One of the most compelling insights of systems thinking is that our perceptions can create our reality. How empowering and humbling to realize that what we take as a “given” may be the result of processes that we ourselves have set into motion. So it is with the “syndrome” cited above, in which a manager in advertently initiates a dynamic that leads to eroding employee performance. In a time when worker turnover is so costly, the thought that employers might actually be creating personnel problems instead of solving them is sobering.

Winners Versus Losers

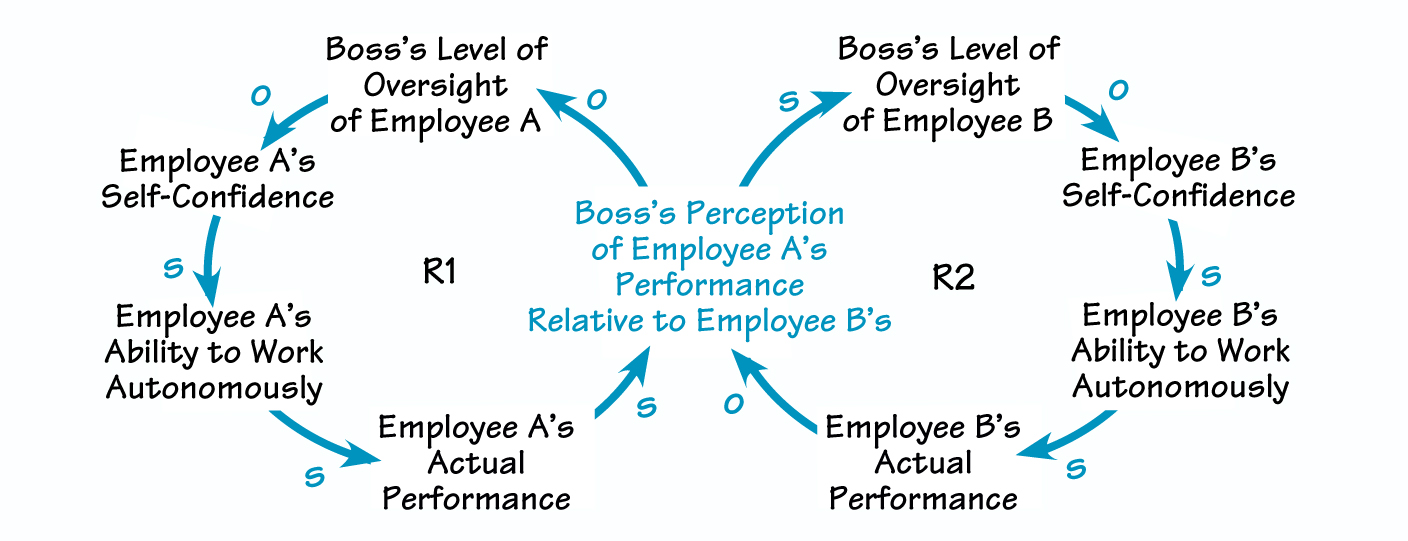

How can a manager unintentionally undermine an employee’s success? According to Manzoni and Barsoux, the process generally begins with a simple trigger a missed deadline or certain personal style that confirms a boss’s preconception of a particular subordinate as an under performer (seeR1 in “Set-up for Failure”). This perception causes the manager to focus more attention on that employee’s work. Although these actions are meant to help the worker improve his performance, they actually undermine his sense of mastery over his job. Stripped of his self-confidence, the employee loses his ability to make autonomous decisions. This passivity confirms the boss’s assessment of the employee’s abilities, leading her to be even more vigilant.

SET-UP FOR FAILURE

In this variation of the “Success to the Successful” structure, by closely monitoring Employee A’s work, his manager undermines his sense of self-confidence, which eventually erodes his actual performance. Employee A’s failure confirms his boss’s perception of him as a weak performer. At the same time, Employee B, judged to be a strong performer, thrives.

At the same time, another employee thrives under the tutelage of the same manager (R2). Success on one project leads to more challenging assignments. Despite possessing the same skills as the low performer, this individual far out shines his colleague, ending up on the fast track for promotion. This dynamic is a variation of the classic “Success to the Successful” archetypal structure.

How do managers come to consider some workers as “winners” and others as “losers”? These categorizations often have less to do with performance than with personal biases. Once we’ve judged someone in a certain way, we’re more likely to focus on details that confirm that assessment and less likely to take into account new information. With one preconceived notion, we subtly shift certain people to the “B” team.

Compounding the problem is that, according to Manzoni and Barsoux, “research shows that bosses tend to attribute the good things that happen to weaker performers to external factors rather than to their efforts and ability (while the opposite is true for perceived high performers: successes tend to be seen as theirs, and failures tend to be attributed to external uncontrollable factors).” So, in the face of this unfortunate human tendency, how can we maintain a sense of objectivity in dealing with the people we manage?

Eternal Vigilance

First, it’s generally easier to prevent are in forcing process from starting than to stop it once it’s been set in motion. To do so, Manzoni and Barsoux recommend that managers clearly communicate expectations with all new hires. They also suggest that bosses and workers maintain ongoing discussions about performance and relationship issues. Finally, the authors exhort managers to continually challenge their assumptions about individual employees. By avoiding simplistic categorizations and comparisons, we can help to assure that all workers have equal opportunity to contribute to an organization’s success.