So prevalent are relationship troubles that most of us merely accept them as the way things are. A Time magazine article in 2002 went so far as to say, “Until recently, being driven mad by others and driving others mad was known as life.” The article, titled “I’m OK. You’re OK. We’re not OK,” questioned whether it was wise to include “relational disorders” in the newest edition of a diagnostic manual. What would happen, the columnist asked, to notions of personal responsibility? How could anyone ever be held accountable for anything? After all, you can fire or sue a person, but not a relationship. Besides, he concluded, relationship troubles are simply a fact of life. You’re better off keeping your eye on individuals, where responsibility can be clearly assigned and appropriately taken.

I doubt many people would disagree. There’s already enough blame in organizations without adding another excuse: “It wasn’t me. My relationship made me do it.” But taking a relational perspective doesn’t preempt people from taking responsibility. Paradoxically, just the opposite happens. When people think in relational terms, they are more willing and able to take responsibility for their part in any problems or difficulties.

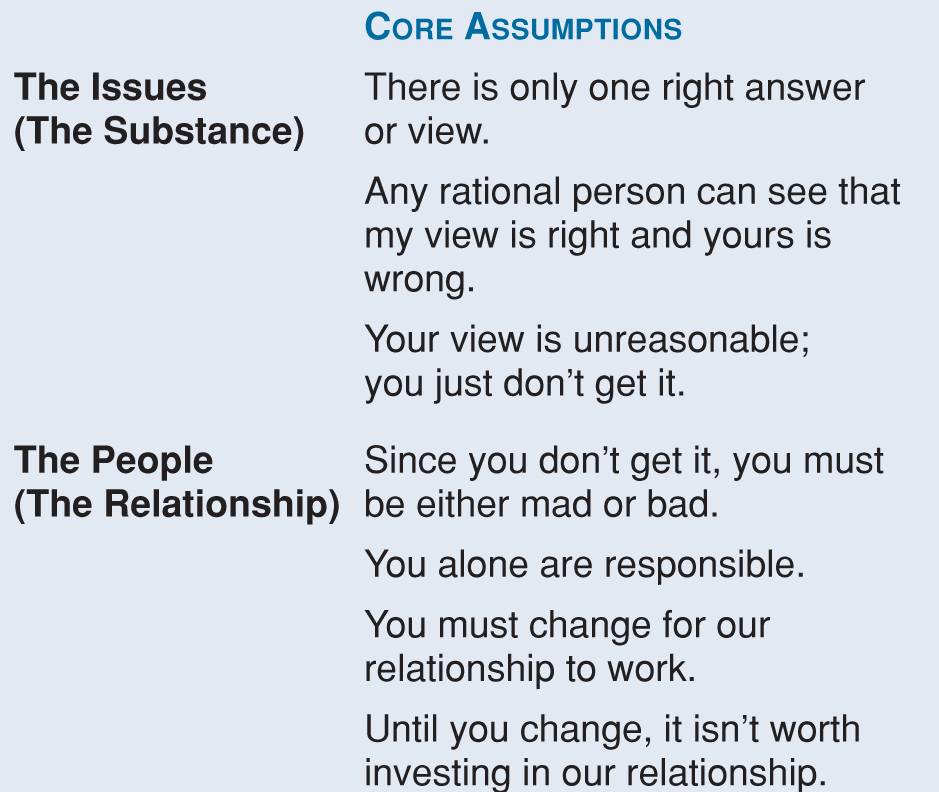

To illustrate, this article introduces two perspectives that leaders might take to any differences, challenges, or troubles they face. The more common is what I call the individual perspective, based on the assumptions that there is one right answer, people either get it or don’t get it, and when they don’t, their dispositions are largely to blame. When leaders hold this perspective, their relationships grow weaker over time, and many break down altogether.

