Presence: Human Purpose and the Field of the Future (Society for Organizational Learning, 2004) represents a further evolution of many of the themes presented in Peter Senge’s classic The Fifth Discipline and its sequels. Written by Senge, Claus Otto Scharmer, Joseph Jaworski, and Betty Sue Flowers, this latest book takes a fresh, daring, and deeply felt leap into a space that can only be described as spiritual. It challenges us to ask both as individuals and in our organizational lives: What are we here for? What do we really care about? How can we serve an emerging future for our planet that averts environmental degradation and species destruction—including our own? To meet this awesome challenge, the authors say we must recognize and overcome a huge blind spot, one that “concerns not the what and how—not what leaders do and how they do it— but the who, who we are and the inner place or source from which we operate, both individually and collectively.”

A Shift in Awareness

In keeping with its theme of emerging futures, the book itself unfolds as a dialogue among the authors over a period of a year and a half (tellingly punctuated by September 11, 2001). Through a series of informal meetings, the four, all established organizational learning leaders and clearly also good friends, explore and enrich their understanding of the concept of “presence.”

It is not easy to say in a sentence or two what they mean by this word. The nature of presence is by definition experiential—something we feel and know in certain moments of insight, inspiration, and power. The basis for presence is awareness—being present in the moment to what is happening just now as opposed to our habitual ways of knowing, saying, and doing (which the authors refer to as “downloading”). But presence is more than merely being in the moment; it is also a deeper way of listening that allows us to let go not only of habitual ways of understanding the external world but also of our own fixed sense of identity. It loosens our desire for personal confirmation and control in favor of “making choices to serve the evolution of life.” Presence is a process of “letting come,” a way of “participating in a larger field of change” by which “the forces shaping a situation can shift from recreating the past to manifesting or realizing an emerging future.”

The authors acknowledge that this shift in awareness has much in common with traditional teachings and practices of Buddhism, Taoism, esoteric Christianity, Sufism, and indigenous cultures. They say that what is now needed in modern society is an account of how such a shift of awareness can be cultivated as a collective practice. Here lies the concept’s crucial connection to contemporary institutions, and it is here that Presence makes a fresh and provocative contribution to organizational learning theory. Organizations, from small working groups to—potentially—global companies, can be the fertile ground for cultivation of a life-serving collective transformation.

“Theory of the U”

The unfolding conversation presented in this book is by no means random or lacking in rigor. It is built around a strong theoretical skeleton that itself is based on research carried out over several years prior to and during the conversations. The research, conducted by Scharmer and Jaworski, consists of more than 150 probing interviews with “thought leaders”—leading scientists and business and social entrepreneurs around the world. Among the most frequently cited are Francisco Varela, the Chilean-born biologist, cognitive scientist, and practicing Buddhist who developed groundbreaking theories about the nature of life and living systems before his untimely death in 2000 (Presence is dedicated to him), and Brian Arthur, Santa Fe Institute economist, complexity theorist, and practicing Taoist.

