What are the potential gains and pitfalls of launching an organizational learning initiative in a company whose governance model has historically been “top-down”? The story of Philips Display Components captures the drama inherent in this sort of journey. Philips Display Components (PDC) makes the color cathode ray tubes that are used in television sets. Located in the U. S., the company is owned by Philips, which is headquartered in the Netherlands. In the 1980s, PDC had about 2,500 employees and $250 million in sales. It also had several daunting problems. Smarting from undercapitalization from its former owner and a stiffening of foreign competition, it decided to launch a series of change efforts in 1986 that eventually led it to explore the principles and tools of organizational learning.

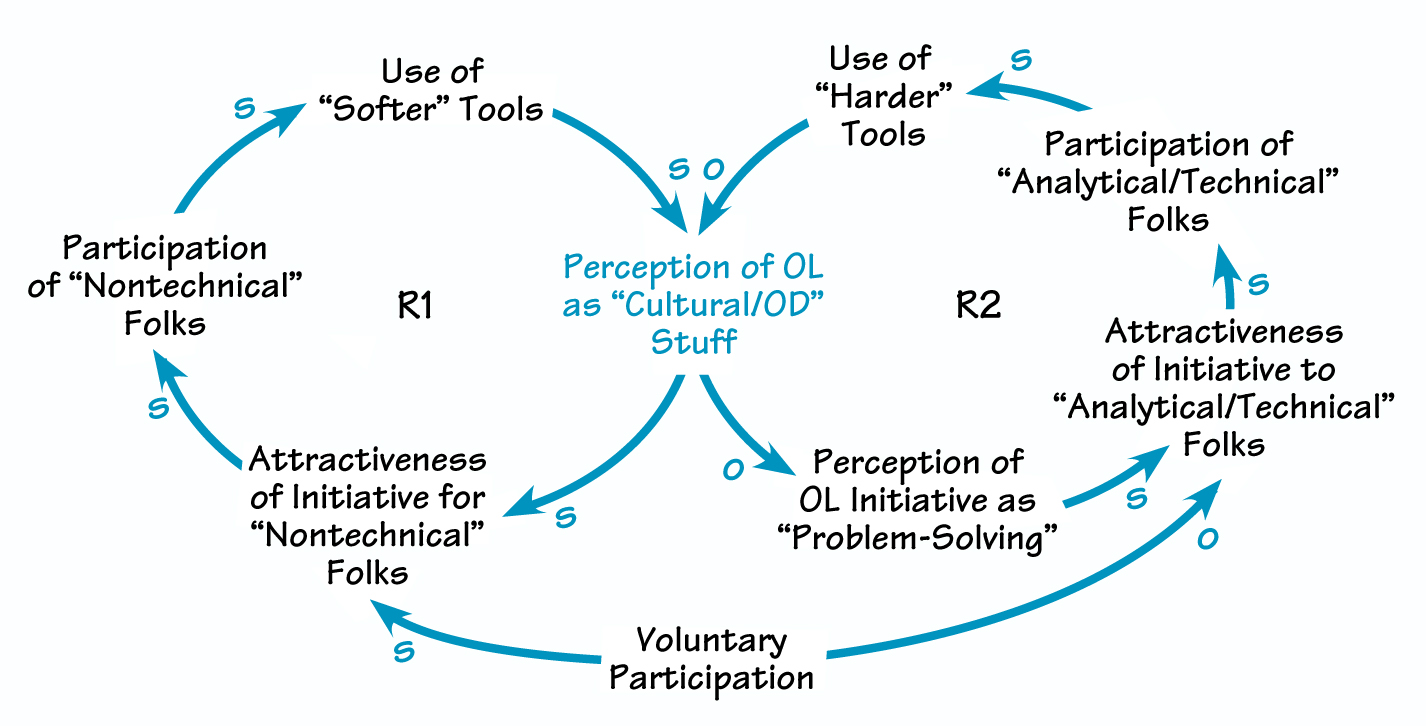

Because of a widespread perception of the organizational learning effort as mere “OD stuff,” the initiative tended to attract mostly people who had an affinity for the “softer” tools of OL, which reinforced the original perception (R1). As this perception grew, people began to see the initiative as less effective for “real” problem-solving. The more technical employees ignored the initiative, and use of “harder” tools declined—further reinforcing the perception of the initiative as too “soft” (R2).