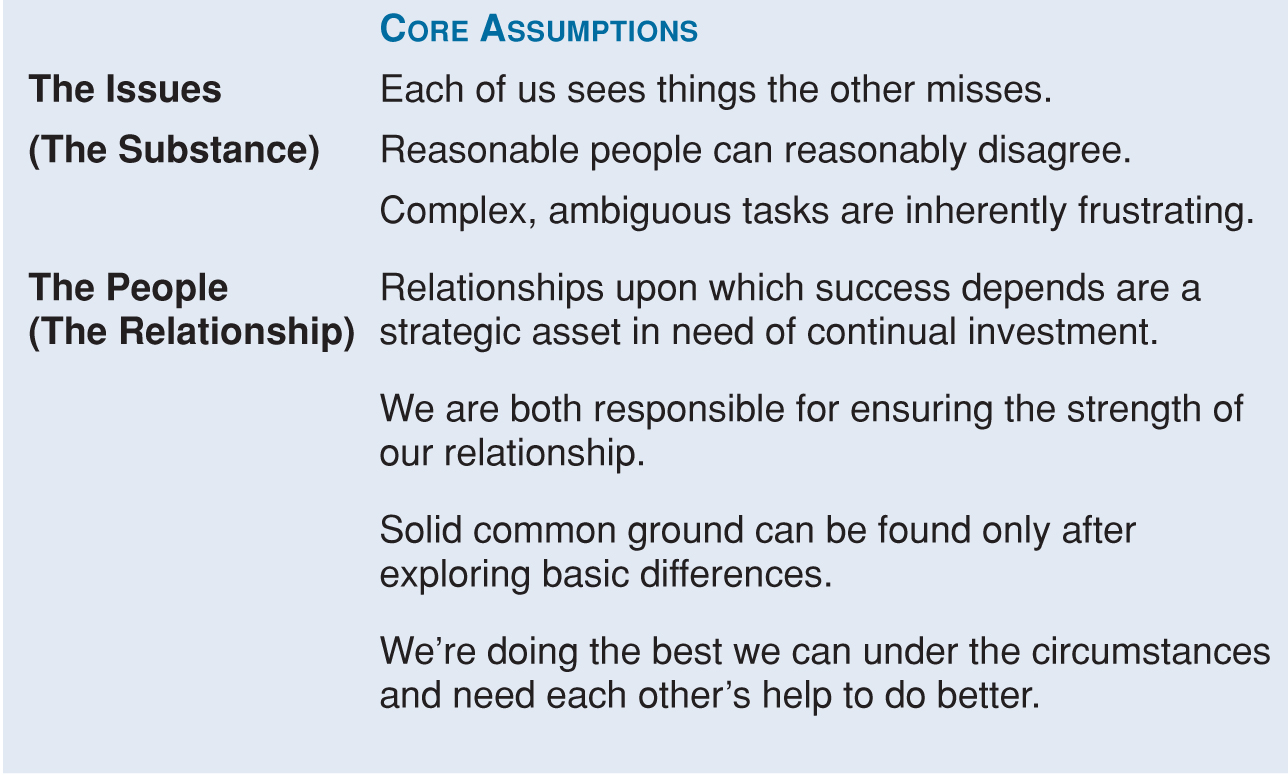

Less common is what I call the relational perspective, based on the assumptions that different people will see different things, that solid common ground can only be found after exploring basic differences, and that the strength of a relationship will determine how well and how quickly people can put their differences to work. Leaders who take this perspective are able to use the heat of the moment to forge stronger relationships. Let’s take a look at each perspective, then consider both in light of recent research on relationships.

The Individual Perspective

THE INDIVIDUAL PERSPECTIVE

This perspective rivets our attention on individuals and turns it away from what everyone is doing to contribute to outcomes no one likes. As a result, when we differ with others, or others behave in ways we find difficult, we assume they are either mad (irrational, stubborn, out of control) or bad (corrupt, selfish). With the problem now located inside people and outside our influence, we feel as if we have no choice but to act the way we do – say, firing someone, or quitting, or reprimanding someone, or withdrawing – all things we’d prefer not to do, but feel compelled to do because the other person has left us little choice. In the end, what we fail to see – or even consider – is that we are often reinforcing in others the very behavior we find difficult.

