, and how you can adapt a similar approach to situations within your communities and organizations. We rely on a systems thinking approach to shed light on the process and describe the benefits of integrating simulation modeling into efforts to resolve seemingly impenetrable clashes.

The Cincinnati Collaborative

In 1999, Bomani Tyehimba, an African-American businessman from the west side of Cincinnati, claimed that two police officers had violated his civil rights by handcuffing him and unjustifiably pointing a gun at his head during a traffic stop. Then in November 2000, an African-American man suffocated while in police custody after being arrested in a gas station parking lot. These events led the Ohio chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union to join forces with the Cincinnati Black United Front and Bomani Tyehimba to file a class-action lawsuit against the Cincinnati Police Department. The suit alleged that the department had treated African-American citizens differently than other racial groups for more than 30 years. Through this action, the petitioners hoped that a judge would issue a court order or a consent decree that would force the Cincinnati police to change the way they conducted internal investigations and would mandate that they collect data about the handling of traffic stops and other incidents.

The federal judge assigned to the case, Susan Dlott, did not believe that traditional litigation was the answer to the problems of alleged racial profiling. In her view, court action would only further polarize the parties and would not solve the social issues underlying the police-community conflict. Through Judge Dlott’s efforts, all parties eventually agreed to set aside normal litigation and instead pursue an alternative path of collaborative problem solving and negotiation. In April 2001, Jay Rothman was retained as special master to the court to help mediate and guide the parties along this new path.

Jay began holding regular meetings with leaders from the three sides—police, city, and community. He first proposed to launch a problem-definition process, suggesting to the parties that without a common definition of the problem, they would have difficulties finding a common solution. However, the police leadership strongly resisted this approach. They argued that focusing on problems would only result in finger pointing—at them! Moreover, the police and city attorneys were unwilling to engage in an effort to define a problem—racial profiling—that they simply did not agree existed.

In response to these concerns, the mediator suggested that the parties instead undertake a broad-based visioning process focused on improving police-community relations. The city and police department accepted this proposal because it seemed a constructive way for representatives from all parties to work collaboratively. The leaders of the Black United Front found this approach appealing largely because it was to be conducted within a framework that promised some form of judicial oversight during the process and after its conclusion.

Thus, only weeks before the city was engulfed in riots in April 2001 following the police shooting of a young African-American man, an ambitious collaborative process called the Cincinnati Police-Community Relations Collaborative—was launched. Jay appointed representatives from the Cincinnati Black United Front, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Cincinnati city and police administration, and the Cincinnati Fraternal Order of Police as his Advisory Group. As its first act, the group decided to invite participation from all citizens in the goal-setting/visioning process. Based on previous studies of tensions in police-community relations, they organized the population into eight stakeholding groups (African-American citizens, city employees, police and their families, white citizens, business/foundation/education leaders, religious and social-service leaders, youth, and other minorities). With considerable cooperation from the media, the Advisory Group invited everyone who lived or worked in Cincinnati or were from surrounding suburbs to answer a questionnaire and participate in feedback groups to envision a new future for police-community relations. Thirty-five hundred people responded, and some 700 of those respondents engaged in follow-up dialogue and agenda-setting.

A Broad-Based Process

The Cincinnati Collaborative used methodologies for engaging conflict (the ARIA Process) and for involving stakeholders in forming goals and action plans to shape the future (Action Evaluation). Citizens and oth ers were invited to answer a simple What, Why, How questionnaire, either online or in writing:

- What are your goals for future police-community relations in Cincinnati?

- Why are those goals important to you and what experiences, values, beliefs, and feelings influence your goals? and

- How do you think your goals can best be achieved?

VISION OF THE FUTURE: A COLLABORATIVE PLATFORM

- Police officers and community members will become proactive partners in community problem solving.

- Build relationships of respect, cooperation, and trust within and between police and communities.

- Improve education, oversight, monitoring, hiring practices, and accountability of the Cincinnati Police Department.

- Ensure fair, equitable, and courteous treatment for all.

- Create methods to establish the public’s understanding of police policies and procedures and recognition of exceptional service in an effort to foster support for the police.

After only a month of a “getting out the voice” campaign, the Collaborative sponsored the first of eight four hour feedback sessions, this one held by religious and social-service leaders at a local church. Following this first session, at a pace of one or two a month for the next six months, members of each stakeholder group were invited to meet with other members of their own group to dialogue about and reach consensus on a platform of principles. Participants in each feedback session selected representatives to work with representatives from the other groups to craft a platform of goals for improving police-community relations (see “Vision of the Future: A Collaborative Platform”). This intergroup platform then guided negotiators, who were the lawyers for the parties who had served all year on the mediator’s Advisory Group, as they worked to successfully craft a settlement agreement.