Initiating the Change Effort

In March 1992, the company invited nine PDC managers to attend the MIT Organizational Learning Center’s core course, which covers the various tools of organizational learning. The goal was to then introduce the initiative gradually to a diagonally cross-functional group of people, who could take the change process further and engage the rest of the organization. To that end, the management team decided to make participation in the core course voluntary.

As people began attending the OLC course, the PDC management team encouraged them to use organizational learning tools in all aspects of their work, such as in the strategic planning process, product development, and so forth. These tools included dialogue, which helps participants surface and share mental models; balancing advocacy and inquiry, which fosters generative conversation; the left-hand/right-hand column, which enhances people’s ability to navigate difficult conversations; and the ladder of inference, which helps people understand how their assumptions about the world shape their behavior. In addition, participants began to explore systems thinking tools, including behavior over time graphs, which reveal changes in key variables; causal loop diagrams, which show the systemic structures that generate behavior patterns; and simulation modeling, which shows how business decisions play out over time.

The people who were most familiar with these tools then became champions of them, introducing others to the tools and encouraging use of the tools throughout the organization.

A Closer Look at the PDC Experience

The learning initiative at PDC scored some successes, particularly in improving relations between management and the union. However, in many ways, it fell victim to some inherent systemic structures at work in the company.

Assumptions About Change. One of these problematic systemic structures involved the assumptions that people at PDC made about the change effort. As in numerous large companies, the PDC learning initiative was seen by many as mere “cultural, OD stuff.” In addition, because participation was voluntary, the effort attracted people who already had an affinity for organizational improvement and the idea of vision. Seeing the purpose of the learning initiative as an opportunity to work toward a shared vision rather than to solve a specific problem, these participants tended to be more drawn to tools such as dialogue and team learning rather than systems thinking, modeling, and some of the other more technical tools. Over time, the situation began to resemble a version of the “Success to the Successful” systems archetype, in which one set of tools began to gain more support than the other set (see “Success to the ‘Softer’ Tools”). Eventually, some of the more technical managers dismissed the learning effort as too “soft” and declined to support it.