I witnessed an especially telling example of this perspective at a pharmaceutical company, when two executives got into a debate over who was to blame for their division’s poor performance. It started when Peter Naughton, the division’s new CEO, confronted Tom Bedford, the division’s VP of research and development. Listen in as Naughton launches the debate:

Naughton: So now the question is: To what extent is R&D going to make the really difficult choices? Because one thing is clear: We can’t just keep adding and adding costs to R&D.

Bedford: We’ll start looking at that next month. But actually, I think we’ve got to revisit [corporate’s] strategy first. Our competitors see a very different future than the one corporate imagines for us. That’s the big problem. They’re spending fortunes and putting down bigger bets than we’re able to—

Naughton: —[Interrupting] Hang on a second! If we’re honest about this, our problem is that we were late waking up to what we might, could, and should do. There is an issue, but the issue is, we were late. Many of these questions should have been tackled three years ago. They weren’t. It was simply, “Oh, let’s toss another three million into the annual R&D budget.” That’s hardly a strategic answer.

Notice what happens in this opening exchange, in which Naughton defines and Bedford accepts the terms of the debate: who’s to blame for the division’s woes. Naughton says it’s the division; Bedford says it’s corporate. Now what? With the two immediately at an impasse, Naughton raises the stakes with an appeal to honesty — “If we’re honest about this, our problem is that we were late” — as if his view is the only honest view to take. Although this could easily put Bedford in a bind (either admit blame or appear dishonest), Bedford forges on, undeterred:

Bedford: [Looking down, shaking his head] I’m not complaining. I’m—

Naughton: [Interrupting] We can’t just chalk it up to corporate isn’t supporting us.

Bedford: [Looking up, raising his voice] But there’s no criticism in my statement!

But there clearly is criticism in Bedford’s statement. He’s just said that they need to revisit corporate’s strategy. So what would lead Bedford to deny that he’s criticizing corporate when he’s clearly doing so? One possibility is that it allows him to appear honest (he’s not criticizing or blaming anyone) while still not accepting blame himself. Naughton doesn’t buy it:

Naughton: [Emphatically] You’re saying, “It’s not our fault in R&D. If only corporate would open their eyes, they would have seen all this.” But if you look at how long it’s taken us, you can’t blame corporate—

Bedford: —And if you look at the history of this business, we all know where blame can be placed, and it is on many heads [glares at Naughton].

Barred from blaming corporate yet unwilling to blame himself, Bedford eludes Naughton’s grasp once again, this time by placing blame on many unnamed heads. This move, which reveals the hopeless nature of their debate, prompts Naughton to deny having launched it in the first place.

Naughton: [Sighing] I wasn’t trying to assign blame. I’m merely stating the reason the organization is behind is because we’ve been late.

Bedford: And I’m merely saying that we’ve been late because we have yet to convince our corporate masters that the future is different than the one they see.

Now we have Bedford and Naughton both placing blame, while claiming they’re not: They’re merely “stating” this or “saying” that. This joint denial makes it much harder to continue placing blame, which leaves Naughton no choice: He must close down the debate.

Naughton: Then let it start here [jabbing the table with his index finger]. We haven’t convinced ourselves yet. We’re the ones who need to figure out what we’ll invest in and what we’ll cease to do. Until we do that, we can’t possibly make a compelling case for support. [Putting his papers aside] Next item?

Naughton has the last word, but he convinces no one, least of all Bedford. The more Naughton pushes, the less responsibility Bedford takes — and not just for the division’s failure: He won’t even take responsibility for not taking responsibility!

These are the games we play to navigate around assumptions that make it hard to say what we think, because what we think is so problematic. When we assume that one person is responsible for outcomes we don’t like, and that this person is either mad or bad for causing them, all we do is compel that person to defend himself. If that person then also assumes that only one person (or side) is at fault, the best he can do is throw the blame right back at us.

Unless people seek to understand how they are both contributing to outcomes no one likes, they will be forever caught in the same paradoxical game in which the more individual responsibility is sought, the less individual responsibility is found.

