What do you think of when you consider corporate politics? Do you think of backstabbing, gossip, and self-interest, or do you think of alliance building, interdependence, and trust? It’s rare that we refer to an organization or person as “political” in a positive manner.

How do you define politics? The quick answer is “power.” Merriam Webster defines it as “competition between competing interest groups or individuals for power and leadership.” People who use political relationships in the workplace often wield power that is either disproportionate to their position or enhances their power beyond the position they hold. But where does this power come from? How is it that some people can exert tremendous influence, while others can’t even lay claim to the power that comes with their title? Is political power always exploitative, or can it be moral and constructive?

At its core, political power comes from the ability to understand what other people fear or desire, and to use that understanding to influence their behavior. The possibility of this power being misused is obvious even without the cautionary tales of corporate fraud and corruption that have plagued the news over past decades. Yet some of the most morally powerful leaders in recent history had a very strong grasp of this power and used it widely.

TEAM TIP

Use the exercise in this article to help recognize when your behavior is values-driven and when you’re tempted to act based on fear or desire.

The Dalai Lama, for example, wields tremendous political influence. As the deposed leader of an occupied country, he has very little positional power, but because of his reputation as a compassionate, humble, and moral spiritual leader, he often speaks on the world stage to influence international political policy. He advises heads of state and is the spiritual leader of millions. The Dalai Lama uses his deep understanding of the struggles of humanity to foster compassion and moral responsibility on a global level. Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. used their understanding of the human condition and our fears and desires to motivate people to make tremendous sacrifices, and advanced the moral and political development of their nations.

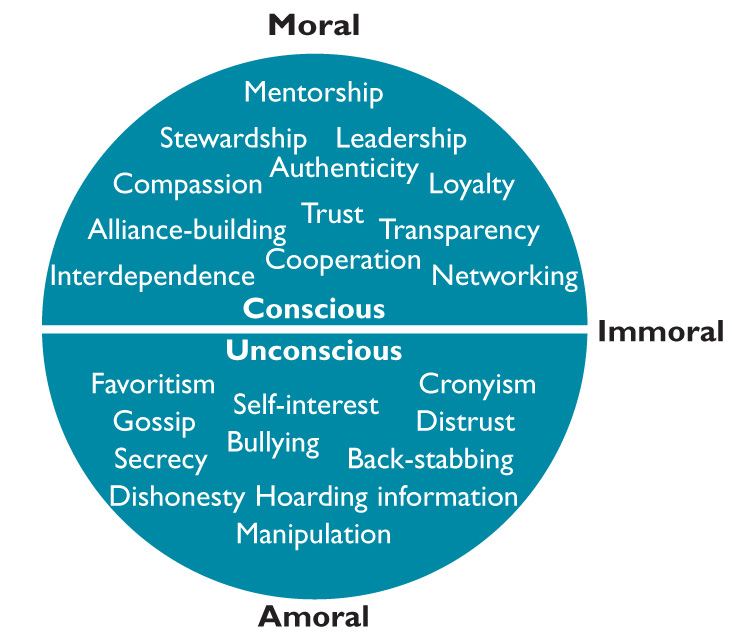

So how do we differentiate between using political power for good or ill? I propose that there are three levels to political power: immoral, amoral, and moral (see “The Political Sphere”). The key factor in deciding which is in use is self-awareness.

- Amoral Political Power Unconsciously understanding and manipulating others with no awareness of your own motivating fears and desires.

- Immoral Political Power Consciously understanding and influencing others without examining and understanding your own motivations.

- Moral Political Power Consciously examining, understanding, and evaluating your own motivation, fears, and desires before using your understanding of others to influence them.

It may be hard to differentiate between the results of amoral and immoral use of political power; in both cases, wielders do not taking moral responsibility for their actions because they do not recognize their own motivation. The difference is that the immoral person consciously and knowingly manipulates others, and therefore carries greater moral responsibility for the results. Consider these examples:

THE POLITICAL SPHERE

A COO tries to amass power by keeping his peers and subordinates in the dark about client expectations and organizational processes. He prohibits managers from collaborating to solve problems, or even from having management status meetings. He does not support employee development or conduct performance reviews, and he criticizes managers in front of each other and their subordinates. Unconsciously unable to accept that success in others is not a personal threat, he tries to maintain an image of superiority while actively tearing down the reputations of other leaders and managers. He is unaware that his fear of being seen as incompetent is inhibiting organizational growth, causing high turnover in management and poor efficiency and morale. While these tactics may make him seem more competent in the short term, in the long run he is costing the company money through attrition and lost efficiency, and limiting the quality of customer service. This pattern of behavior is ultimately self-defeating.

A manager furthers her career by skillfully using the cultural language of her company to promote an appearance of strong leadership skills to her superiors, while actively removing more experienced and productive employees from her team. Recognizing her employees’ ambition for advancement, she uses flattery and favoritism to mine for personal information and gossip, using it as informational currency to bargain for other information or discredit those she perceives as a threat. She negates the experience and skills of her employees while covering up her own deficiencies. She does not recognize that her fear of incompetence is motivating her to either control or remove others who may recognize it. Consciously, her loyalty to leadership is strong, but she often changes alliances with peers and has no sense of obligation to her employees. While she has been able to maintain a close relationship with leadership, the attrition rate, reputation, and productivity of her team has suffered, and her superiors are beginning to ask questions.

