Why is it that new organizations start up with great enthusiasm, achieve success in the marketplace, and, just when everything seems to be going well, begin to self-destruct? What happens in organizations as part of the growth process that almost inevitably leads to dissatisfaction, even though we have been successful in achieving what we set out to accomplish? And can senior executives and middle managers — and the consultants and researchers who support them — glean lessons from these dynamics so as to avoid them in their own organizations?

Having worked with a number of new enterprises and groups within large organizations that have achieved success and rapid organizational growth, we have come to believe there is a dark side of success. In years of exposure to these kinds of situations, we have seen patterns that appear independent of the individuals involved, in which accomplishment leads to dysfunction, and accolades give way to frustration and dissatisfaction. If ignored by senior executives and management teams, these patterns can lead to the spiraling decline of the organization. If, on the other hand, leaders anticipate and deal with these dynamics in a timely and disciplined way, they can lead their organizations to sustained success on both a business and a human level.

In his recently published book DEC Is Dead, Long Live DEC: The Lasting Legacy of Digital Equipment Corporation (Berrett-Koehler, 2003), MIT management professor emeritus Ed Schein identifies a number of “invisible” consequences of the rapid growth of DEC in the 1960s–1980s. These insights emerged from his 26 years of consulting with the CEO and senior management team. In cases we have studied, we also recognized some of these same consequences in their early stages.

As organizations grow and disperse geographically, four things tend to happen.

What happens in organizations as part of the growth process that almost inevitably leads to dissatisfaction?

- First, employees lose familiarity with one another, and work relationships become less predictable and more difficult to manage.

- Second, open communication both upward and laterally in the organization becomes more challenging and time-consuming.

- Third, the organization as a whole finds it difficult to achieve strategic focus.

- Finally, anxiety grows among executives and employees alike.

These problems can escalate over time and, left unaddressed, bring even the most vibrant organization to its knees.

So how do you identify and constructively deal with these issues before it’s too late? A recent case study illustrates some of what we believe are generic systemic patterns in rapidly growing organizations that are variations of the “Limits to Growth” systems archetype, as well as potential interventions for managing the challenges of success.

Growing Challenges

A highly successful nonprofit organization had just opened a second office and hired new employees to serve the dramatically increasing customer base. Shortly after, a new president/COO came on board to help the CEO deal with the growing organizational size and complexity.

As the new COO worked toward creating a strategic plan, she became increasingly uneasy. She saw problems regarding:

- The capacity of managers to deal with the challenges of a larger and more complex organization;

- Negative and sometimes hostile attitudes of some senior staff members;

- Executives who used the excuse of not understanding the organization’s goals as a license to do their own thing; and

- The unwillingness of some of the veterans to deal with the process and human implications of growth.

In interviews we conducted with the COO, she told us of her frustration and anger at several members of her management team. She had spent many unproductive hours trying to work with them, to no avail. She had reluctantly reached the conclusion that they were having a negative impact on the rest of the staff as well and would have to go.

At the invitation of the CEO and COO, we began to investigate the situation. We conducted a series of interviews with the senior management team and identified five key issues:

- Lack of clarity and agreement about the meaning of their shared vision;

- Employees’ feelings of being excluded from the team and lack of understanding regarding the needs of the larger organization;

- Competition and turf battles resulting in part from the opening of the second office;

- Lack of clarity and enforcement regarding recent delegation, empowerment, and accountability decisions; and

- Inadequate management training in the skills required to lead a more complex and stratified organization.

What was it that caused all of these issues to surface at about the same time in an apparently well-run and successful organization? A systemic view of the situation, developed by participants in three two-day “Learning Labs” over a six-month timeframe, provided some provocative insights. Participants in the Learning Labs included the CEO, COO, and all senior managers. By working with causal loop diagrams of the dynamics they described, the group was able to identify some leverage points for change and ultimately reverse the negative dynamics that had begun to dominate the organization.

SUCCESS ENGINE PART I

The Engine of Success

Our initial task was to try to understand what had enabled the organizazation’s growth and success in the recent past. Once we clarified the core process the management group viewed as responsible for their earlier accomplishments, we could explore ways for them to redirect their efforts and sustain that success into the future.

