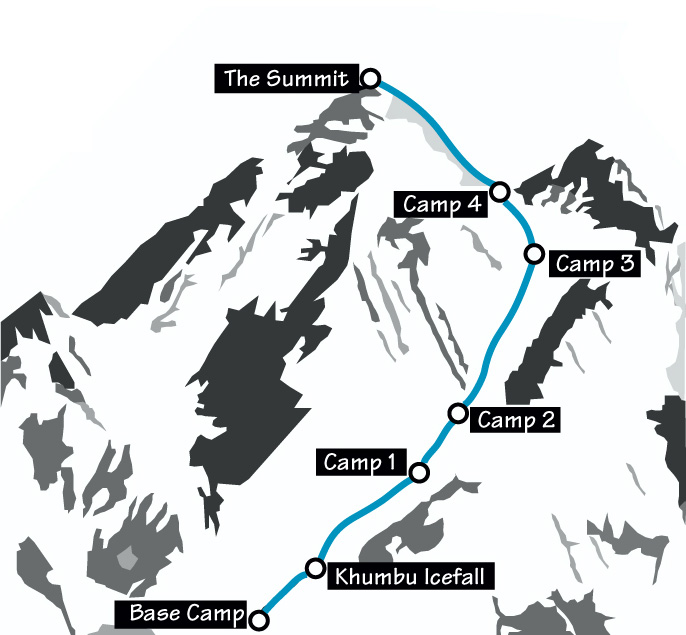

On May 10, 1996, 26 climbers from several expeditions reached the summit of Mt. Everest, the world’s highest mountain. At 29,028 feet, the peak juts up into the jet stream, higher than some commercial airlines fly. A combination of crowded conditions, a perilous environment, and incomplete communications had already put some climbers in peril that day; a late-afternoon blizzard that sent temperatures plummeting sealed their fate.

Descending climbers were scattered along the upper reaches of the mountain when a powerful storm hit. Some people became incapacitated near the summit; others managed to get to within a few hundred yards of their tents at Camp Four (26,100 feet) before becoming lost in the whiteout conditions. Eight climbers would die over the next day and a half. Others would suffer severe frostbite and disability from their Everest summit attempts.

The 1996 Everest climbing season was the deadliest ever in the mountain’s history. The key events of the May 1996 tragedies have been analyzed thoroughly, both from a sensationalist perspective for the general public, and from a more analytical perspective by the climbing community. Now that some time for reflection has passed, we can view the The 1996 Everest climbing season was the deadliest ever in the mountain’s history. The key events of the May 1996 tragedies have been analyzed thoroughly, both from a sensationalist perspective for the general public, and from a more analytical perspective by the climbing community. Now that some time for reflection has passed, we can view the events as a rich metaphor for how organizations cope and survive, or not, under extreme conditions.

Although most of us don’t face life or death situations in the office, we do operate in a volatile environment that demands strong leadership and quick decision-making based on the best information we can gather in a short time. In this sense, we might say that our work teams scale our own Everests every day.

Because any significant undertaking requires leadership of a productive team effort, we begin by sketching out some of the factors essential to “collaborative leadership.” We then examine the case of the 1996 IMAX expedition led by David Breashears as an example of effective collaborative leadership in action. We conclude by drawing lessons from Everest for business leaders.

Collaborative Leadership

Many managers recognize the need for collaborative leadership to help them achieve their objectives in a changing business environment. They have heard that leading in new ways can enable groups to perform at higher levels. The problem is that very few managers really know what collaborative leadership entails or how to implement it. Many think they are leading collaboratively when they are really either just trying to keep everyone happy or continuing to rule with an iron fist couched in friendlier language.

