The latest casualty of the changes sweeping through corporate America is the lifetime employment contract — the implicit agreement that provided employees with economic security in exchange for doing whatever work was necessary to keep the enterprise running. According to Fortune magazine, the new employment deal goes something like this: “There will never be job security. You will be employed by us as long as you add value to the organization, and you are continuously responsible for finding ways to add value. In return, you have the right to demand interesting and important work, the freedom and resources to perform it well, pay that reflects your contribution, and the experience and training needed to be employable here or elsewhere” (‘The New Deal: What Companies and Employees Owe One Another,” Fortune, June 13, 1994).

This radical restructuring of the employment contract comes at a time when businesses arc facing a whirlwind of challenges. The nature and scope of changes such as downsizing, re-engineering, and new competitive rules suggest that they are in fact part of a larger trend toward an emerging new model of corporate organization. But what will be the role of workers and management in this new organization? The current upheaval offers the perfect opportunity to create not just another contract, but a new covenant for employment — one based on the concept of stewardship rather than patriarchy.

A New Employment Covenant

Peter Block, author of the book Stewardship (Berrett-Koehler, 1993), describes stewardship as “the willingness to be accountable for the well-being of the larger organization by operating in service, rather than in control, of those around us. Stated simply, it is accountability without control or compliance.” In Stewardship, Block offers a vision of a new type of organization based on a fundamental belief that all employees should be treated as mature adults who can be held responsible for themselves and their actions.

This new model strives to create an environment in which people can fully participate and contribute to the goals of the larger organization. Such a commitment goes beyond the traditional concept of an employment “contract” — it would be more accurately called a “covenant.” While a contract tends to focus one’s efforts on keeping within the letter of the law and preventing what we do not want (patriarchy), a covenant emphasizes operating in the spirit of the law and focusing on creating what we do want (stewardship).

At first blush, the new employment covenant sounds almost utopian — after all, who can argue with people taking their future into their own hands, finding or creating interesting work for themselves, and becoming responsible for their own careers? These ideas have the makings of a great vision, but there are fundamental questions that need to be addressed: What will the new covenant look like, how will it be implemented, and perhaps most importantly, who has the power and responsibility to make it a reality?

Leadership and Governance

At the heart of the new employment covenant is the issue of governance—how we distribute power, privilege, and control. If we are truly committed to bringing about this new covenant, we need to work to create fundamental structural changes to support it.

The governance structures in most organizations still treat people as if they need to be taken care of and “controlled,” either because they are incapable—for reasons of both individual maturity and organizational complexity—or simply untrustworthy. The old employment contract had at its foundation an implicit assumption that our leaders somehow knew more than we did, so we could trust them to make the right choices and take care of us. In return we gave them the authority to make decisions on our behalf. But, as Block points out, “When you ask someone to take care of you, you give them at that moment the right to make claims on you.”

By following this implied contract, we have colluded in sustaining a system in which we give up individual initiative, responsibility, and accountability in exchange for “guaranteed” rewards. But the new covenant challenges this basic belief. According to Fortune, “For some companies and some workers, [the new covenant] is exhilarating and liberating. It requires companies to relinquish much of the control they have held over employees and give genuine authority to work teams…. Employees become far more responsible for their work and careers: No more parent-child relationships, say the consultants, but adult to adult.”