In this case, the group identified clarity of goals as having played an essential role in the past. Because of its relatively small size in earlier years, all employees participated in clarifying the organization’s objectives. With clear goals, the organization was able to effectively target its resources toward high-leverage activities. Identifying such focused activities also allowed employees to align all their efforts — from mission through strategy to final results — for consistent outcomes. This alignment ultimately led to high levels of performance. And once people saw the tangible benefits that resulted from having clear goals, they were even more willing to invest time and energy in the process (see “Success Engine Part I”).

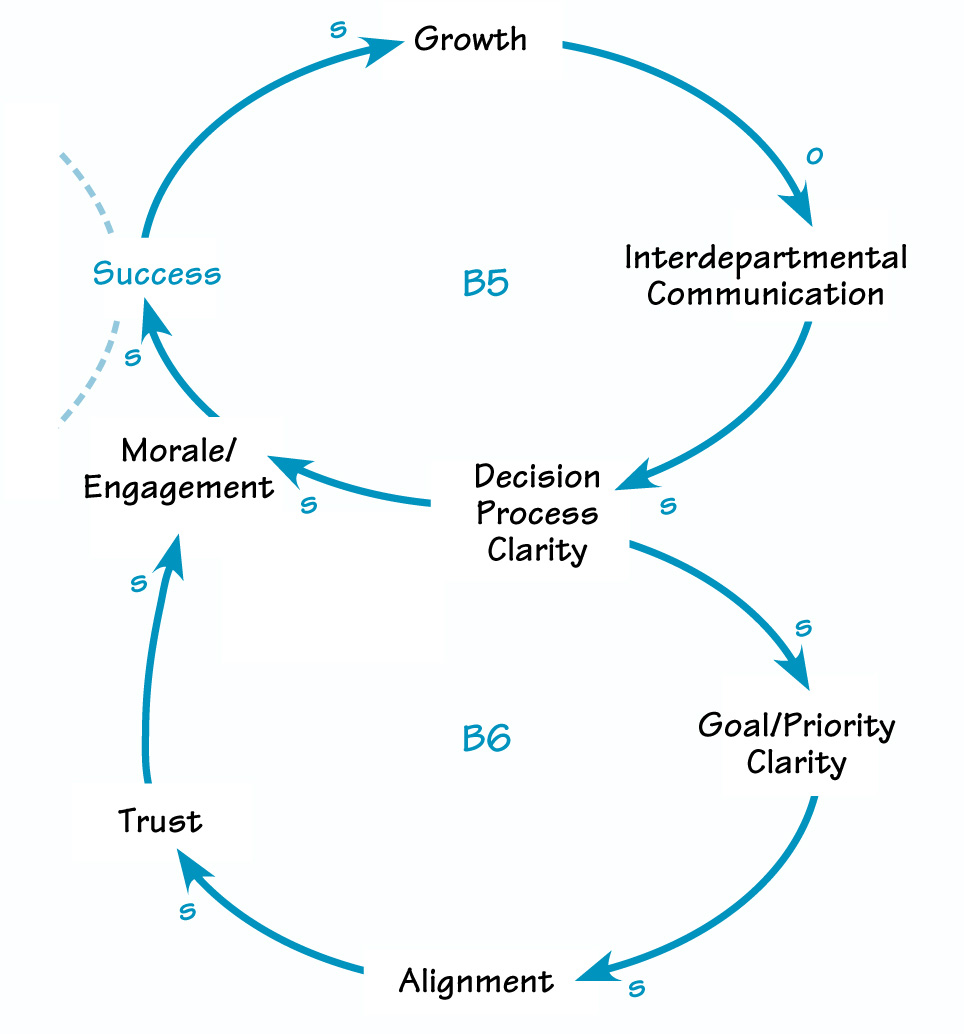

With the organization’s rapid growth, communication among business functions became more difficult, and senior managers and employees had come to hold widely varying interpretations of what the goals of the organization actually meant. The management team realized that clarifying goals and getting organizational alignment once again would have a positive impact on employee morale and teamwork.

