The modern workplace is far less than ideal for workers who want integrated lives. As one engineer put it, “The problem isn’t for those who have decided to put work first and family second. They can do just fine here. And it isn’t for those who have decided to put family first. They don’t go far here but that’s okay because that’s what they’ve decided is important. The problem is for people like me who want both — a good family (life) and a good career.”

The struggle to have both a good personal life and a good career arises from a dominant societal image of the ideal worker as “career-primary,” the person who is able and willing to put work first, and for whom work time is infinitely expandable. This view translates into work practices that include dawn meetings; planning sessions that run into the evening, often ending with the suggestion to “continue this over dinner”; and training programs requiring long absences from home. Commitment is measured by what one manager proudly declared as his definition of a star engineer: “someone who doesn’t know enough to go home at night.” At lower levels in the organization, the belief in the dominance of work translates into tight controls over worker time and flexibility.

In situations where “ideal workers” are assumed to be those whose first allegiance is to the job, people with career aspirations go to great lengths to keep personal issues from intruding into work. Some people give false reasons for leaving work early: They feel that attending a community board or civic meeting is not likely to brand them as uncommitted, while taking a child for a physical might. Some secretly take children on business trips. Others leave their computers on while picking up children from sporting events, hoping that colleagues passing by will think they are in a meeting.

When Individuals Try to Change

BUSINESS CASE FOR RELINKING WORK AND FAMILY

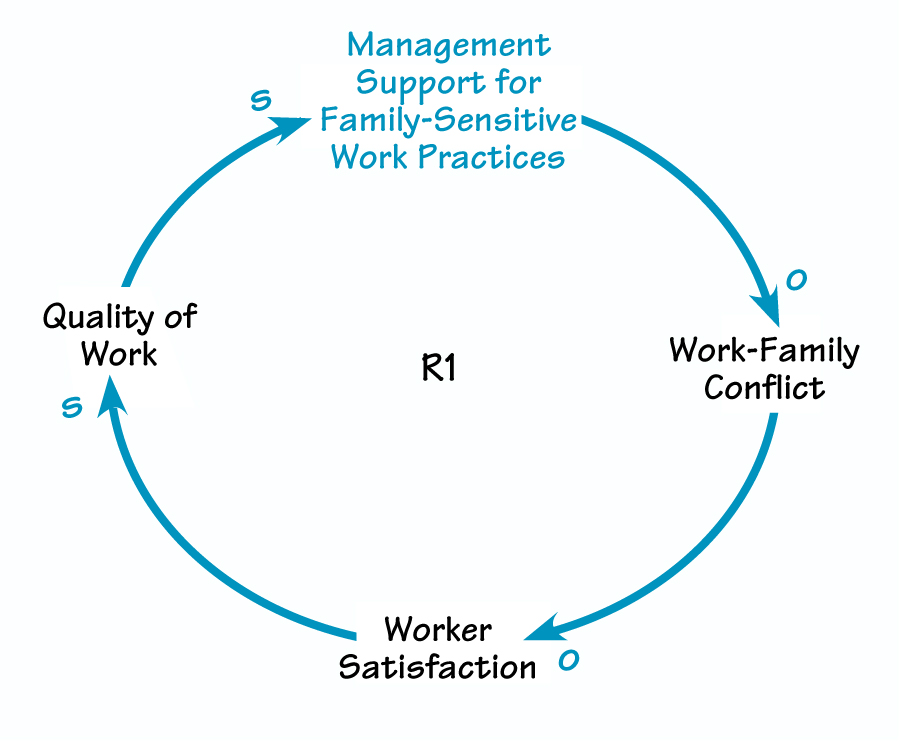

As management’s support of family-sensitive work practices rises, employees experience less work-family conflict, leading to greater worker satisfaction and better quality of work.

Some workers, because of their positions, their financial resources, or their perceived value as employees, are themselves able, at times, to forge satisfactory links between work and family. The rest simmer with discontent. In all cases, energy and loyalty are diverted unnecessarily from the organization (see “Can Your Company Benefit from Relinking?”). Because people feel powerless to deal with these concerns on their own, relevant work-related issues cannot be discussed at the collective level, where real systemic change might yield significant business and personal results.