Collaborative leadership is a set of skills for leading people as they work together to accomplish both individual and collective goals (see “Skillful Collaborative Leadership”). First and foremost, collaborative leaders must be excellent communicators of a passionate vision. They must maintain a keen awareness of the many variables that affect their organizations, such as the availability of resources, time constraints, and shifting markets. These leaders must balance the agendas of a group of talented but very different people and work with the team as a whole to help members achieve their highest level of capability. In short, they must be able to weave many complex factors together into a plan to accomplish an overarching goal.

SKILLFUL COLLABORATIVE LEADERSHIP

A collaborative leader creates a safe, clear, and cohesive environment for the group’s work. He or she:

- Functions as a kind of central switching station, monitoring the flow of ideas and work and keeping both going as smoothly as possible

- Ensures that every group member has ownership of the project

- Develops among team members the sense of being part of a unique cadre

- Works as a catalyst, mediating between the outside world and the inner world of the group

- Provides avenues for highly effective communication among team members

A collaborative leader has a mastery of boundary-spanning skills, including capitalizing on the group’s diversity. He or she:

- Develops new projects in a highly collaborative manner, taking good ideas from anyone involved in the process

- Is a dealer in hope rather than guarantees

- Reduces the stress levels of the members of the group through humor and creating group cohesion

- Focuses on encouraging and enabling the group to find and draw on inner resources to meet the goal

- Uses mediation to eliminate the divisive win-lose element from arguments balanced with open but clear decision-making

A collaborative leader inspires the group through vision and character. He or she:

- Realizes that you can only accomplish extraordinary achievements by involving excellent people who can do things that you cannot

- Is absolutely trustworthy and worthy of respect

- Transforms a dream into a compelling vision for the group’s work

- Conveys a sense of humility and integrity

- Has the courage to speak of personal fears

- Models the ability to cut through unconscious collusion and raise awareness of potential red flags

- Maintains grace in a crisis

Collaborative leaders do not rely on pure consensus when making decisions. Their role on the team is to stay aware of the big picture and to keep in mind all the factors that are necessary to make the goal happen. Thus, although they collect input and information from others, they must ultimately make a decision that they feel best serves the organization’s needs. This decision may go against the expressed desire of one or more team members. To keep dissenters engaged, collaborative leaders must articulate a vision so compelling that team members are willing to make their personal aspirations secondary to achieving the overall objective.

In a crisis, teams tend to fall apart as their members approach basic survival level. On Everest, survival means having enough air to breathe to keep blood circulating to the brain and staying warm enough to avoid frostbite and hypothermia. Similarly, managers of a business in a critical state must understand the organization’s core functions and find ways to sustain those activities until they can muster additional resources.

In crisis situations, people’s “fight or flight” instincts will cloud their judgment unless the leader has instilled in them a strong sense of the vision; has modeled the ability to work through the dilemma and keep moving toward the goal; can foresee possible scenarios for resolving the crisis; and can communicate the different actions needed to reach safety. A collaborative leader must master the skill of creating a complex web of relationships among team members that binds the group together and that resists the pressures that seek to separate them under stress. For when collaborative leadership is missing, personal survival and individual goals negate group goals, planning falls apart, and communication is shattered.

Collaborative Leadership on Everest

During the challenging May 1996 climbing season, the IMAX expedition led by David Breashears succeeded where others failed, in that the group achieved its goals of creating footage for the IMAX Everest movie, conducting scientific research, and putting team members on the summit safely. A measure of this success is attributable to Breashears’s collaborative leadership style.

Breashears and his group were united in their personal goals to summit Everest, and in the group goal of bringing the Everest experience back to the masses through large-format cinematography. Unlike some of the other teams on the mountain, Breashears’s IMAX expedition was fully funded by the film’s producers and by the U. S. National Science Foundation. Because of this financial backing, Breashears had the luxury of handpicking his crew, and he showed an outstanding ability to judge both physical and psychological readiness.

At base camp, Breashears’s approach to team-building centered on creating opportunities for the team to get acquainted, bond socially, and develop a sense of mutual respect and interdependence. For example, at dinner, team members contributed delicacies from their home cultures. This rich social context and intimacy was sustained beyond base camp. As the IMAX team moved up the mountain, the process of filming the movie helped to unite the team further.