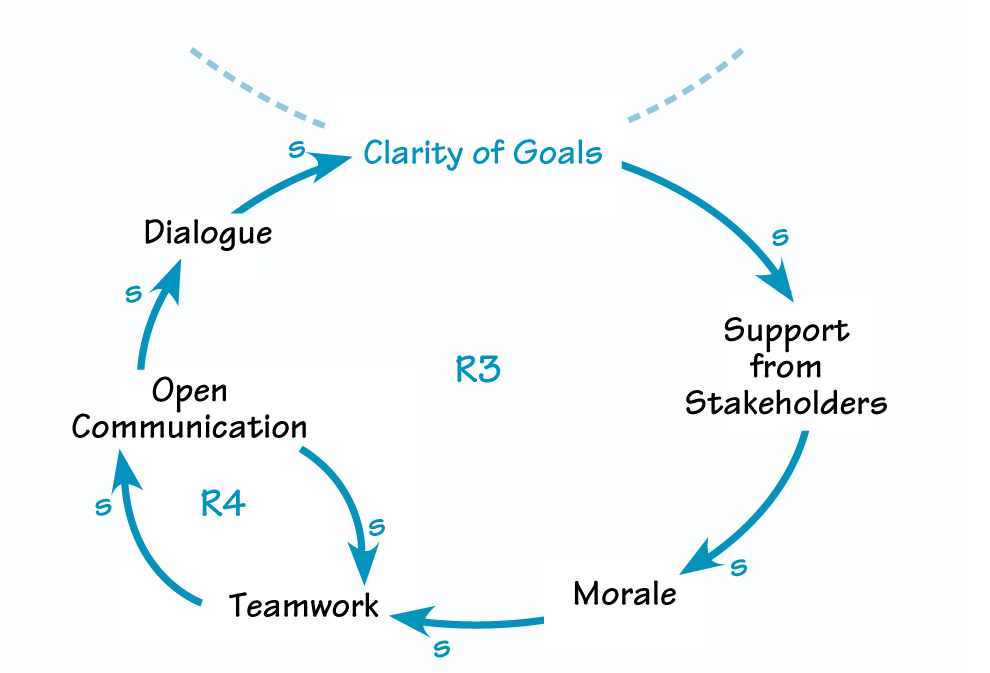

SUCCESS ENGINE PART II

In addition, with clear goals and a compelling mission, stakeholders, including board members, healthcare providers, and members of third-world governmental agencies, would feel more committed to the effort. Increased support from stakeholders would help to boost employee morale. The team believed that when people feel optimistic about their organization’s prospects, they can more productively engage in teamwork and feel more comfortable engaging in open, honest communication. Candid communication and improved teamwork then permit the deeper dialogue that leads to even greater clarity about shared vision and goals (see “Success Engine Part II”).

The management team came to the conclusion that, by making the mission and goals absolutely clear, consistent, and compelling, they could ensure that each employee knows how their everyday actions contribute to overall organizational success. Workers could also plan their activities with total focus, avoid any projects or activities that do not contribute value, and prioritize the rest based on their level of contribution to organizationwide objectives. Through the causal loop diagrams, the team was able to see how they had created an engine for growth and success in the past, and gained confidence that they could do so again in the future.

THE DARKER SIDE OF GROWTH PART I

The Dark Side of Growth

Having come to an understanding of how their organization could operate effectively, the management team then focused their energies on how the system was currently operating and what was impeding or could impede their progress. They recognized that there is in fact a dark side to growth that comes with success.

As the team discovered, as growth continues, functions and departments become larger in size and more specialized in their activities. Consequently, they tend to become differentiated from each other, and communication between and among them becomes more difficult than when the organization was smaller (see “The Darker Side of Growth Part I”).

THE DARKER SIDE OF GROWTH PART II

As communication and understanding decreases, workers find it more challenging to understand how, why, and by whom decisions are made. Morale begins to decrease; many employees become less engaged than previously; and the organization’s success is imperiled.