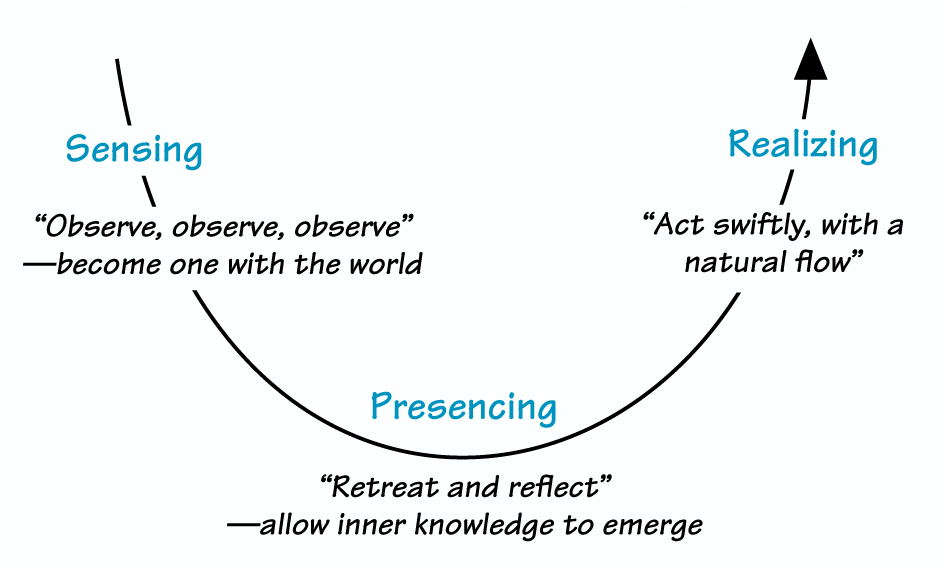

The theoretical skeleton, developed by Scharmer from the interview material, is called “Theory of the U.” It proposes a three-stage model for deep change, with the letter U serving as a simple and elegant visual device (see “The U Process”). The lefthand, downward stroke of the U is called “sensing,” the turn at the bottom is “presencing,” and the upward stroke is “realizing.” The authors make the point that these three stages are not in themselves so different from standard models of learning and innovation that involve a progression from observation and data-gathering to reflection to action. What is different, and crucial, is the depth of experiencing achieved in the U process. In other words, a conventional observe-reflect-act model is a sort of shallow U. It may produce innovation, but only within the same frame of reference from which it began. The standard model “pays little attention to the inner state of the decision maker.” It does not challenge and remake the identity of the change agents themselves.

THE U PROCESS

Reprinted from Presence, with permission

To arrive at the deeper experience of presencing, we must first cultivate a deeper kind of observation, called “sensing.” This involves a specific set of experiential capacities that, though innate, must be developed. Based in the work of Varela, these subtle internal gestures are called “suspending,”, “redirecting,” and “letting go.” Roughly speaking, “suspending” is the ability to pause one’s habitual flow of ideation and mental models built up in the past, in the service of opening up a space of consciousness that is free from already-formed concepts.

“Redirecting,” also described as the ability to “see from the whole to the part,” is especially subtle and crucial. It is essentially a psycho-spiritual capacity to dissolve the boundaries between seer and seen, subject and object. “What first appeared as fixed or even rigid begins to appear more dynamic because we are sensing the reality as it is being created, and we sense our part in creating it. This shift is challenging to explain in the abstract but real and powerful when it occurs.”

The third gesture, “letting go,” is the capacity to “surrender our perceived need to control.” It is the antidote to fixed views and attachments, self-concepts, and even ideas that form during the process of innovation. The gesture of letting go brings us back to the present moment, the here and now, as both concrete reality and an endless open field of fresh possibility.

The bottom of the U is “presencing,” the mysterious, transformative moment of “field shift”—a deeply felt paradigm shift in which participants’ sense of who they are alters in synchronicity with the arising of new, previously unimaginable options for action. The authors give dramatic examples of this moment, drawn from both individual and group experiences. The two most powerful examples of collective presencing are from conflict-mediation situations. In one, a meeting among black and white South Africans during the Apartheid era leads to a stunning, in-the-moment realization by a taciturn Afrikaans businessman of the deep racial prejudices ingrained in him from childhood. His anguished but genuine confession generates an extraordinary collective experience of pain, mutual recognition, and breakthrough. In the second instance, an eyewitness account of a mass grave site from the Guatemalan civil war produces one shocking detail that dissolves the conceptual and emotional barriers among a group of former enemies. A long and pregnant silence ensues, in which a deep commonality is recognized and a commitment to building a life-affirming future for the country is born.