On May 8, just before several other expeditions headed out for the summit, Breashears made the difficult call to postpone his team’s attempt and descend to a lower camp. His chief priority was the team’s safety. Although Breashears gathered the input of his team members, no one questioned that the final decision to make or abandon the summit attempt would be his alone.

When the other teams ran into trouble on summit day, Breashears stopped filming. His group devoted all their energies to rescuing the survivors, bringing them down the mountain, and assisting in providing medical treatment. These actions saved the lives of two climbers. Breashears and his team chose to risk their chance to summit and their film project in order to respond to the immediate needs of people who were in jeopardy. The group’s heroism further cemented their bonds. Breashears’s display of character under duress, for example, his refusal to film the injured climbers for profit, additionally bolstered the team’s spirit.

After the tragedies and rescues of the remaining members of the other teams, Breashears’s group returned to base camp to consider their options. In the end, after the memorial services and a short time to reflect, they decided to return to the mountain to make a summit attempt. Once they reached high camp, Breashears made the hard decision to cut one team member from the summit team. The climber had cracked two ribs through coughing on the way up to high camp, and Breashears judged that she would not be strong enough to safely make the summit. Again, this decision was his to make, and the team was strong enough that they accommodated the loss of one member with little loss of morale.

In preparing for the summit attempt, Breashears ran through a number of scenarios for the climb. He mused: “In my mind, I ran through all the possibilities of our summit day. When I got to the end of one scenario, I would work through another. I know that the effects of hypoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain) and sleep deprivation and the tug of Everest would cloud my decision making. I wanted to have rationalized a decision for the most likely scenarios of the day down here in the relative warmth of my sleeping bag and the security of my tent” (High Exposure, Simon & Schuster, 1999).

Despite the stress of the preceding events, the IMAX team successfully summitted Everest and captured the glory of the highest point on earth on film. Part of the success of the expedition came from the incredibly talented team. But Breashears’s ability to masterfully create both environmental and psychological support for his climbers and articulate an unwavering vision and sense of integrity bring him close to the collaborative leadership ideal.

Unconscious Collusion

Collaborative leadership alone cannot create success. When crisis strikes, team members must rely on their own inner resources — courage, conviction, and, a more elusive resource, character — to get them through the challenges at hand. Although the leader can model and instill a vision of uniting personal and team objectives, the successful resolution of crisis ultimately rests on the strength of earlier team-building efforts.

In Into Thin Air (Anchor Books, 1997), the best-selling book about the May 1996 Everest climbing season, Jon Krakauer noted that in one of the other expeditions “each client (a climber who has paid to be part of a professionally guided expedition) was in it for himself.” Such thinking precludes effective collaboration. In addition, he states that many of the clients adopted a “tourist” attitude. They expected the staff to prepare the mountain for them, so that they would only need to put one foot in front of the other to succeed.

At the same time, according to Krakauer, on the morning of the summit attempt, several clients on his team expressed concerns about the summit plan they were following, but none of them discussed their doubts with their leaders. If there had been closer collaboration within the teams, such concerns may have been discussed more openly. In reflecting on these actions and attitudes, we must consider the role of unconscious collusion. In groups, unconscious collusion occurs when no one feels either empowered or responsible for calling out red flags that could spell trouble.

In the rapidly changing conditions and troubled communications that Krakauer documents in his book, unconscious collusion played a central role in the tragic outcomes.