When individuals change, but the system remains the same, there may be unexpected negative consequences for both. For example, one team leader arranged a four-day schedule to cut down on a long commute and to spend more time with her children. Not only did this arrangement serve her needs, but because the team leader rotated group members to take her place on the fifth day, she developed their self-management skills. By all measures, including productivity and satisfaction, the group was thriving. But the arrangement did not last long. In the end, the manager was stripped of her supervisory duties and moved to the bottom category of performance. Management regarded the team leader’s efforts as a negative reflection of her future potential and management capability. Similarly, a full-time sales technician who negotiated earlier hours was forced to give up the arrangement because her managers were unwilling to adjust their daily demands to conform to the schedule they had approved. From the beginning, the managers imposed so many “exceptions” that the employee was putting in extra hours and was unable to pick up

CAN YOUR COMPANY BENEFIT FROM RELINKING ?

Employee Indicators

- Complaints about overload

- Stress and fatigue

- Sudden changes in performance

- Low morale

Organizational Indicators

- Loss of valued employees

- Reduced creativity

- New initiatives that falter

- Decision-making paralysis

- Inefficient work practices: continuous crisis, excessive long hours, frequent emergency meetings

her child at school much of the time — the reason she wanted the earlier hours in the first place. In the end, she reverted to her old schedule and became very disillusioned.

In this context, it is not surprising that managers typically view requests for flexibility as risky to grant. Even though they may sympathize and want to grant such requests, especially when it comes to their most valued employees, they worry about the potential negative consequences of allowing such arrangements. Not only do they worry that productivity might suffer, but they fear that, in negotiating and monitoring these special arrangements, they might have an increased workload. As a result, managers often end up sending negative signals indicating that the use of flexible, family-friendly benefits is a problem for them and for the company as a whole.

The important point is that it is problematic when work-family issues are viewed as individual concerns to be addressed only through flexible work practices, sensitive managers, and individual accommodations. This approach often fails the individuals involved, and it may lead to negative career repercussions. More important, by viewing these issues as problems, companies miss opportunities for creative change. For example, management could have perceived the unusual arrangement of the team leader with the four-day schedule as a chance to embrace this innovative work practice and to rethink the criteria for effective management. Similarly, the revised schedule of the sales technician could have been an opportunity to rethink the way time is used in the organization.

Consider, also, the following example: two workers, one in sales and one in management, requested a job-sharing arrangement that would have allowed each of them to spend more time with their families. In an extensive proposal, they outlined how they would meet business needs under the new arrangement. As an added benefit, they also suggested a way to revamp the management development process so that a sales representative, working under the guidance of a sales manager, took on limited management duties. Such an apprenticeship model promised to be a significant improvement over the existing practice of “throwing sales people into management” with little training. Nevertheless, the company rejected the proposal because it was seen as stemming from a private concern (a desire for more personal time) rather than a work concern (a wish to increase the organization’s effectiveness), and the opportunity was missed.

Thus, despite the potential benefits to the company, making the link between work and employees’ personal lives in today’s business environment is, to say the least, not easy. Significant organizational barriers — for example, assumptions about what makes a good worker, how productivity is achieved, and how rewards are distributed — militate against such linkage. Work-family benefits are often designed and administered by the human resource function but implemented by line managers. Associating strategic initiatives with line managers and work-family concerns with human resources reinforces perceptions that business issues are separate, conceptually and functionally, from individuals’ personal lives.

Putting Work-Family Issues on the Table

Putting work-family concerns on the table as legitimate issues for discussion in the workplace turns out to be liberating. By talking about such issues, people realize that they are not alone in struggling to meet work and family/ personal demands. Such discussions help people see that the problems are not solely of their own making, but stem from the way work is done today. The process of transforming personal issues to the collective level engages people’s interest and leads to more creative ways of thinking. It also provides a strategic business opportunity that, if exploited correctly, can lead to improved bottom-line results (see “Business Case for Relinking Work and Family” on p. 1).