So what’s the alternative? As unlikely as it may seem, the glimmers of one can be found in Bedford’s notion of blame falling on many heads. What makes this notion problematic is that the heads are unnamed and the purpose is to blame, not to understand. But what if Bedford and Naughton had sought to understand how the heads of both corporate and division had contributed to results neither liked? Perhaps they would have discovered how their waiting for the other to act had made it harder for either to do what they needed to do to improve the division’s performance. That is, with the division waiting for corporate to place bigger bets before focusing, and corporate waiting for the division to focus before placing bigger bets, and neither of them looking at their joint responsibility, they together created an impasse that prevented them from improving the division’s performance.

Most people I know believe deeply in personal responsibility, recognize how self-defeating it is to blame others, and are acutely aware when others are doing it. But curiously, few people are aware when they’re doing the same thing. Indeed, in the heat of the moment, most us believe that, in this one case, the other really is to blame for our substantive impasse or our relationship troubles, and we ourselves have little choice but to act the way we do.

Only in the interactions of the most mature leaders do you see a perspective based on a different set of assumptions. These assumptions, which constitute what I call the relational perspective, focus on mutual responsibility and stress the importance of relationships. The next section shows what these assumptions look like in action.

The Relational Perspective

When World War II brought Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt together, they were a study in contrasts: Roosevelt, secretive; Churchill, transparent. Roosevelt, calculated and at times manipulative; Churchill, expressive and at times impulsive. Roosevelt, intent on keeping the United States out of the war; Churchill, equally intent on bringing the United States into the war. Roosevelt, a constant critic of colonialism; Churchill, a steadfast defender of the British colonial empire. Roosevelt, convinced that a leader ought to keep his ear to the ground of popular opinion; Churchill, equally convinced that a leader ought to get out in front and shape popular opinion. And yet over the course of the war, as Jon Meacham recounts in Franklin and Winston: An Intimate Portrait of an Epic Friendship, Random House, 2003, they were able to forge an alliance based on a common purpose and what Meacham calls an “epic friendship.”

Of the many things they did to build that friendship, one thing Meacham mentions stands out: “They always kept the mission — and their relationship — in mind, understanding that statecraft is an intrinsically imperfect and often frustrating endeavor.”

When it came to that mission, Roosevelt and Churchill saw and cared about very different things, triggering disagreements over a wide range of topics. How they handled these disagreements is striking. Instead of discounting each other’s views or assuming the other just didn’t get it, they engaged in hours of debate, seeking to persuade and to understand. They never denigrated the other’s interests or beliefs; they took them into account and sought to address them whenever they could. And if either of them did things to make matters worse, more often than not they looked to the other’s circumstances, not his character, to understand why, and they repeatedly offered a helping hand.

The relational perspective focuses on mutual responsibility and stresses the importance of relationships.

This way of handling their differences became apparent early on, when Churchill repeatedly petitioned Roosevelt to enter the war, and Roosevelt just as repeatedly refused. With 90 percent of Americans opposed to the war, Roosevelt sought every way possible to support Britain short of sending troops. It wasn’t enough. France quickly fell, and Britain alone was left fighting the Nazis. Roosevelt came under attack in the British Parliament for refusing to enter the war. The one person who came to his defense was Churchill.

“[America has] promised fullest aid in materials, munitions,” Churchill began at a closed session of Parliament on June 20, 1940. Calling the aid a “tribute to Roosevelt,” he then alluded to America’s upcoming presidential election, saying, “All depends upon our resolute bearing until Election issues are settled there. If we can do so, I cannot doubt a whole English-speaking world will be in line together.”

Given Churchill’s political pressures and beliefs, it would have been easy for him to join in Britain’s outrage or to accuse Roosevelt of being a slave to public opinion. But he didn’t. Instead he pointed to the circumstances that impinged on Roosevelt’s choices, and instead of pressing Roosevelt to deliver something he couldn’t practically do, he made it easier for Roosevelt, believing that this would be more likely to bring them in line after the election.