This kind of unconscious collusion can lead to poor decisions and potential disasters in companies as well. The ongoing pressures on businesses for results and nonstop success — comparable to “summit fever” (the desire to get the summit despite escalating risks) among a group of climbers — create overwhelming pressure for employees to go along with the crowd, to bury their doubts, and to ignore risks. In successful groups, someone always raises questions when they sense problems with a certain course of action. But unfortunately, unless the team has developed high levels of trust, personal ownership, responsibility, and open communication, no one will feel it is their duty or right to question a prior decision. To counter unconscious collusion, the collaborative leader must constantly nurture team intelligence, model and reinforce the need for open communication, encourage dissenting viewpoints, and maintain an open-door policy.

What Does This Mean for Business Collaboration?

Looking at the case of the 1996 Everest expeditions through the lens of collaborative leadership can naturally lead to the following conclusions about business collaboration under crisis:

Consistency in collaborative leadership is vitally important. One of the lessons we can glean from the success of the Breashears team is the critical role of consistent leadership, particularly in a crisis. The confusion that results when leaders vacillate between different leadership styles can undermine a group’s sense of teamwork and the ability of different members to step into leadership roles. In this context of blurred boundaries and roles, a sudden leadership vacuum can lead to paralysis and “every man for himself behavior.

In contrast, over time, predictable, consistent collaborative leadership inspires commitment, confidence, and loyalty from a team. In this atmosphere, people know what to expect from their leaders, and what their leaders expect from them. If the leader must withdraw for any reason, the team’s strength and strong vision seamlessly carry it though the temporary vacuum at the top.

The ongoing pressures on businesses for results and nonstop success — comparable to “summit fever” (the desire to get to the summit despite escalating risks) among a group of climbers — create overwhelming pressure for employees to go along with the crowd, bury their doubts, and ignore risks.

The ideal collaborative leader shares much in common with a good movie director. David Breashears’s training as a movie director likely supported his ability to motivate others and lead collaboratively. The director is the leader on a movie production, but all the members of the team are mutually dependent. On a movie production, each person’s role is clear, and each task must be executed in sequence.

The movie director’s challenge, similar that of a team leader, is to:

- find and organize the best talent,

- prepare the environment for the production,

- draw on and incorporate the team’s ideas,

- create a clear goal,

- articulate a story and vision for the production, and

- weave together the complex web of aspirations and talents in the group to create a coherent and compelling end product.

The movie production process also offers a strong element of real-time learning, in that it incorporates processes for discovering errors and correcting potential failures before the project reaches a critical stage. The director reviews “dailies” for each day of production. In collaboration with cast and crew, he or she decides which scenes work and which need to be reshot, keeping in mind time and budget constraints. This regular review process serves as an excellent way to prevent teams from falling into unconscious collusion and ignoring warning signs.

The “director” in a business setting — the leader — must ensure that team roles are clear; that members clearly understand the project’s objectives and milestones; and that the group as a whole frequently and openly assesses the progress to date against the original plan. He or she must do so in a nonthreatening setting and demonstrate flexibility in adapting the plan to changing conditions. Many businesses have adopted formal after-action review processes that occur both in the course of a project and after its completion.

Collaborative leaders develop flexibility in the team for dealing with rapidly changing conditions. Successful groups must recognize the need for flexibility in approaching rapidly changing conditions. For instance, in order to sustain collaboration in crisis and mitigate survival anxiety, Breashears and his team collectively reviewed potential scenarios, developed contingency plans, and stayed in touch with each other on summit day. When survival anxiety becomes too high in business, because of ill-defined or shifting management priorities, downsizings, competition, or loss of market value, managers must prepare for a strong wave of fight-or-flight reactions among team members and for a fall-off in collaborative efforts. The development of alternate strategic scenarios is an emerging business practice that can support the flexibility of project teams and help them respond quickly to changing conditions.

Collaborative leaders are supported by interdependent team members who take ownership for achieving common goals. As Krakauer and others have noted, many of the clients on the commercial expeditions in 1996 felt they had been led to expect that they were entitled to reach the peak of Everest; that their every need would be catered to; and that the dangers were minimal if they followed the formula laid out by the expedition leaders. This overreliance on the leaders put a tremendous burden on those individuals and led to a vicious cycle: As the clients became more and more dependent, the leaders’ ability to prepare “the mountain for the clients” decreased.