For example, at one site we documented the work practices of “integrated” individuals — people who link the two spheres of their life in the way they work. We found that integrated individuals draw not only on skills, competencies, and behaviors typical of the public, work sphere, such as rationality, linear thinking, assertiveness, and competition, but also on those associated with the private, personal sphere, such as collaboration, sharing, empathy, and nurturing. Their work practices include working behind the scenes to smooth difficulties between people that might disrupt the project, going out of their way to pass on key information to other groups, taking the time from their individual work to teach someone a new way of doing something, building on rather than attacking others’ ideas in meetings, and routinely affirming and acknowledging the contributions of others. We showed the value-added nature of this work—the way it prevented problems, enhanced organizational learning, and encouraged collaboration. Offering a new vision of the ideal worker as an integrated individual, someone who brings skills to the job from both spheres of life, helps the organization recognize the importance of hiring and retaining such individuals.

Where appropriate, we also pointed out to management the dissonance between policy and practice. For example, at an administrative site, despite the presence of a wide range of work-family policies, managers limited their use to very minor changes in daily work times. Employees dealt with the situation by “jiggling the system” on an ad hoc, individual basis to achieve the flexibility they needed, often by using sick days or vacation time. Thus, for instance, a man whose mother was chronically ill had to take a combination of sick days and vacation days to be with her. The costs to the site for this companywide behavior were considerable in terms of unplanned absences, lack of coverage, turnover, and backlash against people who took the time they needed. It also created employee mistrust of an organization that claimed it had benefits but made using them so difficult that the result was lower morale and widespread cynicism.