The final movement of the U is “realizing,” a three-stage process of operationalizing the radical learning achieved in “sensing” and “presencing.” A key injunction here is that, after the slowing down and deepening of the earlier stages, realizing must be executed with swiftness and courage. Given that many of our organizational situations do not lend themselves to abrupt change, how is this possible? The authors recommend “rapid prototyping”— quickly enacting innovative ideas as small-scale, real-world experiments. They make the point that, in prototyping, you construct and test a model before you understand the whole of the emergent situation. It is only through a rapid cycle of experiments involving the “capacity for self-observation and course correction in real-time” that a sustainable new operational design can emerge. “Prototyping is not about abstract ideas or plans but about entering a flow of improvisation and dialogue in which the particulars inspire the evolution of the whole and vice versa.”

The end point of the U comes when innovation is institutionalized. Scharmer says, “[Institutionalizing] can sound like making something that is rigid and fixed. I think of it as more like the collective equivalent of embodying—we know we’ve learned something when it becomes part of how we do things. Until the new becomes embedded in its own routines, practices, and institutional laws, it’s not yet real.”

As an example of this kind of institutionalizing, and of the whole U process successfully carried through to unforeseen and powerful results, the authors describe the creation of Visa in the late 1960s and early 1970s under the leadership of Dee Hock. Visa is now one of the largest businesses in the world, but rather than being publicly traded, it is owned by its 22,000 member institutions, which are simultaneously one another’s suppliers, customers, and competitors. Its groundbreaking network design—Visa operates as a worldwide democracy governed by a common purpose and set of principles but with an unfettered capacity to grow and change in response to local conditions—emerged through a multi-year process of dialogue among key players in the industry. “Visa was born out of deep immersion in the chaos of the early days of the credit card industry. That chaos ultimately gave way to a sense of the unique opportunity that was available—if people could suspend their established assumptions about banking, set aside their self-interest, and truly see what was needed to serve an emergent whole.” The ultimate breakthrough came about when Hock and his colleagues were able to imagine a business model patterned after a complex living system built up from genetic code.

Senge emphasizes that both the process of reinventing the credit-card industry and the innovative solution arrived at were democratic processes, as opposed to the “totalitarian dictatorships” that still function in most of our institutions. He makes a powerful plea for true democracy within organizations:, “[T]his is the defining feature of our era regarding leadership. In a world of global institutional networks, we face issues for which hierarchical leadership is inherently inadequate.”

Our Own Sources of Power

For deep organizational and societal change to occur, there must be an ongoing synergy between the personal and the collective.

In the end, Presence returns to a theme first articulated in The Fifth Discipline, that the capacity to do all of this depends on personal mastery, and specifically on the cultivation of reflective awareness. The authors cite Buddhist meditation and other Eastern contemplative practices as powerful methods for this cultivation. Senge, who speaks from his own deep commitment to study and daily meditation under the direction of a remarkable Chinese Zen-Taoist-Confucian master, uses a simple systems diagram to illustrate the pervasive dysfunction lying at the heart of modern culture. He says: “Western culture’s growing reliance on reductionist science and technology over the past 200 years fits the shifting-the-burden-dynamic remarkably well, revealing a play of forces that create growing technological power and diminishing human development and wisdom. . . . By giving us perceived power, modern technology reduces the felt need to cultivate our own sources of power.”

For deep organizational and societal change to occur, there must be an ongoing synergy between the personal and the collective. Generating new options depends both on the inner development of individuals and on collective processes in which they mutually enact the field of the emergent future. Presence concludes on a hopeful note that contains a call to inquiry and to action. “The changes in which we will be called upon to participate in the future will be both deeply personal and inherently systemic. The deeper dimensions of transformational change represent a largely unexplored territory both in current management research and in our understanding of leadership in general.” Auspiciously, this book serves as a personal and collective compass to guide us into this new land.

David I. Rome is senior vice president for planning at the Greyston Foundation, an integrated system of nonprofit and for-profit organizations in Yonkers, New York, that offers a wide array of programs and services to more than 1,200 men, women, and children annually. He also presents “Deep Listening,” a training program in reflective awareness and communication skills. David and his colleagues from Greyston will be presenting at the 2004 Pegasus Conference.