Roosevelt took a similar approach after the fall of Singapore, the jewel of the British empire. In an effort to soften the blow, Churchill gave a radio address in which, among other things, he referred to American sea power as having been “dashed to the ground” at Pearl Harbor. Washington’s inner circles complained that Churchill had just blamed the U. S. Navy for the fall of Singapore.

Roosevelt, waved away their complaints and, picking up a pen, wrote Churchill a note. “I realize how the fall of Singapore has affected you and the British people,” he began. “It gives the well-known backseat drivers a field day… I hope you will be of good heart in these trying weeks because I am very sure that you have the great confidence of the masses of the British people. I want you to know that I think of you often and I know you will not hesitate to ask me if there is anything you think I can do.”

Because Roosevelt and Churchill understood that their relationship would have a decisive impact on the success or failure of their mission, they gave it the same strategic attention they gave every other aspect of the war. All told, they met nine times between 1941 and 1945 in a range of different locales from Canada to Casablanca to Iran. In between, they exchanged countless wires, letters, and phone calls on everything from their families’ well-being to their flagging spirits to matters of war.

At a dinner during World War I where Roosevelt met Churchill for the first time, the former remarked on “the importance of personal relationships among allied nations.” When Churchill was appointed first lord of the Admiralty in 1939 — sent eight days after Hitler invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, nine months before Churchill became prime minister, and two years before the United States entered the war — Roosevelt wrote,

My dear Churchill, It is because you and I occupied similar positions in the World War that I want you to know how glad I am that you are back again in the Admiralty. Your problems are, I realize, complicated by new factors but the essential is not very different. What I want you and the Prime Minister to know is that I shall at all times welcome it if you will keep me in touch personally with anything you want me to know about.

Once Churchill became prime minister, the two men went to great lengths to meet face-to-face. In August 1941, four months before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and six weeks after Germany invaded the Soviet Union, they traveled by ship in secret and at great risk to Placentia Bay, Newfoundland. There, aboard their two vessels, through days of talking, drinking, and smoking together, they forged a common bond and a common purpose.

Churchill left their initial encounter believing that Roosevelt’s “heart seemed to respond to many of the impulses that stirred my own,” while Roosevelt’s son, Elliot, observed, “My experience of [my father] in the past had been that he had dominated every gathering he was part of; not because he insisted on it so much as that it always seemed his natural due. Tonight, Father listened.”

But basic differences also emerged. “The two disagreed,” Meacham recounts, “and would for the rest of the war, about colonialism… setting the stage for a long-running source of tension between the two men.” And this was not their only source of tension — or their most difficult one.

As the war neared its end, Roosevelt and Churchill disagreed vehemently over how to handle Premier Josef Stalin and the Soviet Union. In their first three-way meeting, Roosevelt sought to charm and placate the premier in hopes of securing his support for a United Nations, while Churchill took a tougher stand, fearing they would face Soviet aggression after the war. Though Churchill would eventually prove prescient, at that meeting, it was Churchill, not Stalin, who played the odd man out.

Unsurprisingly, during this time of constant tension, Roosevelt and Churchill’s relationship grew more contentious. In a steady stream of cable traffic, the two fought over how best to end the war and structure the peace. With Churchill intent on protecting Britain’s post-war place, and Roosevelt just as intent on advancing America’s interests, the two men argued fiercely. In their last fight, this one over whether they should try to beat the Soviets to Berlin, the two failed to reach agreement. In the end, Churchill conceded. Afterward he wrote Roosevelt a note to reassure him that there were no hard feelings: “I regard the matter as closed,” he wrote, “and to prove my sincerity I will use one of my very few Latin quotations, ‘Amantium irae amoris integratio est.’” Translation: “Lovers’ quarrels always go with true love.” A week later, their friendship came to an end with Roosevelt’s death.