°Shifting the Burden° in Reverse

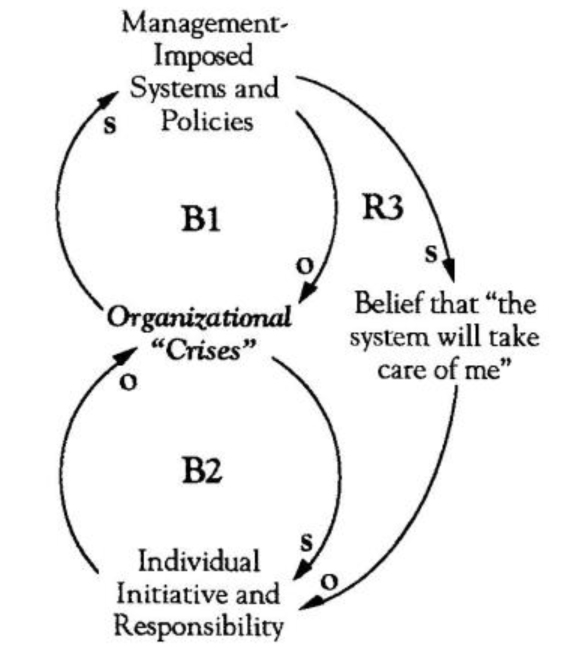

From a systemic viewpoint, the new covenant has the potential to reverse an entrenched “Shifting the Burden” structure. In most companies, management-imposed systems and policies have been the predominant way of dealing with organizational crises (BI in “When Policies Turn into Parenting”). This has led to the continual underdevelopment of individual initiative and responsibility (B2), which, over time, leads to more organizational crises and further justifies the need to develop more systems and policies to help “tend the flock.”

Through this process, the belief among employees that “the system takes care of me” increases (R3), which further undermines individual development. The burden of responsibility is “shifted” to those in higher positions through well-intentioned, seemingly progressive human resources policies. It is a simple extension of the familiar parenting model.

Recognizing that we are caught in this structure is one thing; reversing the dynamic, however, is a more difficult challenge. If the new covenant is to take hold, managers must be willing to reflect on their own role in the system and consider alternative roles beyond that of caretaker and controller. Otherwise, the new employment covenant will become (or will be interpreted as) simply another exercise of power, with those at the top of the organization imposing rules on everyone except themselves. If that is the case, then the changes are likely to be neither effective nor deep. As Block states, “unless there is also a shift in governance… [change] efforts will be more cosmetic than enduring.”

Fear of Losing Control

One of the particular issues managers must face is the fear associated with letting go of control. This may not stem from a lack of trust in people, per se, but from a mistrust of our own understanding of the complexities that we manage. That is, because we don’t trust the overall capability of the enterprise as a system, we act in ways that treat people as if they are themselves untrustworthy. This insecurity drives us to over control, rather than allow individuals to exercise their best judgment.

According to Block, stewardship requires the belief “that with good information and good will, people can make responsible decisions about what controls they require and whom they want to implement them.” Having good information and good will may not be enough to make intelligent decisions, however, if we are not aware of the larger context in which they are being made.

°Tragedy of the Commons° Lessons

Without a global perspective, it is easy to make decisions that are beneficial to certain parts but that sub-optimize the whole. The “Tragedy of the Commons” structure offers many examples of this situation. The main lesson of this archetype is that the leverage does not lie at the individual level.

“Tragedy of the Commons” plays itself out wherever there is a common resource (people, physical space, budgeted dollars, etc.) that must be shared by equivalent players (those with equal power in the organization). Each person or department tries to maximize their use of the resource. When the sum of their requirements exceeds the resources that are available, there is no incentive for anyone to give up their piece. In this case, good information and good will alone are not enough to make the best decisions for the organization; a higher authority is needed.

This does not automatically mean that a “boss” steps in and makes the decisions for the teams. Instead, what is needed is an appropriate governance structure that everyone agrees to follow in advance of any specific decision having to be made. This could take the form of a set of criteria against which individual needs are weighed, a review board that is charged with maximizing the organizational use of a resource, or a system of checks and balances that recognizes when divisional needs must be sacrificed for the benefit of the whole company. The role of a leader, in these cases, is not to dictate from the top, but to help identify and create the appropriate governance structures.

Changes at Multiple Levels

So how can we make the new employment covenant a sustainable reality? The first step in this process is to be vigilant about how day-to-day decisions are being made. We cannot, in the name of efficiency, override the spirit of partnership and drive the process without full participation. All those being affected by the new covenant must be involved in mapping out the new structures and policies from the start. Getting everyone involved will require significantly more time than a traditional top-down “roll out,” but in the end, it may be more efficient and effective. If everyone’s participation is important to achieving the goal (which is the purpose of shifting responsibility back to the individuals), then anything that bypasses anyone’s involvement will be less than effective.

The second step is to examine the structures that are embedded in our organizations as a product of patriarchy (such as “Shifting the Burden” dynamics) and begin to clarify the challenges of moving to a structure that is based on partnership. After decades of living with patriarchy, people may require some adjustment time before they can fully step into the new model.