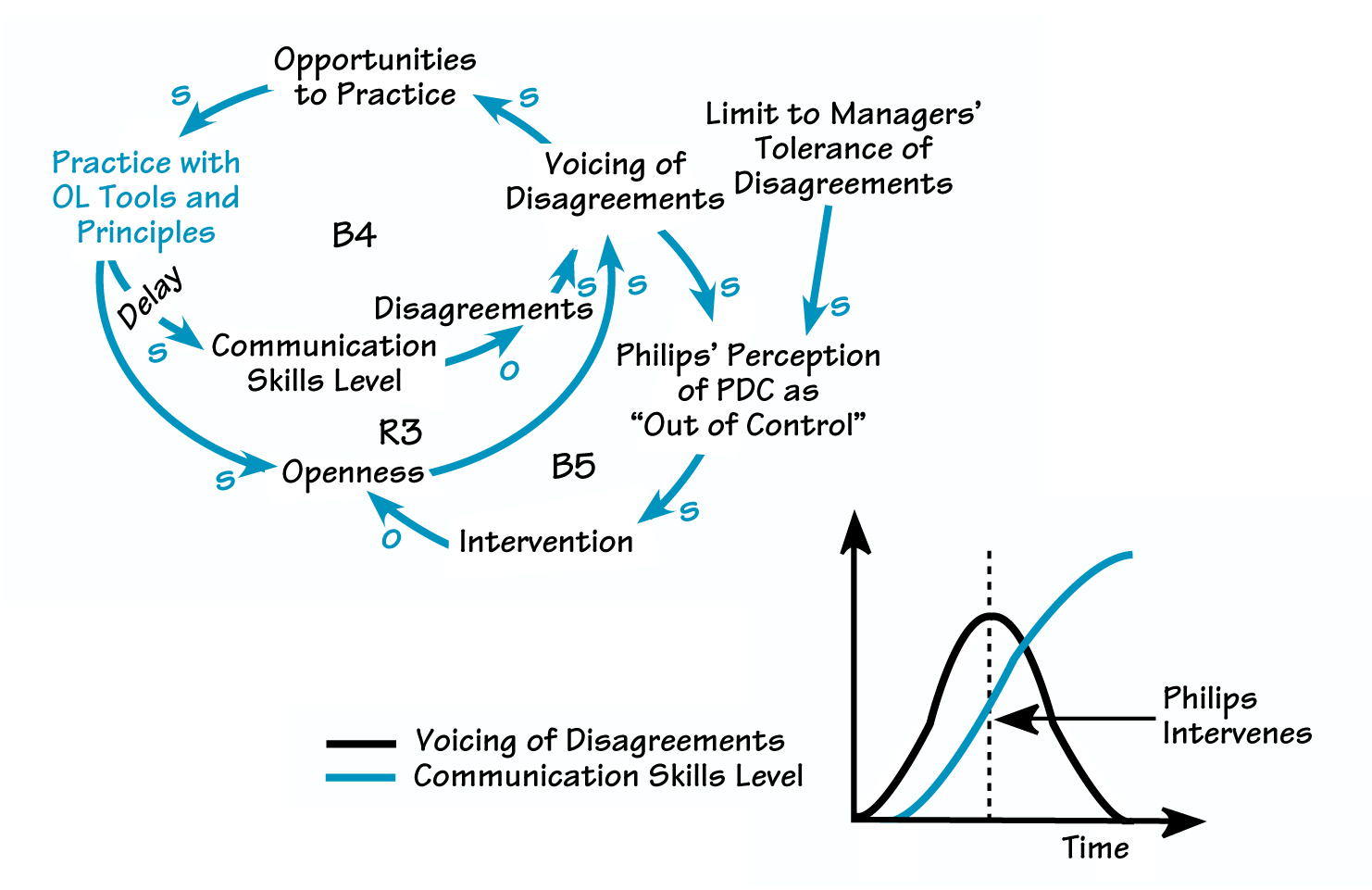

“Worse Before Better.” Another problematic structure for PDC involves the well-known tendency of things to get “worse before better” as an organization begins implementing change. During such times, a change initiative becomes very vulnerable. At PDC, as people began using OL tools in the early stages of the learning initiative, a sense of openness began to build within the company (see “Worse Before Better”). People felt increasingly secure in sharing their opinions about and criticisms of the new initiative. Eventually, as they also mastered new communication skills through the application of OL tools, these disagreements would have tapered off because the participants would have begun addressing the real roots of conflict through their use of the new skills (B4 and the behavior over time graph).

Unfortunately for PDC, Philips took action before the “worse” could turn into the “better.” During the delay in which communication skills were ramping up (B4), the freely delivered feedback alarmed Philips’ top management, who decided that PDC was “out of control” (B5). Top Philips management thus began intervening in PDC’s learning initiative, choking off the fragile culture of openness that PDC had begun to build, and effectively reducing the voicing of disagreements. Ironically, the voicing of disagreements that Philips found so disturbing would have petered out on its own eventually.

The learning effort—both its successes and its failures— yielded important insights about the nature of change.

Power and Authority. As in most hierarchical organizations, managers at PDC found it difficult to begin sharing power. The act of assuming power can also be frightening to many people, because it means added responsibility, risk, and accountability. Organizational learning can help overcome this reluctance. Once people have learned something, they are in a stronger position to take on power because their new knowledge has lessened the risks involved. However, this process takes time. If Philips had been better able to tolerate the delays in the organizational learning journey, PDC might have had more success encouraging the sharing of power.

Success or Failure?

Was PDC’s experience with organizational learning a “success” or a “failure”? The question is difficult to answer. Even though PDC couldn’t clearly show a correlation between practice of the learning disciplines and an increase in profitability, the company did see a desirable change in teams who practiced the learning disciplines. Individuals gained a stronger sense of their own contribution to current reality and learned to see the world differently. People also learned to reframe issues, help others to clarify their perspectives, and engage in tense discussion with less blaming than before. Finally, and perhaps most important, the learning effort—both its successes and its failures—yielded important insights about the nature of change that are pertinent and valuable for any organization.

WORSE BEFORE BETTER

The increased voicing of disagreements that resulted from the climate of openness that PDC began creating through its learning initiative alarmed Philips’ top managers, who intervened in the initiative and reversed its progress.

Iva M. Wilson is the retired president of Philips Display Components, where she served in that role from 1986 to 1996. She has also participated in the design team that created the Society for Organizational Learning (SoL) and was appointed SoL’s first president, a post that she held until the end of 1997. She serves as a board member of The Environmental Research Institute of Michigan and of Michigan Future Inc.

A longer version of this article appears in Making It Happen: Stories from Inside the New Workplace (Pegasus Communications, 1999).