A director is hired to manage a team that has had issues with productivity, efficiency, and morale. She takes time to get to know each of her employees personally, learning their strengths, weaknesses, and ambitions. She spends part of a day with each employee letting them “train” her on their jobs, so she can understand their day-to-day challenges. She quickly promotes experienced employees to line manager roles and publicly credits team members’ important successes. She forms cross-departmental alliances that benefit her team and improve the quality of work for the whole department. Her team becomes more efficient, happier and better at solving problems and working cooperatively with clients.

Were you able to recognize which story corresponded with which type of political power? The first person did not understand how fear and insecurity motivated him to sabotage his managers. While this is obviously a destructively shortsighted behavior, his total lack of awareness puts this example in the amoral political power category.

The second manager purposely sought out information and alliances that would allow her to promote her own reputation while actively damaging those of her employees. She clearly understands how cultivating personal relationships can be used to mine for valuable and potentially damaging information on others. However, she has not examined her own motivations, which stem from territorialism, competition, and fear or distrust of employees who might “show her up.” This makes her an immoral user of political power.

The final manager cultivated interdependent relationships with her employees and colleagues, taking extra steps to educate herself about the nature of the work, a necessary step in building credibility and trust. She used this trust to heal relationships between team members, establish clear expectations, and change their status in the organization. Since she is aware of her own ignorance of process as a new manager and fosters trust through transparency, she seems to be using her power in a moral fashion.

Cultivating Moral Power

So how do we cultivate moral political power? How do we influence others without corrupting our own values? The answer lies in self-awareness. Most people strive for self-awareness in some way. We may talk to our friends or a trusted counselor about our problems. We may take time for quiet reflection, prayer, or meditation.

These techniques are excellent ways to take a deeper look at our own motivations and evaluate our actions. Here is an exercise designed to help you recognize and evaluate your motivations and then make ethical choices in the workplace:

Ethical Awareness Exercises

Exercise 1 This exercise gives you a baseline, or mental checklist, against which to evaluate your motivations when making decisions at work.

At work I desire… (choose all that apply) public recognition, advancement, increased compensation respect, independence, collaboration, companionship, friendship, status, influence, control, stability, (add any additional items from your own experience)

At work I fear… (choose all that apply) losing my job, being seen as incompetent, not being liked, not being respected, being the last to know important news, the ambitions of others, the power of others, being deceived, getting caught, making a mistake, lack of control, instability, being shown up, competition (add any additional items from your own experience)

My most important values at work are…

Honesty, Integrity, Creativity, Trust, Success, Kindness, Respect, Loyalty (add any additional items from your own experience)

Choose your top two answers from each question and write them out.

The responses to the first two items describe areas in which you may unconsciously be influencing others, or ways that others might be influencing you. The last response describes your core working values.

Example:

At work I desire respect and stability.

At work I fear losing my job and getting caught making a mistake.

My most important values at work are honesty and respect.

Exercise 2 This exercise helps you recognize when you are not acting in accordance with your core working values. It also helps you identify alternative ways to approach situations that play on your desires or fears.

Think of a situation where any of your core fears and desires may have affected your behavior. Identify the motivating fears and/or desires, and then compare them to your core values. What was the positive and negative outcome of the described situation? (see example below)

Situation: I made a minor mistake on a team report, but convinced myself and my boss that it was the fault of a junior team member.

Fear: making mistakes

Desire: respect

Values in use: dishonesty and disrespect

Comparison: My fear of making mistakes and looking bad caused me to go against my core working values and use my senior status to blame someone else for my mistake.

Outcome: While I didn’t have to admit I’d made a mistake to my boss, I damaged the possibility of having a positive relationship with my junior coworker, and I provided him with an example of unethical behavior in senior employees.

Imagine a way you could have dealt with the situation without violating your core working values. What might have been the outcome?

Example: I could have admitted my mistake openly and given the junior team member public credit for his accurate work.

Outcome: I would have built personal credibility and trust through honesty and integrity. In addition, I would have set a positive example for the junior team member, possibly increasing his loyalty and creating the opportunity to provide mentorship.

These exercises can help you recognize when your behavior is values-driven and when you’re tempted to act based on fear or desire. Keep in mind that everyone acts unconsciously sometimes. Ethical growth is only possible when we can take an honest look at our behavior and learn from our mistakes.

The Price of Power

The power to influence others comes with a price; the responsibility to act ethically. Selfish use of political power is ultimately self-defeating, as it erodes trust, commitment, and loyalty in its victims. Ethical use of political power can motivate people to work together to accomplish goals that benefit everyone. Taking an honest look at your own motivations is a first step toward building and using political power constructively and ethically.

Michelann Quimby is CEO of DiaMind Consulting in Austin, Texas.