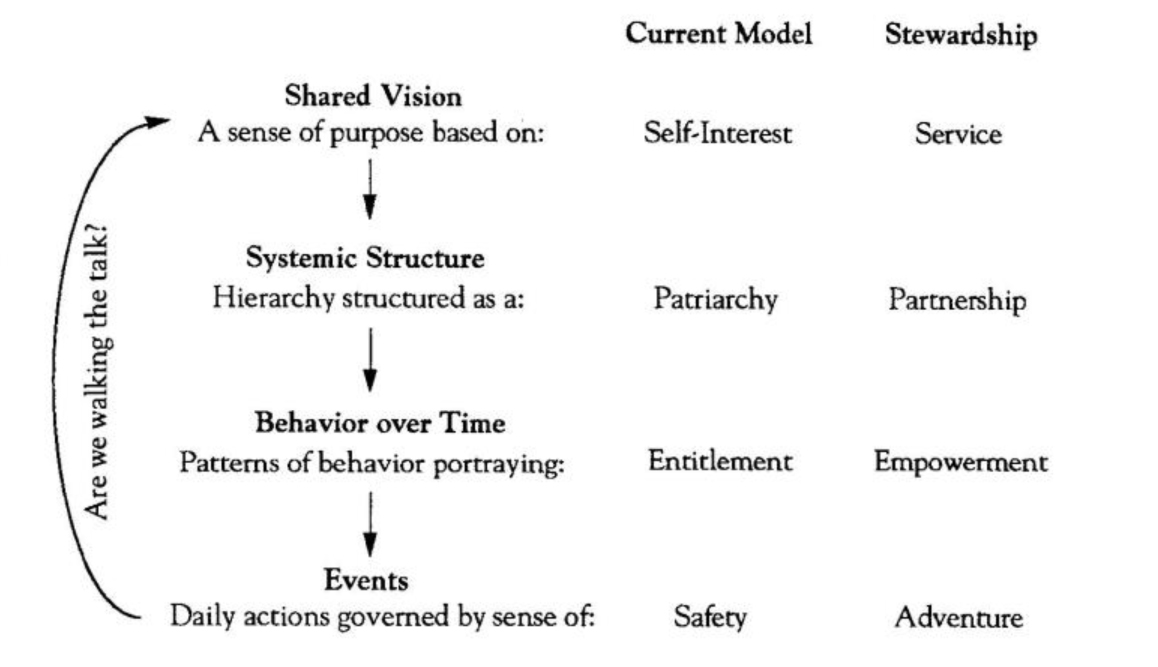

Most importantly, changes must happen at multiple levels simultaneously in order to be significant and enduring (see “New Model for Leadership”). The vision of stewardship is rooted in a shared sense of purpose that is based on choosing service over self-interest. This vision and its underlying values and beliefs will, in turn, guide the understanding of current reality and the creation of new systemic structures that will help translate the ideals into reality.

When Policies Turn into Parenting

The new employment covenant is working to reverse an entrenched “Shifting the Burden” structure, in which the burden of responsibility has “shifted” to those in higher positions.

But it is at the level of everyday events and patterns of behavior that we will demonstrate whether we are serious about making fundamental changes. The congruence between daily actions and shared vision will answer the question, “How serious are we about walking the talk?” If daily actions are governed by efforts to maintain safety, then everyone will hedge their bets and the dynamics of entitlement and patriarchy will likely continue. If, on the other hand, there is a sense of adventure and risk-taking, then empowerment will be a natural reinforcing by-product of such actions.

The Stewardship Challenge

Stewardship can spring up anywhere in an organization. Stewardship is leadership in the moment, not leadership by position. This means that we should not only look up the organizational chart for leaders, but across and down as well. Hierarchy then becomes less of a system of power and control and more of what it should be — a system of organization that makes distinctions between different types of work and responsibilities. Stewardship ultimately challenges us as individuals to make those choices and then live by them, as we acknowledge that the responsibility for leadership lies squarely on everyone’s shoulders.

Stewardship (Berreu-Koehler, 1993) is available through Pegasus Communications, Inc. (617) 576-1231.

New Model for Leadership