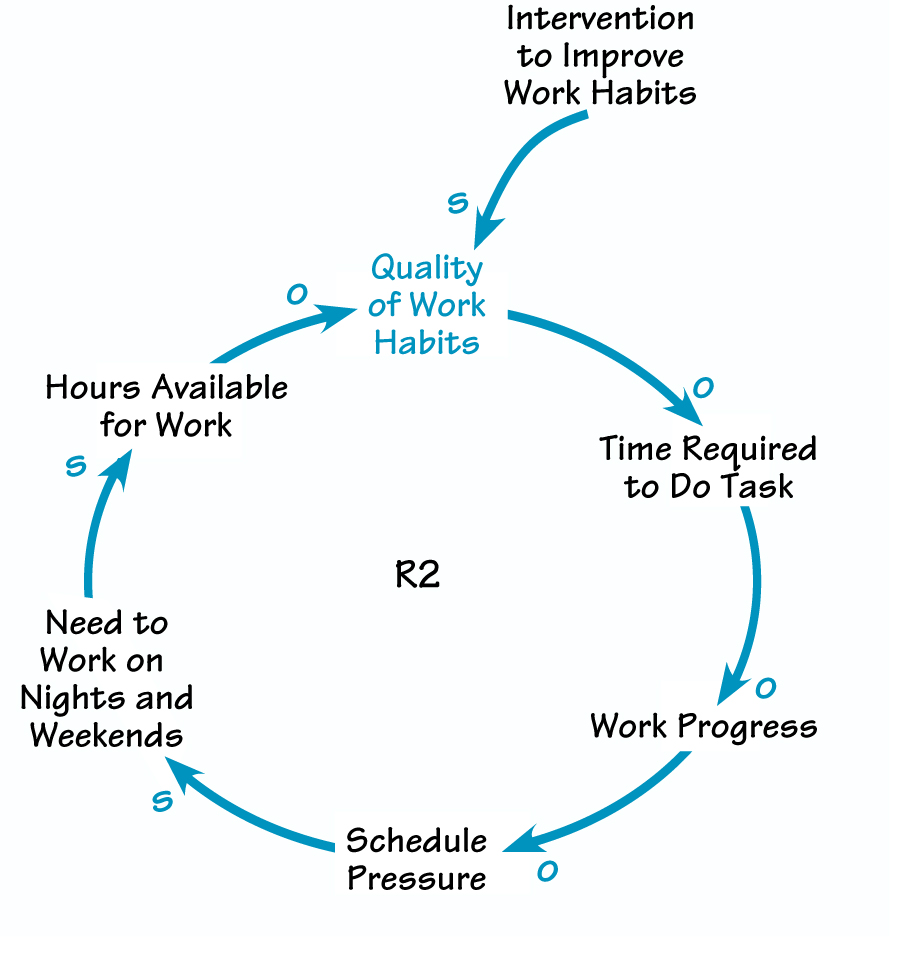

By bringing family to bear on work, we also focused attention on the process by which work is accomplished (see “How Long Hours Become the Norm”). In one sales environment, for example, we found that a sales team habitually worked around the clock to complete proposals for prospective customers. In the morning, the workers were rewarded with cheers from managers and coworkers, complimenting them on their commitment and willingness to get the job done. In response to our interventions, one manager recognized that this behavior reflected poor work habits and made it tough on these people’s family lives. Not only were their families suffering, but it took several days for these workers to recover, during which time they were less productive.

The manager told his team that their behavior demonstrated an inability to plan. He also began to share his perceptions with other managers. As a result, the sales team began to recognize and reward new work habits such as planning ahead and anticipating problems rather than waiting until they were crises.

We have found that changes in work practices can be brought about by looking at work through a work-family lens, linking what is learned from that process to a salient business need, and pushing for change at each step of the process (see “The Synergy of Linking Work and Family”). We begin to make the systemic link between work practice and work-family integration by engaging three lines of questioning:

- How does work get done around here?

- What are the employees’ personal stories of work-family integration?

- What is it about the way work gets done around here that makes it difficult (or easy) to integrate work and personal life so that neither one suffers? Ultimately, however, success also depends on the existence of two specific conditions:

- a safe environment that minimizes individual risk, freeing employees to take part in the change; and

- room in the process for engaging people’s resistance — in other words, addressing their objections, concerns, and underlying feelings with a view toward creating options that were not previously envisioned.<;i>

HOW LONG HOURS BECOME THE NORM

Creating Safety and Engaging Resistance

By giving people permission to talk about their feelings and their personal dilemmas in the context of redesigning work, a surprising level of energy, creativity, and innovative thinking gets released. But raising these issues may not be easy for those who fear they will be branded as less committed or undependable if they acknowledge such difficulties. At the same time, managers who are used to viewing gains for the family as productivity losses for the business may fear they will bear all the risks of innovation.

Therefore, collaboration and sharing the risks across the organization are important aspects of the process. In concrete terms, this means getting some sign from senior managers that they are willing to suspend, if only temporarily, some of the standard operating procedures that the work groups have identified as barriers both to work-family integration and to productivity. Such a signal from upper management also helps people believe that cultural change is possible and provides higher-level support to individual managers seeking to bring about change. The point is that employees need concrete evidence that they are truly able to control some of the conditions that affect their own productivity. And managers need assurance that they will not be penalized for experimenting in this fashion.

The process of relinking work to family creates resistance because it touches core beliefs about society, success, gender roles, and the place of work and family in our lives. We found, however, that such resistance almost always points to something important that needs to be acknowledged and addressed collaboratively.

Engaging with this type of resistance means listening to and learning from people’s objections, incorporating their concerns and new ideas, and working together to establish a dual agenda. To be effective, the process cannot be shortchanged. It requires trust, openness, and a willingness to learn from others.

THE SYNERGY OF LINKING WORK AND FAMILY

This example comes from an engineering product development team. Because managers at this site were good at granting flexibility for occasional emergency needs, most of the employees did not discuss or overtly recognize work-family issues as a problem. However, the long hours they felt compelled to work made their lives difficult. Here we found that addressing these personal issues helped uncover cultural assumptions and work structures that also interfered with an expressed business goal: shortening time to market.

At this site, we found that the team operated in a continual crisis mode that created enormous stress in the workplace and interfered with the group’s efforts to improve quality and efficiency. This was an obvious problem for integrating work and personal life. One person, for example, said that she loved her job but that the demands ultimately made her feel like a “bad person” because they prevented her from “giving back to the community” as much as she desired.

By looking at the work environment in terms of work-family issues, we found that the source of the problem was a work culture that rewarded long hours on the job and measured employees’ commitment by their continuous willingness to give work their highest priority. It also prized individual, “high-visibility” problem solving over less visible, everyday problem prevention.