Judge Dlott ratified the agreement, which will be implemented over five years at a cost of $5 million. In addition to court oversight, the lasting power of the process is that it engaged people’s hearts and hopes.

People’s responses to the questionnaire—especially their “why” stories—captured their concerns about fairness and respecting differences, needs for safety, and expressions of support for the police. The discussions that they participated in were tremendously powerful. They enabled the citizens of Cincinnati to experience resonance with one another—to find commonalities between their own and others’ fears, hurts, hopes, and dreams (see “Participants’Voices”).

Many found this outlet to express themselves critical—up until that point, they felt that they were not being listened to and that their concerns were not being heard. As a young African-American woman said, “When we felt pain, no one from the city came to listen to us. We needed someone to comfort and listen to us.” Healing began as city leaders finally heard people’s ideas. The inclusive and participatory process has helped citizens feel a sense of ownership for the agreement and move from fear and mistrust to cooperation and joint problem solving. The ability and willingness to truly listen and hear others will continue to be critical as Cincinnati’s citizens and public officials begin to implement the changes that are outlined in the settlement agreement.

A Systems-Informed Solution

PARTICIPANTS’ VOICES

- “I would really like to see people respect each other’s values and beliefs, even when they are different. I want all cultures to be treated with respect and fairness . . . In order for us and our children to feel safe, everyone must be treated fairly, it is the only way.”

- “For once in my life I’d like to feel safe . . . I fear for safety, especially for young people.”

- “Police are afraid of doing their job . . . we need to understand their side too.”

In Cincinnati, citizens, public officials, and the police force came to realize that the city needed to move away from enforcement-style policing and toward problem-oriented policing. These two styles represent two ends of a continuum. Enforcement-style policing focuses on the apprehension and prosecution of criminals. Public safety experts have begun to question the enforcement paradigm in recent years for a variety of reasons, not least of which is the struggle to deal with increasing tensions between police and minority communities. These minority groups often feel unfairly targeted by police enforcement activities.

Whether real or perceived, such allegations serve to highlight a problem with the enforcement paradigm, especially in modern American cities with poor, minority neighborhoods. Poverty is considered a leading indicator of crime; that is, the higher the poverty rate in a given area, the higher the crime rate will tend to be. Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine and West End neighborhoods are examples of areas with extreme poverty and also high crime rates. Unfortunately enforcement-style policing does not foster good relationships between police and community members in these kinds of communities, because residents often feel that the police aren’t concerned with what they perceive to be the most important issues, such as vandalism, weapons, and other quality-of-life issues. While most community members and police officers agree that violent criminals must be apprehended and prosecuted, they agree less on other policing priorities.