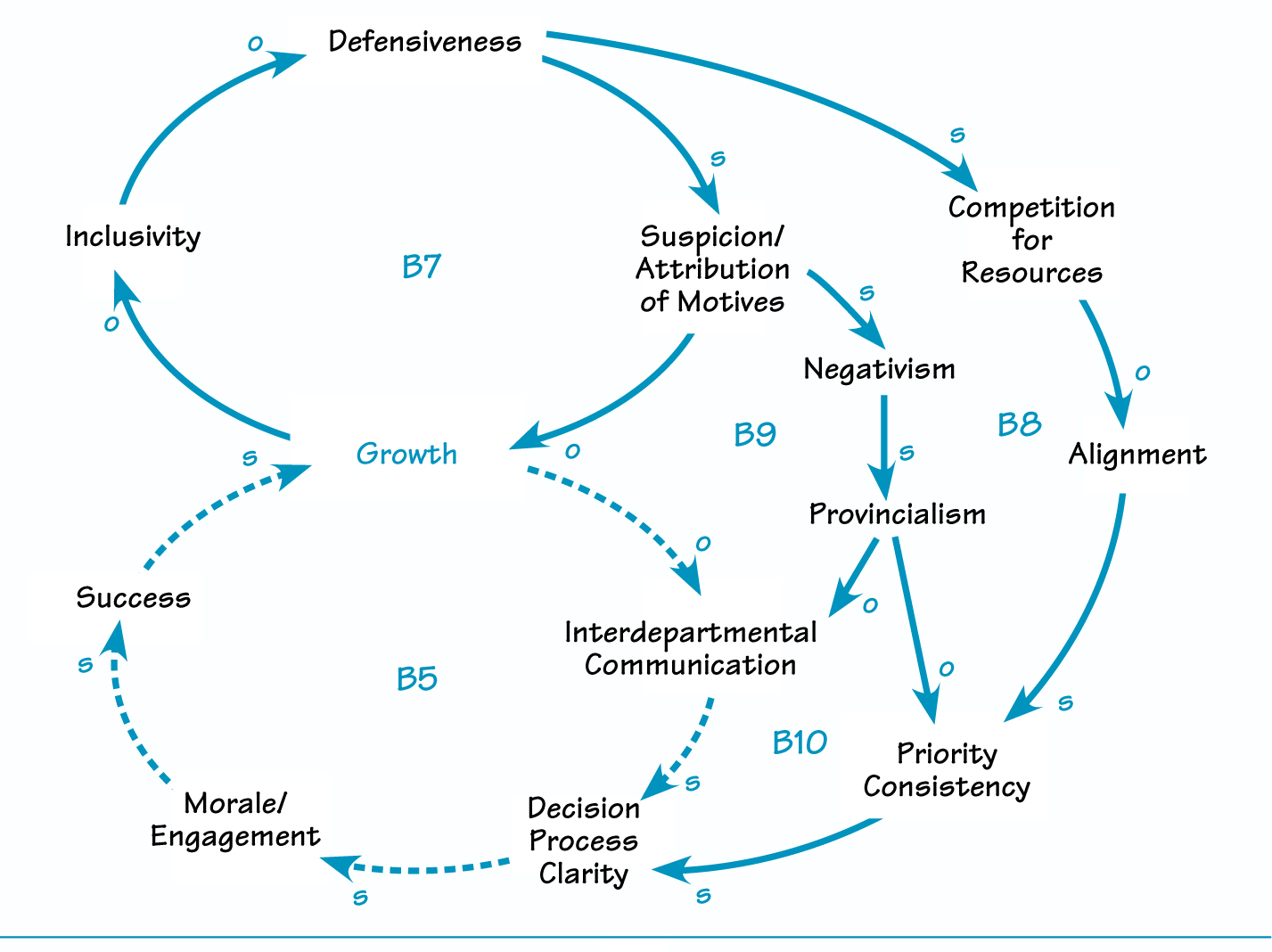

In addition, as the decision-making process becomes murkier, the lack of clear shared goals and priorities reduces the level of alignment in the organization and erodes trust. For when we can no longer be sure that we want the same things as our managers or coworkers, how can we have confidence in our ability to work together? Reduced trust further reduces morale, engagement, productivity, and, in the long run, organizational success. As defensiveness and suspicion grow:

- Negativism and provincialism rise, which undermines interdepartmental communication even further and makes organizationwide support for decisions less likely.

- Actions taken to mitigate the negativism and provincialism cause people to focus on why decisions don’t work — the problem — instead of on what we can do together to meet our goals — the solution. Leaders’ efforts to respond to the defensiveness lead to inconsistencies in priorities, and drain time and energy.

- The perceived inconsistencies in priorities reduce alignment among employees, thereby increasing competition for resources and further boosting defensiveness and suspicion (see “The Darker Side of Growth Part II”).