In the business arena, no organization can afford to cultivate dependence in its employees — and thereby put unnecessary stress on managers. Successful groups combine strong interdependence among members with individual responsibility and ownership for the outcomes of the project. This combination is vitally important in the harsh environment of the new economy.

When Preparedness Isn’t Enough

Leaders will be most successful in turbulent environments if they inspire team members to go beyond their limitations; coach them to make the teams’ goals their own; practice a consistent, predictable collaborative leadership style; and present an unwavering vision. In the new business climate, managers would do well to cultivate the skills that make for a great director, rather than those that make for a great supervisor. More and more, leaders must form teams made up of contractors, partners, suppliers, and subsidiary employees — none of whom directly report to one another. They will need to organize more frequent project reviews, so that team members are continually checking their assumptions, learning in real time, and correcting mistakes before they become serious. In this way, collaborative teams can avert potential disaster.

When expedition leaders initially prepare to climb Everest, they focus tremendous energy on preparedness: physical training, supplies, equipment, portage, logistics, and staffing. Teams that undertake these operations with skill and foresight greatly enhance their chances of success on the mountain. However, the 1996 season on Everest revealed that excellent preparation isn’t enough. When a team’s very survival is threatened, the quality of their interactions, relationships, and decisions become key to a successful outcome.

In business, the process of facing a new challenge is similar: Organizations devote much effort to preparedness, logistics, and resources, but they often fail to invest in promoting leadership and collaboration skills. What we learn from Everest is that it is exactly this investment in human capability that can mean the difference between success and failure. With a strong grounding in collaborative skills and effective collaborative leadership, teams can learn to pull together in times of crisis rather than fall apart.

Dori Digenti is president of Learning Mastery (www.learnmaster.com), an education and consulting firm devoted to building collaborative and learning capability in client organizations. She is facilitator of the Collaborative Learning Network, a group of leading companies working together to understand and enhance collaboration skills.

NEXT STEPS

Institute a failure analysis process — such as the U. S. Army’s after-action review — for all projects. Ensure that your analysis includes the role that leadership played in the project: Was it too authoritarian or laissez-faire?

Look at how your organization Look at how your organization deals with crises. Is there a pattern in the responses? How could your leaders improve their ability to support teams through times of stress?

Examine how your organization is building collaborative skills in the next generation of leaders and how it is enhancing those skills in the current generation.

References

Bennis, Warren and Patricia Ward Biederman, Organizing Genius: The Secrets of Creative Collaboration (Perseus Books, 1997)

Breashears, David. High Exposure (Simon & Schuster, 1999)

Krakauer, Jon. Into Thin Air (Anchor Books, 1997)

A Farewell—System Dynamicist Donella Meadows

Among her other accomplishments, Dana was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize; cofounded the Balaton Group; developed the PBS series “Race to Save the Planet”; was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship; and served as a director for several foundations. In 1999 she moved to Cobb Hill in Hartland Four Corners, Vermont. There she worked with others to found an eco-village, maintain an organic farm, and establish headquarters for the Sustainability Institute.

Dana’s mother, Phoebe Quist, has referred to her daughter as an “earth missionary.” Meadows described herself as “an opinionated columnist, perpetual fund-raiser, fanatic gardener, opera-lover, baker, farmer, teacher and global gadfly.” Dana was a true pioneer and visionary who was committed to — and succeeded in — making the world a better place. For copies of her “The Global Citizen” columns and information about the Sustainability Institute, go to www.sustainer.org. For more details about Dana’s life and work, go to www.pegasuscom.com.

A memorial service will be announced at a later date. Memorial donations may be made to The Sustainability Institute or to Cobb Hill Cohousing, both at P. O. Box 174, Hartland Four Corners, VT 05049.