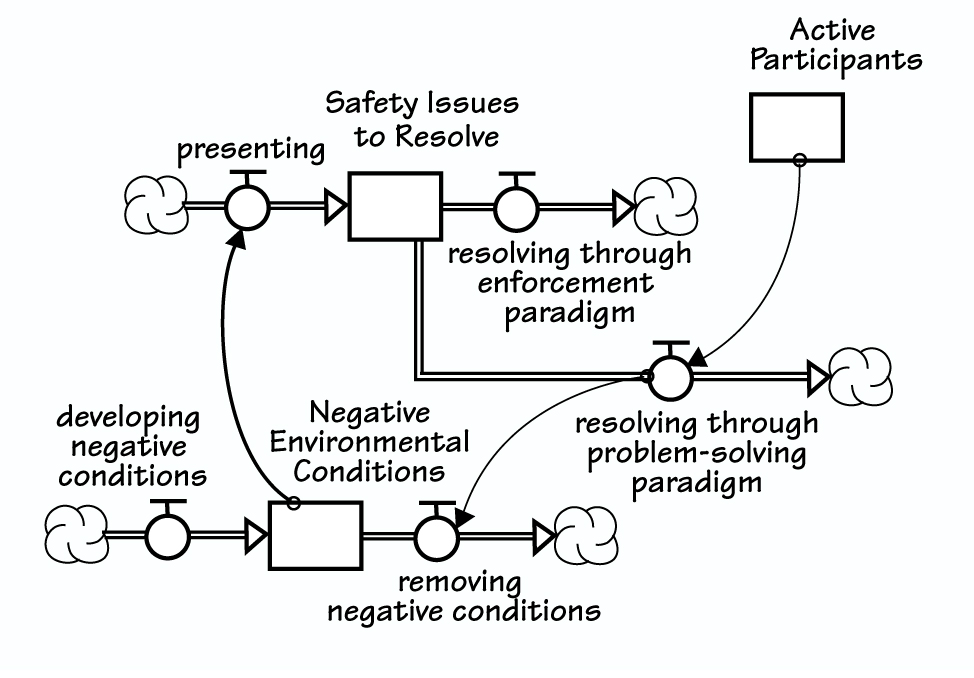

TWO POLICING STRATEGIES

The enforcement approach (the first outflow) seeks to reduce the stock of safety issues by enforcing the laws. Through the Cincinnati Collaborative, stakeholders emphasized more of a problem-solving approach to prevent crimes from occurring (and entering the stock of safety concerns) in the first place by mitigating underlying conditions.

In problem-oriented policing, officers seek to build a working relationship with the community to address quality-of-life issues. Problem oriented policing requires citizen input and involvement. By centering on solving problems with the entire community instead of on simply apprehending and punishing criminals, this model transforms police community relations and prevents crime from happening in the first place. It should not be surprising that a recommendation for problem oriented policing would result from a participatory process such as the one used in Cincinnati.

For community problems to be effectively identified, analyzed, and addressed, citizens and police officers must be able to trust, understand, and communicate with each other in a productive manner. The collaborative agreement signed on April 5, 2002, two days short of the anniversary of the riots, provides for specific mechanisms for police officers to collect the input and concerns of community members and to incorporate this data into their patrolling and policing activities. Through its emphasis on problem solving, the agreement encourages the police to foster working relationships with the residents they serve. In the spirit of mutual accountability, the agreement also spells out through its “community partnering plan” that citizens must be willing to work with police officers to address problems and create solutions. In this way, the police and citizens have formed a mutually beneficial, proactive partnership with the goal of creating safety, respect, and trust.

A Systems Thinking Analysis

Why has the collaborative process described above worked so well? Although we didn’t use system dynamics models in the Cincinnati case, we have done so retrospectively to shed light on how and why the approach was successful, what the implications are for the solution, and where implementation problems might occur. The purpose of these models is not to discover “the Truth” about what happened, or to accurately predict what will happen; rather, we’re trying to build the most useful theory—open to testing!—of why the process has gone the way it has, and to use that theory to think about possible futures.

We’ll start with the solution of implementing a problem-oriented policing strategy (see “Two Policing Strategies”). We can think of safety issues in a community as a “stock.” The stock of safety concerns continually grows as crimes occur and diminishes as they are resolved, usually through the arrest and prosecution of perpetrators. (For an introduction to the language of stocks and flows, go to www.pegasuscom/stockflow.html.) The enforcement approach (the first outflow in the diagram) seeks to reduce the stock of safety issues by enforcing the laws. Through the Cincinnati Collaborative, stakeholders agreed to address safety issues differently. They emphasized adopting more of a problem-solving approach. Such an approach attempts to prevent crimes from occurring (and entering the stock of safety concerns) in the first place by mitigating underlying conditions and focusing more generally on quality-of-life issues within neighborhoods.

The key to making this process work is the active participation of community members in partnering with police to identify and reduce these underlying conditions. Unless residents work closely with the police and city staff, the problem-solving approach will be impossible to implement. So, let’s turn our attention to how community members become active participants. As you’ll see, the model suggests that the visioning process employed in Cincinnati was instrumental in beginning to develop such contributors.