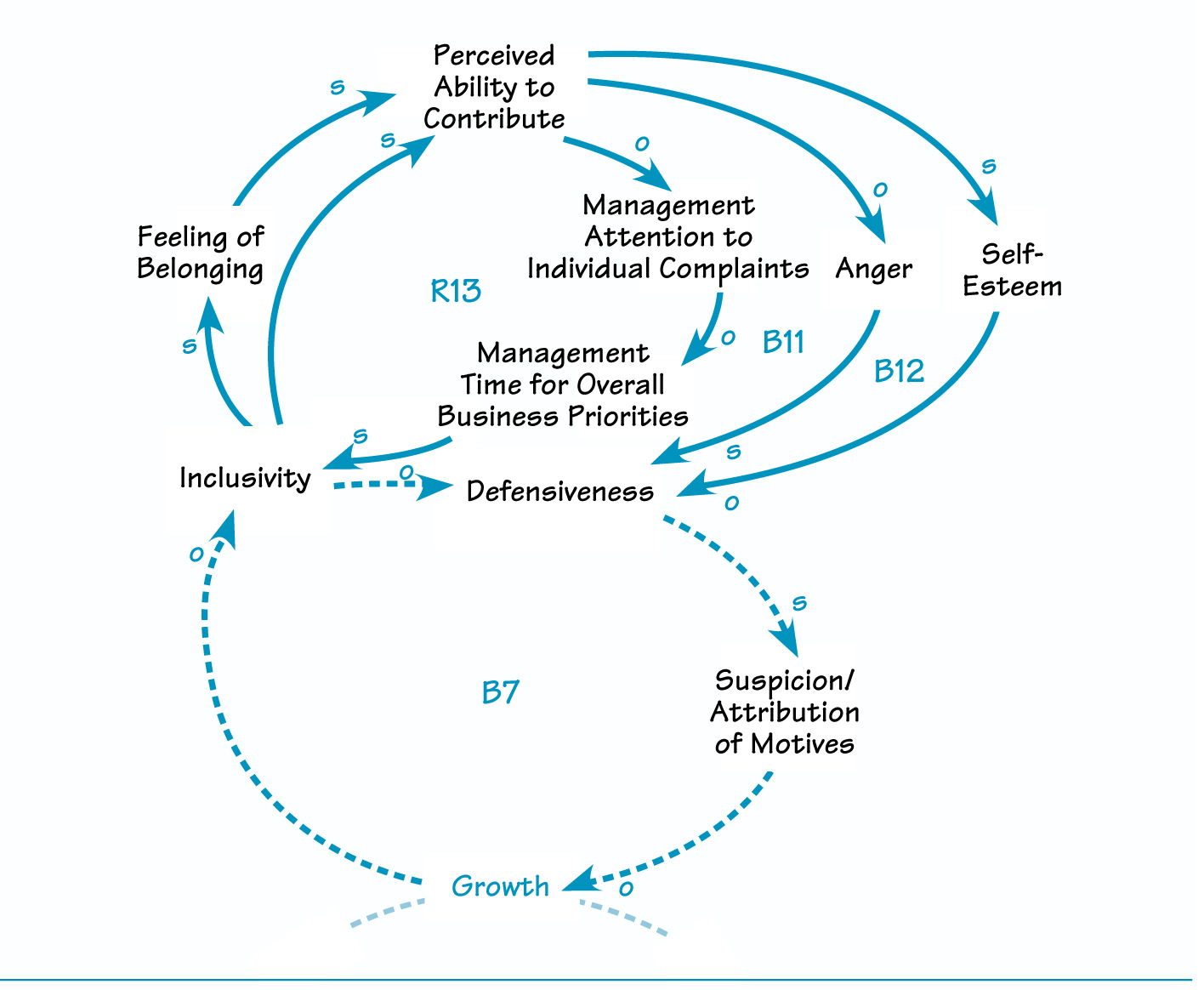

The Emotional Side of the Structure

From our interviews with the management team and conversations during the Learning Labs, we could see some significant emotional reactions that were resulting from the organization’s rapid growth. Levels of anger and defensiveness had begun to rise over time, while some workers’ self-esteem and feelings of belonging had plummeted. This pattern was consistent with our experiences in other organizations.