Our interventions challenged these work culture norms. We also questioned the way time was allocated. Jointly, we structured work days to include blocks of uninterrupted “quiet time” during which employees could focus their attention on meeting their own objectives. This helped employees differentiate between unnecessary interruptions and interactions that are essential for learning and coordination. And the managers stopped watching continuously over their engineers, permitting more time for planning and problem prevention rather than crisis management. The result, despite contrary expectations, was an on-time launch of the new product and a number of excellence awards.

The changed managerial behavior persisted beyond the experiment. And the engineers learned to reflect on the way they used time, which enabled them to organize their work better

Challenges

The next challenge is how to sustain these efforts over the long term and to diffuse them beyond the local sites. Lasting organizational change requires mutual learning by individuals, by the group, and by the system as a whole. It is important to continue to keep the double agenda on the table, ensuring that benefits from the change process continue to accrue to employees and their families as well as to the organization. If not, the individual energy unleashed will dissipate — triggering anger and mistrust within the organization.

What’s more, if local changes are to be sustained and if lessons from them are to be diffused, the work needs to be legitimized so that operational successes become widely known. Given the tendency to marginalize and individualize work-family issues, the overt support of senior management is essential here. Such support reinforces “work-family” as a business issue that is owned by the corporation as a whole.

Lasting change also requires an infrastructure, a process for carrying the lessons learned and the methodology used to other parts of the organization. In one organization, that process took the form of an operations steering committee working hand-in-hand with the research team to carry on the work in other parts of the corporation.

Our experience also suggests that multiple points of diffusion must exist. We sought opportunities, for instance, to present our work as part of special events as well as operational reviews and to look for internal allies among line managers, people involved in organizational change, and so on. Diffusion is also a challenge because, as people reflect on how the various operational pilots meet business needs, they tend to want to pass on to other teams only the results that yielded the productivity gains, rather than information about the process itself. This tendency shortchanges the process and seriously undermines the chances for replicating its success and sustainability.

Conclusion

As corporations continue to restructure and reinvent themselves, linking such change efforts to employees’ personal concerns greatly enhances their chances for success. Such relinking energizes employees to participate fully in the process because there are personal benefits to be gained. It also uncovers hidden or ignored assumptions about work practices and organizational cultures that can undermine the changes envisioned.

But relinking work and family is not something that can be accomplished simply by wishing it were so or by pointing out the negative consequences of separation. It is something that touches the very core of our beliefs about society, success, and gender. And it implies rethinking the place of families and communities and a new look at how we can nurture and strengthen these vital building blocks of our society.

The assumed separation of the domestic and nondomestic spheres breeds inequality, since present practices, structures, and policies — at all levels of society — favor the economic sphere above all others. As a result, employment concerns are assumed to take precedence over other concerns; achievement in the employment sector is assumed to be the major source of self-esteem and the measure of personal success. And, since employment skills are most highly valued and compensated, they dominate government, educational, and organizational policy

In the end, the goal of relinking work and family life is not simple and it is not just about being “whole.” It is about shifting to a more equitable society in which family and community are valued as much as paid work is valued, and where men and women have equal opportunity to achieve in both spheres. Such change is possible and provides real benefits not only to individuals and their families, but also to business and society.

Suggested Further Reading

Bailyn, L., Breaking the Mold: Women, Men and Time in the New Corporate World. Free Press, 1993.

Hochschild, A., The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home. Avon Books, 1997.

Perlow, L., Finding Time: How Corporations, Individuals, and Families Can Benefit from New Work Practices. Cornell University Press, 1997.

Schor, J., The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. Basic Books, 1993.

This article is excerpted from Relinking Life and Work: Toward a Better Future (Pegasus Communications, 1998), which is an edited version of a report originally published by the Ford Foundation.

Rhona Rapoport is co-director of the Institute of Family and Environmental Research in London, England. Lotte Bailyn is the T Wilson (1953) Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Deborah Kolb is professor of management at the Simmons Graduate School of Management and director of the Simmons Institute on Gender and Organizations. Joyce K. Fletcher is professor of management at the Simmons Graduate School of Management. Contributing authors include Dana E. Friedman, Barbara Miller, Susan Eaton, and Maureen Harvey.