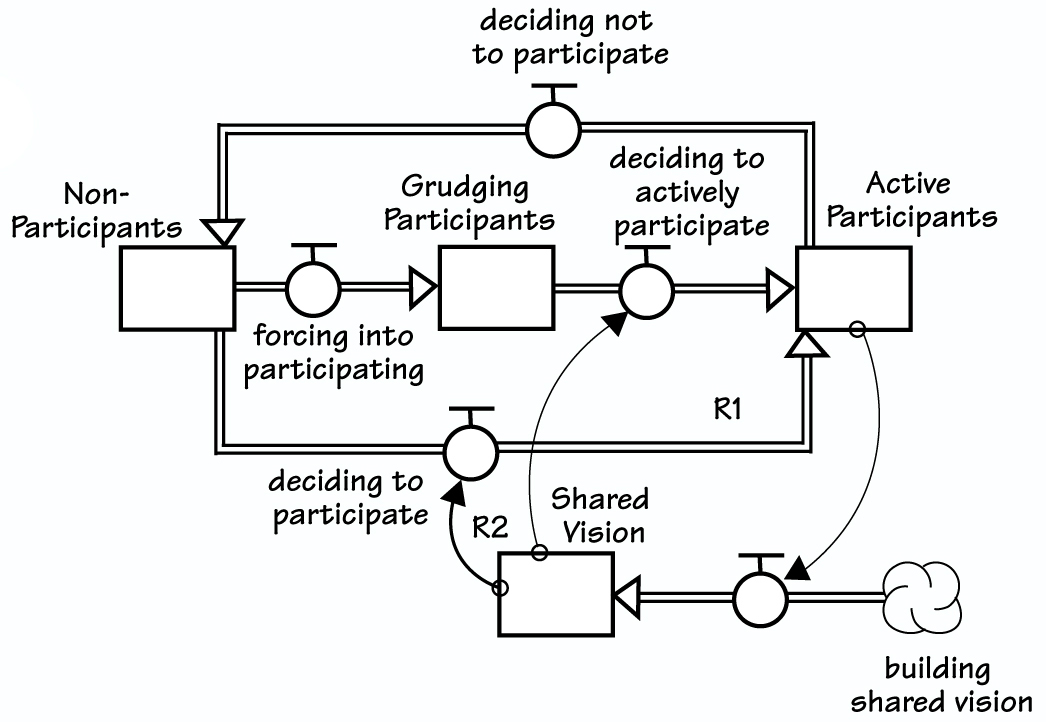

During the intervention, some members of each stakeholder group were what we might call “Grudging Participants” (see “From Grudging toActive Participation”). In the initial meetings, Jay noticed the difference in commitment between individuals who were accepting of and those who were enthusiastic about participating. He wondered how to motivate everyone to take equal ownership for the process. In this case, an unfortunate turn of events actually spurred the participants to new levels of engagement the riots in early April 2001. They dramatically surfaced the problems in the city for all to witness and focused energy and attention on trying to address underlying causes. Optimally, however, groups seeking to emulate this collaborative process can launch their projects in a more proactive way before a crisis requires it!

By getting 3,500 people to discuss their dreams for the city—how it should work and feel—stake holders began building trust and creating a shared vision. Somewhat uncharacteristically, the media seemed to capture this positive outlook as well. This virtuous cycle led to higher levels of participation and commitment to a vision. The end result: There are now more and more active participants involved in the problem-solving approach to combating crime (see R1 and R2 in “From Grudging to Active Participation”). That’s the good news!

Looking Ahead

But, of course, there’s more. The initiative is only beginning. The community must identify and avoid potential barriers to success. To do so, the Cincinnati Collaborative must:

- Build greater levels of trust (keeping participation high)

- Avoid reverting to an enforcement approach (preventing a loss of trust)

- Give them selves time and resources to show success with the problem solving approach (building more trust and shared vision)

Although a participatory process should automatically build trust, several factors threatened to prevent this from happening in Cincinnati. One of the African-American stakeholder groups, the Black United Front, was instrumental in filing the proposed suit against the city. A large part of their strategy was to keep pressure on the civic institutions through negative press and an ongoing economic boycott, even while the collaborative process was forging ahead. So while on the one hand the Black United Front was participating in the collaborative process, they were also continuing their more adversarial activities.

Also, it’s unclear whether the city’s involvement in the Collaborative was a strategic decision—to address social problems through an inclusive process—or merely tactical so it could avoid litigation. As the Black United Front continued to take confrontational actions, the city’s participation became increasingly lukewarm and inconsistent. In this negative cycle, each side was able to cite ample evidence to support its own assumptions about the other side’s antagonistic goals and motivations. The danger in this pattern of behavior is that, over the long run, it might undermine trust. If so, active participants might cease contributing. Let us hope that the momentum of the agreement itself will indeed prove the saying that “Failure is an orphan while success has a thousand parents.” If so, all sides will appropriately share credit for the agreement and work to ensure its fulfillment. Another issue is that, if the level of safety doesn’t increase to satisfy the community’s or police’s expectations, the police will tend to fall back on the more traditional enforcement approach—with the support of some residents. African-American citizens might experience such enforcement activities as racial profiling—something that would seriously reduce trust and perhaps convince many residents to stop participating in the collaborative process. This scenario could undermine or reverse any progress made!