These problems again seem to stem from the fact that, as growth increases, groups can no longer include everyone in every decision. When people feel excluded, they become defensive and suspect others’ motives. They also begin to doubt their own abilities to contribute, which leads to anger in some and reduced self-esteem in others.

THE DARKER SIDE OF GROWTH PART III

According to Peter Meyer, author of Warp-Speed Growth: Managing the Fast-Track Business Without Sacrificing Time, People, and Money (AMACOM, 2000), many managers hold the fallacy that growth itself will resolve personnel issues and operational problems. Other managers may try to intervene with particular individuals, but the amount of time they spend bolstering vocal staff members may actually lead to less time spent on the priorities of the organization and a decreased sense of overall inclusiveness (see “The Darker Side of Growth Part III”).

The Outcomes

The development and analysis of the causal loop diagrams through interviews and the Learning Labs resulted in two important conclusions:

- The problems the organization was facing were not unique, but were the result of their very success and rapid growth.

- There were no villains in the story, only people trying to do their best in a systemic structure that generated some unfortunate and at times dysfunctional behavior.

The systems map indicated two key leverage points for immediate action: creating more clarity around the vision and goals, and improving the transparency and understanding of the decision-making process. The management team also identified a longer-term action: to hold “dialogues” on a regular basis to provide a safe mechanism for dealing with the emotional issues that surfaced.

In a rapidly growing organization where there is significant momentum and stress around accomplishing all the tasks associated with that growth, the decision itself to take time for reflection requires courage on the part of leaders.

With some initial reluctance, senior managers agreed to revisit the shared vision and goals to clarify any ambiguities and ensure that they were consistent with each other. They evaluated the outcomes expected from each goal, the metrics by which they could define success, and the method to be used to resolve conflicting priorities that might arise. During this process, inconsistencies and lack of clarity in the meaning of some of the objectives were revealed. The team also came to understand why some staff members responsible for specific goals were not aligned on priorities or action plans. In fact, in one dramatic example, at one point, the CEO confessed, “I guess I fudged that one to make it acceptable to all the board members.”

Once the group agreed on the goals, they worked to create a transparent decision-making process and establish a means for quickly disseminating decisions and their rationale to all employees. The team agreed to delegate decision-making authority to the level as close as possible to the actual work. In fact, instead of specifying what authority they would delegate, members created a “reservation of authorities” document, with a rationale for each decision-making authority that was reserved for senior management only.

The group communicated the results of this effort to all employees. As a whole, the organization launched an initiative to tie department and individual work assignments and performance reviews directly to the organization’s goals. Six months after completion of the project, the CEO and COO reported:

- They had a more cohesive management team.

- The decision-making process is working, and people are no longer complaining about not understanding what decisions were made or why.

- The organization is using performance reviews for each employee and an overall scorecard for senior management that tie directly to the organization’s goals.

- Employees are more aware of and skilled in surfacing mental models and understanding and dealing with different perspectives.</li.

- Teams occasionally slip back into a silo mentality and have not yet fully internalized the systems view, but they are continuing to work on doing so together.

The Issue of Inclusiveness

As we have shared this work with colleagues, we have been struck by the degree to which they report having encountered similar business and emotional dynamics in other organizations. It appears that many of these issues are, in fact, quite generic in situations where there is rapid organizational growth. Usually, senior managers fail to recognize and constructively deal with these patterns. Instead, the “blame game” often seems to prevail, thus precluding people from seeing and addressing situations from a systemic perspective to the detriment, and sometimes the demise, of the organization.

The issue of inclusiveness seems to be at the core of the emotional dynamics that arise in rapid organizational growth situations. People want to be a part of and contribute to their organization. When they feel thwarted, intense feelings and sometimes dysfunctional behaviors arise.

Executives and managers who subscribe to the myth that you can simply grow out of your problems do so at their own peril. As illustrated in the diagram, if organizations do not address these issues, a cycle of dysfunctional thinking, feeling, and acting can escalate and, over time, undermine success.