Meacham writes, “For all the tensions, and there were many… there was a personal bond at work that, though often tested, held them together.” I would argue that the strength of that bond was a product of the way they saw and handled their most fundamental differences. When disagreements broke out and pressures mounted, they sought to understand how the other thought and ticked. And while neither man hesitated to advance his own views or interests, they were equally quick to ask about the other’s opinion and to listen with genuine interest. As a result, no matter how frustrated they became, they never reduced each other to a caricature. Instead they built an ever more nuanced and subtle understanding of — and appreciation for — each other as people and for each other’s views and beliefs.

Most important and most unusual, despite the many competing demands on their time and the geographic distance between them, Churchill and Roosevelt took great pains throughout the war to invest in their relationship. More than anything else, this investment — and their mutual willingness to make it — allowed them to find common ground in the face of basic differences and to withstand the vast uncertainties and pressures of war.

THE RELATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

Throughout, the two leaders illustrated a perspective built on a set of assumptions many leaders espouse but few enact (see “The Relational Perspective”). This perspective is based on a core belief best expressed by Karl Popper: “While differing widely in the various little bits we know, in our infinite ignorance we are all equal.”

This basic belief leads people to assume that we all see things others miss, that disagreements are inevitable and valuable, that those disagreements will at times cause frustration, and that people will be better off if they help each other build relationships that can handle those differences well, especially under pressure.

Reality Check: The Power of Relationships

Aware of it or not, we all tend to make two assumptions: behavior is caused by an individual’s disposition, and those dispositions are impervious to change.

We’re wrong, it turns out, on both counts.

All of us are exquisitely sensitive to experience and to circumstance. For decades now, one psychology experiment after another has shown that situations have far greater sway over people’s behavior than we think. Yet the belief that behavior is determined by disposition is so pervasive that psychologists call it the fundamental attribution error.

Even more intriguing is recent research conducted by genetic and family researchers. A number of them are discovering that our relationships have the power to either amplify or modify even genetically based predispositions. Take, for example, a twelve-year study of 720 adolescents led by family psychiatrist David Reiss. It found that relationships within a family affect whether and how strongly genes underlying complex behavior get expressed.

“Many genetic factors, powerful as they may be,” says Reiss, “exert their influence only through the good offices of the family.” Some parental responses to genetic proclivities – say, toward shyness or antisocial behavior — exaggerate traits, while others mute them. In other words, to have any effect, genes must be turned on, and relationships are the finger that flips the switch.

Behavioral geneticist Kenneth Kendler of the Medical College of Virginia describes just how they flip this switch:

Family is like a catapult. Kids with a difficult temperament can be managed and set on a good course, or their innate tendencies can be magnified by the family and catapulted into a conduct disorder… A child with a difficult temperament brings on parents’ harsh discipline, verbal abuse, anger, hostility and relentless criticism. That seems to exacerbate the child’s innate bad side, which only makes parents even more negative, on and on in a vicious cycle until the adolescent loses all sense of responsibility and academic focus.

This power of relationships to shape behavior doesn’t stop in childhood. If we’re wired to do anything, it seems, we’re wired to learn. “Learning is not the antithesis of innateness,” says Gary Marcus in The Birth of the Mind. “The reason animals can learn is that they can alter their nervous systems based on external experience… experience itself can modify the expression of genes.”

Reams of research suggest that the brain continues to change in response to experience. Even adult brains are proving more mutable than most people think. Indeed, it’s looking more and more that our genes are continually working together with our environments — and most important, our relationships — to define and redefine who we are by structuring and restructuring our brains.

All this research adds up to one important conclusion: Our assumptions about individuals are quite simply wrong. Even so-called “difficult” people aren’t innately or irrevocably mad or bad. The relationships we build with others have the power to bring out the best or the worst in all of us. It’s the relationship we should be focusing on, not on individuals alone and in isolation.

This article is excerpted from The Elephant in the Room: How Relationships Make or Break the Success of Leaders and Organizations (Jossey-Bass, 2011).

Diana McLain Smith is Chief Executive Partner at New Profit Inc. She has also served as a partner and thought leader at the Monitor Group, a global management consultancy, and she is co-founder of Action Design, specializing in professional and organizational learning. Diana earned her master’s and doctoral degrees in consulting psychology at Harvard University.