FROM GRUDGING TO ACTIVE PARTICIPATION

The process of building shared vision together—along with the crisis spurred by the April 2001 riots—helped move grudging participants into the stock of active participants. The reinforcing loops (R1 and R2) create a virtuous cycle of increasing numbers of Active Participants.

Thus, in order to keep the current virtuous cycle going, the city must practice the problem solving approach intensively enough to show some improvements in important indicators of safety and quality of life. And leaders should widely publicize those successes. Doing so will keep stakeholders involved (because they’ll see the fruits of their efforts) and also bring others into the process.

What Systems Thinking Adds

Systems thinking isn’t just useful in doing an “after the process” analysis (as described above), but also as part of the development of an intervention. In any conflict that involves multiple stakeholder groups, because participants have different backgrounds and perspectives, they often have difficulty understanding each other. Building systems thinking maps (similar to those in this article) requires stakeholders to use a common language to refine a collective “mental model” of the important system behaviors they wish to address. To be successful, a systems thinking approach also must involve voices from all parts of the systems, giving participants the chance to hear other points of view.

This common language encourages stakeholders to answer the crucial questions: How does this system work and how is it producing the behavior that we see? We used this framework to develop the maps above to determine what convinces stakeholders to participate in the Collaborative and what might cause them to stop participating. Also, because the process of building and refining a collective map breaks down the “us versus them” barriers, participants generally come to trust each other more.

Further, if they desire, a group can convert their maps into computer models to run in public sessions or even over the Internet. Using these simulation models, interested parties can see if the agreed-to goals are achievable, and if so, what strategies would be necessary for achieving them. In this way, the models help participants reach agreement on appropriate goals and strategies and understand how the system will behave over time as the strategies are being implemented.

For example, we mentioned that in the Cincinnati case, the police might begin to feel pressure to revert to an enforcement approach—and that much of the pressure might come from the community! A model can simulate how this pressure might arise and show that if the police and community can ignore it and stick to the new policing strategy, then the pressure will subside as the new approach begins to show success. When people see this “worse before better” dynamic play out in a computer simulation, they are generally better able to wait it out in real life.

Suggestions for Similar Processes

For other organizations and communities experiencing conflict around a contentious issue, the Cincinnati experience holds tremendous promise. Here are some suggestions for how to implement (and improve on) the process employed there:

- Identify stakeholder groups.

- Work with both individual stakeholder groups and cross-stakeholder groups to identify What, Why, and How goals (consider employing or adapting the Action Evaluation Process described at www.aepro.org).

- Use the systems thinking language of stocks and flows or causal loop diagrams to focus discussion and identify high-leverage goals.

- Build simulation models to explore policies for achieving the goals (optional).

- Assemble a cross-stakeholder group to refine the goals during an iterative process of exploring diagrams or models, reflecting, and engaging in dialogue.

- Communicate the resulting goals to others in the stakeholder groups. Use public forums, workshops, and perhaps even the Internet to engage others in the process and make the goals a reality.

The conflict engagement process used in Cincinnati is already a dramatic improvement over the adversarial and legal approach traditionally taken in such situations. Many positive things have resulted, including the development of five goals that all stakeholders agree are worth trying to accomplish. The most important outcome is the commitment by citizens, public officials, and the police department to a community-based problem-solving approach.

By developing the goals together through a participatory framework, the stakeholders have created the foundation for a shared vision of what the community should be and how citizens and city officials should work together. From a systems perspective, this shared vision may be the most crucial component in ensuring the long-term success of the agreement. Only time will tell how the agreement will affect Cincinnati’s well being and if it will be the beginning of the deep healing process the city needs after many years of racial unrest. Systems thinking—as used in this article and as part of similar stakeholder processes—can help us understand how new behaviors will ultimately unfold and create positive and self-fulfilling prophesies.

NEXT STEPS

- Adopt a proactive, preventive, and problem-solving orientation. Look for opportunities to turn crisis into vision, and conflict into change.

- Seek out the people, the process, and the purpose (vision) that can help translate good theory into better practice.

- Look for patterns of behavior over time in complex problems and social change efforts. Weave this understanding into intervention plans right from the start to keep the process moving ahead despite unavoidable obstacles and setbacks.

- Use mapping and modeling as a way to bring people together and give them a common language for dialogue. The resulting maps and models can help people get on the “same page.”