To avoid this drastic outcome, as happened in this case, senior managers first need to take the time to reflect on and understand the systemic structure in which they are operating. In a rapidly growing organization where there is significant momentum and stress around accomplishing all the tasks associated with that growth, the decision itself to take time for reflection requires courage on the part of leaders. Managing success then involves proactively clarifying and creating alignment around strategic goals, understanding the complexities of their systemic structure, and implementing a clear and transparent decision-making process along with an ongoing infrastructure to allow employees to voice and discuss their concerns. As shown in this case study, such steps can constructively transform an organization and enable continued growth and success.

CAUSAL LOOP DIAGRAMS

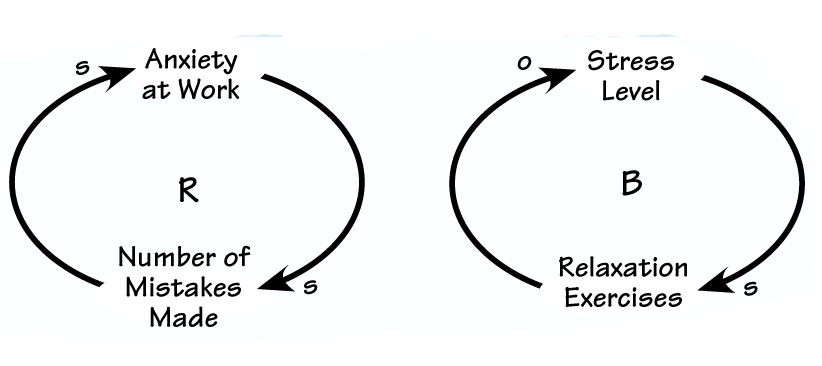

Each arrow in a causal loop diagram is labeled with an “s” or an “o.” “S” means that when the first variable changes, the second one changes in the same direction (for example, as your anxiety at work goes up, the number of mistakes you make goes up, too). “O” means that the first variables causes a change in the opposite direction in the second variable (for example, the more relaxation exercises you do, the less stressed you feel). In CLDs, the arrows come together to form loops, and each loop is labeled with an “R” or a “B.” “R” means reinforcing; i.e., the causal relationships within the loop create a virtuous cycle of growth or a vicious cycle that leads to collapse. (For instance, the more anxious you are at work, the more mistakes you make, and as you make more mistakes, you get even more anxious, and so on). “B” means balancing; i.e., the causal influences in the loop keep things in equilibrium. (For example, if you feel more stressed, you do more relaxation exercises, which brings your stress level down.)

CLDs can contain many different “R” and “B” loops, all connected together with arrows. By drawing these diagrams with your work team or other colleagues, you can get a rich array of perspectives on what’s happening in your organization. You can then look for ways to make changes so as to improve things. For example, by understanding the connection between anxiety and mistakes, you could look for ways to reduce anxiety in your organization.

Jeff Clanon is a founding consultant member and the director of partnership development for the Society for Organizational Learning. The Society (SoL) is a nonprofit, member-governed organization dedicated to building knowledge about fundamental institutional change through integrating research, capacity building, and the practical application of organizational learning theory and methods. SoL evolved from the Center for Organizational Learning at MIT, where Jeff was the executive director for five years. Fred Simon is an independent consultant, a founding member and member of the governing council of SoL, and an adjunct faculty member of the University of Michigan. He worked for Ford Motor Company for 30 years, where he pioneered new approaches to creating leadership at all levels. For more information about SoL, visit www.solonline.org.

NEXT STEPS

- Causal loop diagrams can be useful for casting light on all sorts of organizational dynamics, not just those associated with growth. If your organization seems caught in a chronic problem or cycle, work with a group to identify the relationships among key variables and possible interventions. For more information about causal loop diagrams, go to www.pegasuscom.com.

- If you think your organization is struggling with the challenges of growth, assemble a group of colleagues interested in exploring the problems through a systemic lens. Using the article as a starting point, examine the dynamics taking place in your own organization, and adapt the loops and/or story to match your particular circumstances. Pay particular attention to emotional issues, which are often overlooked.

- If your company isn’t currently facing growth-related issues, take preventative measures by ensuring that your “success engines” are operating smoothly. In particular, focus on enabling open communication and clarifying goals.

- When we think about organizational success, we often focus on the positive aspects — more money to invest in R&D and staffing, greater returns for investors, more of an impact on our market segment or community, and so on. We seldom take the time to explore the potential downside of success. With others from your organization, explore your assumptions about the good and bad aspects of growth and success.